All My Good Countrymen

All My Good Countrymen, also translated as All My Compatriots, (Czech: Všichni dobří rodáci), is a 1968 Czechoslovak film directed by Vojtěch Jasný. Considered the "most Czech" of his contemporary filmmakers, Jasný's style was primarily lyricist.[1] It took nearly 10 years to complete the script and is his most renowned work. The movie was based on real people from Jasný's hometown Kelč. The film was banned[2] and the director went into exile rather than recant. It was entered into the 1969 Cannes Film Festival where Jasný won the award for Best Director.[3]

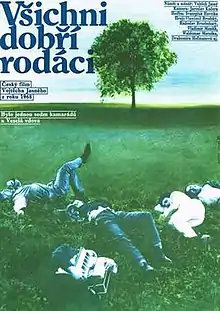

| All My Good Countrymen | |

|---|---|

Poster for the film | |

| Directed by | Vojtěch Jasný |

| Written by | Vojtěch Jasný |

| Produced by | Jaroslav Jílovec |

| Starring | Vlastimil Brodský |

| Cinematography | Jaroslav Kučera |

| Edited by | Miroslav Hájek |

| Music by | Svatopluk Havelka |

| Distributed by | Ústřední půjčovna filmů |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | Czechoslovakia |

| Language | Czech |

Cast

- Radoslav Brzobohatý as Peasant František

- Věra Galatíková as František's wife

- Vlastimil Brodský as Organist Očenáš

- Vladimír Menšík as Jořka Pyřk

- Waldemar Matuška as Peasant Zášinek

- Drahomíra Hofmanová as Widow Machačová

- Pavel Pavlovský as Postman Bertin

- Václav Babka as tailor Franta Lampa

- Josef Hlinomaz as Painter Frajz

- Karel Augusta as Bricklayer Joza Trňa

- Ilja Prachař as Photographer Josef Plecmera

- Václav Lohniský as Zejvala

- Jiří Tomek

- Helena Růžičková as Božka

- Oldřich Velen as Policeman

Plot

The film begins in 1945 and traces the seasonal or annual changes that a small Moravian village undergoes until the Epilogue, which is sometime after 1958.

The first part of the film set in 1945 establishes the innocence and camaraderie of a village amidst the backdrop of a post-War landscape. Children play with guns and a land mine is discovered while ploughing the fields. A group of villagers detonate it and end the night dancing and drinking in the local pub. They leave at dawn as the sun rises on a beautiful, idyllic landscape and stop to sleep beneath a tree after taking in the view.

In 1948, it is just months after the Communists have taken power in February. Loud speakers blare propaganda and announce rations while the farmer František works. We discover that four of the main villagers have converted, namely, the organist Očenáš, the photographer Plecmera, the postman Bertin, and Zejvala. The townspeople disdain them. A landowner must vacate his land so it can become a collective; his wife tearfully removes pictures of Jesus and the Virgin Mary from the walls as the landowner criticizes: "I hope you look after this place, your own looks like a pigsty." To which the communists respond ominously: "Don't worry! We will show you what we can do!" The communists greedily inspect their winnings (animals, house, a stockpile of wood) and begin to loot for themselves. Meanwhile, a tailor sets up shop with his wife and the help of friends, who warn him that the communists will put an end to his good fortunes. Indeed, a group of communists come and demand he turn over the property on which he has just spent his life's savings and lead a tailoring collective instead.

In 1949 the postman, Bertin, is shot after we see him and his wife-to-be, Machačová, being fitted for wedding clothes. A funeral is held after which police arrest those they deem responsible. František the noble farmer leads a mass of townspeople to demand the police turn over some of the wrongly accused perpetrators, namely the priest. The organist Očenáš, facing death threats, leaves at his wife's persistence. The photographer's wife, aspiring for status and a new house, implores her husband to fill the position left behind by Očenáš.

In 1951, Zášinek comes home drunk from a night at the bar. He hallucinates the ghost of his ex-wife, a Jew. He had divorced her because he feared the Germans and she had died in a concentration camp. Her ghost tells him that she has forgiven him. Nevertheless, his guilt drives him mad. He sees her again at an afternoon soiree and dances with her briefly. Meanwhile, Machačová, "the merry widow," shows up to the same soiree with the town thief, Jořka. He has been summoned to prison a few days prior and we understand that he is to report that afternoon. After dancing, he bids her farewell and walks off, presumably toward the prison. He stops and pours acid on his left foot, which starts to hiss and boil. He returns a clock he had stolen, repaired, to its rightful owner, then collapses from his wound and dies as white goose down covers him like snow.

In Autumn 1951, Zášinek is still upset about his guilt. He visits the church to confess. He is shown later at a pub amidst friends and the merry widow. They dine and soon begin to dance, all while being painted. The painting shifts from formless shapes to lackluster diners to a frenzied dance, with Zášinek soon depicted as a devil with a skull. He returns home the next morning drunk and is impaled by a loose bull and dies.

In 1952, František's weary father comments on how his strength is failing with age. At a townhall meeting, the communists announce they will take more loans; the panel clap for each other. The audience does not clap; František speaks against the decision and leads away the villagers. The communists seek to destroy him, for "as long as he is around, nothing will get done." He is arrested; police attempt to get others to sign statements alleging his guilt but with no immediate success—the villagers hold out until they are threatened.

In 1954, A communist who had stolen from the original confiscated house returns. He is called a disgrace and dismissed. František has escaped from prison but he is sick and near death.

In 1955, František's health rebounds. He no longer has anything but buys a horse and sets to work again. The narrator asks, "which can bear more, a man or a horse? A man, because he has to."

In 1957, Realizing that the village rallies around the noble František, the communists ask him to persuade the others to declare their harvests. František refuses. After being forced, all villagers sign except Frantisek.

In 1958, František is taken to the home originally seized from the landowner. It has been poorly taken care of; he agrees to take it on and become the collective's leader. On his way to assume the role, he and his daughter's carriage are stopped by a carnival procession of villagers masked with the heads of animals and monsters. They are gentle to him and he laughs as he continues. The mob moves next to an oncoming car. It is the photographer and his wife. They stop it, pull them out and dance. The photographer's merriment is cut short as he clutches his chest and falls to the snow with a heart attack. Later the townspeople amassed at the pub remove their animal masks and remark: "soon all the people will be gone and all that will be left are the animals."

In the Epilogue, Očenáš returns to the village. He runs into the now-blind and divorced photographer who has tumbled from power. Očenáš asks about František, who he discovers has recently died. The photographer remarks: "the best people go and the blackguards stay." Očenáš visits František's family and speaks with his daughters, who tell him the farmer's last words were to "listen to the workers in the fields"-- "things will be better when they begin to sing again." Očenáš departs on his bike and looks back forlornly on the countryside as he laments: "We have made our beds and now we have to lie in them. But have we made them ourselves? What have we done, rather, what have we undone, all my fellow countrymen?"

Accolades

| Date of ceremony | Award | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Cannes Film Festival | Best Director | Vojtěch Jasný | Won | [4] |

| Technical Grand Prize - Special Mention | Vojtěch Jasný | Won | |||

| Palme d'Or | Vojtěch Jasný | Nominated | |||

| Plzeň Film Festival | Golden Kingfisher (Best Film) | Vojtěch Jasný | Won |

Sequel

In 1977 an unofficial spiritual sequel The Moravian Land was released. It was directed by Antonín Kachlík. The film was meant to be a counterbalance to All My Compatriots. Many actors from All My Compatriots also starred in the Moravian Land. It presented collectivization as a positive thing.[5]

Vojtěch Jasný directed Return to Paradise Lost in 1999. It is a loose continuation to All My Compatriots. It stars Vladimír Pucholt as a Czech émigrée who returns home after fall of Communist regime. He comes from the village showed in All My Compatriots. Some characters returned in this sequel.[6]

Notes

- Liehm, Antonin. Closely Watched Films: Vojtěch Jasný. 1974.

- Robert Buchar (29 October 2003). Czech New Wave Filmmakers in Interviews. McFarland. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-7864-1720-9.

- "Festival de Cannes: All My Compatriots". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- "Vsichni dobrí rodáci". IMDB. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Jaroš, Jan. "Zákruty filmové kolektivizace". Kultura21.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Ceska Televize. "Návrat ztraceného ráje". Česká televize (in Czech). Retrieved 24 August 2017.

References

- Liehm, Jan Anonín; Liehm, Mira (1977). The Most Important Art. Soviet and Eastern European Film After 1945. Berkeley-Los Angeles-London. p. 302.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hames, Peter (1985). The Czechoslovak New Wave. Berkeley. pp. 60–61.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Český hraný film IV. (1961-1970) (in Czech). Prague: Národní filmový archiv. 2004. p. 416. ISBN 80-7004-115-3.