Ulaid

Ulaid (Old Irish, pronounced [ˈuləðʲ]) or Ulaidh (Modern Irish, pronounced [ˈʊlˠiː, ˈʊlˠə]) was a Gaelic over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups.[1] Alternative names include Ulidia, which is the Latin form of Ulaid,[2][3][4] and in Cóiced, Irish for "the Fifth".[3][5] The king of Ulaid was called the rí Ulad or rí in Chóicid.[5][6][7]

Ulaid | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 450 – 1177 | |||||||||

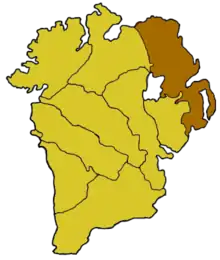

Map of Ireland's over-kingdoms circa 900 AD. | |||||||||

| Capital | Various | ||||||||

| Common languages | Irish | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• –465 | Forga mac Dallán | ||||||||

• 1172–1177 | Ruaidrí Mac Duinn Sléibe | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | Before 450 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1177 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Ulaid also refers to a people of early Ireland, and it is from them that the province of Ulster derives its name.[7] Some of the dynasties in the over-kingdom claimed descent from the Ulaid, but others are cited as being of Cruithin descent. In historical documents, the term Ulaid was used to refer to the population group of which the Dál Fiatach was the ruling dynasty.[7] As such, the title Rí Ulad held two meanings: over-king of the Kingdom of Ulaid and king of the Ulaid people, as in the Dál Fiatach.[5][7]

The Ulaid feature prominently in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. According to legend, the ancient territory of Ulaid spanned the whole of the modern province of Ulster, excluding County Cavan, but including County Louth.[1][2] Its southern border was said to stretch from the River Drowes in the west to the River Boyne in the east.[1][2][7] At the onset of the historic period of Irish history in the 6th century, the territory of Ulaid was largely confined to east of the River Bann, as it is said to have lost land to the Airgíalla and the Northern Uí Néill.[1] Ulaid ceased to exist after its conquest in the late 12th century by the Anglo-Norman knight John de Courcy, and was replaced with the Earldom of Ulster.[1]

An individual from Ulaid was known in Irish as an Ultach, the nominative plural being Ultaigh. This name lives on in the surname McAnulty or McNulty, from Mac an Ultaigh ("son of the Ulsterman").[8]

Name

Ulaid is a plural noun and originated as an ethnonym; however, Irish nomenclature followed a pattern where the names of population groups and apical ancestor figures became more and more associated with geographical areas even when the ruling dynasty had no links to that figure, and this was the case with the Ulaid.[9][10][11] Ulaid was also known as Cóiced Ulad, the "Fifth of Ulster", and was one of the legendary five provinces of Ireland. After the subsequent loss of territory to the Airgíalla and Northern Uí Néill, the eastern remnant of the province that formed medieval Ulaid was alternatively known as in Cóiced, in reference to the unconquered part of Cóiced Ulad.[5]

The Ulaid are likely the Ούολουντιοι (Uoluntii or Voluntii) mentioned in Ptolemy's 2nd century Geographia.[12] This may be a corruption of Ούλουτοι (Uluti). The name is likely derived from the Gaelic ul, meaning "beard".[13] The late 7th-century writer, Muirchú, spells Ulaid as Ulothi in his work the Life of Patrick.[14]

Ulaid has historically been anglicised as Ulagh or Ullagh[15] and Latinized as Ulidia or Ultonia.[2][3][4] The latter two have yielded the terms Ulidian and Ultonian. The Irish word for someone from Ulaid is Ultach (also spelt as Ultaigh and Ultagh),[2][16] which in Latin became Ultonii and Ultoniensis.[2]

Ulaid gave its name to the province of Ulster, though the exact composition of it is disputed: it may derive from Ulaidh with or without the Norse genitive s and Irish tír ("land, country, earth"),[17][18] or else the second element may be Norse -ster (meaning "place", common in Shetland and Norway).[19][20]

The Ulaid are also referred to as being of the Clanna Rudraige, a late form of group name.[21]

Population groups within Ulaid

According to historical tradition, the ruling dynasties of the Ulaid were either of the Ulaid population-group or the Cruthin. Medieval Irish genealogists traced the descent of the Ulaid from the legendary High King of Ireland, Rudraige mac Sithrigi.[22] The Cruthin on the other hand is the Irish term for the Picts, and are stated as initially being the most powerful and numerous of the two groupings.[7] The terms Ulaid and Cruthin in early sources referred to the Dál Fiatach and Dál nAraidi respectively, the most powerful dynasties of both groups.[7]

The general scholarly consensus since the time of Eoin MacNeill has been that the Ulaid were kin to the Érainn,[23] or at least to their royal families, sometimes called the Clanna Dedad, and perhaps not their nebulous subject populations.[24] T. F. O'Rahilly notably believed the Ulaid were an actual branch of the Érainn.[25] Also claimed as being related to the Ulaid are the Dáirine, another name for the Érainn royalty, both of which may have been related or derived from the Darini of Ptolemy.[26]

There is uncertainty however over the actual ancestry of the people and dynasties within the medieval over-kingdom of Ulaid. Those claimed as being descended from the Ulaid people included medieval tribes that were said to be instead of the Cruthin or Érainn,[21] for example:

- the Dál Riata, Dál Fiatach, and Uí Echach Arda are counted as being of the Ulaid. The Dál Riata and Dál Fiatach however professed to be of Érainn descent.[21][27] Despite this the term Ulaid still referred to the Dál Fiatach until the Anglo-Norman conquest of the over-kingdom in the late 12th century.[7]

- the Conaille Muirtheimne, Dál nAraidi and Uí Echach Cobo are counted as being of the Cruthin. However, after the 8th century, the Síl Ír—the book of genealogies on the descendants of the mythical Ír—focuses on the theme that they are the fír Ulaid, "the true Ulaid".[28] The Dál nAraidi still maintained the claim in the 10th century, long after their power declined.[7][21][27]

History of the over-kingdom

Early history

Ptolemy's Geographia, written in the 2nd century, places the Uoluntii or Voluntii in the southeast of what is now Ulster, somewhere south of the River Lagan and north of the River Boyne. To their north were the Darini and to their south were the Eblani. Muirchú's "Life of Patrick", written in the 7th century, also says that the territory of the Ulothi lay between the Lagan and the Boyne.[29] In the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology—which survives in texts from the 8th century onward—the pre-historic Ulaid are said to dominate the whole north of Ireland, their southern border stretching from the River Boyne in the east to the River Drowes in the west, with their capital at Emain Macha (Navan Fort) near present-day Armagh, County Armagh.[7][18] According to legend, around 331 AD the Three Collas invaded Ulaid, destroyed its ancient capital Emain Macha, and restricted Ulaid to the eastern part of its territory: east of the Lower Bann and Newry River.[30][31] It is said that the territory the Three Collas conquered became the kingdom of Airgíalla.[30] Another tradition that survived until the 11th century dated the fall of Emain Macha to 450 AD—within the time of Saint Patrick—which may explain why he chose Armagh, near Emain Macha, as the site of his episcopacy, as it would then still be under Ulaid control.[31] It may also explain why he was buried in eastern Ulster in the restricted territory of the Ulaid rather than at Armagh, as it had by then come under Airgíallan control.[31] It is likely that the Airgíalla were not settlers in Ulaid territory, but indigenous tribes;[32] most of whom were vassals of the Ulaid before casting off Ulaid overlordship and becoming independent.[33] It has been suggested that the Airthir—in whose lands lay Emain Macha—were originally an Ulaid tribe before becoming one of the Airgíalla.[34]

Towards the end of the 5th century, the Ulaid sub-group Dál Riata, located in the Glens of Antrim, had started settling in modern-day Scotland, forming a cross-channel kingdom.[35] Their first settlements were in the region of Argyll, which means "eastern province of the Gael".[35]

It is to these boundaries that Ulaid entered the historic period in Ireland in the 6th century, though the Dál nAraidi still held territory west of the Bann in County Londonderry.[7] The emergence of the Dál nAraidi and Dál Fiatach dynasties may have concealed the dominance of earlier tribal groupings.[7]

6th to 7th centuries

By the mid-6th century, the Dál Riata possessions in Scotland came under serious threat from Bridei I, king of the Picts, resulting in them seeking the Northern Uí Néill's aid.[35] The king of Dál Riata, Áedán mac Gabráin, had already granted the island of Iona off the coast of Scotland to the Cenél Conaill prince and saint, Columba, who in turn negotiated an alliance between the Northern Uí Néill and Dál Riata in 575 at Druim Ceit near Derry.[35] The result of this pact was the removal of Dál Riata from Ulaid's overlordship allowing it to concentrate on extending its Scottish domain.[35] That same year either before or after the convention of Druim Ceit, the king of Dál Riata was killed in a bloody battle with the Dál nAraidi at Fid Euin.[36]

In 563, according to the Annals of Ulster, an apparent internal struggle amongst the Cruthin resulted in Báetán mac Cinn making a deal with the Northern Uí Néill, promising them the territories of Ard Eólairgg (Magilligan peninsula) and the Lee, both west of the River Bann.[7] As a result, the battle of Móin Dairi Lothair (modern-day Moneymore) took place between them and an alliance of Cruthin kings, in which the Cruthin suffered a devastating defeat.[7] Afterwards the Northern Uí Néill settled their Airgíalla allies in the Cruthin territory of Eilne, which lay between the River Bann and the River Bush.[7] The defeated Cruthin alliance meanwhile consolidated themselves on Dál nAraidi.[7]

The Dál nAraidi king Congal Cáech took possession of the overlordship of Ulaid in 626, and in 628 killed the High King of Ireland, Suibne Menn of the Northern Uí Néill in battle.[37] In 629, Congal led the Dál nAraidi to defeat against the same foes.[7] In an attempt to have himself installed as High King of Ireland, Congal made alliances with Dál Riata and Strathclyde, which resulted in the disastrous Battle of Moira in 637, in modern-day County Down, which saw Congal slain by High King Domnall mac Áedo of the Northern Uí Néill and resulted in Dál Riata losing possession of its Scottish lands.[37]

The Annals of Ulster record that in 668, the battle of Bellum Fertsi (modern-day Belfast) took place between the Ulaid and Cruithin, both terms which then referred to the Dál Fiatach and Dál nAraide respectively.[7]

Meanwhile, the Dál nAraidi where still resisting the encroaching Northern Uí Néill and in 681, Dúngal Eilni, king of the Dál nAraidi, and his ally Cenn Fáelad of Ciannachta were killed at Dún Cethirinn.[7]

8th to 10th centuries

By the 8th century the territory of the Ulaid shrunk to east of the Bann into what is now the modern-day counties Antrim, Down and Louth.[18] In either 732 or 735, the Ulaid suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Cenél nEógain led by Áed Allán in the battle of Fochart in Magh Muirthemne,[38] which saw the king of Ulaid, Áed Róin, decapitated.[39] As a result, the Cenél nEógain brought Conaille Muirthemne under their suzerainty.[38][40][41]

The taking over of the Ulaid's ancestral lands by first the Northern Uí Néill and the end of their glory led to a constant antagonism between them.[18] It was in the 8th century that the kingdom of Dál Riata was overrun by the Dál nAraidi.[3]

The Dál Fiatach dynasty held sway over Ulaid until the battle of Leth Cam in 827, when they attempted to remove Airgíalla from Northern Uí Néill dominance.[14] The Dál Fiatach may have been distracted by the presence of at least one Viking base along Strangford Lough, and by the end of the century, the Dál nAraidi had risen to dominance over them. However, this only lasted until 972, when Eochaid mac Ardgail restored Dál Fiatach's fortunes.[14]

During the 9th and 10th centuries, the Vikings had founded several bases in Ulaid, primarily at Annagassan, Carlingford Lough, Lough Neagh, and Strangford Lough.[42] There was also a significant port at Ulfreksfjord, located at Latharna, present-day Larne, County Antrim.[42] All but Ulfreksfjord were destroyed by the combined efforts of the Ulaid and the Northern Uí Néill, however as a result they deprived themselves of the economic advantages provided by prosperous Viking settlements.[42]

11th century

In 1000 the Viking king of Dublin, Sigtrygg Silkbeard, was expelled by Brian Boru the High King of Ireland, and was refused sanctuary by the Ulaid.[43] Eventually Sigtrygg was forced to return to Dublin and submitted to Brian.[44] Sigtrygg didn't forget the Ulaid's refusal,[43] and in 1001 his fleet plundered Inis Cumhscraigh and Cill Cleithe in Dál Fiatach, taking many prisoners.[45] Sigtrygg's forces also served in Brian's campaigns against the Ulaid in 1002 and 1005.[43][46]

At Craeb Telcha in 1003 the Northern Uí Néill and Ulaid fought a major battle, the Ulaid inauguration site.[14][18][47] Here Eochaid mac Ardgail, and most of Ulaid's nobility were slaughtered, along with the Northern Uí Néill king.[14][18] The result was a bloody succession war amongst the princes of the Dál Fiatach, who also had to war with the Dál nAraidi who eyed the kingship.[48]

In 1005, Brian Boru, marched north to accept submissions from the Ulaid, and set-up camp at Emain Macha possibly with the intention of exploiting the symbolism it held for the Ulaid.[48] From here, Boru marched to the Dál nAraidi capital, Ráith Mór, where he received only the submissions of their king and that of the Dál Fiatach.[48] This however appears to have been the catalyst for a series of attacks by Flaithbertach Ua Néill, king of the Cenél nEógain, to punish the Ulaid.[49] In 1006, an army led by Flaithbertach marched into Leth Cathail and killed its king, followed by the slaying of the heir of Uí Echach Cobo at Loughbrickland.[49]

The battle of Craeb Telcha resulted in the inability of the Ulaid to provide any useful aid to Boru, when in 1006 he led an army made up of men from all over Ireland in an attempt to force the submission of the Northern Uí Néill.[18][49] Having marched through the lands of the Cenél Conaill and Cenél nEógain, Boru led his army across the River Bann at Fersat Camsa (Macosquin) and into Ulaid, where he accepted submissions from the Ulaid at Craeb Telcha, before marching south and through the traditional assembly place of the Conaille Muirtheimne at i n-oenach Conaille.[49]

Flaithbertach Ua Néill continued his attacks on Ulaid in 1007, attacking the Conaille Muirtheimne.[49] In 1011, the same year Boru finally achieved hegemony over the entire of Ireland, Flaithbertach launched an invasion of Ulaid, and after destroying Dún Echdach (Duneight, south of Lisburn) and the surrounding settlement, took the submission of the Dál Fiatach, who had the Ulaid kingship, thus removing them from Boru's over-lordship.[50] The next year, Flaithbertach raided the Ards peninsula and took an uncountable number of spoils.[50]

At Ulfreksfjord in 1018, a combined force of native Irish, led by a king called Conchobar, and their Norse allies, led by Eyvind Urarhorn, defeated a major Viking expedition launched by the Earl of Orkney, Einar Sigurdsson, who was aiming to re-assert his father's lordship over the seaways between Ireland and Scotland.[51][52] In 1022, Niall mac Eochaid, the king of Ulaid, inflicted a major defeat on Sigtrygg's Dublin fleet, decimating it and taking its crew captive.[53][54] Niall followed up this victory in 1026 attacking Finn Gall, a Viking settlement just north of Dublin itself.[53][54]

Sigtrygg's nephew, Ivar Haraldsson, plundered Rathlin Island just off the north coast of Ulaid in 1038 and again in 1045.[55] The latter attack saw Ímar kill Ragnall Ua Eochada, the heir-apparent of Ulaid and brother of Niall mac Eochaid, along with three hundred Ulaid nobles.[55][56][57] In retribution Niall again attacked Finn Gall.[55] In 1087, a son of the king of Ulaid, allied with two grandsons Ragnall, attacked the Isle of Man in a failed attempt to oust Godred Crovan, king of Dublin and the Isles.[58][59][60]

At the end of the 11th century, the Ulaid had a final revival under Donn Sléibe mac Echdacha, from whom descended the Mac Dúinn Shléibe—anglicised MacDonlevy—kings that ruled Ulaid in the 12th century, with the Dál Fiatach kingship restricted to their dynasty after 1137.[61] They developed close ties with the kingdom of the Isles.[14] The Mac Dúinn Shléibe kings desperately maintained the independence of Ulaid from the Mac Lochlainn rulers of the Northern Uí Néill.[3]

12th century

By the beginning of the 12th century the Dál nAraidi, ruled by the Ó Loingsigh (O'Lynch), had lost control of most of Antrim to the Ua Flainn (O'Lynn) and became restricted to a stretch of land in south Antrim with their base at Mag Line (Moylinny). The Ua Flainn were the ruling sept of the Airgíallan Uí Thuirtre as well as rulers of Fir Lí, both of which lay west of the River Bann. In a process of gradual infiltration by marital and military alliances as well as growing pressure from the encroaching Cenél nEógain, they moved their power east of the Bann. Once they had come to prominence in Antrim the Ua Flainn styled themselves as king of Dál nAraidi, Dál Riata, and Fir Lí, alongside their own Uí Thuirtre.[3]

By 1130, the most southerly part of Ulaid, Conaille Muirtheimne, had been conquered by Donnchad Ua Cerbaill, king of Airgíalla.[62] The part of Muirtheimne called Cualigne was subsequently settled by the Airgíallan Uí Méith (from which Omeath derives its name).[62]

The earliest Irish land charter to survive is that of the grant in 1157 of land to the Cistercians in Newry, which lay in Uí Echach, by the High King Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn.[63] This grant was made with the consent of the king of Ulaid, Cú Ulad Mac Dúinn Sléibe, and the king of Uí Echach, Domnall Ua hÁeda.[63]

The Annals of Ulster record that in April 1165, the Ulaid, ruled by Eochaidh Mac Dúinn Sléibe, turned against Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, and attacked the Uí Méith as well as the Uí Breasail in modern barony Oneilland East, County Armagh (which was also formerly part of Ulaid), and the Dál Riata.[64] In retaliation Mac Lochlainn led a force consisting of the Northern Uí Néill and Airgíalla into Ulaid killing many and expelling Eochaid from the kingship.[64] In September Eochaid tried to reclaim the kingship, however was expelled by his own people who feared reprisals from Mac Lochlainn, upon whose command had Eochaid confined by Ua Cerbaill.[64] The next month Mac Lochlainn led another raid into Ulaid, receiving their hostages along with a large amount of their treasure.[64] Later that same month Ua Cerbaill along with Eochaid held a meeting with Mac Lochlainn where Eochaid requested the kingship of Ulaid in return for the hostages of all Ulaid, which included the son of every chief along with his own daughter.[64] Eochaid also gave Mac Lochlainn a considerable amount of treasure along with the territory of Bairrche, and the townland of Saul.[63][64] In turn, Mac Lochlainn swore an oath to the Bishop of Armagh amongst other nobles for his good behaviour. Mac Lochlainn then give Bairrche to Ua Cerbaill for his part in mediating what turned out to be short-lived reconciliation.[62][64][65] Over the following century, the Airgíallan Mughdorna would settle Bairrche, and from them derives its present-day name of Mourne.[62] Despite his oath, Muirchertach had Eochaid seized and blinded, after which his allies abandoned him, and he was reduced to a handful of followers. With sixteen of these closest associates, he was killed in 1166.

In 1170 Eochaid's brother Magnus who had become king of Ulaid expelled the Augustinian canons from Saul.[63]

Ulaid and the Normans

Despite the turmoil amongst the Ulaid, they continued to survive but not for much longer. In 1177 Ulaid was invaded by the Normans led by John de Courcy, who in a surprise attack captured and held the Dál Fiatach capital, Dún De Lethglaise (Downpatrick), forcing the Ulaid over-king, Ruaidrí Mac Duinn Sléibe (Rory MacDonleavy), to flee.[66][67] A week later, Mac Duinn Sléibe returned with a great host from across Ulaid, and despite heavily outnumbering de Courcy's forces, were defeated.[68][69] In another attempt to retake Dún De Lethglaise, Mac Duinn Sléibe followed up with an even greater force made up a coalition of Ulster's powers that included the king of the Cenél nEógain, Máel Sechnaill Mac Lochlainn, and the chief prelates in the province such as the archbishop of Armagh and the bishop of Down.[68][69] Once again however the Normans won, capturing the clergy and many of their relics.[68][69]

In 1178, after John de Courcy had retired to Glenree in Machaire Conaille (another name for Conaille Muirtheimne), Mac Duinn Sléibe, along with the king of Airgíalla, Murchard Ua Cerbaill (Murrough O'Carroll), attacked the Normans, killing around 450, and suffering 100 fatalities themselves.[70]

Despite forming alliances, constant inter-warring amongst the Ulaid and against their Irish neighbours continued oblivious to the threat of the Normans.[67] De Courcy would take advantage of this instability and over the following years, despite some setbacks, set about conquering the neighbouring districts in Ulaid shifting the focus of power.[66][67]

By 1181, Mac Duinn Sléibe and Cú Mide Ua Flainn, the king of Uí Thuirtre and Fir Lí in County Antrim, had come around and served loyally as sub-kings of de Courcy.[71] Mac Duinn Sléibe, possibly inspired by the chance to restore Ulaid to its ancient extent, may have encouraged de Courcy to campaign westwards, which saw attacks on Armagh in 1189 and then Derry and the Inishowen peninsula in 1197.[71]

De Courcy would style himself as princeps Ultoniae, "master of Ulster", and ruled his conquests like an independent king.[67] The Uí Echach Coba in central and western Down however escaped conquest.[66]

In 1199 King John I of England sent Hugh de Lacy to arrest de Courcy and take his possessions. In 1205, de Lacy was made the first Earl of Ulster, founding the Earldom of Ulster, with which he continued the conquest of the Ulaid. The earldom would expand along the northern coast of Ulster all the way to the Cenél nEógain's old power-base of Inishowen.

Until the end of the 13th century, the Dál Fiatach, still led by the Mac Dúinnshléibe, retained a fraction of their power being given the title of rex Hibernicorum Ulidiae, meaning "king of the Irish of Ulaid".[72] The Gaelic title of rí Ulad, meaning "king of Ulster", upon the extinction of Dál Fiatach was usurped by the encroaching Ó Néills of the Cenél nEógain.[72]

Religion

Ulaid was the location where the future patron saint of Ireland, Saint Patrick, was held during his early captivity.[73] It is here that he made the first Irish converts to Christianity, with the Dál Fiatach the first ruling dynasty to do so.[73] Patrick died at Saul, and buried at Dún De Lethglaise, which in the 13th century was renamed Dún Phádraig, which became Anglicised as Downpatrick.[74]

When Ireland was being organised into a diocesan system in the 12th century, the following dioceses where created based on the territory of the main dynasties of the Ulaid: the diocese of Down, based on the territory of the Dál Fiatach, with its cathedral at Bangor, however later moved to Downpatrick by John de Courcy; and the diocese of Connor, based on the territory of the Dál nAraidi.[75][76] Around 1197 the diocese of Down was split in two with the creation of the diocese of Dromore, based on the territory of the Uí Echach Cobo, with its cathedral at Dromore.[75][76]

Principal churches/monasteries

The chief churches, or more accurately monasteries, of the main sub-kingdoms of Ulaid were:

- Mag Bile (modern Irish: Maigh Bhile, meaning "plain of [the] sacred trees"), now known as Movilla in County Down.[77] It was the chief church of the Dál Fiatach, and linked with their ecclesiastical origins, having been founded circa 540 by St. Finnian of Movilla, who was of the Dál Fiatach.[77][78] The name Mag Bile suggests that this monastery was purposely built on the site of an ancient sacred tree.[77]

- Bennchair (modern Irish: Beannchar, possibly meaning "place of points"), now known as Bangor in County Down.[79] Built circa 555 or 559 by St. Comgall of the Dál nAraidi in what was Dál Fiatach territory, it was one of the main monastic foundations in Ireland.[78][79]

- Condaire (modern Irish: Coinnire, meaning "[wild-]dog oak-wood"), now known as Connor in County Antrim.[80] It was the chief church of the Dál nAraidi located in the minor-kingdom of Dál Sailni, and was founded by St. Mac Nisse.[80][81][82] It would become the cathedral for the diocese of Connor.

- Airther Maigi (modern Irish: Oirthear Maí, meaning "the east of the plain"), now known as Armoy in County Antrim.[83] It was the chief church of the Dál Riata founded by St. Olcan; however, after Dál nAraidi expansion in the 7th century it lost its episcopal status and was superseded by the church of Connor.[82]

- Droma Móir (modern Irish: Droim Mór, meaning "big ridge"), now known as Dromore in County Down.[84] It became the chief church of the Uí Echach Cobo, and was founded circa 510 by St. Colmán.[85] It would become the cathedral for the diocese of Dromore.

Artefacts

Although Francis John Byrne describes the few La Tène artefacts discovered in Ireland as 'rather scanty',[86] most of the artefacts (mostly weapons and harness pieces) have been found in the north of Ireland, suggesting 'small bands of settlers (warriors and metalworkers) arrived' from Britain in the 3rd century BC, and may have been absorbed into the Ulaid population.[87]

Kingdoms, dynasties, and septs

By the 12th century Ulaid was divided into four main dynastic sub-kingdoms, each consisting of smaller petty-kingdoms:

- Dál Fiatach, an Ulaid people based at Dún De Lethglaise (present-day Downpatrick, County Down), who dominated the over-kingship of Ulaid and had interests in the Isle of Man.[18] Their principal sept were the Mac Duinnshléibhe.

- Dál nAraidi a Cruithin people, dominated by the Dál nAraidi of Magh Line based at Ráith Mór (near present-day Antrim town, County Antrim). They were the Dál Fiatach's main challengers for the over-kingship.[18] Their principal sept were the Uí Choelbad.

- Uí Echach Cobo, a Cruithin sept, kin with the Dál nAraidi, who also challenged for the over-kingship of Ulaid.[88] They were based in modern-day County Down, possibly at Cnoc Uí Echach (Knock Iveagh).[89] Their principal sept were the Mag Aonghusa;

- Uí Tuirtri, originating from Airgíalla they took control of most of Dál nAraidi's territory. Its principal sept was the Uí Fhloinn.

In the 10th-century revision of the Lebor na Cert, the following twelve Ulaid petty-kingdoms are given as paying stipends to the king of Ulaid:[90]

- Dál nAraidi of Magh Line

- Cobha, ruled by the Uí Echach Cobo

- Dál Riata, based in the Glens of Antrim

- Airrther, a district located in eastern County Armagh

- Uí Erca Céin, a branch of the Dál nAraidi

- Leth Cathail, a branch of the Dál Fiatach, located in and around the modern barony of Lecale, County Down[91]

- Conaille Muirtheimne, close kin of the Uí Echach Cobo, located in and around the modern barony of Dundalk, County Louth[91]

- Dál mBuinne, also known as the Muintir Branáin, a branch of the Dál nAraidi located along the border area between County Antrim and Down[91]

- Uí Blathmaic, a branch of the Dál Fiatach whose territory was located in the north-western part of the barony of Ards and part of Castlereagh;[91]

- Na hArda, ruled by the Uí Echach Arda, a branch of the Dál Fiatach whose territory was located in the northern part of the Ards peninsula[92]

- Boirche, alias Bairrche, a branch of the Dál Fiatach located in what is now the barony of Mourne in southern County Down

- Duibhthrian, west of Strangford Lough, County Down.

Other territories and dynasties within Ulaid included:

- Cuailgne, located in the area of Carlingford Lough and Dundalk, County Louth. Their name is preserved in the name of the parish of Cooley,[91] as well as the Cooley Peninsula. Cooley is the location of the Táin Bó Cúailnge or Cattle Raid of Cooley.

- Dál Sailni, a client-kingdom of the Dál nAraidi of Magh Line. Whilst the Uí Choelbad dynasty of Dál nAraidi supplied the principal kings, the Dál Sailni held the principal church of Connor.[81] After the Viking period, the church of Connor and the territory of the Dál Sailni were taken over by the Uí Tuirtri.[81]

- Cineál Fhaghartaigh, an offshoot of the Uí Echach Cobo, who at one time held the modern baronies of Kinelarty, Dufferin, and part of Castlereagh.[91]

- Monaig, a people whose locale is disputed. The annals and historians make mention of several different Monaigs: the Monaigh Uladh, in the area of Downpatrick; Monaich Ulad of Rusat; Monaigh at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh; Monaigh Aird, in County Down; the Cenél Maelche/Mailche in Antrim, County Antrim, "alias Monach"; Magh Monaigh; Monach-an-Dúin in Cath Monaigh, possibly in Iveagh, County Down. The ancient Manaigh/Monaigh who settled near Lough Erne, are associated with the Menapii, a Belgae tribe from northern Gaul.[91]

Descended houses

The first king of Scotland, Kenneth MacAlpin, founder of the House of Alpin, is said to descend from the mid-6th-century king of Dál Riata, Gabrán mac Domangairt. Along with this, the following Scottish Highland houses are reputed to be of Ulaid descent: McEwen, MacLachlan, McNeills, and the MacSweens.[93][94][95] The royal House of Stuart is also claimed as being descended from the Ulaid.[96]

In medieval literature

According to medieval pseudo-historians a group of brothers known as the Three Collas in the 4th century founded the over-kingdom of Airgíalla after a decisive defeat of the Ulaid, and afterwards destroyed their ancient capital Emain Macha. This however is a fabrication.[7]

The Ulaid feature in Irish legends and historical traditions of prehistoric times, most notably in the group of sagas known as the Ulster Cycle. These stories are set during the reign of the Ulaid king Conchobar mac Nessa at Emain Macha (Navan Fort, near Armagh) and tell of his conflicts with the Connachta, led by queen Medb and her husband Ailill mac Máta. The chief hero is Conchobar's nephew Cú Chulainn, and the central story is the proto-epic Táin Bó Cúailnge, "The Cattle Raid of Cooley".

In this period Ireland is said to have been divided into five independent over-kingdoms—or cuigeadh, literally meaning "a fifth"—of which Ulaid was one, with its capital at Emain Macha.[97][98][99] Medieval pseudo-historians called this era Aimser na Coicedach, which has been translated as: "Time of the Pentarchs";[98] "Time of the Five Fifths";[97] and "Time of the provincial kings".[100] It was also described as "the Pentarchy".[98][99]

In some stories Conchobar's birth and death are synchronised with those of Christ, which creates an apparent anachronism in the presence of the Connachta. The historical Connachta were a group of dynasties who traced their descent to the legendary king Conn Cétchathach, whose reign is traditionally dated to the 2nd century.[101] However, the chronology of early Irish historical tradition is inconsistent and highly artificial.[102] One early saga makes Fergus mac Léti, one of Conchobar's predecessors as king of the Ulaid, a contemporary of Conn,[103] and Tírechán's 7th century memoir of Saint Patrick says that Cairbre Nia Fer, Conchobar's son-in-law in the sagas, lived only 100 years before the saint, i.e. in the 4th century.[104]

Kenneth Jackson, based on his estimates on the survival of oral tradition, also suggested that the Ulster Cycle originated in the 4th century.[105] Other scholars, following T. F. O'Rahilly, propose that the sagas of the Ulster Cycle derive from the wars between the Ulaid and the midland dynasties of the Connachta and the nascent Uí Néill in the 4th and 5th centuries, at the end of which the Ulaid lost much of their territory, and their capital, to the new kingdoms of the Airgíalla.[106] Traditional history credits this to the Three Collas, three great-great-great-grandsons of Conn, who defeated the Ulaid king Fergus Foga at Achad Lethderg in County Monaghan, seized all Ulaid territory west of the Newry River and Lough Neagh, and burned Emain Macha. Fergus Foga is said to have been the last king of the Ulaid to reign there. The Annals of the Four Masters dates this to AD 331.[107] O'Rahilly and his followers believe the Collas are literary doublets of the sons of Niall Noígiallach, eponymous founder of the Uí Néill, who they propose were the true conquerors of Emain in the 5th century.[108]

The Kings of Tara in the Ulster Cycle are the kindred of the Ulaid, the Érainn, and are generally portrayed sympathetically, especially Conaire Mór. It was remembered that the Connachta and Uí Néill had not yet taken the kingship. Tara was later occupied by the Laigin, who are to some extent strangely integrated with the Connachta in the Ulster Cycle.[109] The latter later took the midlands from the Laigin and their historical antagonism is legendary. The Érainn, led by Cú Roí, also rule in distant Munster and, while presented as deadly rivals of the Ulaid, are again portrayed with unusual interest and sympathy.

Cultural impact

There two known communities in North Carolina, the United States, that are likely to have been named after Ulaid - Mount Ulla and Ulah.[110]

The Ulaid have inspired the name of traditional Irish group Ulaid featuring Dónal O'Connor, John McSherry & Seán Óg Graham who have released two critically acclaimed albums.

See also

References

- Connolly (2007), p. 589.

- Hack (1901), p. 38.

- Cosgrove (2008), p. 17.

- Irish Archaeological Society (1841). "Volume 1". Tracts Relating to Ireland Publications. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- MacNeill (1919), p. 651.

- Fraser (2009), p. 159.

- Cosgrove (2008), pp. 212–5.

- Neafsey, Edward (2002). The Surnames of Ireland: Origins and Numbers of Selected Irish Surnames. Irish Roots. p. 168. ISBN 9780940134973.

- Byrne (2001), p. 46.

- Duffy (2014), pp. 7–8

- MacNeill (1911/2), p. 60.

- Ptolemy. "Book II, Chapter 1. Location of Hibernia island of Britannia". Geographia. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Karl Horst Schmidt, "Insular P- and Q-Celtic", in Martin J. Ball and James Fife (eds.), The Celtic Languages, Routledge, 1993, p. 67

- Duffy (2005), p. 493.

- Lewis, Samuel (1837). "County Down". A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Robert Bell; The book of Ulster Surnames, page 180. The Blackstaff Press, 2003. ISBN 0-85640-602-3

- Bardon (2005), p. 27.

- Duffy (2014), pp. 26–27

- Taylor, Rev. Isaac (1865). Words and Places: Or, Etymological Illustrations of History, Ethnology, and Geography. Macmillan & Co. p. 182. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Froggart, Richard. "Professor Sir John Byers (1853–1920)". Ulster History Circle. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Chadwick, Hector Munro (21 March 2013). The Early Cultures of North-West Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107686557. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- O'Rahilly 1946, p. 480

- Eoin MacNeill, "Early Irish Population Groups: their nomenclature, classification and chronology", in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (C) 29. (1911): 59–114

- Eoin MacNeill, Phases of Irish History. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son. 1920.

- T. F. O'Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, 1946, p. 81

- Discussed at length by O'Rahilly 1946

- Thornton, p. 201.

- Kelleher, p. 141.

- Duffy (2005), p.817

- OBrien, pp. 170–1.

- Schlegel, pp. 173–4.

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí. A New History of Ireland I: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Oxford University Press, 2005. p.202

- Byrne (2001), p.73

- Dumville, David. Saint Patrick. Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 1999. p. 151

- Bardon (2005), p. 17.

- Fraser (2007), p. 317.

- Bardon (2005), pp. 20–1.

- Wiley, p. 19.

- Mac Niocaill, p. 124.

- Byrne (2001), p. 118.

- Charles-Edwards, p. 573.

- Cosgrove (2008), p. 38.

- Hudson, pp. 86–7.

- Ó Corráin (1972), p 123.

- "Annals of the Four Masters, 993 AD". University College Cork. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Hudson, p. 95.

- Placenamesni.org. "Crew, County Antrim". Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Duffy (2014), pp. 138–9

- Duffy (2014), pp. 151–4

- Duffy (2014), pp. 168–9

- Pedersen, p. 271.

- Sturluson, p. 330.

- Pedersen, p. 231.

- Hudson, pp. 108–9.

- Hudson, p. 136.

- "Annals of Tigernach, 1045 AD". University College Cork. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Annals of the Four Masters, 1045 AD". University College Cork. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Pedersen, p. 233.

- Oram (2011), p. 32.

- Corpus of Electronic Texts Edition - Annals of Ulster, 1087 AD

- Byrne (2001), p. 128.

- Cosgrove (2008), p. 16.

- Cosgrove (2008), p. 12.

- Corpus of Electronic Texts Edition - Annals of Ulster, 1165 AD

- Magoo - The Mughdorna

- Bardon (2005), pp. 33–37

- Adamson (1998), pp. 116–7

- Bardon, page 33–5.

- Cosgrove (2008), p. 115.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". University College Cork. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Cosgrove (2008), p. 116.

- Stockman, p. xix.

- O'Hart (1976), pp. 427 & 819.

- "Downpatrick". The Saint Patrick Centre. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- Keenan, pp. 139–140.

- Keenan, pp. 347–349.

- Placenamesni.org. "Movilla, County Down". Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Carey, p. 97.

- Placenamesni.org. "Bangor, County Down". Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Placenamesni.org. "Connor parish". Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Charles-Edwards, p. 63.

- Charles-Edwards, pp. 59–60.

- Placenamesni.org. "Armoy, County Antrim". Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Placenamesni.org. "Dromore, County Down". Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "About Us". Diocese of Down and Dromore. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Byrne, Francis John, Irish Kings and High-Kings. Four Courts Press. 2nd revised edition, 2001.

- Connolly, S.J, The Oxford companion to Irish history. Oxford University Press. 2nd edition, 2007.

- Placenames NI. "Iveagh". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Placenames NI. "Drumballyroney". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Dobbs, p. 78.

- Walsh, Dennis. "Ancient Uladh, Kingdom of Ulster". Ireland's History In Maps. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Stockman, p. 3.

- John O'Hart, Irish Pedigrees; or, The Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation, 5th edition, in two volumes, originally published in Dublin in 1892, reprinted, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1976, Vol. 1, p 604

- John O'Hart, Irish Pedigrees; or, The Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation, 5th edition, in two volumes, originally published in Dublin in 1892, reprinted, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1976, Vol. 1, pp 558–559

- Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk The Highland Clans (1982) New York: Clarkson N. Potter ISBN 0-517-54659-0, pp. 117–119, The Donlevy are also reputed to have given rise in Scotland to the Highland MacEwens, Maclachlans, MacNeils and MacSweens.

- again, G.H. Hack Genealogical History of the Donlevy Family Columbus, Ohio: printed for private distribution by Chaucer Press, Evans Printing Co. (1901), p 38 (Wisconsin Historical Society Copy) "From the chiefs of the Dalriadians were descended the ancient Scottish kings and also the House of Stuart."

- Hurbert, pp. 169–171

- Eoin MacNeill (1920). The Five Fifths of Ireland.

- Hogan (1928), p. 1.

- Stafford & Gaskill, p. 75

- R. A. Stewart Macalister (ed. & trans.), Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland Part V, Irish Texts Society, 1956, p. 331–333

- Byrne 2001, p. 50–51.

- D. A. Binchy (ed. & trans.), "The Saga of Fergus mac Léti", Ériu 16, 1952, pp. 33–48

- Ludwig Bieler (ed. & trans.), The Patrician Texts in the Book of Armagh, Tírechán 40

- Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson, The Oldest Irish Tradition: a Window on the Iron Age, Cambridge University Press, 1964

- O'Rahilly 1946, pp. 207–234

- Annals of the Four Masters M322-331

- Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, "Ireland, 400–800", in Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (ed.), A New History of Ireland Vol 1, 2005, pp. 182–234

- Apparently the Laigin had a prehistoric presence in Connacht and may once have been its sovereigns. See Byrne, pp. 130 ff.

- "Etymology of "Mount Ulla" or Where the Place-Name Came From". Mount Ulla Historian. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Adamson, Ian (1998). Dalaradia, Kingdom of the Cruithin. Pretani Press. ISBN 0-948868-25-2.

- Bardon, Jonathan (2005). A History of Ulster. The Black Staff Press. ISBN 0-85640-764-X.

- Bell, Robert (2003). The Book of Ulster Surnames. The Blackstaff Press. ISBN 978-0-85640-602-7.

- Byrne, Francis J. (2001). Irish Kings and High Kings. Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851821969.

- Carey, John (1984). "Scél Tuáin Meic Chairill". Ériu. 35: 93–111.

- Charles-Edwards, T.M. (2000). Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36395-0.

- Cosgrove, Art, ed. (2008). A New History of Ireland, II Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953970-3.

- Connolly, S.J., ed. (2007). Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923483-7.

- Cronnelly, Richard Francis (1864). A History of the Clanna-Rory, Or Rudricians: Descendants of Roderick the Great, Monarch of Ireland. Goodwin, Son and Nethercott.

- Dobbs, Margaret (1945). "The Dál Fiatach". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. Third Series. 8: 66–79.

- Duffy, Seán (2005). Medieval Ireland an Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94052-8.

- Duffy, Seán (2014). Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-6207-9.

- Fraser, James (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2820-9.

- Fraser, James (2007). St Columba and the convention at Druimm Cete: peace and politics at seventh-century Iona. Edinburgh University Press.

- Hack, G.H. (1901). "Genealogical History of the Donlevy Family". Chaucer Press, Evans Printing Co.

- Hogan, James (1928–1929). "The Tricha Cét and Related Land-Measures". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C. 38: 148–235.

- Hudson, Benjamin T (2005). Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in the North Atlantic (Illustrated ed.). United States: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516237-0.

- Hurbert, Henri (12 November 2013). The Greatness and Decline of the Celts. Routledge. ISBN 9781136202926.

- Kelleher, John V. (1968). "The Pre-Norman Irish Genealogies". Irish Historical Studies. 16 (62): 138–153. doi:10.1017/S0021121400021921. S2CID 159636196.

- Keenan, Desmond (2010). Ireland 1170–1509, Society and History. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4535-8431-6.

- MacNeill, John (1911–1912). "Early Irish Population-Groups: Their Nomenclature, Classification, and Chronology". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C. 29: 59–114.

- MacNeill, Eoin (1919). "The Irish Law of Dynastic Succession: Part II". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 8 (32): 640–653.

- Mac Niocaill, Gearoid (1972). Ireland before the Vikings. Gill and Macmillan.

- Meginnes, John Francis (1891). Origin and History of the Magennis Family. Heller Brothers Printing.

- O'Brien, M.A. (1939). "The Oldest Account of the Raid of the Collas (Circa A.D. 330)". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. Third Series. 2: 170–177.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1972). Ireland Before the Normans. Ireland: Gill and Macmillan.

- O'Hart, John (1976). "Heremon Genealogies - Dunlevy, Princes of Ulidia". Irish Pedigrees; or, The Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation (5th ed.). Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company.

- Oram, Richard D. (2011). Domination and Lordship: Scotland, 1070–1230. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1497-4.

- Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Schlegel, Donald M. (1998). "The Origin of the Three Collas and the Fall of Emain". Clogher Record. Clogher Historical Society. 16 (2): 159–181. doi:10.2307/20641355. JSTOR 20641355.

- Stafford, Fiona J., Gaskill, Howard (1998). From Gaelic to Romantic: Ossianic Translations. Rodopi. ISBN 9042007818.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stockman, Gerrard (1992). Volume Two, County Down II, The Ards. ISBN 0-85389-450-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sturluson, Snorri (2009). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. Texas University Press, Austin. ISBN 978-0-292-73061-8.

- Thornton, David E. (2003). Kings, Chronologies, and Genealogies: Studies in the Political History of Early Medieval Ireland and Wales. Occasional Publications UPR. ISBN 978-1-900934-09-1.

- Wiley, Dan M. (2005). "Niall Frossach's True Judgement". Ériu. 55: 19–36. doi:10.3318/ERIU.2005.55.1.19. S2CID 170708492.