Urbain Grandier

Urbain Grandier (1590 – 18 August 1634) was a French Catholic priest who was burned at the stake after being convicted of witchcraft, following the events of the so-called "Loudun possessions". Most modern commentators have concluded that Grandier was the victim of a politically motivated persecution led by the powerful Cardinal Richelieu.

Urbain Grandier | |

|---|---|

Grandier in 1627 | |

| Born | 1590 |

| Died | 18 August 1634 (aged 43–44) Loudun, Kingdom of France |

| Cause of death | Execution by burning |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Criminal charge | Witchcraft |

The circumstances of Father Grandier's trial and execution have attracted the attention of writers Alexandre Dumas père, Eyvind Johnson, Aldous Huxley and the playwright John Whiting, filmmaker Ken Russell, composers like Krzysztof Penderecki and Peter Maxwell Davies, as well as historian Jules Michelet and various scholars of European witchcraft.

Life

Grandier attended the Jesuit college of La Madeleine in Bordeaux. His uncle was a priest who held some influence with the Jesuits there. They held the right to appoint the parish priest for the Church of Saint-Pierre-du-Marche in Loudun, and in 1617 chose Grandier. They also had the right to name a canon to the collegiate Church of Sainte Croix, also in Loudun, and Grandier was appointed to that as well. Thus, as the eldest son, he was able to support his widowed mother and siblings. That he should receive both valuable positions over a local candidate caused some resentment.[1] Both benefices were in the Diocese of Poitiers.

Sometime around 1629 or 1630, Philippa Trincant, daughter of Louis Trincant, the king's prosecutor and a friend of Grandier, gave birth to a son. It was widely suspected that Grandier was the father.[1] He was also believed to have had intimate relations with a number of women.[2]

Allegations of sorcery

In 1632, a group of nuns from the local Ursuline convent accused him of having bewitched them, sending the demon Asmodai, among others, to commit evil and impudent acts with them. Aldous Huxley, in his non-fiction novel, The Devils of Loudun, argued that the accusations began after Grandier refused to become spiritual director of the convent, unaware that the Mother Superior, Jeanne des Anges, had become obsessed with him after having seen him from afar and heard of his sexual exploits. According to Huxley, Mother Jeanne, enraged by his rejection, instead invited Canon Jean Mignon, an enemy of Grandier, to become the director. Jeanne then accused Grandier of using black magic to seduce her. The other nuns gradually began to make similar accusations. However, Monsieur des Niau, Counsellor at la Flèche, said that Grandier applied for the position, but that it was instead awarded to Canon Jean Mignon,[2] a nephew of Monsieur Trincant.[1]

The Archbishop of Bordeaux intervened and ordered the nuns sequestrated, upon which the instances of possession seemed to have stopped.[3]

Richelieu

Grandier had gained the enmity of the powerful Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister of France. In its continuing efforts to consolidate and centralize power, the Crown had ordered the walls around Loudun to be demolished. The populace were of two minds concerning this, whether to keep the wall or rely on the central government for protection. Grandier supported those who wished to retain the walls.[4] In addition, not only had Grandier written a book attacking the discipline of clerical celibacy,[5] he had also penned a scathing satire on the cardinal.

Around the time of the nuns' accusations, M. Jean de Laubardemont, a relative of the Mother Superior of the convent of Loudun, was sent to demolish the town tower. He was prevented from doing so by the town militia, and upon returning to Paris reported on the state of affairs in Loudun including the recent disturbance at the Ursuline convent. In November 1633, Laubardemont was commissioned to investigate the matter. Grandier was arrested and confined to the prison at Angers. Laubardemont returned to Paris, where letters in support of Grandier from the Bailly of Loudun to the Procurator-General of the Parliament, stating that the possession was an "imposture" were intercepted.[2]

Trial

Laubardemont returned to Loudun with a Decree of the Council, dated 31 May 1634, confirming all his powers and prohibiting Parlement and all other judges from interfering in the matter, and forbidding all parties concerned from appealing, under penalty of a fine of five hundred livres. Grandier, who had been held at the prison of Angers was returned to Loudun. Both the examination of witnesses and the exorcisms of the Ursulines continued. After Grandier had been tortured, documents were introduced purportedly signed by him and several demons as evidence that he had made a diabolical pact. It is not clear whether Grandier wrote or signed the pacts under duress, or whether they were forged.

Grandier was found guilty and sentenced to death. The judges who condemned Grandier ordered that he be put to the "extraordinary question", a form of torture which was usually, but not immediately, fatal, and was therefore administered to only those victims who were to be executed soon afterwards. In addition, Grandier was subjected to a form of the Spanish boot, an iron vise filled with spikes, that was brought to red heat and then applied to the calves and ankles to shatter the bones. Despite torture, Grandier never confessed to witchcraft. He was then burned alive at the stake.

Many theories exist as to the cause of the Loudun "possessions". One of the most likely explanations is that the whole affair was orchestrated by Richelieu. Huxley in his book The Devils of Loudun (1952) and in the Ken Russell film version of the Huxley book (1971) alleged that the initial accusations against Grandier by the nuns of the convent of Loudun were part of a case of collective hysteria.

Augustin Calmet, among others, compared this case to the pretended possession of Martha Broissier (1578), which received a great deal of circulation at the time. This criticism was in part due to the fact that the circumstances revolving the incidents and the examinations of possession in question show more indications of pretended possessions than that of more dominantly legitimate cases, such as the possession of Mademoiselle Elizabeth de Ranfaing (1621).[6] In his Treatise, it is stated that the causes of the injustice committed at Loudun were a mixture of political ambition, the need for attention, and a basic desire to dispose of political opponents. The Loudun affair took place in the reign of Louis XIII; Cardinal Richelieu is accused of having caused this tragedy, in order to ruin Grandier, the Curé of Loudun, for having written a cutting satire against him.[7]

Diabolical pact

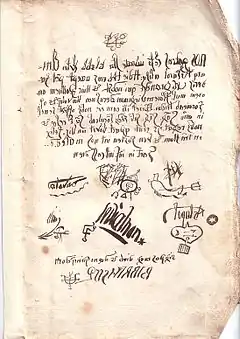

One of the documents introduced as evidence during Grandier's second trial is a diabolical pact written in Latin and apparently signed by Grandier. Another, which looks illegible, is written backwards, in Latin with scribal abbreviation, and has since been published and translated in a number of books on witchcraft. This document also carries many strange symbols, and was signed by several demons including Satan himself.[8] Deciphered and translated to English, it reads:

We, the influential Lucifer, the young Satan, Beelzebub, Leviathan, Elimi,

and Astaroth, together with others, have today accepted the covenant pact

of Urbain Grandier, who is ours. And him do we promise

the love of women, the flower of virgins, the respect of monarchs, honours, lusts and powers.

He will go whoring three days long; the carousal will be dear to him. He offers us once

in the year a seal of blood, under the feet, he will trample the holy things of the church and

he will ask us many questions; with this pact, he will live twenty years happy

on the earth of men, and will later join us to sin against God.

Bound in Hell, in the council of demons.

Lucifer Beelzebub Satan

Astaroth Leviathan Elimi

The seals placed the Devil, the master, and the demons, princes of the lord.

Baalberith, writer.

Artistic depictions

An 18th-century book written by historian Nicholas Aubin contains his findings on the Devils of Loudun. The book is titled, "The Cheats and Illusions of Romish Priests and Exorcists Discovered in the History of the Devils of Loudun."[9]

Grandier's trials were the subject of two treatments by Alexandre Dumas, père: an entry in volume four of his Crimes Célèbres (1840) and a novel, Urbain Grandier (1850).

The French historian Jules Michelet discussed Grandier in a chapter of La Sorcière (1862).

The Swedish author Eyvind Johnson based his 1949 novel Drömmar om rosor och eld on Grandier and the Loudun possessions.[10]

The same subject was revisited in the book-length essay The Devils of Loudun, by Aldous Huxley, published in 1952. Huxley's book was adapted for the stage in 1961 by John Whiting (commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company). The play was adapted for the movie screen by Ken Russell in 1971 (as The Devils). The novel was also adapted for the opera stage in 1969 by Krzysztof Penderecki (as Die Teufel von Loudun). It was also an inspiration for Matka Joanna od Aniołów (Mother Joan of the Angels) – a film by Jerzy Kawalerowicz after the story ("Matka od Aniołów|Mother Joan of the Angels") by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz.

Grandier is the subject of "Grandier's Funeral Pyre", a song by Elvenking off the album The Pagan Manifesto (2014).

Grandier is also the subject of the song "Devils" by the pagan rock band Inkubus Sukkubus from their 1993 album Wytches.

Florida death metal band Morbid Angel used Grandier's life as one of the main themes for their album Covenant.

The Loudun possessions and Grandier's trial are the subject of Les brasiers ne s'éteignent jamais ("The Braziers Never Go Out") by Michel Gaudo, an adventure module for the French horror RPG Malefices. Learning about the historical case helps the investigators solve the mystery.

Grandier is portrayed by Oliver Reed in the 1971 Ken Russell film The Devils.

References

- Rapley, Robert. A Case of Witchcraft: The Trial of Urbain Grandier, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 2001 ISBN 9780773523128

- Monsieur des Niau, La Veritable Histoire des Diables de Loudun, (Edmund Goldsmid, ed.) Edinburgh, 1887

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Gasparin, Agénor de. A Treatise on Turning Tables: The Supernatural in General, and Spirits, Vol. 2, Kiggins, 1857, p. 165

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Hunter, Mary Kay. "The Loudun Possessions: Witchcraft Trials", Legal History & Rare Books, American Association of Law Libraries Vol. 16 No. 3 Hallowe’en 2010

- Arrest de condemnation de mort contre maistre Urbain Grandier... Paris, Etienne Hebert, 1634

- Calmet, Augustin (30 December 2015). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 138–143. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- Calmet, Augustin (30 December 2015). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 515. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- "Father Urbain Grandier's Deal with the Devil, a Contract Signed by Satan".

- Aubin, b ca 1655; Des Niau (1703). "The cheats and illusions of Romish priests and exorcists. Discover'd in the history of the devils of Loudun: being an account of the pretended possession of the Ursuline nuns and of the condemnation and punishment of Urban Grandier a parson of the same town ." London, W. Turner [etc.] – via Internet Archive.

- Örjan Lindberger (1990) Människan i tiden. Eyvind Johnsons liv och författarskap 1938-1976, Bonniers ISBN 91-0-047904-7

Sources

- Huxley, Aldous (1953). The Devils of Loudun.

- Robbins, Rossell Hope (1959). The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. (see article on Urbain Grandier)