1951 Pacific typhoon season

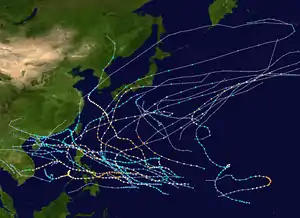

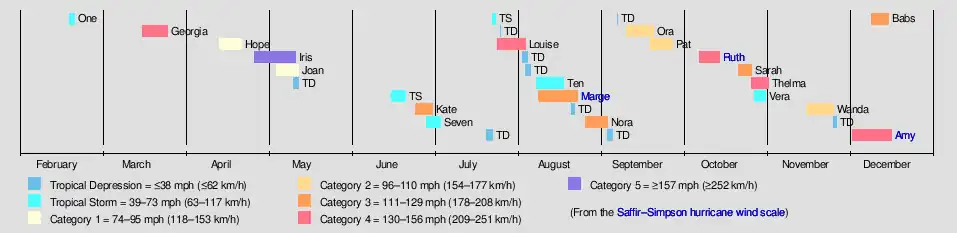

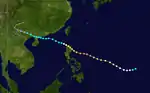

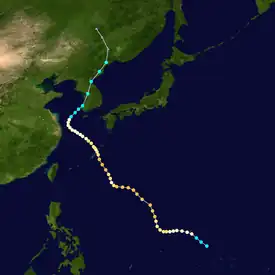

The 1951 Pacific typhoon season was a generally average season with multiple tropical cyclones striking the Philippines. With the exception of January, each month saw at least one tropical system develop; October was the most active month with four tropical cyclones forming. Overall, there were 31 tropical depressions, of which 25 became tropical storms; of those, there were 16 typhoons.

| 1951 Pacific typhoon season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | February 19, 1951 |

| Last system dissipated | December 16, 1951 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Marge |

| • Maximum winds | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 886 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 31 |

| Total storms | 25 |

| Typhoons | 16 |

| Super typhoons | 1 (unofficial) |

| Total fatalities | 1,185 total (including missing and injured) |

| Total damage | $106.15 million (1951 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The season began with the formation of a short-lived unnamed tropical storm on February 19, well east of the Philippines; Typhoon Georgia became the season's first named storm and typhoon after first developing in the open Pacific on March 20. In April, Typhoon Iris developed before intensifying into a super typhoon the following month; Iris was the first recorded instance of a Category 5-equivalent typhoon in the western Pacific. The final typhoon and storm of the year was Typhoon Babs, which remained at sea before dissipating on December 17.

The scope of this article is limited to the Pacific Ocean, north of the equator and west of the International Date Line. Storms that form east of the date line and north of the equator are called hurricanes; see 1951 Pacific hurricane season. At the time, tropical storms that formed within this region of the western Pacific were named and identified by the Fleet Weather Center in Guam. However, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), which was established five years later, identified four additional tropical cyclones during the season not tracked by the Fleet Weather Center; these analyzed systems did not receive names.

Systems

Typhoon Georgia

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 18 – March 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

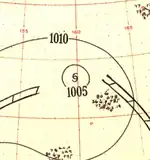

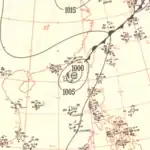

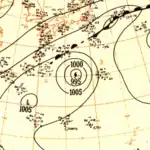

A persistent low-pressure area south of Kusaie was first noted on March 14. The origins of the cyclonic circulation remain disputed, with one hypothesis indicating initial development south of Nauru and another suggesting that the system originated from a minor tropical wave east of the Marshall Islands. Nonetheless, southeasterly flow associated with an unusually strong high pressure area positioned over northeastern Australia aided the tropical cyclogenesis of the disturbance,[1] and at 1200 UTC on March 18, the circulation developed into a tropical depression. In its initial stages, the disturbance steadily intensified as it moved in a northeasterly direction, attaining tropical storm strength by 1800 UTC the next day. At 0600 UTC on March 20, Georgia reached typhoon intensity;[2] however, the Guam Fleet Warning Center only issued its first typhoon bulletin on the tropical cyclone at 0600 UTC the following day,[1] by which time Georgia already had winds of 185 km/h (115 mph), equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[2] At the same time, the typhoon began to develop an eye.[1] Subsequently, Georgia attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 220 km/h (140 mph), equivalent to a modern-day Category 4 hurricane. Afterwards, the intense typhoon began to quickly lose organization and strength,[1] and degenerated into a remnant low after 0600 UTC on March 25,[2] coinciding with the last typhoon bulletin issued by the Guam Fleet Warning Center.[1] The remnants tracked westward before dissipating after 0600 UTC on March 28.[3]

As a developing tropical system, the precursor to Georgia and resultant tropical depression moved near Kusaie, producing a peak rainfall total of 137 mm (5.4 in) over a three-day period and gusts in excess of 95 km/h (59 mph). On March 20, Georgia passed to the south of Kwajalein. As such, the island's station observed "strong surface winds" and 236 mm (9.3 in) of rain in an eighteen-hour period.[1] As a weakening tropical cyclone, Georgia threatened Wake Island and Eniwetok Atoll; the latter of which was expected to be the site of American nuclear testing operations.[4] Though both islands were warned of by the Guam Fleet Weather Center, however, the typhoon had weakened considerably before reaching them, and effects remained marginal. Nonetheless, 52 mm (2.0 in) of rain was reported on a weather station in Eniwetok.[1] The nuclear testing operation, termed Operation George, remained unaffected,[5] though the first test was detonated on July 4, well after Georgia dissipated.[6]

Typhoon Hope

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 15 – April 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

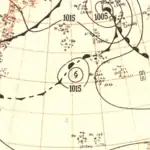

In early April, several cyclonic vortices were noted south of the Marshall Islands. One of these circulation centers tracked westward and later developed into a tropical depression near Micronesia early on April 15.[7][8] Steadily intensifying, the disturbance intensified into a tropical storm by 1800 UTC the next day. At roughly the same time, Hope began to curve slightly to the north. The Guam Fleet Warning Center estimated that the tropical storm intensified into a typhoon by 1800 UTC on April 17, before strengthening further to reach its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 130 km/h (81 mph) at 0000 UTC.[8] At the same time, the weather center at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam began issuing bulletins on the storm. Shortly after, Hope executed a small anticyclonic loop, which resulted in the tropical cyclone tracking westward. After this loop was completed, however, the typhoon began to weaken.[7] This weakening trend continued, and the Guam Fleet Warning Center ceased the issuance of bulletins at 1200 UTC on April 20, by which time Hope was deemed too weak to be classified as a tropical cyclone. However, the China Meteorological Agency (CMA), in analysis of the system, determined that Hope had persisted up until late on April 23 before dissipating.[8]

Typhoon Iris

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 28 – May 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 280 km/h (175 mph) (1-min); 909 hPa (mbar) |

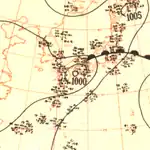

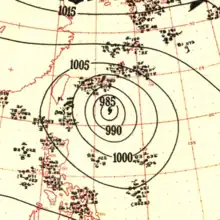

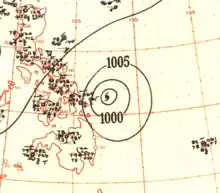

In late April, a well-developed tropical wave began developing east of Chuuk Lagoon.[9] Tracking westward, the easterly wave was analyzed to have organized into a tropical depression by 0000 UTC on April 29.[10] Twelve hours later, Iris was estimated to have strengthened into a tropical storm.[11] At roughly the same time, a vessel in the vicinity of the storm reported winds in excess of 65 km/h (40 mph), prompting the Guam Fleet Weather Center to initiate reconnaissance flights into the cyclone.[7] Midday on April 30, Iris intensified into the equivalent of a modern-day typhoon as it moved in a slightly oscillatory path towards the Philippines.[7][11] After a slight fluctuation in intensity during the overnight hours of May 1, Iris rapidly intensified to reach its peak intensity with a minimum pressure of 909 mbar (909 hPa; 26.8 inHg) and maximum sustained winds of 280 km/h (170 mph) early on May 4,[11] making it the equivalent of a Category 5 super typhoon;[10] at the time this was the first confirmed instance of a typhoon reaching such intensities.[2] Afterwards, Iris weakened slightly before making landfall on South Luzon around 1800 UTC the following day.[11]

After passing and weakening through the Philippines, Iris emerged into the South China Sea on May 6 as a tropical storm. At the same time, it began to recurve towards the northeast. On May 9, Iris reached a secondary peak intensity south of the Ryukyu Islands with winds of 160 km/h (99 mph), before subsequently weakening.[11] Afterwards, the tropical cyclone underwent extratropical transition, though the timing of such an event is disputed between the JMA and the CMA, with the former indicating that such a transition occurred on May 11,[12] and the latter indicating a transition on May 14.[10] Nonetheless, Iris made an anticyclonic loop beginning on May 11, before accelerating northeastward and dissipating entirely on May 15.[11] Upon its dissipation, Iris set Guam Fleet Weather Center records for number of tropical cyclone bulletins issued, at 50, and number of reconnaissance fixes, at 54.[7][11] At its landfall in the Philippines, the typhoon caused nine fatalities and injured an additional 39 people.[13] Rainfall peaked at 484.4 mm (19.07 in) in Gandara, Samar, with observed winds peaking at 155 km/h (96 mph) in nearby Catbalogan. Damage to highways, bridges, and crops was estimated at ₱19.2 million (US$9.5 million).[14]

Typhoon Joan

| Category 1 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 3 – May 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

A stationary trough of low pressure persisted near Nauru towards the end of April and into early May, producing heavy rains; a station on the island received 8.16 in (207 mm) in a 24-hour period from the system. An interaction between the trough and a passing tropical wave resulted in the formation of an organized disturbance on May 2 that tracked initially northwestward before taking a more westerly course. According to the JTWC, the system became sufficiently organized to be considered a tropical cyclone on May 3,[1] though the JMA indicates cyclogenesis three days later.[15] After some fluctuations in its strength in its nascent stages, Joan curved towards the northeast and strengthened into a typhoon on May 8, peaking that day with winds of 140 km/h (87 mph) and a minimum pressure of 980 mbar (980 hPa; 29 inHg). Concurrently, the typhoon stalled and traced out a clockwise loop for roughly a day before resuming a course towards the northwest. Gradual weakening ensued, and the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone after May 12; the system would dissipate three days later.[1]

Typhoon Kate

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 26 – July 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 975 hPa (mbar) |

A disturbance was first noted in the vicinity of Micronesia on June 17 approximately 400 km (250 mi) south of Guam. Aircraft traversing between Guam and the Philippines eventually confirmed the presence of a developing tropical depression by June 25, tracking towards the west.[7] By the following day, the system had strengthened into a tropical storm. The system curved towards the north by June 28 and had begun to trend towards the northeast thereafter, gradually strengthening to a typhoon by 18:00 UTC that day. The storm continued to accelerate towards the northeast, passing just east of the Ryukyu Islands on June 30 before reaching peak intensity offshore Kyushu with maximum sustained winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) and a central pressure estimated at 975 mbar (975 hPa; 28.8 inHg). Kate weakened slightly before making landfall the following day on Shikoku with winds of 170 km/h (110 mph).[16] The typhoon curved eastward and continued to weaken, tracking through Sagami Bay and emerging over the Pacific Ocean on July 2 as a tropical storm.[7][16] Kate transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and would later dissipate the following day.[17]

Thirteen people died on Kyushu. Heavy rains flooded 2,000 houses and inundated 8,000 acres of farmland in Kagoshima and Miyazaki prefectures.[18]

Typhoon Louise

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 26 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 904 hPa (mbar) |

The westerly-tracking tropical wave that would develop into Typhoon Louise was closely monitored as it passed Guam on July 25. Strong winds and falling pressures documented in Ulithi strongly suggested that a tropical cyclone was developing in the vicinity.[7] The CMA analyzed the system promptly developing as a strong tropical storm early on July 25;[19] however, the JTWC would not begin issuing bulletins on Louise until reconnaissance aircraft confirmed the presence of an already stout typhoon the following day with winds of 145 km/h (90 mph). Tracking towards the west-northwest, the storm steadily strengthened, reaching its peak intensity on July 29 east of Luzon with winds peaking at 220 km/h (140 mph) and the central pressure bottoming out at 904 mbar (904 hPa; 26.7 inHg). Typhoon-strength winds began to rake the Filipino province of Isabela that day, ahead of Louise's eventual landfall on July 30 with winds of 185 km/h (115 mph).[7] The mountainous terrain weakened the storm significantly,[20] and Louise remained weakened system as it traversed the South China Sea before tracking over Wuchuan, Guangdong as a minimal tropical storm on August 2. The tropical cyclone degenerated into a remnant low inland the following day before dissipating entirely on August 5.[19]

Communications were cut in Cagayan on the northeastern portions of Luzon as strong winds felled antennas.[21][22] In Tuguegarao, 300 homes were blown down by winds estimated at 145& km/h (90 mph), with similar destruction wrought to homes on the coastal city of Vigan.[20] The typhoon brought copious amounts of rainfall to Luzon, peaking at 483 mm (19.0 in) in a 24-hour period in Baguio; this total nearly set an all-time daily rainfall record for the city.[23] There were six fatalities and ten people were injured.[24][25] Damage was estimated at ₱5.5 million (US$2.7 million).[26]

Typhoon Marge

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 10 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 886 hPa (mbar) |

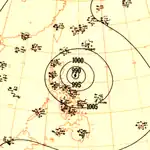

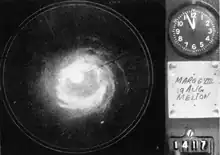

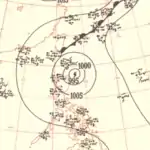

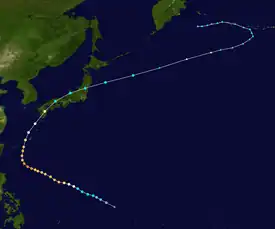

Typhoon Marge originated as a tropical storm southeast of Guam on August 10. Tracking towards the northwest, the strengthening system passed just south of the island the following day as a typhoon. On August 13, the storm began taking a more northwesterly path as it continued to intensify, reaching its peak intensity two days with maximum winds estimated at 185 km/h (115 mph) and a remarkably low pressure of 886 mbar (886 hPa; 26.2 inHg). Fluctuating in strength over the following days, Marge passed over the Amami Islands on August 18 before a more steadily weakening trend took hold as the typhoon moved into the East China Sea. The storm passed just offshore Shanghai before curving sharply towards the northeast into the Yellow Sea on August 21. Marge weakened to a tropical storm the next day after spending 11 continuous days as a typhoon. The cyclone made landfall near Boryeong, South Korea on August 23 and accelerated northeastwards across the Korean peninsula, transitioning into an extratropical cyclone over far-northeastern Manchuria before dissipating after August 24.[27]

Marge was the largest tropical cyclone ever observed to date, with a wind circulation extending 1,160 km (720 mi) in diameter; this record stood until it was eclipsed by Typhoon Tip in 1979.[28] Meteorologist Robert Simpson flew on board a reconnaissance mission that flew into Marge near its peak strength and documented the eye's visual and sampled characteristics. The flight was an atypical departure from normal reconnaissance missions due to secondary—albeit procedurally constrained—storm-research objectives.[29] Publishing his findings in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society in 1952, his work would be instrumental in the understanding of tropical cyclone structure.[30]

United Nations naval vessels and United States Navy armaments responding to the Korean War were evacuated from the western coast of the Korean peninsula in advance of the approaching typhoon.[31][32] Gusts as high as 180 km/h (110 mph) were reported in Okinawa in what was considered the island's most impactful typhoon since U.S. military occupation in 1945.[33] Although damage was minimal to U.S. military installations,[34] crop damage was extensive in other parts of Okinawa and several roads and highways were washed out by the heavy rains and surf. Impacts were more extensive further north of Kyushu, where rainfall totals as high as 400 mm (16 in) produced widespread flooding that flooded rice paddies and over a thousand homes, prompting the evacuation of 11,943 people. Offshore, twelve fishing boats capsized in the rough surf, and storm surge killed four in the Kyushu village of Yoshikawa.[35] Across southern Japan, there were 12 deaths and 53 injuries caused by Marge.[36] In South Korea, the Busan area was particularly hard hit, with coastal flooding displacing 550 people from their destroyed wooden homes. A half-mile segment of railroad between Yeosu and Daejeon was also washed out.[37]

Typhoon Nora

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 27 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

Nora produced "some damage" over a sparsely populated region of northern Luzon and caused communications outages.[38] In Hainan, 800 homes were destroyed along with 53 fishing boats. Two people were killed and fifteen were injured in Haikou.[39]

Typhoon Ora

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 11 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Ora struck China

Typhoon Pat

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 20 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Yap International Airport recorded 182.6 mm (7.19 in) of rain from Pat.[40]

Typhoon Ruth

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 8 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 924 hPa (mbar) |

Storm warnings were issued for southern Japan on October 13.[41] Planes in Tokyo were grounded and courier service to Korea was suspended.[42] Ruth impacted Japan between October 13–15, killing 572 people and injuring another 2,644; 371 people were left unaccounted for.[43] Many of these deaths arose from river flooding triggered Ruth.[44] The storm damaged 221,118 homes and 9,596 ships, as well as some 3.5 million bushels of rice.[43] Due to Ruth's large size, much of the country was affected by the typhoon's winds and rains. A peak wind gust of 195 km/h (121 mph) and a rainfall total of 639.3 mm (25.17 in) was recorded Kamiyaku, Kagoshima; both of these values were the highest recorded in Japan from Ruth.[44] Yamaguchi Prefecture was most severely impacted by the typhoon.[43][45] Coastal areas were inundated and communications were disrupted.[46] Winds reaching 150 km/h (93 mph) and waves 13.5 m (44 ft) high struck Sasebo, Nagasaki, sinking ships and damaging others in the harbor; among them were warships deployed for the Korean War.[47] American military installations throughout Japan incurred over US$1 million in damage.[48] Overall property damage in Japan was estimated at US$25 million, affecting an estimated 123,773 people;[49] total damage to property, crops, and forests reached US$55 million.[50]

Typhoon Sarah

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 22 – October 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 960 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Sarah remained in open waters.

Typhoon Thelma

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 27 – November 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 230 km/h (145 mph) (1-min); 950 hPa (mbar) |

Thelma formed as a Tropical Storm on October 27 and strengthened to category 4 status with 145 mph winds. Thelma later curved away without affecting land at all before it dissipated on October 2. It did not affect land. It was one of the strongest of the season, however damage was minimal, and no deaths were reported.[51]

Tropical Storm Vera

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 28 – November 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Vera remained at Tropical Storm status and did not affect land at all, thus being a minimal storm.

Typhoon Wanda

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 16 – November 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 985 hPa (mbar) |

On November 21, Typhoon Wanda moved across the Visayas and southern Luzon. The storm impacts fatally injured 82 people and displaced 213,242 others from their homes.[52]

Typhoon Amy

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 3 – December 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 950 hPa (mbar) |

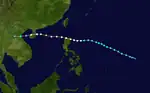

On December 3, an area of low pressure first noted near the Kwajalein Atoll developed into a tropical cyclone. Tracking in a general westward direction, the storm quickly intensified to reach typhoon intensity the next day. However, the typhoon's asymmetricity resulted in a fluctuation of intensity over the following few days.[7][53] Afterwards, Amy was able to intensify to reach its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 220 km/h (140 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 950 mbar (950 hPa; 28 inHg) on December 8. Over the ensuing two days, Amy moved over several islands in the central Philippines before emerging in the South China Sea on December 11 as the equivalent of a minimal typhoon. Shortly after, the tropical cyclone executed a tight anticyclonic loop while oscillating in strength several times before eventually weakening and dissipating on December 17,[7][53] just east of Vietnam.[53]

In the Philippines, Amy was considered one of the worst typhoons to strike the island chain on record.[54] Making its initial landfall along with the concurrent eruption of Mount Hibok-Hibok on Camiguin, the typhoon disrupted volcanic relief operations and forced the displacement of victims already displaced by the volcano.[55][56] Cebu City suffered the worst impacts of Amy – most of the city's buildings were heavily damaged, and 29 people died in the city.[57][58] Strong winds and rainfall in the city associated with Amy also set records which still remain unbroken today.[59] Damage there was estimated at ₱560 million.[60] Along the east coast of Leyte, where Amy initially struck, ninety percent of homes were destroyed,[61] and a large swath of coconut plantations were wiped out.[62] In Panay, located on the western side of the Philippines, at least a thousand homes were destroyed in 41 towns.[63] Overall, Amy caused $30 million in damage,[64][65] and at least 556 fatalities,[66] though the final death toll may have been as high as 991, making the typhoon one of the deadliest in modern Philippine history.[54] An additional 50,000 people were displaced by the storm.[64]

Typhoon Babs

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 10 – December 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Babs stayed at sea and caused no damage.

Unnamed systems

In addition to the 17 named storms monitored by the JTWC throughout the year, 14 other cyclones were analyzed by various agencies across East Asia, some of which were estimated to have reached tropical storm strength. Furthermore, disagreement on the intensity of these storms exists between the warnings centers. The table below lists the maximum intensity reported by any one agency for the sake of completeness. However, any tropical storms listed here are not considered official and thus are excluded from the season total.

| Agency/Agencies | Dates active | Peak classification | Sustained windspeeds (10-minute sustained) |

Pressure | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JMA | February 19 – 21 | Tropical storm | N/A | 990 mbar (990 hPa; 29 inHg) | [67] |

| CMA | May 12 – 13 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 998 mbar (998 hPa; 29.5 inHg) | |

| CMA | June 17 – 22 | Tropical storm | 75 km/h (47 mph) | 992 mbar (992 hPa; 29.3 inHg) | |

| CMA, JMA | July 1 – 9 | Tropical storm | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 992 mbar (992 hPa; 29.3 inHg) | |

| CMA | July 22 – 24 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 1,002 mbar (1,002 hPa; 29.6 inHg) | |

| CMA, JMA | July 22 – 26 | Tropical storm | N/A | 1,005 mbar (1,005 hPa; 29.7 inHg) | |

| CMA | July 27 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (28 mph) | 1,006 mbar (1,006 hPa; 29.7 inHg) | |

| CMA | August 4 – 6 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 1,002 mbar (1,002 hPa; 29.6 inHg) | |

| CMA | August 5 – 7 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 995 mbar (995 hPa; 29.4 inHg) | |

| CMA, JMA | August 9 – 19 | Tropical storm | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 989 mbar (989 hPa; 29.2 inHg) | |

| CMA | August 22 – 23 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 1,005 mbar (1,005 hPa; 29.7 inHg) | |

| CMA | September 4 – 6 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 995 mbar (995 hPa; 29.4 inHg) | |

| CMA | September 8 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (34 mph) | 1,000 mbar (1,000 hPa; 30 inHg) | |

| CMA | November 26 – 27 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (28 mph) | 1,004 mbar (1,004 hPa; 29.6 inHg) | |

Season effects

The following table lists all of the tropical cyclones that formed during the 1951 Pacific typhoon season, including their names, duration, intensities, damages, and death totals. Damage and deaths include totals for storms before tropical cyclogenesis and after extratropical transition. The duration of storms is based on data provided from the China Meteorological Administration, while maximum sustained wind data is provided by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Pressure data is provided by the Japan Meteorological Agency.

| Name | Dates | Peak intensity | Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Wind speed | Pressure | ||||||

| Georgia | March 18 – 25 | Category 4 typhoon | 220 km/h (140 mph) | 970 hPa (28.67 inHg) | Marshall Islands, Wake Island | Minimal | None | [1] |

| Hope | April 15 – 23 | Category 1 typhoon | 130 km/h (81 mph) | 980 hPa (28.94 inHg) | None affected | None | None | [8] |

| Iris | April 29 – May 13 | Category 5 super typhoon | 280 km/h (170 mph) | 910 hPa (26.88 inHg) | Philippines | $9.5 million | 13 | [13] |

| Joan | May 3 – May 12 | Category 1 typhoon | 140 km/h (87 mph) | 980 hPa (28.93 inHg) | Nauru | None | None | [1] |

| Kate | June 26 – July 2 | Category 3 typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 980 hPa (28.79 inHg) | Japan | Unknown | 13 | [18] |

| Amy | December 3 – 17 | Category 4 typhoon | 220 km/h (140 mph) | 950 hPa (28.05 inHg) | Philippines | $30 million | 569 – 991 | [54][64][65][66] |

| Season aggregates | ||||||||

| 21 systems | February 18 – December 16 | 280 km/h (170 mph) | 886 mbar (886 hPa; 26.2 inHg) | |||||

See also

- Pacific typhoon climatology

- 1951 Pacific hurricane season

- 1951 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1950s South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons

- 1950s Australian region cyclone seasons

- 1950s South Pacific cyclone seasons

References

- Pate, Elbert W.; Taylor, George F. (September 1951). Operation Greenhouse (Technical Meteorological Report). Defense Technical Information Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "IrBTRACS For the Northern Hemisphere" (FTP). International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Digital Typhoon (March 19, 2013). "Typhoon 195102 (GEORGIA)". Digital Typhoon Detailed Track Information. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Typhoon Heading For Atomic Blast Testing Grounds At Eniwetok". Schenectady Gazette. Vol. 57, no. 149. Schenectady, New York. Associated Press. March 22, 2013. pp. 1, 10. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Typhoon Blows Itself Out In Eniwetok Area". The Telegraph-Herald. Vol. 115, no. 72. Dubuque, Iowa. Associated Press. March 25, 2013. p. 23. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Operation Greenhouse - 1951". SonicBomb. September 15, 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Air Weather Service; Military Air Transport Service; United States Air Force (September 1951). 1951 Annual Report Of Typhoon Post-Analysis Program (PDF) (Air Weather Service Technical Report). Washington, D.C.: Defense Technical Information Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "1951 02W:HOPE (1951105N08152)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Climatological Division of the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (August 25, 2010). Tropical Cyclones. Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration.

- China Meteorological Administration. "China Meteorological Administration Best Track Data For the 1951 Pacific Typhoon Season". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "1951 03W:IRIS (1951119N06145)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Digital Typhoon (March 19, 2013). "Typhoon 195104 (IRIS)". Digital Typhoon Detailed Track Information. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "Typhoon Takes South Luzon Toll". New York Times. Manila, Philippines. IMP. May 6, 1951. Retrieved 20 July 2013. (subscription required)

- Hernandez, Pedro P.; Koh, Severino L. (1951). "Tropical Cylones of 1951". Manila, Philippines: Philippines Weather Bureau Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "1951 04W:JOAN (1951124N04167)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "1951 05W:KATE (1951177N12136)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Digital Typhoon (June 1, 1981). "Typhoon 195106 (KATE)". Digital Typhoon Detailed Track Information. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Typhoon Kills 13 On Nippon Island". Democrat and Chronicle. Vol. 119. Rochester, New York. Associated Press. July 2, 1951. p. 4. Retrieved December 21, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1951 06W:LOUISE (1951206N11145)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- "10 Killed, Much Damage Caused by Luzon Typhoon". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Vol. 58, no. 18368. Honolulu, Hawwaii. Associated Press. August 1, 1951. p. 16. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "150-MPH Typhoon Rips Area In Philippines". Journal Herald. Vol. 144, no. 181. Dayton, Ohio. Associated Press. July 30, 1951. p. 8. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Philippine Typhoon Roars Into China Sea". The Battle Creek Enquirer and News. Vol. 52. Battle Creek, Michigan. Associated Press. July 30, 1951. p. 4. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Luzon Typhoon". The Rapid City Daily Journal. Rapid City, South Dakota. Associated Press. July 31, 1951. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "19 Inches of Rain in Luzon Typhoon". Wilkes-Barre Times Leader. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. July 31, 1951. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Typhoon Toll Hits 6". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 38, no. 64. Austin, Texas. Associated Press. August 2, 1951. p. 11. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Henderson, Faye (1979). Tropical Cyclone Disasters in the Philippines (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "1951 07W:MARGE (1951223N11148)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- National Summary (Report). Climatological Data. Vol. 30. Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 1979. p. 96 – via Google Books.

- Simpson, Robert H. (September 1952). "Exploring Eye of Typhoon "Marge," 1951". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 33 (7): 286–298. doi:10.1175/1520-0477-33.7.286.

- "65th Anniversary of Typhoon Marge flight". Hurricane Research Division. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 15, 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Approaching Typhoon Forces U.N. Ships Off Korea to Move". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Vol. 103, no. 330. St. Louis, Missouri. Associated Press. August 17, 1951. p. 6A. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Pacific Typhoon". The Leader-Post. Vol. 47, no. 194. Regina, Saskatchewan. Reuters. August 18, 1951. p. 5. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Okinawa Rides Out Typhoon". Muncie Evening Press. Vol. 59, no. 167. Muncie, Indiana. International News Service. August 21, 1951. p. 7. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Sweeps China Sea". Windsor Daily Star. Vol. 66, no. 144. Windsor, Manitoba. United Press. August 18, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Typhoon Skirts Japan; Six Dead". St. Petersburg Times. Vol. 68, no. 27. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. August 20, 1951. p. 17. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Heavy Loss In Typhoon". Mt. Pleasant News. Vol. 76, no. 195. Mt. Pleasant, Iowa. International News Service. August 19, 1951. p. 2. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Typhoon Hits Korea, Destroys Pusan Homes". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. Reuters. August 24, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Luzon Storm Swept". The Palm Beach Post. Vol. 43, no. 175. West Palm Beach, Florida. Associated Press. September 3, 1951. p. 6. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Typhoon Hits Hainan". Vancouver Sun. Vol. 45, no. 272. Vancouver, British Columbia. Reuters. September 3, 1951. p. 7. Retrieved December 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roth, David M. (June 15, 2020). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "Typhoon 'Ruth' Swirls Toward Japan's Coast". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Reuters. October 14, 1951. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Winds Send Troopship Onto Jap Island Shoal". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. No. 257. Fort Worth, Texas. Associated Press. October 15, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kitamoto, Asanobu. "Typhoon 195115 (RUTH)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "ルース台風". 災害をもたらした気象事例 (in Japanese). Tokyo, Japan: Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Typhoon Damages Rice". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. No. 263. Fort Worth, Texas. Reuters. October 21, 1951. p. 12. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Typhoon Hits U.S. Troopship Aground Off Japanese Coast". The Scranton Tribune. Scranton, Pennsylvania. United Press. October 15, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Typhoon Ruth - 14-15 October 1951". Anzac Day Commemoration Committee. ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee (Queensland) Incorporated. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Transfer 500 From Wrecked Ship". The Mt. Pleasant News. Vol. 73, no. 243. Mount Pleasant, Iowa. International News Service. October 15, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Typhoon Blows Out Harmlessly". The Elwood Call-Leader. No. 245. Elwood, Indiana. International News Service. October 16, 1951. p. 6. Retrieved May 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Nearly 500 Die in Jap Typhoon". Visalia Times-Delta. No. 174. Visalia, California. Associated Press. October 17, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- http://atms.unca.edu/ibtracs/ibtracs_v03r09/browse-ibtracs/index.php?name=v03r09-1951300N13155%5B%5D

- Clarence Paul Oaminal (January 5, 2015). "The calamities of 1951 and the President's action". The Philippine Star. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- "1951 16W:AMY (1951337N09150)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. University of North Carolina-Asheville. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Alojado, Dominic (July 29, 2010). "The Twelve Worst Typhoons Of The Philippines (1947 –2009)". Typhoon2000.com. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "Philippines Threatened By Typhoon". The Victoria Advocate. Victoria, Texas. Associated Press. December 9, 1951. p. 1A. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Typhoon Kills 3, Volcano Erupts Again". The Victoria Advocate. Vol. 6, no. 186. Victoria, Texas. Associated Press. December 10, 1951. p. 2. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- White, Frank L. (December 13, 1951). "569 Perish in Typhoon". The Ludington Daily News. Vol. 62, no. 34. Ludington, Michigan. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "Philippine Typhoon Kills At Least 14". Nashua Telegraph. Vol. 83, no. 238. Nashua, New Hampshire. Associated Press. December 10, 1951. p. 8. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. "Cebu Port Study". Monterrey, California: Navy Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. "Most Disastrous Tropical Cyclones Affecting Cebu Province Selection By Year From 1948 –2012". Monterrey, California: Navy Research Laboratory. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "23 Killed, 200 Lost In Typhoon". Miami Daily News. Vol. 56, no. 313. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. December 11, 1951. p. 13A. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "Typhoon Causes Heavy Damage". The Spokesman-Review. Vol. 69, no. 211. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. December 11, 1951. p. 2. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "16 Known Dead From Typhoon In Philippines". The News and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina. Associated Press. December 11, 1951. p. 2A. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "Two Typhoons Menace Manila". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Vol. 27, no. 61. Sarasota, Florida. Associated Press. December 12, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "Typhoon Rips Philippines". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 25, no. 113. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. December 11, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database". Université catholique de Louvain.

- Digital Typhoon (October 17, 1990). "Typhoon 195101 (NO-NAME)". Digital Typhoon Detailed Track Information. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

External links

- Japan Meteorological Agency

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center Archived 2010-03-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- China Meteorological Agency

- National Weather Service Guam

- Hong Kong Observatory

- Macau Meteorological Geophysical Services

- Korea Meteorological Agency

- Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration

- Taiwan Central Weather Bureau

- Digital Typhoon - Typhoon Images and Information

- Typhoon2000 Philippine typhoon website