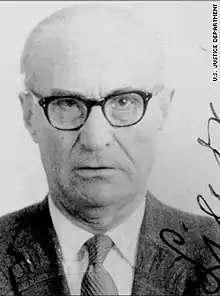

Aleksandras Lileikis

Aleksandras Lileikis (10 June 1907 – 26 September 2000) was the chief of the Lithuanian Security Police in Vilnius during the Nazi occupation of Lithuania and a perpetrator of the Holocaust in Lithuania. He signed documents handing at least 75 Jews in his control over to Ypatingasis būrys, a Lithuanian collaborationist death squad, and is suspected of responsibility in the murder of thousands of Lithuanian Jews. After the 1944 Soviet occupation of Lithuania, he fled to Germany as a displaced person. Refused permission to immigrate to the United States because of his Nazi past, he worked for the Central Intelligence Agency in the early 1950s. In 1955, his second application for permission to immigrate was granted and he settled in Norwood, Massachusetts, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1976. Eli Rosenbaum, an investigator for the Office of Special Investigations, uncovered evidence of Lileikis' war crimes; proceedings for his denaturalization were opened in 1994 and concluded with Lileikis being stripped of his United States citizenship. He returned to Lithuania, where he was charged with genocide in February 1998. It was the first Nazi war crimes prosecution in the post-Soviet block of Europe. He died of a heart attack in 2000 before a verdict was reached.

Aleksandras Lileikis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 June 1907 Paprūdžiai, Russian Empire |

| Died | 26 September 2000 (aged 93) Vilnius, Lithuania |

| Citizenship | Lithuania United States (1976–1996) |

| Alma mater | University of Lithuania |

| Organization | Lithuanian Security Police |

| Criminal status | Died before trial ended |

| Criminal charge | Genocide |

| Details | |

Span of crimes | 1941–1944[1] |

| Location(s) | Vilnius |

| Target(s) | Lithuanian Jews |

| Killed | At least 75 (suspected thousands) |

Early life

Aleksandras Lileikis was born on 10 June 1907 to a peasant family in Paprūdžiai in the present-day Kelmė District Municipality.[2] He attended the Žiburys gymnasium in Kražiai and War School in Kaunas.[3] In 1927, he began to study at the Faculty of Law at University of Lithuania.[1] He worked for the criminal police and later the State Security Department. In 1931–1934, he worked in the interrogation department and was the deputy of the security police chief in Marijampolė in 1934–1939. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1938.[3]

World War II

In 1939, when Lithuania gained Vilnius as a result of the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty, Lileikis became the deputy of the commander of the Vilnius district of the Lithuanian Security Police. He worked at suppressing the Polish resistance in Lithuania[4] and investigated the death of the Russian soldier Butayev, which was part of the official pretext for the Soviet ultimatum to Lithuania.[3] He fled to Germany in 1940 due to the Soviet occupation of Lithuania and applied for German citizenship in June 1941.[4]

In August 1941, after the German invasion of the Soviet Union and German occupation of Lithuania, he returned to Lithuania and reorganized the Lithuanian Security Police in Vilnius (about 130 men) on Gestapo lines according to instructions he received in Germany, complete with a special division (Komunistų-Žydų Skyrius) for dealing with "Jews and Communists". The Lithuanian Security Police had jurisdiction over Jews in hiding, non-Jews who helped Jews, and Jews suspected of Communist associations.[4] Usually, escaped or suspected Jews were arrested by the regular police and handed over to the security police for investigation and interrogation. The security police would then hand over the Jews to the German police or Ypatingasis būrys, a Lithuanian collaborationist death squad which murdered an estimated 70,000 Jews at nearby Ponary.[5][6] Acting as a desk murderer, Lileikis signed documents handing at least 75 Jews to Ypatingasis būrys.[7][8][9] Lileikis fully understood that the Jews would be murdered.[10] The Security Police also dealt with the Soviet partisans and Polish underground. For example, a report from 16 February to 21 March 1942 details that the security police in Vilnius arrested 319 people and 137 of them were sent to Ponary: 73 Jews, 23 Communists, 14 members of the Polish resistance, 20 document counterfeiters, and 7 spies. The duties related to non-Jewish groups increased as the number of Jews in the Vilna Ghetto dwindled and the anti-Nazi resistance grew.[6]

Eli Rosenbaum of the Office of Special Investigations (OSI), part of the Department of Justice, described Lileikis as "a senior-level perpetrator of the Holocaust". Neal Sher, former head of the OSI, stated that Lileikis "was as significant and probably more significant than someone like Klaus Barbie"—who was convicted of crimes against humanity in 1987—and "an instrumental cog in a wheel of mass destruction".[11] He is suspected of responsibility in the deaths of thousands to tens of thousands of Jews.[12]

CIA and immigration to the United States

After the Red Army invasion of Lithuania in 1944, Lileikis fled back to Germany and became a displaced person. In 1947, while living in a camp in Bamberg, he was investigated for war crimes by the United States Army Criminal Investigation Command, but the authorities had little documentation on war crimes in Lithuania. In 1950, Lileikis was unanimously refused permission to emigrate to the United States by the United States Displaced Persons Commission "because of [his] known Nazi sympathies"[13] and because he was "under the control of the Gestapo".[14] He was recruited for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1952 when he was living in Munich, described as a member of the Lithuanian National Union.[13] At the time of his recruitment, the CIA knew about his wartime activities and probable complicity in war crimes:[15] his file stated that he "was the chief of the political Lithuanian Security Police in Vilna during the German occupation and that he was possibly connected with the shooting of Jews in Vilna." But it nevertheless considered that there was "no derogatory information" on him,[14] and he was cleared for duty by the CIA headquarters on 5 March 1953.[13] Lileikis had little interest in spying and was instead interested in using his intelligence work to obtain permission to immigrate to the United States.[16] He was paid $1,700 (equivalent to $18,600 in 2022) annually for his work recruiting Lithuanians in East Germany and occasional translation and intelligence work,[14] but apparently was less than successful as the agency did not help him immigrate to the United States.[17] He may have helped other Lithuanian Nazi collaborators obtain CIA jobs or immigrate to the United States.[18] In 1995, the CIA claimed that "there was no evidence that this Agency was aware of his wartime activities". This statement was described as a "gross distortion" by journalist Eric Lichtblau.[19]

In 1955, he applied again for permission to immigrate to the United States. Although the CIA passed negative information to United States immigration authorities, his application was accepted without explanation.[20][15] Lileikis' deputy, Kazys Gimžauskas, and three other subordinates also immigrated to the United States.[20] He settled in Norwood, Massachusetts and became a naturalized citizen in 1976.[1][21] Lileikis was involved in the Lithuanian community in the United States; he attended a Lithuanian Catholic church and worked as an administrator for a Lithuanian encyclopedia company, as well as painting houses for a living. Although he could speak English, he preferred his native language.[22] Historian Timothy Naftali notes, "the presence of this mass murderer in the general population sent a signal to fellow veterans of the secret police in Nazi-occupied Lithuania that Cold War America was forgiving of these murders".[18]

United States v. Lileikis

In late 1982, Lileikis was mentioned in a cable from Berlin as a potential war criminal and head of the Lithuanian Security Police, who had possible connections to Einsatzkommando 3, part of the Einsatzgruppen. The same week, another Lithuanian-American named him as a Nazi collaborator in an interview. This attracted the attention of Eli Rosenblum, who was working as an investigator for the OSI. After gathering information on Lileikis, Rosenblum went to his residence to question him. Lileikis admitted his leadership of the Lithuanian Security Police, but denied his involvement in the killings, stating that he had only done routine security work. Lileikis claimed that he heard rumours that the Germans killed Jews at Ponary but that it was done without Lithuanian participation.[23]

In late 1994, the OSI opened civil denaturalization proceedings against him, seeking to strip Lileikis of his United States citizenship under Section 340(a) of the Immigration and Naturalization Act,[24] which requires United States district attorneys to open civil proceedings against naturalized citizens suspected of lying on their immigration paperwork.[25] At the time, Lileikis was the oldest person to be subject to such an action. The CIA tried to stop the case from being filed, threatening not to allow the disclosure of some of the classified records in court.[26] Describing Lileikis as "one of the most important Nazi collaborators" to be investigated by the United States, OSI accused Lileikis of lying about his World War II activities on his immigration paperwork. Lileikis refused to comment on the allegations to the Associated Press and invoked the Fifth Amendment when questioned by prosecutors.[27][11] Lileikis refused to state even simple details on his life, such as his date and place of birth. Under federal law, the Fifth Amendment applies only to criminal proceedings; the prosecution argued that Lileikis should not be entitled to Fifth Amendment protection because he was not subject to criminal prosecution in the United States. The defense argued that Lileikis had a legitimate fear of prosecution in Lithuania, and should therefore not be compelled to testify.[28][29]

In 1995, Judge Richard Stearns of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts ruled that Lileikis was not entitled to Fifth Amendment protection because the government had a "legitimate need for a witness's testimony" in enforcing "the organic laws of the United States".[30][31] On 16 November, he granted the prosecution's motion to compel Lileikis' testimony; since he still refused to testify, the prosecution filed another motion on 18 December seeking that allegations which Lileikis refused to answer be admitted as if Lileikis had confessed to them. This motion was granted by the court on 9 January 1996.[32] The Holocaust historian Yitzhak Arad and several other experts submitted affidavits along with more than a thousand pages of archival documents relating to the Nazi occupation of Lithuania, the Holocaust in Lithuania, and Lileikis' activities.[33] On 24 May 1996, Stearns found him responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Jews.[1][33] The judge noted that Lileikis was "attempting to turn the classic Nuremberg defense on its head by arguing that 'I was only issuing orders.'" Lileikis was immediately denaturalized with the judge stating that he should never have been allowed into the United States.[19]

Genocide trial in Lithuania

Lileikis voluntarily left the United States on 18 June 1996, using a Lithuanian passport to fly to Vilnius. United States officials stated that he would be refused readmission to the country, and Polish authorities indicated that he could face trial in Poland for the murders of Polish Jews in Vilnius.[34] Lithuania initially indicated that he would not be prosecuted due to the lack of eyewitnesses.[35] In 1997, he told the Lithuanian newspaper Respublika that "All of us were collaborators—the whole nation, since it was acting according to Nazi laws" and acknowledged that he had made "mistakes".[21] Lileikis published a memoir in Lithuanian before his death, which is a useful source on his life if not "entirely accurate" on his World War II activities.[36] He claimed to be part of the anti-Nazi resistance.[21] Lithuania was slow to prosecute Lileikis. At the time, the country sought membership in NATO and the United States asserted that prosecution of Lileikis and other war criminals would be strong evidence of adherence to "western values," a prerequisite to joining the alliance. The message was relayed by the United States Vice President Al Gore during a meeting with the speaker of the Seimas in April 1997 and by thirty members of Congress in a November 1997 letter to the President of Lithuania.[37]

On 6 February 1998, Lileikis was charged with the crime of genocide by Lithuanian prosecutors.[1] It was the first Nazi war crimes prosecution in post-Soviet Eastern Europe.[38] He appeared in court in November 1998, but fainted just after few minutes and was taken away in an ambulance. Three special laws were passed in order to enable continuing prosecution of Lileikis and his former deputy Gimžauskas[1] (who had left the United States in 1995, facing denaturalization proceedings).[39] One of the changes allowed video evidence during genocide trials.[1] He was questioned over video on 23 June 2000 but after twenty minutes the proceedings were interrupted by an attending doctor and Lileikis was taken to a hospital.[40] The U.S. Department of Justice and Jewish organizations accused him of feigning illness.[21] The Simon Wiesenthal Center accused Lithuanian authorities of deliberately prolonging the trial in hopes that Lileikis would die of natural causes before he could be convicted.[21] The trial was well-publicized in Lithuania.[41] Lileikis died of a heart attack at Santara Clinics in Vilnius on 26 September 2000,[8] still insisting on his innocence and that he was the victim.[1][42] His funeral at the Vaiguva cemetery was attended by about a hundred people, including Mindaugas Murza, a radical nationalist.[2][43]

References

- "Aleksandras Lileikis". TRIAL International. 14 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- BNS (29 September 2000). "Nacionalistai A.Lileikio laidotuvėse kalbų nesakė" (in Lithuanian). Delfi.lt. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Stankeras 2008, p. 696.

- MacQueen 2004, p. 6.

- Balkeilis 2012, p. 142.

- Bubnys, Arūnas (1997). "Vokiečių ir lietuvių saugumo policija (1941–1944)". Genocidas Ir Rezistencija (in Lithuanian). 1. ISSN 1392-3463.

- Eschenazi, Gabriel (19 May 1998). "Lithuanian judge delays trial of alleged Nazi war criminal". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- BNS (27 September 2000). "Prokuratūra apgailestauja, kad nespėta nuteisti A.Lileikio" (in Lithuanian). Delfi.lt. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- McMahon, Colin (18 October 1998). "Trial Forces Lithuanians to Look Back on WW II". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- MacQueen 2004, pp. 7–8.

- Skorneck, Carolyn (21 September 1994). "Boston Retiree Accused as Holocaust Perpetrator". AP News. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Naftali 2005, pp. 340–341.

- Naftali 2005, p. 363.

- Lichtblau 2014, p. 217.

- Naftali 2005, p. 364.

- Naftali 2005, pp. 364–365.

- Naftali 2005, p. 374.

- Naftali 2005, p. 365.

- Lichtblau 2014, p. 225.

- Lichtblau 2014, p. 218.

- Reynolds, Maura (30 September 2000). "Nazi Collaborator Aleksandras Lileikis Dies at 93 in Lithuania". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Lichtblau 2014, p. 219.

- Lichtblau 2014, pp. 219–220.

- Mackey 1996, p. 17.

- Immigration and Naturalization Act, 340(a)

- Lichtblau 2014, p. 223.

- Lichtblau 2014, pp. 223–224.

- Rotsztain 1996, p. 1940.

- Mackey 1996, p. 18.

- Rotsztain 1996, p. 1958.

- Mackey 1996, p. 20.

- Mackey 1996, pp. 20–21.

- Mackey 1996, p. 21.

- "Accused Nazi leaves United States". UPI. 19 June 1996. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Feigin 2009, p. 462.

- MacQueen 2004, p. 5.

- Feigin 2009, pp. 462–463.

- Feigin 2009, p. 463.

- Feigin 2009, p. 482.

- BNS (24 June 2000). "Po teismo posėdžio pablogėjus sveikatai, greitosios medicinos pagalbos medikai penktadienį apie vidurdienį į Santariškių klinikas iš artimųjų buto Vilniuje išvežė karo nusikaltimais kaltinamą Aleksandrą Lileikį". Delfi.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Weiss-Wendt 2008, p. 477.

- Lichtblau 2014, p. 226.

- "Girdėta iš Vilniaus" (PDF). Dirva (in Lithuanian). 38 (LXXXV): 2. 10 October 2000.

Sources

- Balkeilis, Tomas (2012). "Turning Citizens into Soldiers: Baltic Paramilitary Movements after the Great War". In Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John (eds.). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe After the Great War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 126–144. ISBN 978-0-19-965491-8.

- Feigin, Judy (2009). Richard, Mark M. (ed.). The Office of Special Investigations: Striving for Accountability in the Aftermath of the Holocaust (PDF). Department of Justice. ISBN 978-1-63273-001-5.

- Lichtblau, Eric (2014). The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's Men. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-66919-9.

- Mackey, David S. (1996). "Fear of Foreign Prosecution and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination". United States Attorneys Bulletin. Executive Office for United States Attorneys. 44 (5): 17–21.

- MacQueen, Michael (2004). Lithuanian Collaboration in the "Final Solution": Motivations and Case Studies (PDF). Lithuania and the Jews: The Holocaust Chapter. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 1–15.

- Naftali, Timothy (2005). "The CIA and Eichmann's Associates". U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge University Press. pp. 337–374. ISBN 978-0-521-61794-9.

- Rotsztain, Diego A. (1996). "The Fifth Amendment Privilege Against Self-incrimination and Fear of Foreign Prosecution". Columbia Law Review. 96 (7): 1940–1972. doi:10.2307/1123297. JSTOR 1123297.

- Stankeras, Petras (2008). Lietuvių policija Antrajame pasauliniame kare (in Lithuanian). Mintis. ISBN 978-5-417-00958-7.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2008). "Why the Holocaust does not matter to Estonians". Journal of Baltic Studies. 39 (4): 475–497. doi:10.1080/01629770802461530. ISSN 0162-9778. JSTOR 43212850. S2CID 143954319.

Further reading

- Lileikis, Aleksandras (2000). Pažadinto laiko pėdsakais: atsiminimai, dokumentai [In the Footsteps of Times Past: Memories, Documents] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstiečių laikraštis. ISBN 978-9986-847-28-1.