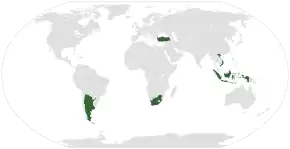

VISTA (economics)

VISTA is an acronym for Vietnam, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey, Argentina,[1] used in economics in grouping and discussing emerging markets.[2] The concept was first proposed in 2006 by BRICs Economic Research Institute of Japan,[3][4] but has not been significantly popularised in the academic and business world. This has led to economic experts proposing different definitions and implications of VISTA. While some see the economic potential of these emerging economies as individually promising, others challenge that the concept of economic acronyms is limiting as the countries' social and development factors are usually not taken into account.[5] For investors, VISTA has been considered as an opportunity to enter into a newly–emerging market,[4] particularly following the post-BRICS era.

Definition

VISTA does not have a standardised definition or economic thesis due to the acronym’s limited usage. Subsequently, this has led to economic and business experts holding different propositions on the definition and implications of VISTA. While some see the economic potential of these emerging economies, others challenge the concept of economic acronyms, as the countries' social and development factors are usually not taken into account.[5]

For investors, VISTA has been considered as an opportunity to enter a newly emerging market, particularly following the post-BRICS era.[4] However, these developing economies are also characterised by higher levels of volatility and are generally more vulnerable to economic instabilities. This has led to some experts describing VISTA as “just…a second-tier group”,[4] and not an ultimate substitute to the BRICS.

Economic implications

All members in VISTA are included in the 25 largest emerging economics, according to World Economic Outlook[6] with projected increase in levels of gross domestic product (GDP), investments and trade. Much of the growth in VISTA economies are accompanied by development in technology, natural resources, and finance sectors. Some economies in VISTA, which have attained notable economic presence, are already part of other economic groupings and acronyms. They include Vietnam, Indonesia and Turkey in CIVETS, Indonesia in MINT and South Africa in BRICS.

In the financial market, VISTA has been regarded as a new investing strategy, and an alternative way for investors to enter the emerging market. There has been an increasing trend to invest in other emerging economies, particularly after the lower returns in BRICS countries.[4] Some VISTA countries – South Africa, Turkey and Argentina – have already been in emerging market investment portfolios for some time.

Members

Vietnam

.jpg.webp)

After gaining independence in 1954, Vietnam’s economy was largely defined by subsistence agriculture, with undeveloped infrastructure and low levels of education and entrepreneurship.[7] From 1986, the Vietnamese government adopted the economic reform Doi Moi, designed to transition the economy into a market based one.[7]

Since then, the economy has notably adopted the movement of globalisation by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and stimulating exports.[8] Its proximity to major Asian cities and particular demographic features (i.e., hardworking workforce, which is favoured by investors), have been key contributors to Vietnam’s integration into the global economy.[8] In 2010, it beat other Asian economies in levels of FDI stock/GDP and trade/GDP, which are important factors of economic openness.[8]

In 2021 Vietnam’s industry, construction and services sectors grew by 6.4%, particularly led by boosted external demand for manufactured products.[9] Vietnam is a current member of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a free trade area with GDP totalling £9 trillion and comprising 11 countries.[10] Vietnam and the UK, a prospective member for the CPTPP, strengthened its economic partnership in 2022, with the European country committed to “[share its] expertise in the renewable energy sector” with the Southeast Asian economy.[10]

Indonesia

Indonesia’s economic growth has been driven by investments and strong public consumption. Consumer demand was a particular contributor to its economic growth, making it a resilient economy, even in the face of the Financial crisis of crisis of 2007–2008.[11]

During the GFC, the Indonesian banking sector was protected by comprehensive regulations and banking practices, with sound level of profitability.[12] Both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund determined the country’s financial system was “generally healthy”.[12] With more prospects for FDI, Indonesia ranked among the top five as a FDI destination for investors in 2012–2014, according to UNTCD’s World Investment Prospects Survey.[13] During 2004–10, its manufacturing sectors receive the most FDI, with a proportion of 38.29%, followed by mining and quarrying. Such large shares in FDI indicate profitability is high in these sectors in Indonesia.[11] Such inflows of FDI are seen to be essential for the country's economic expansion.[12]

Indonesia is a member of the G-20 major economies, and the leader of Indonesia, Joko Widodo, is the current President of the intergovernmental group. An Australian economist in 2016 projected Indonesia would be the fourth largest in the world in terms of GDP based on per capita spending in 2050.[14] As the fourth largest economy in East Asia[15] and an export-led mercantilist,[16] Indonesia is expected to play a greater role in the global economy.

South Africa

South Africa has emerged to be one of the most diversified developing economies of sub-Saharan Africa, as a middle-income country.[17] The addition of South Africa to BRICS in 2010 was seen as an opportunity for African nations to be included in global economic stage, reinforcing the country as a significant developing economy.

Financial and technology sector are proving to be integral developers to the South African economy. Its financial market has shown strong performance, with high levels of competition and increased modernisation;[18] the South African rand, is the most actively traded currency in the emerging market.[11] Growth in the technological sector is also evident, particularly as competition and technological inflows have risen in the 2010s.

The South African government has implemented multiple programs to boost its economy in recent years. The Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (AsgiSA) was introduced in 2006. From 2004 to 2007, during the AsgiSA period, economic growth averaged over 5%.[19] Increased government intervention and policies, and subsequently more stable macroeconomic trends, will support the African economy in the future.

Turkey

As a demand-led economy[16] with the 20th largest nominal GDP in the world and 11th largest GDP-PPP in the world, Turkey has experienced steady growth in its economy. Its development has been complemented by changes in its GNP composition, with the provision of service sectors increasing.[20]

Ever since Turkey has embraced trade liberalisation with the EU in 1995, the elimination of trade barriers has allowed foreign trade volumes to increase in the country.[20] Continuing its openness to trade will provide Turkey the opportunity to further its growth.

The country is one of the 38 founding members of OECD (1961), an international group which prioritises social and economic progress.[21] Turkey is also a member of the G-20 economic group, an intergovernmental forum which seeks to solve global economic, political and social problems. According to the OECD, Turkey is projected to have significant rise in GDP (PPP), to be ranked as the 7th largest economy by 2040.[22] The economy was also marked to be one of the fastest growing economies as an OECD member, during 2015–2025.[23]

Argentina

.jpg.webp)

Despite several economic crises in the 1900s, Argentina stands as the second largest economy in South America and part of the G20 economic group. As a key, global producer in agriculture, the sector accounted for almost 6% of Argentina’s GDP in 2020.[24] Further, due to its abundance in natural resources, the industry is making increasing contributions to the economy, representing 3.2% of its GDP in 2016.[25]

After the Executive Board discussion in 2022, the Managing Director and Chair of IMF stated that “an economic and employment recovery [was] underway”, suggesting a positive outlook on Argentina’s economic prospects, as its government set “realistic objectives… [and] credible policies” to stabilise its macroeconomy.[26]

In 2011, Argentina saw close economic partnership and cooperation with the economic giant China, in several industries. This resulted in the volume of bilateral trade between the two economies growing to $17 billion.[27] 30 Chinese companies were recorded to have been operating in Argentina for business in “television production, mineral exploration, energy, finance… shipping and fishery” in 2013.[27]

The economy is a significant contributor particularly in the global provision of agricultural products. It is the largest exporter of soy products in the world, accounting for nearly 6% of the Argentina’s GDP.[28] Government attention to promote consumption due to the pandemic led to a growth in expenditure of non-durable goods in 2021.[28] The services sector is the biggest contributor to the country’s GDP, accounting for nearly 55% and employing 78.1% of Argentina’s workforce.[28]

Argentina is a member of the G-20 major economies, whilst identified as an upper-middle income country by the Word Bank and an emerging market by the FTSE Global Equity Index (2018).

Challenges

Despite positive economic projections for the members of VISTA, many are also facing social and political challenges which could hinder their growth. A shared challenge among these countries has been inappropriate or the lack of government responses. Argentina, for example, has historically experienced economic turmoil, with its policies “[defying] basic principles of good economic management”.[11]

There is also in the growing levels of debt among emerging economies. Since 2010, the debt-to GDP ratios have seen a rise of 60 percentage points to 165% in emerging economies.[29] This is especially with the members of VISTA such as Argentina (46%), Indonesia (39%) and Turkey (34%).[29]

South Africa’s setbacks have largely been identified by its level of poverty and unemployment. Although the country has taken measures to reduce poverty since 1994, around 55.5% of the South African population are still reported to live in poverty.[30] The nation’s Gini coefficient, at 63, is an indication of its economic inequality.[30]

Although Indonesia’s economy has proven to be resilient, its current trajectory of growth may not be sufficient for the country to be considered a “true, global economic power by 2030”.[31] Indonesia has fewer global firms compared to its Asian counterparts like Malaysia or Thailand, and its overseas direct investment holdings are half of Malaysia.[31] In 2010, the IMF and the World Bank found two primary issues that required the intervention of the Indonesian government – “protection and support of financial regulators, and weak creditor rights”.[12]

A 2019 McKinsey study also concluded that developing countries are in need of more than $2 trillion invested in infrastructure annually to keep up with the level of projected growth of gross domestic product for the next 15 years; biggest gaps in infrastructure spending are seen in Indonesia and South Africa.[32]

COVID-19 has also brought up or exacerbated economic challenges for emerging countries. As many emerging markets were already in a weaker economic position than the developed, they have been subject to significant decrease in portfolio investment inflows due to the pandemic.[29]

Criticism

A limitation of economic acronyms which group ‘comparable’ emerging economies together is that social and political factors, or levels of human development are not considered. A Quartz article challenged validity of relying on the economic profile of countries solely, to make projections about economic growth and to evaluate the successes as an investing strategy.[33] Instead, the article suggested that investors needed to study more "fundamental indicators related to fiscal health, political stability, infrastructure spending, and productivity"[33] to effectively see the countries' financial potential.

This critical view is also supported by research which suggests the correlation between access to health care and economic growth in VISTA countries. The study found evidence that Vietnam, Indonesia and South Africa have a significant, positive relationship between health and economic growth.[17]

Country profile

| Country | Population (2021)[34][35] |

Nom. GDP $USD (2022 est.)[36] |

PPP GDP $USD (2022 est.)[36] |

Nom. GDP per capita $USD (2022 est.)[36] |

PPP GDP per capita $USD (2022 est.)[36] |

real GDP growth (2021)[36] |

FDI % of GDP (2021)[37] |

HDI (2021)[38] |

Unemployment (2022 est.)[36] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97,468,029 | 413.808 | 1,299.690 | 4,162 | 13,074 | 5.8% | 0.703 | 2.4% | ||

| 273,753,191 | 1,289.429 | 4,023.501 | 4,691 | 14,638 | 1.8% | 0.705 | 5.5% | ||

| 59,392,255 | 411.480 | 949.846 | 6,738 | 15,555 | 1% | 0.713 | 34.6% | ||

| 84,775,404 | 853.487 | 3,320.994 | 9,961 | 38,759 | 1.1% | 0.838 | 10.7% | ||

| 45,276,780 | 630.698 | 1,207.228 | 13,621 | 26,073 | 1% | 0.842 | 6.9% |

Current leaders

See also

References

- Mori, Takeshi. "Promising Post-BRIC Emerging Markets" (PDF). NRI Papers. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "VISTA". The Free Dictionary.

- "VISTA - Worth a Look" (PDF). Henyep International Wealth Management.

- "EMERGING FX VIEW-Investors may trade off BRIC for VISTA". Thomson Reuters. 13 July 2007.

- Khanna, Parag (23 June 2013). "BRICS, VISTA, BROOMS—Just because it's an acronym doesn't mean it's an investment opportunity". Quartz. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022". IMF. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- Anh, Nguyen Thi Tue; Duc, Luu Minh; Chieu, Trinh Duc. "The Evolution of Vietnamese industry" (PDF) – via Brookings Institution.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Khuong, Vu Minh (2015). "Can Vietnam Achieve More Robust Economic Growth? Insights from a Comparative Analysis of Economic Reforms in Vietnam and China". Southeast Asian Economies. 32 (1): 52. doi:10.1355/ae32-1d. ISSN 2339-5095. S2CID 155085008.

- "Vietnam's economic growth driven by good recovery of sectors: WB". moit.gov.vn. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- "UK and Vietnam hold talks as trade increases by almost 11%". Mirage News. 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- Looney, Robert E., ed. (2018-10-04). Handbook of Emerging Economies. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203108765. ISBN 978-0-203-10876-5.

- Wie, Thee Kian (2010-09-25). "Indonesia's economy continues to surprise". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- "Global investment trends and prospects", World Investment Report 2021, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) World Investment Report (WIR), United Nations, pp. 1–35, 2021-08-02, doi:10.18356/9789210054638c006, ISBN 978-92-1-005463-8, retrieved 2022-05-08

- "Indonesia the Fourth Largest in GDP in 2050: Analysts - ANTARA News Jawa Timur - ANTARA News Jawa Timur - Berita Terkini Jawa Timur". 2016-10-24. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- Khobai, Hlalefang (2021-08-20). "Renewable Energy Consumption, Poverty Alleviation and Economic Growth Nexus in South Africa: Ardl Bounds Test Approach". International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy. 11 (5): 450–459. doi:10.32479/ijeep.7215. ISSN 2146-4553. S2CID 237349981.

- Karwowski, Ewa; Stockhammer, Engelbert (2017-01-02). "Financialisation in emerging economies: a systematic overview and comparison with Anglo-Saxon economies". Economic and Political Studies. 5 (1): 60–86. doi:10.1080/20954816.2016.1274520. hdl:2299/19936. ISSN 2095-4816. S2CID 157388799.

- Khobai, Hlalefang; Kolisi, Nwabisa; Mihlali Mbeki, Zizipho. "Health and economic growth in Vista countries: An ARDL bounds test approach" (PDF) – via Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "South Africa in the BRICS: Evolving International Engagement and Development". Harvard International Review. 2019-08-23. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- The Presidency Republic of South Africa. (2008). Annual Report 2008 Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/asgisa2008.pdf

- Yucel, Fatih (2009-01-01). "Causal Relationships between Financial Development, Trade Openness and Economic Growth: The Case of Turkey". Journal of Social Sciences. 5 (1): 33–42. doi:10.3844/jssp.2009.33.42. ISSN 1549-3652.

- OECD. "About the OECD". OECD Watch. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- "Domestic product - GDP long-term forecast - OECD Data". theOECD. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Reasons to Invest in Türkiye - Invest in Türkiye". www.invest.gov.tr. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- Thomas, G.P. (April 6, 2021). "Argentina: Mining, Minerals and Fuel Resources". AZO Mining.

- "IMF Executive Board Approves 30-month US$44 billion Extended Arrangement for Argentina and Concludes 2022 Article IV Consultation". IMF. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "China-Argentina ties booming CCTV News - CNTV English". 2014-01-11. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- "Economic and political outline Argentina - Santandertrade.com". santandertrade.com. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- OECD. "Business Insights on Emerging Markets 2021" (PDF) – via OECD Development Centre.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - The World Bank. "Poverty & Equity Brief South Africa" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Rajah, Roland (2018). "Indonesia's economy: Between growth and stability". Lowy Institute for International Policy.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - McKinsey & Company. "Unlocking private-sector financing in emerging-markets infrastructure".

- Khanna, Parag (23 June 2013). "BRICS, VISTA, BROOMS—Just because it's an acronym doesn't mean it's an investment opportunity". Quartz. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. 3 October 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- "World Development Indicators | DataBank". databank.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- Human Development Report 2021-22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World (PDF). 8 September 2022. pp. 272–276. ISBN 978-9-211-26451-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

External links

- VISTA overtaking BRICs for trust investments, 14 May 2007, J-Cast Business News, retrieved 2008-04-22

- EMERGING FX VIEW-Investors may trade off BRIC for VISTA, 13 July 2007, retrieved 2008-04-22

- BRICs and VISTA – The hidden potential of emerging nations, NTT Communications Japan

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)