Poverty in Mexico

Poverty in Mexico deals with the incidence of poverty in Mexico and its measurement. It is measured based on social development laws in the country and under parameters such as nutrition, clean water, shelter, education, health care, social security, quality and availability of basic services in households, income and social cohesion.[2] It is divided in two categories: moderate poverty and extreme poverty.

| Poverty Headcount Ratio (2010)[1] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Poverty Trend | World Bank | |

| Live with less than $1.00 a day | 0.7% (0.8 mi) | |

| Live with less than $2.00 a day | 4.5% (5.1 million) | |

| Live with less than $2.50 a day | 8.8% (10.9 million) | |

| Live with less than $4.00 a day | 23.7% (26.9 million) | |

| Live with less than $5.00 a day | 33.2% (37.6 million) | |

Poverty is probably one of the main challenges to overcome for any governmental administration; however, it would be important to understand it more thoroughly to see how complex and extensive it is. There are various types of poverty; which are, on the one hand, poverty per se, and on the other, extreme poverty.

According to CONEVAL,[3] the institution designated to measure poverty in Mexico, poverty analysis should not only look at monetary income but also at social factors. Six different lacks serve as indicators in terms of measuring poverty,[3] which are educational backwardness, access to health services, access to social security, access to (decent) food, quality of housing spaces, and finally access to basic services in housing (having a roof to live in and access to certain goods and services).

To be considered poor, it is enough to have an income below the well-being line (income that is less than food and non-food basic basket), regardless of the amount of social deficiencies that the person has, if any.

On the other hand, there is extreme poverty, the most precarious situation in which a person can be,[3] and this is manifested when the income received by a person is less than the food basket and also has three or more lacks previously mentioned.

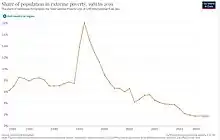

While less than 2% of Mexico's population lives below the international poverty line set by the World Bank, as of 2013, Mexico's government estimates that 33% of the population lives in moderate poverty and 9% lives in extreme poverty,[4] which leads to 42% of Mexico's total population living below the national poverty line.[5] The extreme gap is explained by the government's adoption of the multidimensional poverty method as a way to measure poverty, which outlines that a person with an income above the "international poverty line" or "well being income line", set by the Mexican government, falls in the "moderate poverty" category if he or she has one or more deficiencies related to social rights such as education (did not complete studies), nutrition (malnutrition or obesity), or living standards (access to elemental services such as water or electricity, and secondary domestic assets, such as refrigerators). Extreme poverty is defined by the Mexican government as deficiencies in both social rights and incomes lower than the "well being income line".[6] Additional figures from SEDESOL (Mexico's social development agency) estimate that 6% of the population (7.4 million people) lives in extreme poverty and suffers from food insecurity.[7]

The high numbers of poverty in the country, despite Mexico's positive potential is a recurrent topic of discussion among professionals.[8] Some economists have speculated that in four more decades of continuous economic growth, even with emigration and violence, Mexico will be among the five biggest economies in the world, along with China, the United States, Japan, and India.[9]

Recently, extensive changes in government economic policy[10] and attempts at reducing government interference through privatization of several sectors,[11] allowed Mexico to remain the biggest economy in Latin America [12] up until 2005 when it became the second-largest.[13] Despite these changes, Mexico continues to suffer great social inequality and lack of opportunities.[14] The previous administration made an attempt at reducing poverty in the country by providing more professional and educational opportunities to its citizens, as well as establishing a universal healthcare.[15][16]

Background

Mexico's unequal development between the richer urban zones and the considerably poorer rural zones have been attributed to the fast economic growth that took place during the so-called Mexican miracle, the period in which Mexican economy transitioned from an agricultural economy to an industrial one. This led many people to relocate to the cities. Even though investments were pouring into urban infrastructure, the government couldn't accommodate the rapid influx of people, which led to the development of slums in the outskirts of many Mexican cities. The constant government corruption is another factor to which poverty is frequently attributed.[17] Only in recent years, after various economic setbacks, Mexico has recovered to a level where the middle class, once virtually nonexistent, is beginning to flourish.[18][19][20]

Social stratification, still greatly present in Mexico, can be traced back to the country's origin. In the Colonial Period, before its independence, the upper class was composed of those who owned the land and the lower class was made of those who worked the land. After the Mexican Revolution, the government ceded an estimated 50 percent of the land to the general population, covering a small portion of the gap between the wealthy and the poor.[21] Land ownership continued to be the main source of wealth for Mexicans and has dictated the hierarchy of wealth distribution amongst the population. After the country entered its economic industrial transformation, industrialists, businessmen, and politicians have controlled the direction of wealth in Mexico and have remained among the wealthy.[22] The average individual gross annual income in Mexico in 2002 was US$6,879.37 (2010 dollars).[23] 12.3 percent of the Mexican labor force earns the daily minimum wage or MX$1,343.28 per month (approx. US$111.94 November 2010 exchange rates).[24] 20.5 of the labor force earns twice the minimum wage and 21.4 percent earns up to three times the daily minimum wage while 18.6 earn no more than five daily minimum wages.[24] Only 11.8 percent of the working population earn wages equal or above MX$6,716.40 (US$559.70) per month.[24] According to Jaime Saavedra, World Bank Poverty Manager for Latin America, Mexico has made considerable strides in poverty reduction since the late 1990s, with performance above the Latin American average. Saavedra explained that: "Between 2000 and 2004, extreme poverty fell almost seven percentage points, which can be explained by development in rural areas, where extreme poverty fell from 42.4 per cent to 27.9 per cent. The urban poverty rate, however, got stuck at 11.3 per cent."[25]

Government involvements

Social development began to take place in the form of written policy in the early 1900s.[26] The Mexican Constitution, approved in 1917, outlined the basic social protections citizens are entitled to, including the right to property, education, health care, and employment; and it establishes the federal government responsible for the execution and enforcement of these protections.[27]

The global economic crisis of the late 1920s and forward slowed down any possibility of social development in the country.[28] Between the 1920s and the 1940s the illiteracy levels range between 61.5 and 58 percent, due this the government focused on establishing social protection institutions. By the late 1950s, 59 percent of the population knew how to read and write. In the 2000s only 9.5 percent of the population older than 15 years was illiterated.[26] By the 1960s, individual involvement of some states to increase social development, along with the country's economic growth, as well as employment opportunities and greater income, and the migration of people from the rural states to the urban areas, helped reduced poverty nationwide.[26] The 1970s and 1980s saw the transformation of government and economic policies. The government gave way to flexible foreign trade, deregulation and privatization of several sectors. After the economic crisis of the 1990s, Mexico recovered to become an emerging economic power; however, the number of poor nationwide has remained constant even with the country's overall growth.[29][30]

Regional variation

Historically, southern states like Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero have remained segregated from the rest of the country.[31] Their implementation of infrastructure, social development, education, and economic growth has been poorly accounted for. These states hold the highest levels of illiteracy, unemployment, lack of basic services such as running water and sanitation, overall urban infrastructure, and government establishment.[32] As citizens of the least fortunate states have noticed growth and improvements in other states, many have simply left seeking better opportunities.[33]

Causes of poverty

The reasons for poverty in Mexico are complex and widely extensive.[34][35] There is an agreement that a combination of uneven distribution of wealth and resources sponsored by economic and political agendas to favor the rich and powerful is a major contributor to the millions left behind.[36][37]

Individual condition

In the economic sense, access to insufficient monetary means to afford goods and services becomes the immediate reason to be poor. Because a person's personal income dictates what he or she can afford and what he or she will remain deprived of, the first common cause of poverty is the individual condition.[38] This means, a person's individual circumstances and possibilities create their opportunity for access to goods and services. This condition is triggered by a person's income, education, training or work experience, social network, age, health, and other socio-economic factors:

Lack of and unavailability of education

As population has grown, the number of students enrolled in schools throughout the country has grown tremendously since the 1950s.[39] At the same time, government efforts to accommodate the growing student population, improving the quality of instruction and promoting prevalent school attendance has not been enough and therefore education has not remained among priorities for families who must struggle with poverty.[40][41] 700,000 students grades 1-9 dropped out of school in 2009 in all of Mexico.[42] 7.9 percent (almost 9 million) of the population is illiterate.[42] 73% of Mexican households have at least one member without education or education below the 7th grade.[42] 40 percent of people in the states of Chiapas, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Oaxaca and Guerrero have education below the 7th grade.[43]

Low quality public education

It is difficult to speak of progress anywhere, with such alarming educational lag figures, Mexico has been fighting for years against teacher unions that ask for a lot and give a little in return, that is why the quality of public education is far below of what it should be. It is difficult to access public education, and not very efficient. This is a serious problem because a low-quality early education translates into a poor human development index (HDI),[44] which in turn shows low achievement and no expectations of personal and professional growth in the future, which generates the famous poverty trap.

Underemployment

.jpeg.webp)

Getting an education does not immediately translate to landing better paying jobs or overcoming underemployment in Mexico: According to data compiled by the Civic Observatory for Education, fewer than 20% of recent graduates manage to find an appropriate position during their first round of job-hunting. Although the country has made great strides in education and professional training, the absence of a serious employment policy means that economic expansion is sacrificed so that higher prices can be avoided. That exerts a negative impact on the labor market in both the short and medium term, and on new professionals most of all.[45] Situations like this have caused the standard of living among the urban middle class to deteriorate and as a consequence brings on emigration from this sector to other countries, mainly the United States and Canada.[46] Mexico has an extensive infrastructure of informal economics, which further complicates the measurement of unemployment, as people involved in these jobs are not considered unemployed, while not being officially employed either (ex. housemaids, street sellers, artisans). It is estimated that 59% of the jobs in the country belong to the informal economy.[47]

Birth rate, contraception, and life expectancy

Although Mexico's birth rate has been consecutively declining since the 1970, its population growth still exceeds its ability to pull people out of abject poverty. Contraception is widely used, despite it being a hot-button political and religious issue. Contraception is provided through a government-sponsored program called Mexfam. The average life expectancy has drastically increased from 60 years in 1968, to 77 years in 2012. Rural areas still have the highest birth rates and poverty rates in Mexico, with indigenous populations topping the list.

Other challenges

Mexico does not promote equal opportunity employment despite established laws forbidding most socially-recognized forms of discrimination.[48] The government doesn't become sufficiently involved to promote opportunities to all citizens; including reducing discrimination against middle-age and elder citizens. Over a million of the unemployed face age discrimination and 55% of all unemployed face some form of discrimination when seeking employment.[49] There are virtually no opportunities for individuals with special requirements such as the disabled.[50] As job seekers become older, it is harder for them to get employed as employers tend to seek candidates within the "younger than 35 range". Social security (IMSS) is insufficient and there is a huge gap in proportion to the entire population (50% covered), the work force (30% covered), and the retired (33% covered).[51] There is no unemployment insurance in Mexico.[52]

Insufficient infrastructure

Mexico is a country where investment on infrastructure has remained as unequally distributed as income, especially in rural areas and in the southern states.[53] Because many people establish in rural areas, without government permission, and without paying property taxes, the government does not make significant efforts to invest in overall infrastructure of the entire country, yet it has started to do so until the 1990s.[54] Communities often face a combination of unpaved roads, lack of electricity and potable water, improper sanitation, poorly maintained schools, vandalism and crime, and lack of social development programs.[55][56] The government did not begin to focus on improving and modernizing the federal highway system up until two decades ago when it was composed of two-lane roads; often deathtraps and the scenarios of head-on collisions between truckers and families on vacation.[57] City and state governments often face challenges providing citizens who live on informal commerce with the basic services of urbanized life.[58] To worsen the problem the housing laws often vary greatly from one state to another, with the state of Hidalgo having no housing laws at all.[59] Because of this, higher income communities will invest in the development of their own communities while lower income communities might be deprived of the basics such as running water and drainage in various cases.

- Geography and poverty

The concentration of poverty and distribution of wealth and opportunities is clearly visible from a geographic perspective.[60] The northern region of the country offers higher development while the southern states are the most impoverished. This is clearly the result of states equipped with better infrastructure that others. The states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero are among the least developed in the country. These states hold the highest numbers of indigenous population. As a result, 75 percent of the indigenous population lives on moderate poverty line and 39 percent of these under extreme poverty.[61]

Unemployment

Unemployment in Mexico has been continuous.[14][45] In 2009, the unemployment rate was estimated at 5.5 percent (over 2.5 million).[62] Although that figure is far below the unemployment indexes in the rest of Latin America, the European Union, the United States and much of Asia, Mexico faces a serious problem generating jobs.[63] In spite of splendid macroeconomic indicators that currently exist: continuing low levels of inflation and stability in the nation's currency exchange rate; a sufficient number of formal jobs- at least one million every year to keep up with the growing population- have not been created in over ten years.[64] With the abundance of natural resources in the country- as well as its petroleum wealth, these benefits don't seem to reach many of the people of Mexico who lack job opportunities and the means to raise their standards of living out of poverty and marginalization.[65]

In order to improve present day employment opportunities in Mexico, existing laws and regulations must be replaced for efficient instruments with greater legal certainty; encourage private investment; increase the collection of taxes; stimulate the productivity of businesses and the training of workers; and create more and better jobs.[66]

- Inequitable distribution of income

Mexico's wealth is unevenly distributed among its people where 10 percent of nation's wealthiest have 42.2 percent of all income and 10 percent of the nation's poorest have 1.3 of the remaining income.[67] Carlos Slim, the richest man in Mexico and one of the richest in the world, has a personal fortune equal to 4 to 6 percent of the country's GDP.[68][69] In spite of efforts by government officials during the past three administrations; transition to globalization,[70] the NAFTA agreement;[71] Mexico has been unable to create efficient public policies in order to compensate for the distortion of its market and the poor distribution of national income.[72]

- Obsolete regulatory framework

The absence of basic agreements among Mexico's main political parties for more than ten years has caused a serious backwardness in needed legislation in a number of areas.[73] The current economic framework needs adjustment on virtually all levels including business development opportunities, fair competition, tax collection and tax law; commerce, trade and finance regulations.[74]

- Absent competitive principles

The Mexican economy does not support unprivileged businesses, considering its current standards regarding monopolies, both in the public and private sectors.[75] By law, there are public monopolies: government-owned companies controlling oil and gas, electricity, water, etc.[76] Private sector monopolies and duopolies are found in the media, television, telecommunications, and raw materials.[77] For this reason, clear principles of competitiveness that offer incentives to private investment, both national and foreign, are needed in order for jobs to be created.[78]

Government and politics

Mexico's rampant poverty lagged social development and general public welfare is strongly tied to its politics.[79] Historically, the political system of Mexico has not favored the general population, mainly because it focused to become and be a single-party system of government, largely dubbed "institutionalized" where those in charge had a one-voice, unquestionable plan of action mainly focused to favor the few elite while ignoring the welfare of the rest of population. From the 1800s to the end of the 20th century, as presidential administration came and went, the forms of government has been described as authoritarian, semi-democracy, centralized government, untouchable presidencies, mass-controlling, corporatist and elite-controlled.[80] As each administration took turn, some changes have occurred, sometimes as to contribute to the welfare of the least fortunate but, overall, the political framework behind the economic and social structure of the country continues to be the greatest contributor to inequality.[81]

Foreign trade policies and foreign dependence

While the NAFTA agreement proved effective in increasing Mexico's economic performance, foreign trade policies have been heavily criticized by activists such as Michael Moore (in Awful Truth) as not doing enough to promote social advancement and reducing poverty.[81] To remain competitive in the international market, Mexico has had to offer low wages to its workers while allowing high returns and generous concessions to international corporations.[82] The words "palancas" and "favores" are part of Mexican economic culture where high-ranking policy makers and private entrepreneurs are accused of promoting their own bottom line while ignoring the necessaries of the working class.[83]

Current recessionary trends in the United States have an even greater impact on Mexico because of the great economic dependence on the northern neighbor. After crude oil export sales, remittances sent home by Mexicans working in the United States are Mexico's second largest source of foreign income.[84][85]

Government efforts and economic policies

Administration after administration, economic policies and social development programs have been targeted at decreasing poverty and increasing development in the country. Even with the best of intentions, friction between the "special interests" of decision-makers and the general public welfare, makes it difficult for clear goals in the benefit of the public to be accomplished.[86]

Cancun is an example of where the government have failed to promote general welfare and unequal distribution of wealth. While known for its crispy white beaches, fancy hotels of international renown, and spring break; Cancun shows a notorious economical inequality between the touristic urban zones, and its more rural outskirts, where in various cases, the poorest neighborhoods lack one or more basic services.[87][88]

Transparency and corruption

The lack of political transparency in Mexico has led to bureaucratic corruption, market inefficiencies, and income inequalities.[89][90][91] The ability to exercise civil rights has been increasingly displaced by the control of official authorities, including access to vital information that can capture the misappropriation and mis-allocation of funds, and public participation in state and municipal-level decision-making.[92] This opens up a channel for corruption. Evidence of this can be derived from the Corruption Perception Index 2010: Mexico received a low score of 3.1, on a scale of 0 to 10 (lower scores represent higher levels of corruption).[93] The result is a diffusion of corruption, from the state to the municipal level, and even right down to local security.[94][95]

While it can be difficult to quantify the costs of corruption with pinpoint accuracy, a report from the UN estimates that the cost is about 15 percent of Mexico's GNP, and 9 percent of its GDP.[96][97] Such higher costs have adversely affected the growth of the economy, for instance deterring foreign investments due to uncertainty and risk. A study by Pricewaterhouse Coopers reveals that Mexico had lost $8.5 billion in foreign direct investments in 1999 due to corruption.[98] Business companies admit to spend as much as 10 percent of their revenue in bureaucratic bribes.[97] 39 percent is spent on bribing high-ranking policy makers and 61 percent on lower-ranking bureaucratic-administrative office holders.[99] At least 30 percent of all public spending ends up in the pockets of the corrupt.[99]

Even the domestic impact of corruption is no less severe, incurring additional expenses on firms and households. A family on average pays 109.50 pesos as bribes to authorities; households have also reported paying up to 6.9 percent of their income as bribes. In total, the cost of corruption in terms of GDP was estimated to be about $550bn in 2000.[100]

The situation is still problematic in spite of recent initiatives by the state to become more transparent to the public.[101] Over the years, there has been an effort by the government to reduce opacity, but even so, these initiatives often do not realize their full potential. In June 2003, under Vincente Fox's presidency, the implementation of the Federal Law of Transparency and Access to Public Government Information (IFAI) offered civic organizations and members of the public to acquire previously undisclosed information. This reform has led to the exposure of previous under-the-radar activities, such as the government's misappropriation of 200 million pesos that was intended to combat AIDS.[102] And yet, censorship is still prevalent: in 2008, changes were proposed to increase the subjugation of IFAI's decisions to state control, so that the distribution of information would become more centralized.[103] A number of vertical subversions were also carried out at the time, including the merging of offices that handled information requests with less important agencies.[104] This violated the earlier progressive changes to the constitution, including Article 6, so that transparency was threatened.

Opacity is therefore a major player as a determinant of inequality, especially in effecting the welfare of lower-class households.[105] When resources are misallocated and official funds pocketed by illegitimate parties, the true quality of public services such as healthcare tend to be lower than expected;[106] similarly, the secrecy of the government's budget allocation prevents public scrutiny, so it is difficult to establish financial accountability.[107] As well, from a broader perspective, vital infrastructure from projects, especially those aimed at facilitating social mobility, will also have to deal with the potential impediments caused by the overpricing effect and unnecessary risks of corruption, thereby reducing the accessibility of infrastructure for the poor, especially in rural areas where such infrastructure is less established than in urban areas.[108]

Government and politics (social programs)

Mexico is a country that has significantly improved in various areas such as access to health, education, life expectancy, GDP, level of exports abroad, infrastructure, labor productivity, among others.[109] But it should also be noted that the distribution of income has become increasingly unequal; which is a serious problem because the misallocation and generation of resources inhibits economic competition in societies, leaving important groups of the population without the possibility of really competing in the economic sphere, which is one of the main obstacles to defeat and eradicate poverty of any kind.

The first time that a social program of collective and voluntary cooperation was launched was under the mandate of Carlos Salinas de Gortari and it was known as the National Solidarity Program (PRONASOL),[110] this had as its main banner to combat conditions of extreme poverty and meet their basic needs, this program sought to foster cooperation through unpaid effort.

In other words, the government provided goods and inputs to citizens, so that through their efforts and work, they would create the necessary conditions to progress and get out, with government help, from the condition of poverty. At the beginning, this program was highly questioned due to its clientelist utility. For example, there is a record that in the places where it entered with the greatest rigor and resources was in those localities in which the electoral results did not favor that president.[110]

PRONASOL[110] covered different axes among which were the immediate improvement in living standards, in which the government gave direct government transfers to beneficiaries; solidarity for production, in which employment opportunities and development of productive capacities and resources were offered (investing, generating and developing human capital); solidarity for regional development, where infrastructure works of regional impact were built and development programs were carried out in specific regions (generating infrastructure by regions, employing local people).

This innovative social program achieved a downward conception of poverty rates in the country, and it was also considered a pioneer in the field to such a degree that different countries in Latin America adopted it as the main social policy against poverty. PRONASOL[110] was very well received by Mexican society because it allowed them to observe results and perceive an economic improvement in the very short term, since it was based on a huge amount of government direct transfers.

Also, its success was based on the improvement and development of human capital; this was evident when, for example, in rural communities the government gave away corn or different seeds so that people[110] (laborers and farmers) could work them and obtain financial and personal benefits from them; Another example is the provision of construction material for people with limited resources, to build a decent home, or if it already exists, to improve it.

It is important to note that before 2000,[3] there wasn't an official measurement of poverty in Mexico, so it is not possible to speak of concrete figures on poverty prior to this year (all were approximations). It is known that given the distribution of money and direct government transfers to the people benefited by these programs, the situation of many improved, but we do not know for sure aggregate figures. After this year, during 2001 and 2002, SEDESOL[111] produced the first official income-based poverty measurement.

It was not until the end of 2005 that CONEVAL[3] was created, with the main task of measuring poverty, a mission that it carried out on a specific basis until 2009.

Reducing poverty

Poverty aid organizations and social development groups have remained active in Mexico. Despite foreign and national aid programs in the country, the overall level of poverty in the country prevails.[112]

Concerning the last two six-year terms of Mexican former presidents, it is important to highlight that the poverty figures were slowly decreasing. For example, according to CONEVAL numbers, in 2010 46.1%[3] of the Mexican population was poor, however in the years up to 2016 this figure dropped to 43.6%.[3]

In addition, during that time 3 million Mexicans were removed from extreme poverty,[111] having gone from 11.3% of Mexicans living in extreme poverty to 7%.[109] One of the main criticisms made of the previous six-year term is that it did indeed reduce the number of people in extreme poverty, but the number of people in moderate poverty increased in a greater proportion.[3]

A public policy to combat the lack of food was the community kitchens implemented during the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, which succeeded in decreasing food poverty levels. [109] The community kitchens program sought to improve the nutritional conditions of the population regarding boys and girls from 1 to 11 years of age, pregnant and lactating women, people with disabilities and adults over 65 years of age.[109]

Government approach

- In 1997, the Mexican government launched PROGRESA (Spanish: Programa de Educación, Salud y Alimentación), an integrated approach to poverty alleviation through the development of human capital.[113]

- In 2002, the Social Development Secretary (SEDESOL) replaced PROGRESA with Oportunidades (English: Opportunities); extending coverage to the urban poor and aiding high school students.[114]

Transparency Collective

The Transparency Collective, or El Colectivo por la Transparencia in Spanish, is a non-governmental collective organization that advocates transparency in Mexico. It was first formed by six civil society organizations in 2002 to demand for greater transparency from state agencies, and the right to access information. Currently, it consists of eleven civil society groups with the common goal of strengthening democracy and raising accountability and the transparency of the state.[115] The Transparency Collective offers an avenue for locals to seek help in obtaining the right to information by offering manuals and online tutorials teaching the locals how to file a request for information. It also discusses topics like human rights, the legislature and government budgets so that locals will be more informed and aware of their rights.[116] For example, Fundar, an NGO which specializes in government budget analysis, runs workshops to educate the public on disseminating information released by government agencies.[117]

The Transparency Collective has also been working with IFAI (Federal Institute of Access to Information). The civil society was productively engaged in the reform of the constitution. For example, CIDE, an academic focusing on public policy, worked at state level helping states comply with the reform. Fundar also focused on evaluating government responses to information requests, the appeals process and on training groups to analyze information released by the government.[118]

Despite the organizational size of the Transparency Collective, collectivization has nonetheless been an important factor in its effectiveness. The collective call for greater transparency was one of the reasons for the comprehensive reform of Article 6 of the Mexican constitution in 2007, which heralded a new level of progression for Mexico's right-to-know movement.[119] The reforms guaranteed the public's rights to non-confidential information at all levels of the government. State transparency laws also had to be standardized around certain basic principles within a year, and states had to implement electronic information systems.[119]

However, in spite of this, there is still a considerable way to go to achieve full transparency. The 2008 constitutional amendments, and interference of the judiciary branch with the demanded disclosure of tax information, threatened the FOI laws that were previously established. Nevertheless, this movement has been met with fierce protests from civil society groups,[120][121] and the Collective continues to appeal to the government to allow for more civil participation.[122]

Demographics

- Mexico's wealth is unevenly distributed among its people where 10 percent of nation's wealthiest have 42.2 percent of all income and 10 percent of the nation's poorest have 1.3 of the remaining income.[67]

- 53.4 percent of the rural population and 36.2 percent of the urban population has education below the 7th grade. 18.9 percent of the rural population and 8.9 percent of the urban population lacks any form of formal education.[123]

- Current figures estimate that at least 44.2 percent of the population lives under poverty. Of those, 33.7 live under a moderate state of poverty and at least 10.5 percent live under extreme poverty.[124]

- States with highest human development: Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Federal District, Nuevo León, Quintana Roo, Sinaloa, Sonora, and Tamaulipas.[125]

- States with lowest human development: Chiapas, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, and Zacatecas.[125]

World comparison

*The next comparisons are done between national poverty lines, meaning that each country has a different criteria to set its poverty line, for a comparison among countries under the same criteria see International poverty line

- Mexico is the second largest economy in Latin America, after Brazil; and the second Latin American country with most number of poor, after Brazil as well; given Mexico's population is about 80 million less than Brazil.[126][127]

- Mexico has the 11th to 13th richest economy in the world and ranks 4th with most number of poor among richest economies.[128][129]

- Mexico is the 10th to 13th country with the most number of poor in the world.[130]

- Of the ten countries with greater population, Mexico ranks 8th as nation with most number of poor behind the People's Republic of China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Bangladesh.[131]

- Of 193 United Nations members, at least 113 nations show higher levels of poverty and decreased social development and at least 55 other nations have less poverty and higher social development.[132]

- Mexico ranks 56th among most developed of the world's nations.[132] It ranks 4th as most developed of Latin American countries, behind Chile.[132]

Poverty and indigenous communities

Indigenous communities suffer particularly from poverty, causing them to be marginalized from society. Although "local and federal governments implemented social protection programs so as to alleviate poverty conditions and interregional disparities, in general, conditions for indigenous people remain unchanged," (Gonzales cited World Bank, 2005). Studies have shown that ethnicity is an important cause for inequality in income distribution, access to basic health care services and education, which in turn explain the significant difference in earnings between indigenous and non-indigenous people. According to the World Bank, about three-quarters of indigenous peoples in Mexico are poor and the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous groups is very high; the difference in poverty has been divided into explained and unexplained components. The explained components are "the amount of the gap attributed to observable characteristics such as education, age, occupation, region of residence and so on," (World Bank, 2005) which account for three quarters of poverty. The unexplained components are related to the level of discrimination and explain a quarter of the poverty. Indigenous people in Mexico are faced to significant disadvantages in economic and social outcomes and although discrimination against them appears to be decreasing, the government needs to improve education and government services to reduce the poverty gap. Based on their research, the World Bank suggests the promotion of equal health care access for indigenous peoples "though the implementation of a head start program that focuses on maternal and child health issues," (World Bank, 2005) as well as improving "data collection efforts related to identifying indigenous populations," (World Bank, 2005) to better monitor progress over time.

References

- "Mexico - New Global Poverty Estimates". World Bank.

- Mexican Congress (4 January 2004). "Mexican Congress Bill, General Law of Social Development" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "CONEVAL Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social | CONEVAL". www.coneval.org.mx. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- "1.4 millones de mexicanos dejan la pobreza extrema entre 2010 y 2012". Animal político. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- "Clases medias en México" (PDF). INEGI. 12 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "La medición oficial de la pobreza en México". EstePaís.com. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "Cruzada contra el hambre atenderá a 7.4 millones de pobres". Milenio. 21 January 2013. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- George H. Wittman (9 July 2010). "Mexico Unmasked". The American Spectator. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- TheCatalist (17 March 2010). "Mexico 2050: The World´s Fifth Largest Economy". Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- IMF Survey (16 March 2010). "Mexico Recovering..." International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Impact of Globalization: the Case of Mexico" (PDF). HumanGlobalization.org. November 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Tal Barak Harif & Jonathan J. Levin (4 October 2010). "Mexico Boom Leads Americas as Drug War Loses to NAFTA". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Brazil now Latin America's largest economy". NBC News. Associated Press. 30 September 2005. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- Samuel Peña Guzman (4 September 2006). "Social Inequality in Mexico". Mexidata.info. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Federal Government Poverty Fight Initiative". Notimex. 28 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Mexico achieves universal health coverage, enrolls 52.6 million people in less than a decade". Harvard School of Public Health. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- "Politics, Poverty, and Corruption in 20th-Century Mexico". Documents for Small Business and Professionals. 1 November 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Erika Wurst (8 December 2004). "Mexican Middle Class Rising". Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication-Arizona State University. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- José Enrique Vallarta Rodríguez (18 February 2008). "Unemployment and Mexico's Need to Create More Jobs". MexiData.info. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Mexico. Events of 2017. 5 January 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - BookRags Student Essays (2006). Causes for the Mexican Revolution. BookRags, Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- World Bank-World Development Indicators (2000). "Mexico-Poverty and Wealth". Encyclopedia of Nations. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Mexican National Income Survey and Household Expendetures (2008). "Mexico Average Salaries & Expenditures". World Salaries. Org. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Notimex/El Universal (3 February 2008). "12% of Active Work Population earns Minimum Daily Wages". El Universal. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- The World Bank (27 August 2005). "Mexico's Urban Poor Work Harder For Less". CityMayorsSociety. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Liliam Flores O. Rodriguez (7 October 2009). "History of Social Development in Mexico, (in Spanish)". Mexican Congress-Chamber of Deputies. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Mexican Congress (20 December 1997). "Constitution of Mexico, Title 1: Chapter I, articles 3 and 4, Title VI: Article 123". Illinois State University. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Library of Congress Country Studies; CIA World Factbook (10 November 2004). "Mexico and the Great Depression". Photius Coutsoukis. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carlos Cruz Pacheco (11 October 2010). "Poverty in Mexico: Same as in 1992, PRI". ArgonMexico.com. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- El Mundo de Tehuacán (17 October 2010). "Imprisoned in Poverty". Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Exploring Mexico Editorial Group (2010). "The Poorest States of Mexico". Explorando México. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- John P. Schmal (2004). "History of Mexico: Chiapas-Forever Indigenous". Houston Institute for Culture. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- World Bank Group & Guanajuato's State Population Council (November 2003). "Migration and Poverty in Mexico's Southern States" (PDF). Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Carlos A. Benito (May 2000). "The Causes of Poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Role of Political Institutions and Governance" (PDF). Sonoma State University-Economics Department. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Suárez del Real Islas, Aline (2019). "Los problemas sociales más graves en México". La Guía Femenina.

- James Chyper (1 February 2002). "Poverty in Mexico" (PDF). Red Eurolatinoamericana Celso Furtado. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Suzanne Bilello (1989). "The Economic Chaos In Mexico: A Primer". Alicia Patterson Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 April 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Hari Srinivas (16 August 2010). "Causes of Poverty". Global Development Research Center. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Kevin Rolwing (June 2006). "Education in Mexico". World Education Services. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "Mexico's Education System Ranks Last Among Members of OECD". SourceMex Economic News & Analysis on Mexico. 22 September 2004. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Aileen Garcia; Prof. Eugene Matusov (28 April 2006). "Life In Mexico:Focusing on Schools". University of Delaware-Publishing Web for Student’s Final Paper. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Nurit Martínez (18 January 2010). "(Spanish)700 mil dejan la escuela por crisis". El Universal. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Mexican Editorial Organization (7 October 2008). "(Spanish)En el 73% de las familias en México hay rezago educativo". Tabasco Herald. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "El PNUD en México". UNDP (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- "Mexico Faces Up to Unemployment Growth". Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. 21 September 2005. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Prof. Héctor Ramón González Cuellar (Tijuana Technological Institute) (2010). "Social Conflict: Brains Escape..." ZETA Newspaper. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Barahona, Igor (January 2018). "Poverty in Mexico: Its relationship to social and cultural indicators". Social Indicators Research. 135 (2): 599–627. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1510-3. S2CID 157276508.

- Basham, Ringe y Correa, S.C. (2005). "Age Discrimination Internationally-Mexico". Lewis Silkin, LLP. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sara Arellano (19 August 2009). "(Spanish) Discriminación por edad se dispara en mercado laboral". El Universal Newspaper. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Lic. Gilberto Rincón Gallardo. "(Spanish)Disability in Mexico" (PDF). Mexican Senate. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Pedro Moreno, Silvia Tamez & Claudia Ortiz (2002). "Social Security in Mexico" (PDF). Solidarity Center and Autonomous Metropolitan University-Xochimilco (UAMX). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Sara María Ochoa León (June 2005). "Unemployment Insurance in Mexico" (PDF). Center of Social Studies and Public Opinion, Mexican Congress-Chamber of Deputies. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- World Bank. "A Study of Rural Poverty in Mexico" (PDF). Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Anna Wellenstein; Angélica Núñez & Luis Andrés (2005). "Social Infrastructure" (PDF). The World Bank. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Laura M. Norman; Jean Parcher & Alven H. Lam (12 December 2004). "Monitoring Colonias Along the U.S.-Mexico Border" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey and Association of American Geographers. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- "Violence and crime in Mexico at the crossroads of misgovernance, poverty and inequality". World Bank Group. April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Engineer Arturo M. Monforte Ocampo (November 2008). "Conserving the Toll-Free Federal Highways" (PDF). Engineering Academy, A.C. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Isabel Becerril (27 October 2010). "Badly Needed National Urban Development Policy". El Financiero. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Oyuki Sànchez (12 October 2010). "Urban and Housing Planning: Fundamental for Development". CentroUrbano.com. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Jesús Orozco Castellanos (4 August 2008). "Marginalization and Inequality in Mexico". Crisol Plural. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Blanca Valadez (9 August 2010). "In Extreme Poverty 39% of Indigenous in Mexico". Fundación Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung México. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- The World FactBook (9 November 2010). "Mexico's Profile". CIA. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Mexico Faces Up to Unemployment Growth". Universia. 21 September 2005. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Gustavo Merino (7 May 2008). "Social Policy and Job Creation in Mexico". Social Development Secretariat (SEDESOL). Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- International Energy Statistics (June 2010). "Oil and Energy in Mexico". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- José Enrique Vallarta Rodríguez (12 February 2007). "...Needed Labor Reform in Mexico". MexiData.info. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- United Nations (27 March 2010). "Gap between rich and poor in Latinamerica is largest in the world, says UN". MercoPress. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- The Week (16 March 2010). "7 things to know about Carlos Slim Helu". Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Rodrigo Garcia-Verdú (20 August 2008). "(Spanish) Wealth of the Nation". Semanario de Economía y Finanzas. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Gordon H. Hanson (October 2004). "Globalization, Labor Income, and Poverty in Mexico" (PDF). University of California, San Diego (UCSD)-National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Gerardo Esquivel (December 2008). "The Dynamics of Income Inequality in Mexico since NAFTA" (PDF). Harvard University-Center for International Development. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Alejandro Tuirán Gutiérrez (December 2005). "(Spanish) Inequality in Income Distribution in Mexico" (PDF). National Population Council (CONAPO). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- José Enrique Vallarta Rodríguez (26 March 2007). "What Are The Most Serious Problems Mexico Faces?". MexiData.info. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Allan Wall (21 May 2007). "World Bank Diagnoses Mexican Economic Problems". WorldBankd-MexiData.info. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Elizabeth Malkin (2 June 2009). "Are Monopolies Holding Mexico Back?". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Allan Wall (25 February 2008). "Pemex, Mexico's Oil & Gas Monopoly, Must be Modernized". MexiData.info. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Emir Olivares Alonso (15 May 2007). "(Spanish) To Grow Mexico Must Eliminate Powerful Monopolies". La Jornada. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- "(Spanish) Bureaucracy- Parking Brake for Competitiveness in Mexico". EL Informador. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Murilo Kuschick Ramos (1 February 2002). "(Spanish) Government, Poverty, and Public Opinion". Autonomous Metropolitan University, Azcapotzalco (UAM). Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Mara Steffan (22 October 2007). "The Political Impact of NAFTA on the Mexican Transition to Democracy, 1988-2000". Bologna Center Journal of International Affairs-Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Julia Hanna (19 July 2006). "Political Turmoil and Mexico's Economy". Harvard University-Business School. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Gordon H. Hanson; Ann Harrison (January 1999). "Trade liberalization and wage inequality in Mexico". New York State School of Industrial & Labor Relations. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Ricardo Bonilla Esparza (29 November 2006). "(Spanish) Corruption a Part of Mexican Culture". El Siglo de Durango. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Tracy Wilkinson (2 June 2009). "Remittances to Mexico down sharply". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- "Mexico Sees Record Drop in Remittances". CBS News. Associated Press. 27 January 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Sergey V. Mityakov (10 June 2010). "Special Interests and Financial Liberalization: the Case of Mexico". Economics & Politics. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 23: 1–35. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0343.2010.00368.x. S2CID 152474042.

- Marc Cooper (6 September 2003). "The Real Cancun: Behind Globalization's Glitz". The Nation. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Ali Tonak & Tessa Brudevold-Iversen (17 October 2005). "The Real Cancun". Upside Down World. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Harry Kimball (30 December 2008). "Corruption in Mexico is Rampant and Pervasive". Newser. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Daniel C. Levy; Kathleen Bruhl & Emilio Zebadúa (24 September 2001). Mexico: The Struggle for Democratic Development. University of California Press. ISBN 0520228316.

- Revenue Watch Institute. "Mexico: Transparency Snapshot". Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Rosy Laura Castellanos (2005). "(Spanish) Accountability, access to information and transparency in Mexico" (PDF). Civic Alliance, AC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Transparency International Latinoamerica y el Caribe (26 October 2010). "Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 Results". Transparency International. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Prof. Claudio Lomnitz (27 November 1995). "Understanding history of corruption in Mexico". University of Chicago-Chicago Chronicle. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- BBC News (30 August 2010). "Mexico sacks 10% of police force in corruption probe". BBC News. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Jacques Hallak & Muriel Poisson (2007). "Corrupt schools, corrupt universities: What can be done?" (PDF). International Institute for Educational Planning. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Julio Reyna Quiróz (13 April 2010). "(Spanish)The Cost of Corruption in Mexico..." World Economic Forum. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- PBS.org (5 September 2002). "How Big is Mexico's Problem?". PBS. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Ronén Waisser (7 October 2002). "(Spanish) Cost of Corruption in Mexico". Monterrey Technological-Center of Strategic Studies. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- PBS.org (5 September 2002). "How Big is Mexico's Problem?". PBS. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Rocio Moreno Lopez. "The Lack Of Transparency And Accountability Mechanisms For Mexico's Oil Income" (PDF). Economic Policy Mexico’s Rights-To –Reforms Civil Rights Perspective. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Lost in Transition: Bold Ambitions, Limited Results for Human Rights Under Fox. New York: Human Rights Watch. 2006. ISBN 1-56432-337-4. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- FUNDAR.org (28 May 2010). "(Spanish) Press Release: The opacity is gaining ground in Mexico" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Zachary Bookman (22 April 2008). "Shine a Light on Mexico". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Sanjeev Gupta; Hamid Davoodi; Rosa Alonso-Terme (May 1998). "Does Corruption Affect Income Inequality and Poverty?" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- George W. Grayson (19 November 2009). "Health care and illegal immigrants in America: why Mexico is the key". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- David Davia Estefan & Jorge Romero Leon. "Legislators in the Labyrinth: Discretion and Opacity in the Policy Debate over Mexico's Budget" (PDF). Economic Policy Mexico’s Rights-to-Know Reforms Civil Society Perspectives. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Transparency International. "Preventing Corruption on Construction Projects". Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "Datos Abiertos de México - Instituciones". datos.gob.mx. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- "México: conoce usted el Pronasol?". unesdoc.unesco.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- Adultos, Instituto Nacional para la Educación de los. "Secretaría de Desarrollo Social". gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- Jorge Cisnero (28 July 2004). "(Spanish) Poverty in Mexico: an Evaluation of Conditions, Trends, and Government Strategy". World Bank. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Leigh Gantner (8 November 2007). "PROGRESA: An Integrated Approach to Poverty Alleviation in Mexico". Cornell University Library. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Warren Olney (1 January 2009). "Mexico's anti-poverty program, Oportunidades". Public Radio International. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- "(Spanish) Strategic Planning for the Transparency Collective" (PDF). El Colectiva por la Transparencia. 8 February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "(Spanish) Accountability, Access to Information and Transparency in Civil Society Organizations" (PDF). El Colectiva por la Transparencia. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "The Mexico Freedom of Information Program". George Washington University. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Benjamin F. Bogado; Emilene Martinez-Morales; Bethany D. Noll & Kyle Bell (December 2007). "The Federal Institute For Access to Information & A Culture of Transparency (A Followup Report)" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "Mexico's Constitutional Reform Guarantees the Right to Know". George Washington University. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "(Spanish) Transparency in Quaretaro" (PDF). El Colectivo por la Transparencia. 10 December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "Denouncing Changes to Transparency and Access to Information in Queretaro" (PDF). El Colectivo por la Transparencia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "(Spanish) The Autonomy of IFAI in the Hands of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation" (PDF). El Colectivo por la Transparencia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Caribbean and Latin American Economic Commission (CEPAL) (24 January 2009). "(Spanish) Primary Education Would Reduce Hunger". Milenio. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- CONEVAL (2009). "CONEVAL's 2009 Fact Sheet" (PDF). U.S. Embassy in Mexico City. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- United Nations Development Programme-Mexico (October 2010). "HDI in Mexico; pg. 41" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Agencia EFE (19 July 2009). "(Spanish)Mexico with more than 50 Million Poor". El Expectador. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Considering Mexico has the second biggest population in Latin America and 49-50+ million in poverty-- Brazil has over 57 million in poverty-- the result is Mexico with second highest number of poor in the Western Hemisphere.

- CIA World FactBook (9 November 2010). "2010 GDP Comparison Chart". Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Only China, India and Brazil have a higher number of people in poverty than Mexico among nations with higher GDP than Mexico.

- By analyzing nations' poverty rates and their populations: Mexico's 2010 estimate at 111,212,000 and 44.2 rate of poverty from 2009 CONEVAL's study.

- By analyzing nations with greater population than Mexico and their poverty rates.

- United Nations Development Programme (4 November 2010). "2010 Human Development Index; pgs. 142-146". UNDP.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)

Further reading

- Kevin J. Middlebrook and Eduardo Zepeda (2003), Confronting Development, Stanford University Press - Assessing Mexico's Economic and Social Policy Challenges.

- Daniel Hernández Franco, Cristina Barberena Rioseco, José Ángel Camacho Prudente, Hadid Vera Llamas (2003) Desnutrición Infantil y Pobreza en México, Secretariat of Social Development(SEDESOL) - Study on child malnutrition and poverty in Mexico.

- Gordon H. Hanson (2005), Globalization, Labor Income, and Poverty in Mexico, National Bureau of Economic Research - Study on globalization and how it affected income and poverty in Mexico.

- Luis Vega Martínez (2005), La Pobreza en México, UNAM - University professor's views and thoughts on poverty in Mexico.

- Gabriela Pérez Yarahuán (2007), Social Development Policy, Expenditures and Electoral Incentives in Mexico, Universidad Iberoamericana-Ciudad de México - Discussions and theories on social development policy in Mexico from 1990s and onward.

- Francis Fukuyama (2008), Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap Between Latin America and the United States, Oxford University Press - Collection of essays discussing reasons for development gap between the United States and Latin America.

- Darcy Victor Tetreault. The Evolution of Poverty in Late 20th-Century Mexico. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d'études du développement Vol. 27, Iss. 3, 2011

External links

- CONEVAL- Government Agency in charge of Social Development Studies Archived 2014-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- United Nations Development Programme in Mexico

- Transparency International in the Americas

- Fondo España-PNUD in Latin America and Caribbean - attempts to promote social development policies.