Angel Island Immigration Station

Angel Island Immigration Station was an immigration station in San Francisco Bay which operated from January 21, 1910, to November 5, 1940,[4] where immigrants entering the United States were detained and interrogated. Angel Island is an island in San Francisco Bay. It is currently a State Park administered by California State Parks and a California Historical Landmark. The island was originally a fishing and hunting site for Coastal Miwok Indians, then it was a haven for Spanish explorer Juan Manuel de Ayala. Later, it was developed as a cattle ranch, then, starting with the Civil War, the island served as a U.S. Army post. During the island's Immigration Station period, the island held hundreds of thousands of immigrants, the majority from China, Japan, India, Mexico and the Philippines. The detention facility was considered ideal because of its isolated location, making it very easy to control immigrants, contain outbreaks of disease, and enforce the new immigration laws.[5] The station is listed on the National Register of Historic Places under the title Angel Island, U.S. Immigration Station, and is a National Historic Landmark. The station is open to the public as a museum – "a place for reflection and discovery of our shared history as a nation of immigrants".[6]

Angel Island | |

Angel Island Dormitory | |

| |

| Nearest city | Tiburon, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37.8697°N 122.4260°W |

| Area | 20 acres (8.1 ha)[1] |

| Built | started 1905; opened 1910 |

| Architect | Walter J. Mathews[1] |

| Architectural style | Mission/Spanish Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000164[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 14, 1971 |

| Designated NHLD | December 9, 1997[3] |

History

In 1850, President Fillmore declared Angel Island, the second largest island in San Francisco Bay, to be a military reserve. Indeed, during the Civil War, the island was fortified to defend San Francisco Bay from possible attack by Confederate forces. In the 19th century, new arrivals to the U.S. entering at the Port of San Francisco were housed and processed in quarters located at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company docks on the San Francisco waterfront. After the quarters at the docks proved inadequate and unsanitary, a study, authorized in 1904, recommended building a new immigration station on the isolated and nearby Angel Island. In 1905, the War Department transferred 20 acres of land on the north shore of the island, facing away from San Francisco, to the Department of Labor and Commerce as the site for the new immigration station. Architect Walter J. Mathews designed the station compound to include an enclosed detention center with an outdoor area and guard tower as well as an administration building, hospital, powerhouse and wharf, which was later known as China Cove.[1]

Angel Island Immigration Station, sometimes known as "Ellis Island of the West," began construction in 1905 and opened January 21, 1910. Construction of the facility involved leveling a former Coast Miwok village site and shell mound, including the interred remains of numerous people.[7] The main difference between Ellis Island and Angel Island was that the majority of the immigrants that traveled through Angel Island were from Asian countries, such as China, Japan, and India. The facility was created to monitor the flow of Chinese immigrants entering the country after the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The Act only allowed entrance to merchants, clergy, diplomats, teachers, and students, barring laborers.[5]

At Ellis Island, only between one and three percent of all arriving immigrants were rejected; at Angel Island, the number was about 18%.[8] The Chinese were targeted due to the large influx of immigrants that were arriving in the United States. Chinese immigrants were seen as a threat because they occupied low-wage jobs, and after the economic downturn during the 1870s, Americans experienced serious unemployment problems. This resulted in increased discrimination against the Chinese, who were labeled as unsuitable due to their appearance and social status. The detention center was opened in 1910, after a series of laws were enacted which significantly restricted Chinese immigration. Immigrants arrived from 84 countries, with Chinese immigrants accounting for the largest ethnic group to enter San Francisco until 1915, when Japanese immigrants outnumbered the Chinese for the first time.[5]

1910–1940: Process

The length of time immigrants spent detained varied depending on how long the interrogation process lasted. For some it was only a few days and for others it lasted for months, the longest recorded stay being 22 months.[9] This was significantly different from Ellis Island, which had more relaxed regulation and allowed many immigrants to enter the United States on the day of their arrival. Interrogations were extended because of the racial discrimination against Asians that was prevalent at the time. Chinese immigrants, mostly males, claimed to be sons of Chinese individuals who were American citizens, in response to the Chinese Exclusion Act. Since children of citizens are also considered U.S. citizens, regardless of where they are born, it is illegal to deny them entry if they can prove their familial relationship. Immigrants falsely claiming familial ties became known as "paper sons" or "paper daughters". Some American citizens of Chinese descent participated in immigration fraud as purported parents in return for money, or to help other people of the same ethnicity.[5]

As a result, an extensive and grueling interrogation process was made to weed out the people for making fraudulent claims. The applicant would then be called before a Board of Special Inquiry, composed of two immigrant inspectors, a stenographer, and, if needed, a translator. Over the course of a few hours or days, the individual would be grilled with specific questions that only the real applicants would know about, for instance, their family history, location of the village, their homes and so on. However, a way around these questions was preparing them months in advance with their sponsors and memorizing the answers. To ensure that the applicant was telling the truth, witnesses from the United States, who were often other family members, were called in to corroborate the applicants story. The "family members" sometimes lived across the country, which extended the process, since their testimony had to be verified before proceeding. If there was any doubt that the applicant was lying, the questioning process was prolonged. If deviation was suspected from the testimony presented by the witnesses, the applicant and the rest of the family would be in jeopardy of deportation.[10]

Some applicants appealed the decision of the Board, resulting in a prolonged stay at the detention center because the appeal process was long and tedious. Additionally, the length of stay varied depending on what country the individual was coming from. Japanese immigrants often held documentation from government officials that expedited the process of entering the country. This resulted in the majority of detainees being Chinese since they had no alternative but to endure the questioning. Since the goal of Angel Island was to deport as many Chinese immigrants as possible, the whole process was much more intrusive and demanding for the Chinese compared to other applicants.[10]

After 1940

The detention center was in operation for thirty years; however, there were many concerns about sanitation and for the safety of the immigrants at Angel Island. The safety concern was proved to be warranted when, in 1940, fire destroyed the administration building and women's quarters. As a result, all the immigrants were relocated to a landlocked facility in San Francisco and the former Immigration Station was returned to the U.S. Army. During World War II it served as a prisoner of war processing center. In 1943, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

After the war, the Army decommissioned the military installations, reduced its presence on the island, and left the former Immigration Station to deteriorate. It wasn't until 1963 that the island, including the detention facility, was converted to a state park. The buildings were set for demolition but were spared, after Ranger Alexander Weiss discovered Chinese poetry, partially obscured by layers of paint, carved in the wooden walls of the men's barrack in 1970.[11] "These poems carved into the walls remain as a memorial to all of those who passed through the island's harsh detention barracks on their journey to a new life in the U.S."[1]

Today, more than 200 poems have been recovered and restored, and all but the detention centers are currently available to the public.[10] Of the approximately one million immigrants who were processed at the Angel Island Immigration Station, roughly 175,000 were Chinese and 117,000 were Japanese. Between 75 and 82 percent entered America successfully.[9]

Immigrant perspectives

The predominantly Chinese immigrants who were detained at Angel Island were not welcomed in the United States. As recounted by one detained in 1940: "When we arrived, they locked us up like criminals in compartments like the cages at the zoo." Held in these "cages" for weeks, often months, individuals were subjected to rounds of long and stressful interrogations to assess the legitimacy of their immigration applications. Immigrants were made to recall minute details of their lives. On occasion, translators may have not have spoken the particular dialect of the immigrant competently; most Chinese immigrants were from southern China at that time, many spoke Cantonese. It was difficult to pass the interrogations, and cases were appealed many times over before one could leave the island and enter the United States. Often, successful immigrants produced elaborate instruction manuals that coached fellow detainees in passing interrogations; if anyone was caught with these manuals, they would most likely be deported. Those that failed these tests often feared the shame of returning to China, and some would commit suicide - either before leaving, or on the voyage back to their homeland.[12]

Many of the detainees turned to poetry as expression, spilling their emotions onto the very walls that contained them. Many of these poems were written in pencil and ink, or in brush, and then carved into the wooden walls or floors.[13] Some of the poems are bitter and angry, placid and contemplative, or even hopeful.

America has power, but not justice.

In prison, we were victimized as if we were guilty.

Given no opportunity to explain, it was really brutal.

I bow my head in reflection but there is nothing I can do.

Another example:

I thoroughly hate the barbarians because they do not respect justice.

They continually promulgate harsh laws to show off their prowess.

They oppress the overseas Chinese and also violate treaties.

They examine for hookworms and practice hundreds of despotic acts.

A more hopeful example:

Twice I have passed through the blue ocean, experienced the wind and dust of journey.

Confinement in the wooden building has pained me doubly.

With a weak country, we must all join together in urgent effort.

It depends on all of us together to roll back the wild wave.

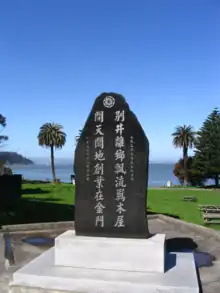

Monument

The Angel Island Chinese Monument (37°52′13″N 122°25′32″W) is a monument dedicated to Chinese immigrants who entered the United States through the immigration station.[14] It was completed in 1978 and placed in 1979.[15] The monument's inscription says "Leaving their homes and villages, they crossed the ocean only to endure confinement in these barracks. Conquering frontiers and barriers, they pioneered a new life by the Golden Gate."[14] The inscription is reminiscent of Chinese poems that were carved into the barracks walls of the immigration station by detained Chinese immigrants.[16]

See also

- California Alien Land Law of 1913

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (McCarran-Walter Act)

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

- Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986

- Immigration Act of 1990

- Paper Sons

- Tye Leung Schulze; the first Chinese American civil servant in the United States, who worked at Angel Island.

- Tyrus Wong, imprisoned on Angel Island when he was nine, he was later released and became the chief artist for Disney's Bambi.

- United States Immigration Station (Detroit, Michigan)

References

- "U.S. Immigration Station, Angel Island San Francisco Bay, California". nps.gov. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- California NHL List

- "The History of Angel Island: The Ellis Island of the West". San Francisco Travel. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- "United States Immigration Station (USIS)". angelisland.org. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- "A Place of Reflection and Discovery". Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- DeGeorgey, Alex (2016). "Contributions to San Francisco Bay prehistory : archaeological investigations at CA-MRN-44/H, Angel Island State Park, Marin County, California". Publications in Cultural Heritage (33): 5. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- Howard Markel and Alexandra Minna Stern, "Which Face? Whose Nation?" American Behavioral Scientist 42, no. 9 (June/July 1999): 1318; Roger Daniels, "No Lamps Were Lit for Them: Angel Island and the Historiography of Asian American Immigration," Journal of American Ethnic History 17, no. 1 (Fall 1997).

- Chow, Paul. "Angel Island" (PDF). americansall.com. Americans All. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- "Life on Angel Island". aiisf.org. Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- Nolte, Carl (October 24, 2014). "Alexander Weiss, ranger who preserved Angel Island poetry, dies". SF Gate.

Among Mr. Weiss' achievements were his discovery of and efforts to preserve discovered poetry carved into the walls by people detained at the Angel Island immigration station. Mr. Weiss was a state park ranger at the time and learned that the state planned to demolish some of the buildings at the immigration station because they were in poor repair. He learned that the walls were covered with poetry written in Chinese and Japanese by would-be immigrants and started an effort to preserve them. Mr. Weiss was characteristically modest about his effort. 'I just started the engine,' he said. 'Others drove the project'.

- Yu, Connie Young. "Rediscovered Voices: Chinese Immigrants and Angel Island." Amerasia Journal Vol. 4, No. 2 (1977), pp. 131.

- Lai, Him Mark, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung. Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island 1910-1940. Seattle: U of Washington, 1991. Print.

- "Angel Island Chinese Monument | Duke Migration Memorials". migrationmemorials.trinity.duke.edu. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Reconstruct and Illuminate: Advancing the Storytelling of Angel Island | Angel Island Immigration Station - San Francisco". AIISF. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Imprisoned Chinese Immigrants Etched Their Anguish Into Angel Island Walls". KQED. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

External links

- Angel Island State Park official website

- Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation - the non-profit partner of California State Parks and the National Park Service in the work to restore the historic immigration station at Angel Island.

- Angel Island Conservancy - Established in 1975, AIC’s primary mission is to facilitate the preservation, restoration and interpretation of historical and natural resources on Angel Island, with the goal of enhancing the visitors’ experiences and building a community to support AISP.

- U.S. Immigration Station Tours

- Early History of the California Coast, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Angel Island Company, State Parks concessionaire for tours, bike rentals, and catered picnics

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. CA-1841, "Camp Reynolds, Angel Island State Park, Angel Island, Marin County, CA", with 14 other entries for individual buildings

- Angel Island materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

- Angel Island-Tiburon Ferry