Wide stingaree

The wide stingaree (Urolophus expansus) is a little-known species of stingray in the family Urolophidae, found off southwestern Australia. It typically occurs over sand in water 200–300 m (660–980 ft) deep around the edge of the continental shelf. This species has a broad diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc, a slightly pointed snout, and a tail with a leaf-like caudal fin, skin folds along either side, and no dorsal fins. Between its nostrils is a skirt-shaped curtain of skin. It is grayish green above, with faint bluish lines beside and behind the eyes. The maximum length on record is 52 cm (20 in).

| Wide stingaree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | U. expansus |

| Binomial name | |

| Urolophus expansus McCulloch, 1916 | |

The diet of the wide stingaree consists mainly of isopods and polychaete worms. It is aplacental viviparous, with the females supplying their unborn young with histotroph ("uterine milk"). This species is regularly caught incidentally by commercial trawl fisheries operating in the Great Australian Bight. Although it is unlikely to survive being captured and also tends to abort any gestating young during the process, large portions of the wide stingaree's range see little to no fishing activity and overall the species is not threatened. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed it under Least Concern.

Taxonomy

The first known specimens of the wide stingaree were collected from the Great Australian Bight by the research vessel FIS Endeavour, and described by Australian ichthyologist Allan Riverstone McCulloch in a 1916 volume of the scientific journal Biological Results Endeavour. The specific epithet expansus means "spread out" or "expanded" in Latin.[2] Another common name for this species is broadbacked stingaree.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The wide stingaree is endemic to southwestern Australia, occurring from Perth, Western Australia to Port Lincoln, South Australia.[4] One of the deeper-living representatives of its family, this benthic species inhabits the outer continental shelf and upper continental slope at a depth of 130–420 m (430–1,380 ft). It is most commonly found between 200 and 300 m (660 and 980 ft) down, over sandy areas. There is evidence for some degree of segregation by age and sex.[1]

Description

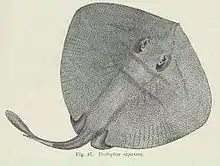

The wide stingaree has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc much wider than long, with broadly rounded outer corners and trailing margins. The anterior margins are gently sinuous and converge at an obtuse angle on the fleshy, slightly protruding snout. The eyes are large and immediately followed by comma-shaped spiracles with rounded posterior margins. There is a skirt-shaped curtain of skin with a shallowly fringed posterior margin between the nostrils. The mouth is of medium size and contains 6–9 papillae (nipple-like structures) on the floor; a narrow patch of papillae is also found on the lower jaw. The teeth are small with roughly oval bases. The five pairs of gill slits are short. The pelvic fins are small, with rounded edges.[4][5]

The tail measures 71–93% as long as the disc and has a highly flattened base and well-developed lateral skin folds; there is no dorsal fin, while the terminal caudal fin is lance-like and elongated. A serrated stinging spine is placed atop the tail about halfway along its length. The skin is completely smooth. This species is dusky green above, with two faint, bluish transverse lines behind the eyes and a pair of similar lines running obliquely outwards from the eyes. The underside is white to beige, darkening towards the disc lateral margins, with dark blotches on the tail. Juveniles have a dark caudal fin. The largest known specimen measures 52 cm (20 in) long.[4]

Biology and ecology

The wide stingaree is a poorly known species that preys mainly on isopods and polychaete worms. Like other stingrays, it is aplacental viviparous, with the developing embryos sustained by histotroph ("uterine milk"). The litter size is probably small as in related species. Males mature sexually at a disc width of 30–36 cm (12–14 in) and seven years of age, and have a maximum lifespan of 11 years. Females mature at a disc width of about 40 cm (16 in).[1][4] A known parasite of this species is a tapeworm of the genus Acanthobothrium.[6]

Human interactions

Edible though not marketed,[4] the wide stingaree is caught incidentally on a regular basis in otter trawls utilized by the Great Australian Bight Trawl Sector of the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (SESSF), and to a much lesser extent by the small-scale Western Deepwater Trawl Fishery (WDWTF) in the westernmost portion of its range. Captured individuals are unlikely to survive as they are brought up from such great depths, and furthermore stingarees have a tendency to abort their young when captured. However, the SESSF only operates over part of the Great Australian Bight, and so the overall level of fishing pressure across the wide stingaree's range is low. Therefore, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as of Least Concern.[1]

References

- Kyne, P.M.; Treloar, M.A. (2019). "Urolophus expansus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T60092A68649334. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T60092A68649334.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- McCulloch, A.R. (31 October 1916). "Report on some fishes obtained by the F.I.S. "Endeavour" on the coasts of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South and South-Western Australia". Biological Results Endeavour. Part IV. 4 (4): 169–199.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2010). "Urolophus expansus" in FishBase. September 2010 version.

- Last, P.R. & J.D. Stevens (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 414–415. ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- Last, P.R. & L.J.V. Compagno (1999). "Myliobatiformes: Urolophidae". In Carpenter, K.E. & V.H. Niem (eds.). FAO identification guide for fishery purposes: The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 1469–1476. ISBN 92-5-104302-7.

- Campbell, R.R. & I. Beveridge (2002). "The genus Acanthobothrium (Cestoda : Tetraphyllidea : Onchobothriidae) parasitic in Australian elasmobranch fishes". Invertebrate Systematics. 16 (2): 237–344. doi:10.1071/IT01004.