Immigration policy of the United States

Federal policy oversees and regulates immigration to the United States and citizenship of the United States. The United States Congress has authority over immigration policy in the United States, and it delegates enforcement to the Department of Homeland Security. Historically, the United States went through a period of loose immigration policy in the early-19th century followed by a period of strict immigration policy in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Policy areas related to the immigration process include visa policy, asylum policy, and naturalization policy. Policy areas related to illegal immigration include deferral policy and removal policy.

| United States citizenship and immigration |

|---|

| Immigration |

| Citizenship |

| Agencies |

| Legislation |

| History |

| Relevant legislation |

|

|

Policy development

Article One of the United States Constitution directly empowers Congress to establish laws regarding naturalization. Supreme Court rulings such as Chae Chan Ping v. United States in 1889 and Fong Yue Ting v. United States in 1893 hold that the powers of Congress over foreign policy extend to legislation regarding immigration.[1] The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution grants birthright citizenship through the Citizenship Clause. Historically, immigration to the United States has been regulated through a series of Naturalization Acts and Immigration Acts.

Since 2003, the Department of Homeland Security has been responsible for carrying out immigration policy in the United States, and the department has three agencies that oversee immigration. Customs and Border Protection is responsible for border control. The Immigration and Customs Enforcement is responsible for law enforcement around national borders and enforcement of laws against illegal immigration. The Citizenship and Immigration Services are responsible for processing legal immigration and naturalization.[2] Other agencies involved in immigration policy include the Executive Office for Immigration Review in the Department of Justice and the Office of Refugee Resettlement in the Department of Health and Human Services.

History

18th century

The United States did not heavily legislate on immigration during the 18th and 19th centuries, resulting in a policy of open borders. Citizenship was restricted on the basis of race. Immigration and naturalization were typically legislated separately at this time, with no coordination between policy on the two issues.[3] The Naturalization Act of 1790 was the first federal law to govern the naturalization process in the United States; restricting naturalization to white immigrants.[4] Several additional Naturalization Acts modified the terms of naturalization in the 1790s and 1800s.

19th century

To protect the rights of recently freed slaves, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 guaranteed that all individuals born within the United States were automatically granted citizenship.[5] This right was written into the Constitution under the Citizenship Clause with the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. The naturalization process was expanded to include African Americans with the Naturalization Act of 1870, but immigration from China was explicitly banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. As people from more countries immigrated to the United States, courts were tasked with determining the racial origin of prospective citizens to determine eligibility.[3] In 1898, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Wong Kim Ark that birthright citizenship applied to the children of Chinese immigrants.[6]

20th century

The Naturalization Act of 1906 created the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization to organize immigration policy.[3] Immigration to the United States from Japan ended in 1907 following an informal agreement between the two countries, and immigration restrictions on East Asian countries were expanded through the Immigration Act of 1917 and the Immigration Act of 1924. Immigration from China would not be restored until the Magnuson Act was passed in 1943.

The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 established the first quota system to restrict the amount of immigrants from a given country.[7] The Immigration and Naturalization Service was created in 1933 by combining the Bureau of Immigration and the Bureau of Naturalization. The Nationality Act of 1940 was passed to create a unified code of United States naturalization law.[8] Following World War II, the War Brides Act allowed exemptions of immigration quotas for immediate relatives of American service-members.[9] The Luce–Celler Act of 1946 made immigrants from India and the Philippines eligible for citizenship, though it capped entry at 100 immigrants per country per year.[10] The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 was passed to create a unified code of United States immigration law, and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 repealed the quota system that was used to limit immigration from each country.[11][12]

The Vietnam War resulted in a significant increase of immigrants and refugees to the United States from Southeast Asia.[13] The Refugee Act was passed in 1980 to establish a legal framework for accepting refugees, and the American Homecoming Act gave preferential status to immigrant children of American service-members. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 provided a path to permanent residency to some undocumented immigrants but made it illegal for employers to hire undocumented immigrants.[14] Immigration was significantly reformed by the Immigration Act of 1990, which set a cap of 700,000 immigrants annually and changed the standards for immigration.[15] The IIRIRA was passed in 1996 to apply restrictions on undocumented immigrants.[16]

21st century

In 2001, the Supreme Court ruled that immigrants cannot be held indefinitely if no country will accept them for deportation in Zadvydas v. Davis.[17] Enforcement of immigration law was reformed following the September 11 attacks, shifting focus to national security. The Immigration and Nationalization Service was split into the Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Customs and Border Protection.[2] The Real ID Act of 2005 placed restrictions on individuals applying for asylum, and the Secure Fence Act of 2006 began the process of building a fence across the Mexico–United States border.

After the failure of the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013, no significant immigration reform legislation has been enacted into federal law. President Obama adopted the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals in 2012, which as of 2023 is prohibited from adding new recipients but has not been struck down or repealed by President Biden due to the Supreme Court decisions in United States v. Texas (2016) and Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California (2020).

Legal immigration

The United States immigration system is based on the Nationality Act of 1965 and the Immigration Act of 1990 (INA).[18] The Citizenship and Immigration Services are responsible for refining immigration applications and administering the immigration process.[18] The INA allows the United States to grant approximately 675,000 permanent immigrant visas each year.[19] In addition to the 675,000 permanent visas, the INA does not have a limit on the annual admission of U.S. citizens (e.g. spouses, parents, and children under 21 years of age).[19] Family relationships, employment ties, or humanitarian protection are main causes for immigrant seeking temporary or permanent U.S. residence.[20] Also, each year the President (currently Joe Biden) is required to address the congress and place an annual number of refugees to be admitted into the United States through the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program.[19] When a person legally migrates into the United States they obtain an immigrant visa and become a lawful permanent resident (LPR).[19]

Visa policy

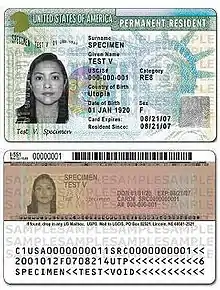

To seek entry to the United States, prospective immigrants must apply and be accepted for a travel visa. Immigrants seeking permanent residency are given a green card, which designates them as lawful permanent residents. Approximately one million green cards are granted annually. Between 2013 and 2017, 45% of green card recipients were immediate relatives of American citizens, and another 21% were family sponsored. 14% of recipients received green cards for employment, and 13% received green cards as refugees. The Diversity Immigrant Visa program also grants 55,000 green cards for applicants around the world each year. Immigrants seeking temporary residence in the United States apply for a temporary visa. Approved applicants are authorized to stay for a certain length of time, and they may also be authorized to work or attend university in the United States, depending on their visa category.[21]

Members of Congress may submit private bills granting residency to specific named individuals. A special committee vets the requests, which require extensive documentation. The Central Intelligence Agency has the statutory authority to admit up to one hundred people a year outside of normal immigration procedures, and to provide for their settlement and support. The program is called "PL110", named after the legislation that created the agency, Public Law 110, the Central Intelligence Agency Act.

Historically, laws such as the War Brides Act of 1945 was passed at the end of World War II and the American Homecoming Act of 1988 have been passed to allow immediate relatives of American service-members to immigrate to the United States following a major war. In 2013, the parole in place program was established to provide temporary residency for the immediate relatives of active duty military personnel while they applied for lawful permanent residency.[22] Children of military personnel born overseas are automatically granted American citizenship if their parents are American citizens. These children are processed through Conciliary Reports of Birth Abroad.

There are various nonimmigrant visa categories to seek entry into the United States for short periods of time and specific purposes. There are several requirements in order for someone to obtain a visa (e.g. visa fee, acceptable photograph, DS-160 visa application, required documents, visa interview appointment).[23] The four main types of visas are tourist, immigration, student, or work.[23] To obtain a tourist visa one needs to get visitor visa (B-12) unless one qualifies for the Visa Waiver Program.[23] International education is supported by the United States and welcomes foreign students and exchange visitors. To obtain a student visa, students need to admitted into their chosen schools or program sponsors.[23] A business visa requires a visitor visa (B-1) unless they qualify for the Visa Waiver Program.[23] Temporary workers must qualify for an available visa category based on their employment purpose.[23] Immigrants who want a permanent residency are granted a green card (immigrant visa), which allows for someone to work legally, travel abroad and return, bring children and spouse, and become eligible for citizenship.[24] About one million green cards are granted annually. In 2019, 13.7% of foreign-born residents populated the United States.[25]

Asylum policy

Asylum policy of the United States is governed by the Refugee Act of 1980. Under this law, the United States recognizes refugees as individuals with a "well-founded fear of persecution" in line with the definition established by the United Nations. It also established the Office of Refugee Resettlement within the Department of Health and Human Services to oversee asylum policy. The Refugee Act also provides a mechanism to raise the cap on annual refugee intake.[13]

Applying for refugee status is a separate process from applying for entry as an economic migrant, and refugees may apply from their home country or within their first year of entering the United States. Spouses and children of those seeking asylum are also considered in the application, and unaccompanied children can also apply independently. In order to qualify for asylum, applications must meet the legally recognized definition of a refugee, must have no record of serious crimes, and cannot have already been resettled in another country.[27]

After the Refugee Act was passed in 1980, the United States accepted 207,000 refugees in the first year.[28] In 2014, the number of asylum seekers accepted into the U.S. was about 120,000 compared to about 31,000 in the UK and 13,500 in Canada.[29] Asylum policy in the United States was more heavily regulated under the Trump administration, significantly reducing the number of refugees accepted to the United States and reducing resources toward asylum application processing, creating a significant backlog.[30] In 2021, the Biden administration raised the annual cap from President Trump's limit of 15,000 refugees to 62,500 with the intention of raising it to 125,000 the following year.[31] As of 2020, the backlog of asylum claims consists of more than 290,000 applicants.[32]

During the 1970s and 1980s, United States asylum policy focused on Southeastern Asia due to the Vietnam War. The United States increased the number of European refugees in 1989 by accepting Soviet refugees and in 1999 by accepting Kosovar refugees. During the 2000s, refugees primarily came from Somalia, Cuba, and Laos, with a significant increase in Burmese and Bhutanese refugees in 2008. As of 2016, refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, and Myanmar make up nearly half of all refugees entering the United States.[33]

Naturalization policy

Naturalization is the mechanism through which an immigrant becomes a citizen of the United States. Congress is directly empowered by the Constitution to legislate on naturalization. Naturalization in the United States is governed by the Immigration and Nationality Acts of 1952 and 1965, and it is overseen by the Citizenship and Immigration Services. To be eligible for naturalization, an applicant must be at least 18 years old, have established permanent residence for at least five years, have basic English proficiency, and have a basic knowledge of American civics. Applicants must also participate in an interview with the Citizenship and Immigration Services, to prove English proficiency and take the American Civics Test. 91% of applicants are successful in both the English and civics tests. Applicants that are granted naturalization take the Oath of Allegiance. During the 2010s, more than 7.3 million immigrants were naturalized. In 2020, Mexico, India, the Philippines, Cuba, and China were the most common countries of origin for immigrants.[34][35][36]

The Supreme Court has ruled that multiple citizenship is legal in Kawakita v. United States and Schneider v. Rusk.[37][38]

Illegal immigration

Illegal immigration is the act of an immigrant entering the United States without prior authorization. These undocumented immigrants are subject to removal from the United States. Policies regarding illegal immigration are primarily regulated by the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA). Immigration and Customs Enforcement is responsible for the prevention and investigation of illegal immigration. The Supreme Court ruled in 1982 that undocumented children are entitled to enrollment in public schools in Plyler v. Doe. Under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, undocumented immigrants are entitled to service from any hospital that accepts Medicare. Under the IRCA, it is illegal for employers to hire undocumented immigrants.

The illegal immigrant population of the United States is estimated to be between 11 and 12 million.[39] The population of unauthorized immigrants peaked in 2007 and has declined since that time.[39] The majority of the U.S. unauthorized immigrants are from Mexico, but "their numbers (and share of the total) have been declining" and as of 2016 Mexicans no longer make up a clear majority of unauthorized immigrants, as they did in the past.[40] Unauthorized immigrants made up about 5% of the total U.S. civilian labor force in 2014.[40] By the 2010s, an increasing share of U.S. unauthorized immigrants were long-term residents; in 2015, 66% of adult unauthorized residents had lived in the country for at least ten years, while only 14% had lived in the U.S. for less than five years.[40]

Amnesty provides lawful permanent residence or a path to citizenship to undocumented immigrants. In 1986, the IRCA authorized amnesty for undocumented immigrants that had resided in the United States since 1982. Approximately three million undocumented immigrants were granted amnesty under this law.[41] Amnesty programs have been found to have little overall effect on illegal immigration rates.[42]

Deferral policy

The United States has policies in place that provide for deferred action on removal of undocumented immigrants. When undocumented immigrants are placed under deferred action, the federal government does not take legal action against them for their immigration status and removal proceedings do not take place. The Reagan administration implemented the Family Fairness program in 1987. Following the passage of the IRCA, some undocumented immigrants were granted legal status, but their immediate relatives were not. The Family Fairness program granted deferment to some immediate relatives of immigrants that obtained legal status under the Immigration Reform and Control Act. The program was expanded in 1990, and it was codified into law later that year under the Immigration Act of 1990.[43]

The Obama administration implemented the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in 2012 to support undocumented immigrants that arrived in the United States as children. Under this program, eligible undocumented immigrants are granted a two-year deferral from removal and be authorized to legally work in the United States. The two-year period is also subject to renewal.[44][45] Eligibility requirements include being between the age of 15 and 31, having come to the United States before reaching the age of 16, having lived in the United States continuously for at least five years, and having any of the following: a high school diploma or GED, an honorable discharge from the military, or current enrollment as a student. Applicants are also limited by criminal records or other threats to public safety or national security.[46] Children of legal migrants do not qualify for DACA protection because they entered the country legally.[47] The Obama administration sought to implement a second deferral program, the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA), in 2014. Under this program, deferment would be granted to eligible undocumented immigrants that are the parents of American citizens or lawful permanent residents.[48] It was challenged in United States v. Texas and eventually rescinded by the Trump administration before it was implemented.[49][50]

Removal policy

Removal proceedings are governed by the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. The Executive Office for Immigration Review operates immigration courts, which oversee removal proceedings of immigrants. An immigration judge presides over removal proceedings, which determine whether an immigrant is subject to removal from the United States. Immigrants facing deportation are eligible to apply for cancellation of removal if they have established residence in the United States for at least 10 years, have not committed serious crimes, and provide for a lawful American resident.[51][52][53]

Most immigration proceedings are civil matters, though crimes committed to enter the United States, including fraud or evasion of border enforcement, are still subject to criminal charges. As immigration proceedings are civil matters, immigrants do not receive Sixth Amendment protections such as the right to counsel and the right to a jury trial, though Fifth Amendment protections have been found to apply.[54][55] As removal proceedings are conducted by an executive agency, they are under the jurisdiction of the executive branch rather than the judicial branch of government. The Attorney General has authority over immigration courts, and appeals are heard by the Board of Immigration Appeals.[55] Some have called for immigration courts to be moved to the judicial branch to prevent abuse by strengthening separation of powers.[56][57]

Whether people who are awaiting a decision on their deportation are detained or released to live in the United States in the meantime (possibly paying bail) is a matter of both law and discretion of the Justice Department. The policy has varied over time and differs for those with crimes (including entry outside an official checkpoint) versus civil infractions. The 2001 Supreme Court case Zadvydas v. Davis held that immigrants who cannot be deported because no country will accept them cannot be detained indefinitely. In some cases, immigrants may be subject to an expedited removal, resulting in removal without the involvement of an immigration court. Immigrants subject to removal proceedings may also withdraw an application or voluntarily depart.

References

- Greenawalt, Chloe (January 17, 2021). "The Source of the Federal Government's Power to Regulate Immigration and Asylum Law". Immigration and Human Rights Law Review. University of Cincinnati.

- Chishti, Muzaffar; Bolter, Jessica (2021-09-21). "Two Decades after 9/11, National Security Focus Still Dominates U.S. Immigration System". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- Smith, Marian L. (2002). "Race, Nationality, and Reality". Prologue Magazine. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 34 (2).

- Glass, Andrew (March 26, 2012). "U.S. enacts first immigration law, March 26, 1790". Politico. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "The Civil Rights Bill of 1866". US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act)".

- Knight, George S. (1940). "Nationality Act of 1940". American Bar Association Journal. 26: 12.

- Wolgin, Philip E.; Bloemraad, Irene (2010). ""Our Gratitude to Our Soldiers": Military Spouses, Family Re-Unification, and Postwar Immigration Reform". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 41 (1): 27–60. doi:10.1162/jinh.2010.41.1.27. ISSN 0022-1953. JSTOR 40785025. S2CID 144882116.

- Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 79–483: Luce–Celler Act of 1946

- "The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (The McCarran-Walter Act)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965". US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Refugee Act of 1980". National Archives Foundation. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 99–603: Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986

- Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 101–649: Immigration Act of 1990

- Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 104–208: Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (text) (PDF)

- "Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Immigration policy of the United States", Wikipedia, 2022-05-10, retrieved 2022-05-24

- "How the United States Immigration System Works". American Immigration Council. 2014-03-01. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Gelatt, Julia (2019-04-26). "Explainer: How the U.S. Legal Immigration System Works". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Gelatt, Julia (2019). "Explainer: How the U.S. Legal Immigration System Works". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "US Immigration Rules for Military Family Members". Military One Source. July 26, 2021. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- "Four Steps to Help You Apply for a Visa | Study in the States". studyinthestates.dhs.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- "Green Card Sponsorship - OU Human Resources". hr.ou.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- "Green Card Statistics". The American Dream. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- "First of 60,000 refugees from Bhutan arrive in U.S". CNN. March 25, 2008. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- "Questions and Answers: Asylum Eligibility and Applications". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. March 15, 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- Monin, Kira; Batalova, Jeanne; Lai, Tianjian (2021-05-12). "Refugees and Asylees in the United States". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Asylum Trends 2014" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Rupp, Kelsey (February 6, 2018). "New immigration policy leaves asylum seekers in the lurch". The Hill. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- "Statement by President Joe Biden on Refugee Admissions". The White House Briefing Room. 3 May 2021.

- Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021 (Report). U.S. Department of State. 2020.

- Igielnik, Ruth; Krogstad, Jens Manuel (February 3, 2017). "Where refugees to the U.S. come from". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Citizenship and Naturalization". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2020-07-05. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- "10 Steps to Naturalization". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2021-09-16. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- "Naturalization Statistics". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- "Kawakita v. United States, 343 U.S. 717 (1952)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- "Schneider v. Rusk, 377 U.S. 163 (1964)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- Sherman, Amy (July 28, 2015). "Donald Trump wrongly says the number of illegal immigrants is 30 million or higher". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016.

- Jens Manuel Krogstaf, Jeffrey S. PAssel & D'Vera Cohn, 5 facts about illegal immigration in the U.S. Archived April 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Pew Research Center (April 27, 2017).

- "1986: Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- Orrenius, Pia M.; Zavodny, Madeline (2003). "Do Amnesty Programs Reduce Undocumented Immigration? Evidence from IRCA". Demography. Duke University Press. 40 (3): 437–450. doi:10.2307/1515154. JSTOR 1515154. PMID 12962057.

- "Reagan-Bush Family Fairness: A Chronological History". American Immigration Council. December 9, 2014. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. April 12, 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- Faye Hipsman, Bárbara Gómez-Aguiñaga, & Randy Capps, Policy Brief: DACA at Four: Participation in the Deferred Action Program and Impacts on Recipients Archived May 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Migration Policy Institute (August 2016).

- Jeanne Batalova, Sarah Hooker & Randy Capps, DACA at the Two-Year Mark: A National and State Profile of Youth Eligible and Applying for Deferred Action Archived May 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Migration Policy Institute (August 2014), p. 3.

- Merelli, Annalisa (14 February 2018). "A contradiction in US policy is putting children of skilled professionals at risk of deportation".

- Randy Capps, Heather Koball, James D. Bachmeier, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, Jie Zong & Julia Gelatt, Deferred Action for Unauthorized Immigrant Parents: Analysis of DAPA's Potential Effects on Families and Children Archived April 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (February 2016), Migration Policy Institute.

- Adam Liptak & Michael D. Shear, Supreme Court Tie Blocks Obama Immigration Plan Archived June 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (June 23, 2016).

- State of Texas v. United States, 809 F.3d 134 (5th Cir. 2015).

- Gania, Edwin T. (2004). U.S. Immigration Step by Step. Sphinx. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-57248-387-3.

- Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 240A online Archived November 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Ivan Vasic, The Immigration Handbook (2008) p. 140

- Kate M. Manuel (March 17, 2016). "Aliens' Right to Counsel in Removal Proceedings: In Brief" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- "Immigration judge removed from cases after perceived criticism of Sessions". CNN. August 8, 2018.

- "Immigration Court Judges Are Skeptical of Jeff Sessions' Backlog-Busting Plan".

- Boston Globe editorial board (September 21, 2018). "Fire Jeff Sessions ... as the boss of immigration judges".

External links

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (PDF/details) as amended in the GPO Statute Compilations collection