Unknown Sailor

The Unknown Sailor was an anonymous seafarer murdered in September 1786 at Hindhead in Surrey, England. His murderers were hanged in chains on Gibbet Hill, Hindhead the following year.

Murder

The Unknown Sailor is first recorded as visiting the Red Lion Inn at Thursley as he was walking back from London to join his ship at Portsmouth on 24 September 1786. There he met three other seafarers, James Marshall, Michael Casey and Edward Lonegon. He generously paid for their drinks and food and was last seen leaving for Hindhead Hill with them. The three seafarers murdered him and stripped him of his clothes. The three then made their way down the London to Portsmouth road (now the A3) and were arrested a few hours later trying to sell the murdered sailor's clothes at the Sun Inn[1] in Rake (not the Flying Bull in Rake as some versions of the story have it). The Hampshire Chronicle, dated 2 October 1786, reads:

Sunday last a shocking murder was committed by three sailors, on one of their companions, a seaman also, between Godalming – They nearly severed his head from his body, stripped him quite naked, and threw him into a valley, where he was providentially discovered, soon after the perpetration of the horrid crime, by some countrymen corning over Hind Head, who immediately gave the alarm, when the desperadoes were instantly pursued, and overtaken at the house of Mr. Adams, the Sun, at Rake. They were properly secured, and are since lodged in gaol, to take their trials at the next assizes for the county of Surrey.

Six months later they were tried at Kingston assizes and two days after that, on Saturday 7 April 1787, they were hanged in chains on a triple gibbet close to the scene of the crime in Hindhead.[2]

Memorials

Front of Sailor's Stone

Front of Sailor's Stone Reverse of Sailor's Stone

Reverse of Sailor's Stone The granite Celtic Cross on Gibbet Hill

The granite Celtic Cross on Gibbet Hill

Gravestone

The unknown sailor was buried in Thursley churchyard and the gravestone was paid for by the residents of the village.(Moorey 2000: p. 1) It reads:

In memory of

A generous but unfortunate Sailor

Who was barbarously murder'd on Hindhead

On September 24th 1786

By three Villains

After he had liberally treated them

And promised them his farther assistance

On the road to Portsmouth.

The gravestone is a Grade-1 listed building and has recently (2010) been "cleaned and refreshed".[3]

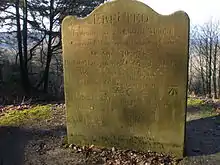

Sailor's Stone

The Sailor's Stone was erected by James Stillwell of nearby Cosford Mill soon after the murder. It was sited on the Old Coaching Road from London to Portsmouth close to the site of the murder. The inscription on the front of the stone reads:

ERECTED

In detestation of a barbarous Murder

Committed here on an unknown Sailor

On Sep, 24th 1786

By Edwd. Lonegon, Mich. Casey & Jas. Marshall

Who were all taken the same day

And hung in Chains near this place

Whoso sheddeth Man's Blood by Man shall his

Blood be shed. Gen Chap 9 Ver 6

[The following part of the inscription was clearly added at a later date:]

See the back of this stone

THIS STONE WAS ERECTED

A.D. 1786 BY JAMES STILLWELL ESQRE. OF COSFORD

AND WAS RENOVATED SEP 24TH 1889 BY

JAMES JOHN RUSSELL STILLWELL ESQRE OF KILLINGHURST

THE DESCENDANT AND REPRESENTATIVE OF THE STILLWELLS

OF COSFORD AND MOUSHILL

The inscription on the back of the stone reads:

THIS STONE

was Erected

by order and at

the cost of

James Stilwell Esqr.

of

Cosford

1786

Cursed be the Man who injureth

or removeth this Stone

When the London to Portsmouth road was realigned in 1826 the stone was removed and placed alongside the Punch Bowl bend. It was then removed back to its original location (and the curse on the back of the stone added). The stone was then returned down to the Punch Bowl road. Finally the stone was moved again in 1932 back to its original location when the main road was widened.[4]

The latitude and longitude of the Sailor’s Stone are 51°06′52.5″N 0°43′6.9″W.

Celtic Cross

In 1851 Sir William Erle paid for the erection of a granite Celtic Cross on Gibbet Hill on the site of the scaffold. He did this to dispel the fears and superstitions of local people and to raise their spirits.(Moorey. 2000: p. 1)

The cross has four Latin inscriptions around its base. They read:

POST TENEBRAS LUX

IN OBITU PAX

IN LUCE SPES

POST OBITUM SALUS

which translate to "Light after darkness. Peace in passing away. Hope in light. Salvation after death."[5]

The latitude and longitude of the Celtic Cross are 51° 06’ 56.1”N, 0° 42’ 58.2”W.

Gilbert White

Gilbert White of Selborne records, in his Naturalist's Journal 1768–1793, that on 23 December 1790 there was a terrible thunderstorm during which:

Two men were struck dead in a wind-mill near Rooks-hill on the Sussex downs: & on Hind-head one of the bodies on the gibbet was beaten down to the ground.[6][7]

Turner's Liber Studiorum

Between 1807 and 1809 the painter Turner created a collection of 71 Mezzotints under the title Liber Studiorum. These were published in 1811. One of these (number 25, engraved by Robert Dunkarton) was of Hindhead Hill with the gibbet clearly shown:

On his return to London from Spithead in the winter of 1807 Turner was stimulated by the grisly associations of the place to compose some fragmentary verses, and when he made his preliminary drawing for his Liber plate he carefully delineated the forms of the three bodies on the gallows in allusion to the events of 1787. He reworked the outline of the gibbet in drypoint... so that it resembles a serif letter 'T'. Turner enjoyed visual punning and he may have intended the form to represent a macabre allusion to his own initial.[8]

The verses include the lines "Hind head thou cloud capt hill" and "Hark the kreaking Irons. Hark the screaching owl" (Moorey 2000: p. 8)

In popular literature

Nicholas Nickleby

Charles Dickens mentions the murder of the Unknown Sailor in Chapter 22 of his novel Nicholas Nickleby[9] published in 1838–39:

They [Nicholas Nickleby and Smike] walked upon the rim of the Devil's Punch Bowl; and Smike listened with greedy interest as Nicholas read the inscription upon the stone which, reared upon that wild spot, tells of a murder committed there by night. The grass on which they stood, had once been dyed with gore; and the blood of the murdered man had run down, drop by drop, into the hollow which gives the place its name. 'The Devil's Bowl,' thought Nicholas, as he looked into the void, 'never held fitter liquor than that!'

The Broom-squire

In the early nineteenth century, the Devil's Punch Bowl became inhabited by several families who enclosed portions of the western slopes of the Bowl for themselves. Here they pastured their sheep, goats, and cattle and gleaned profits of a trade which they monopolised: making and selling brooms. Rods supplied by coppices of Spanish chestnut served for handles, the long and wiry heather twigs for brush. They became known as the Broom-squires and were a fiercely independent folk. The chief Broom-squire families were the Boxalls, the Snellings, and the Nashes.[10] In 1896, the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould published his novel The Broom-Squire which tells the fictitious tragic story of Mehetabel, supposedly the daughter of the Unknown Sailor, and of her ill-treatment at the hands of Bideabout, one of the Broom-squires.[11]

Punchbowl Midnight

The 1951 children's novel Punchbowl Midnight[12] by Monica Edwards features the story of the Unknown Sailor and the Sailor's Stone. One of the characters, Tamzin Grey, believes that she has been cursed because she scratched her initials on the stone with a penknife.

"It was for his money they did it, of course," Lindsey said. "And there's a curse, you know."

"What sort of curse?"

"Someone put a stone where the crime was committed and it says on it, 'Cursed be the man who injureth or moveth this stone.'" ...

"Lindsey, are you sure it says 'injureth' as well as 'moveth'?"

"Of course. Why?"

"Well, it's a pretty slender outlook for me, then. I found the stone two days ago and I scratched my initials on it with the marline spike of my knife. Funny thing, I didn't notice any curse at all."

"It's on the back of the stone," said Lindsey.

The Man from Morocco

In The Man from Morocco or Souls In Shadows or The Black (US title) (1926) by Edgar Wallace, part of the story is reused in a modern setting. Haslemere police find an unidentified sailor, bludgeoned to death on the Portsmouth Road, at the edge of the Devil's Punchbowl. He is buried in a nameless grave in Hindhead churchyard.

"Ten years ago," he said, speaking with more than his ordinary deliberation, "the Haslemere police picked up a dying sailor on the Portsmouth Road." "I'm talking about The Black," said Welling, "and why he's a burglar—get that in your mind, Jack—a dying sailor with his life hammered out of him, and not a line or a word to identify him; a dying sailor that sleeps in a little churchyard in Hindhead, without a name to the stone that is over him. Ain't that enough to turn any man burglar?"

Identity

In his book Who was the Sailor murdered at Hindhead 1786 (2000), Peter Moorey argues the case that the Unknown Sailor's identity was Edward Hardman, born in 1752 in Lambeth, London.

Further reading

References

- Photograph of Sun Inn on Geograph website

- Moorey, Peter (2000). Who was the Sailor Murdered at Hindhead 1786. Blackdown Press. ISBN 0-9533944-2-5.

- "Facelift for sailor murder memorial stone". Surrey Live. 14 May 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Moorey, Peter (2000). Who was the Sailor Murdered at Hindhead 1786. Blackdown Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-9533944-2-5.

- Translation from National Trust information board beside cross.

- Project Gutenberg edition of The Natural History of Selborne

- Gilbert White (23 December 1790). "The Natural History of Selborne". Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- Forrester, Gillian. 1996. Turner's Drawing Book, The Liber Studiorum Tate Publishing ISBN 978-1-85437-182-9

- Dickens, Charles. 1838-9. Nicholas Nickleby (Full text of Nicholas Nickleby at Project Gutenberg)

- Wright, Thomas. 1898 Hindhead or the English Switzerland Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co Ltd

- Baring-Gould, Sabine. 1896. The Broom-squire (Full text of The Broom-squire at Project Gutenberg)

- Edwards, Monica. 1951. Punchbowl Midnight Collins