Typhoon Kim (1980)

Typhoon Kim, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Osang, was the second typhoon in a week to directly affect the Philippines during July 1980. Like Typhoon Joe, Kim formed from the near equatorial monsoon trough in the northwestern Pacific Ocean on July 19. The disturbance tracked quickly westward-northwest underneath a subtropical ridge, reaching tropical storm strength on the July 21 and typhoon strength on July 23. After developing an eye, Kim began to rapidly intensify, and during the afternoon of July 24, peaked in intensity as a super typhoon. Several hours later, Kim made landfall over the Philippines, but the storm had weakened considerably by this time. Throughout the Philippines, 40 people were killed, 2 via drownings, and 19,000 others were directly affected. A total of 12,000 homes were destroyed and 5,000 villages were flooded. Less than a week earlier, the same areas were affected by Joe; however, Kim was considered the more damaging of the two typhoons. Land interaction took its toll on Kim, and upon entering the South China Sea, the storm was down below typhoon intensity. Kim continued northwestward but its disrupted circulation prevented re-intensification, and it remained a tropical storm until hitting southern China July 27 to the northeast of Hong Kong, where only slight damage was reported. Later that day, Kim dissipated.

| Very strong typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

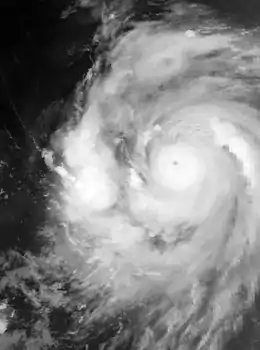

Kim during the late morning hours of July 24 | |

| Formed | July 19, 1980 |

| Dissipated | July 27, 1980 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 185 km/h (115 mph) 1-minute sustained: 240 km/h (150 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 910 hPa (mbar); 26.87 inHg |

| Fatalities | 41 total |

| Areas affected |

|

| Part of the 1980 Pacific typhoon season | |

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

An area of disturbed weather developed in association with the monsoon trough that was situated near the equator on July 19. At 20:04 UTC, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert for the system, primarily because the disturbance was over warm water and low wind shear.[1] Four hours later, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) classified the system as a tropical depression.[nb 1][3] Following reports from a Hurricane hunter plane of a well-defined surface circulation and winds of 40 to 50 km/h (25 to 30 mph), the JTWC classified the system as Tropical Depression 11 midday on July 20.[1] At the time, the depression was located over 600 km (375 mi) southeast of Guam.[4]

The depression tracked west-northwest, passing south of Guam and very near Ulithi around noon on July 21. Based on surface observations of 65 km/h (40 mph) on the island and data from Hurricane hunters, both the JTWC[1] and JMA upgraded the depression into a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC.[5] Post-storm analysis from the JTWC indicated that Kim attained tropical storm status six hours earlier,[6] despite aircraft data suggesting that the storm was not well stacked vertically. Further intensification was slow to occur as Kim tracked west-northwest, following Typhoon Joe across the Philippine Sea. At 06:00 UTC on July 23, a Hurricane hunter aircraft indicated falling pressures and the beginning of an eyewall.[1] Based on this, both the JTWC and JMA announced that Kim obtained typhoon intensity.[5] Around this time, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) also began to monitor the storm and assigned it with the local name Osang.[7] Continuing to track west-northwest beneath a large subtropical ridge,[1] Kim began to clear out an eye on the evening of July 23;[4] subsequently, Kim, as forecast by the JTWC, entered a period of rapid deepening.[1] At 06:00 UTC July 24, the JTWC increased the intensity of Kim to 185 km/h (115 mph), equal to a Category 3 hurricane on the United States-based Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS), while the JMA raised the winds to 170 km/h (105 mph).[5] Ten hours later, a Hurricane hunter aircraft measured a pressure of 908 mbar (26.81 inHg). This data justified the JTWC declaring Kim a super typhoon[1] and increasing the wind speed to 240 km/h (150 mph). At 18:00 on July 24, the JMA estimated that Kim reached its peak intensity to 170 km/h (105 mph) and assigned a pressure of 910 mbar (26.87 inHg).[5][nb 2]

Almost immediately thereafter, reports from the same Hurricane Hunter aircraft indicated that the pressure of the typhoon rose sharply, likely in response to decreased inflow caused by Kim's close proximity to land. The JTWC estimated that Kim made landfall along the coast of Luzon at an intensity of 185 km/h (115 mph),[1] while the JMA reported that Kim moved ashore with winds of 145 km/h (90 mph).[3] Continuing to weaken due to land interaction, Kim fell below typhoon intensity once it emerged into the South China Sea,[1] according to both the JTWC and JMA.[5] The JTWC expected Kim to revive over water in manner similar to Typhoon Joe, but this did not occur. The storm's inner core was disrupted by land, with Hurricane hunters constantly finding a poorly organized tropical cyclone. Kim began to move northwest in response to a weakness created in the subtropical ridge created by Joe. At 06:00 UTC on July 27, Kim crossed the coastline of China around 165 km (105 mi) northeast of Hong Kong.[1] At the time of its second landfall, both the JTWC and JMA estimated winds of 80 km/h (50 mph).[5] Twelve hours later, both the JTWC[6] and JMA ceased tracking Kim.[5]

Preparations and impact

Typhoon Kim caused widespread flooding across Luzon. In Manila, where floodwaters rose to more than 610 mm (24 in) in some suburbs, government offices and schools were closed. There, both Philippine Airlines and Philippine National Railways canceled all trips to the rest of the country.[9] The coast guard suspended sailing permits to ships throughout the country.[10] The Isabela province was the hardest hit by Typhoon Kim.[11] Almost 15 people were killed in the Cagayan province.[12] Across the Philippines, 40 people were killed,[13] 2 via drownings,[10] and 19,000 others were affected.[13] A total of 12,000 homes were destroyed and 5,000 villages were flooded.[4] Less than a week earlier, the same areas were affected by Typhoon Joe;[14][15] Kim was considered the more damaging of the two systems.[9]

The typhoon brought showers to much of southern China, extending as far north as Pratas Island, Taiwan (ROC). Wind gusts of 130 km/h (80 mph) were measured in the town of Shantou. In Hong Kong, a No 1. hurricane signal was issued on July 25. The next day, the signal was increased to a No 3. hurricane signal. All signals were dropped late on July 22, after Kim moved inland. A minimum pressure of 998.9 mbar (29.50 inHg) was recorded at the Hong Kong Royal Observatory (HKO) on July 27, around the time Kim made its closest approach to the city. On Waglan Island, a peak wind speed of 78 km/h (48 mph) was reported while a peak wind gust of 128 km/h (80 mph) occurred at Star Ferry. HKO observed 136.3 mm (5.37 in) of rain over a 72-hour period. Within the vicinity of Hong Kong, minor damage was reported and there were no injuries. Power was knocked out in the urban city of Kowloon. Some villages were flooded and two landslides occurred.[4]

See also

- Other typhoons named Kim

- Similar early season Philippine typhoons

Notes

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[2]

- Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10-minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1-minute winds.[8]

References

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1981). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1980 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1980–1989 (Report). Archived from the original (.TXT) on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Hong Kong Observatory (1981). "Part III – Tropical Cyclone Summaries". Meteorological Results: 1984 (PDF). Meteorological Results (Report). Hong Kong Observatory. pp. 22–24. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1980 Kim (1980201N08155). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Typhoon 11W Best Track (TXT) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. December 17, 2002. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Padua, Michael V. (November 6, 2008). PAGASA Tropical Cyclone Names 1963–1988 (TXT) (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Typhoon Kim Batters Islands With 115-Mile-An-Hour Winds". Associated Press. July 25, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Second Typhoon In Week Hits Philippines". Associated Press. July 25, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Storm Heads For Southern China". Associated Press. July 26, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Typhoon hits Philippines". The Globe and Mail. July 26, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Disaster History: Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900–Present (PDF) (Report). United States Agency for International Development. August 1993. p. 168. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004. Retrieved May 31, 2017.