Vacuum activity

Vacuum activities (or vacuum behaviours) are innate fixed action patterns (FAPs) of animal behaviour that are performed in the absence of a sign stimulus (releaser) that normally elicit them.[1] This type of abnormal behaviour shows that a key stimulus is not always needed to produce an activity.[2] Vacuum activities often take place when an animal is placed in captivity and is subjected to a lack of stimuli that would normally cause a FAP.[3]

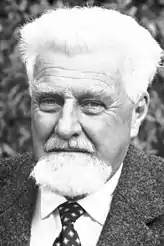

History

The term was first established by the ethologist Konrad Lorenz in the 1930s after observations of a hand-raised starling.[4] In 1937 Lorenz wrote: "With head and eyes the bird made a motion as though following a flying insect with its gaze; its posture tautened; it took off, snapped, returned to its perch, and with its bill performed the sideways lashing, tossing motions with which many insectivorous birds slay their prey against whatever they happen to be sitting upon. Then the starling swallowed several times, whereupon its closely laid plumage loosened up somewhat, and there often ensued a quivering reflex, exactly as it does after real satiation."[5]

Lorenz's hydraulic model of motivation

Animals that were raised without releasing instinctual behaviours, due to being in captivity or being taken as a pet, will produce these vacuum behaviours in seemingly random moments due to a build-up of energy reserves. This theory is based on Lorenz's Hydraulic Model of Motivation, which attempts to explain the mechanism of FAPs by equating energy input to water adding up in a container, leading to a valve which, under normal circumstances, is opened upon addition of a releaser or sign stimulus, to produce a FAP. When a sign stimulus or releaser is not present, this leads to an energy (water) build-up, forcing the valve open and producing the FAP in the absence of a stimulus.[6][2]

Evolution and genetics

Over time as animals have evolved, natural selection has favoured some behaviours over others because they have ensured the survival and reproduction of the animal.[7] These potentially long-lasting, innate behaviours have a genetic origin that propagates through evolutionary time, becoming slightly altered due to environmental changes and mutations.[7] The study of Epigenetics explains how certain mutations (e.g., histone modification and DNA methylation) affect how genes are expressed without altering the genetic code, suggesting learning from the environment can change gene expression, and thus neural pathways, to modify the animals behaviour within its lifetime.[7] These FAPs, or instinctual, stereotyped behaviours lead to the production of vacuum activities when the environment is lacking the necessary stimuli, revealing a deeply entwined relationship between an external stimulus in the environment, genes, and learning.[7] This is illustrated in the act of primates shaking branches in their natural environment to cause a distraction from predators and the inclination for captive primates in zoos to shake roof beams even though they cannot know if a predator is outside.[8] The animals physiology is attempting to produce an instinctual behaviour that is common for that particular species but the necessary external stimulus is not present.

Examples

Birds

Lorenz observed that a starling bird snapped at the air when flying as if it were catching insects though there were no real insects there.[9]

Weaver birds go through complicated nest building behaviour when there is no nest building material present.[10]

Sham dustbathing (sometimes referred to as "vacuum dustbathing") is a behaviour performed by some birds when kept in cages with little or no access to litter. During sham dustbathing, the birds perform all the elements of normal dust bathing, but in the complete absence of any substrate.[11][12][13] This behaviour often has all the activities and temporal patterns of normal dustbathing, i.e. the bird initially scratches and bill-rakes at the ground, then erects her feathers and squats. Once lying down, the behaviour contains four main elements: vertical wing-shaking, head rubbing, bill-raking and scratching with one leg. However, hens "dustbathing" on wire floors commonly perform this close to the feed trough where they can peck and bill-rake in the food.[14] Because it seems the birds appear to treat the feed as a dustbathing substrate, the term "sham dustbathing" is more appropriate.

Raccoons

Wild raccoons often investigate their food by rubbing it between their paws while holding the food underwater, giving the appearance of 'washing' the food (although the exact motivation for this behaviour is disputed). Captive raccoons sometimes perform these actions of 'washing' their food by rubbing it between their paws, even when there is no water available. This is most likely a vacuum activity based on foraging behaviour at shorelines.[15]

Calves

One vacuum activity that has been studied is 'tongue-rolling' by calves. Calves raised for 'white' veal are generally fed a milk-like diet from birth until they are slaughtered at about four months of age. The calves are prevented from consuming roughage such as grass or hay partly because the iron contained in such plant-based food would cause their muscles to assume a normal reddish colour instead of the pale colour that purchasers of this product demand. The diet, however, is unnatural because calves would normally start to forage and ruminate from about two weeks of age. When limited to a milky diet, some calves will spend hours per day in what appears to be 'vacuum grazing'. They extend the tongue out of the mouth and curl it to the side in what appears to be the action that cattle use to grasp a sward of grass and pull it into the mouth, but the calves do this simply in the air, without the tongue contacting any physical object.."[5]

Pigs

A similar vacuum activity to tongue rolling is 'vacuum chewing' by pigs. In this behaviour, pigs perform all the activities associated with chewing but with no substrate in their mouth. This abnormal behaviour can represent 52–80% of all stereotyped behaviours.[16]

See also

References

- Russell A. Dewey. "8: Animal Behavior and Cognition | The Contributions of Konrad Lorenz | Vacuum, Displacement, and Redirected Activities". Psychology: An Introduction.

- Paul Kenyon. "Explanation of Lorenz hydraulic model of motivation". www.flyfishingdevon.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Mench, Joy (1998-01-01). "Why It Is Important to Understand Animal Behavior". ILAR Journal. 39 (1): 20–26. doi:10.1093/ilar.39.1.20. ISSN 1084-2020. PMID 11528062.

- Animal Behavior Society (1996). Houck, Lynne D.; Drickamer, Lee C. (eds.). Foundations of animal behavior : classic papers with commentaries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-35456-3. OCLC 34321442.

- Fraser, David (2013). Understanding Animal Welfare The Science in its Cultural Context. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-69736-8. OCLC 894717497.

- Zumpe, Doris. (2001). Notes on the Elements of Behavioral Science. Michael, Richard P. Boston, MA: Springer US. ISBN 9781461512394. OCLC 840283643.

- Robinson, Gene E.; Barron, Andrew B. (2017-04-06). "Epigenetics and the evolution of instincts". Science. 356 (6333): 26–27. Bibcode:2017Sci...356...26R. doi:10.1126/science.aam6142. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28385970. S2CID 206656541.

- Bell, Ben; Wood, Ruth Laura (2003). Investigation of the Behavioural Response of a Colony of Group-Housed Hamadryas Baboons (Papio Cynocephalus Hamadryas) to Relocation to a More Naturalistic Enclosure. Victoria University of Wellington. OCLC 815851373.

- Lorenz, K. (1981-09-23). The Foundations of Ethology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783211816233.

- Edward M. Barrows (2000-12-28). Animal Behavior Desk Reference: A Dictionary of Animal Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-4200-3947-4.

- Olsson, I.Anna S; Keeling, Linda J; Duncan, Ian J.H (2002). "Why do hens sham dustbathe when they have litter?". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 76 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(01)00181-2. ISSN 0168-1591.

- Merrill, R. J. N.; Cooper, J. J.; Albentosa, M. J.; Nicol, C. J. (May 1, 2006). "The preferences of laying hens for perforated Astroturf over conventional wire as a dustbathing substrate in furnished cages". Animal Welfare. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. 15 (2): 173-178(6). doi:10.1017/S0962728600030256. S2CID 70845760.

- van Liere, D W (August 1, 1992). "The significance of fowls' bathing in dust". Animal Welfare. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. 1 (3): 187-202(16). doi:10.1017/S0962728600015001. S2CID 255767751.

- Lindberg, A.C.; Nicol, C.J. (1997). "Dustbathing in modified battery cages: Is sham dustbathing an adequate substitute?". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 55 (1–2): 113–128. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00030-0. ISSN 0168-1591.

- "Raccoon". Archived from the original on 2009-01-26. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- Robert, S; Bergeron, R; Farmer, C; Meunier-Salaün, M.C (2002). "Does the number of daily meals affect feeding motivation and behaviour of gilts fed high-fibre diets?". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 76 (2): 105–117. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00003-5. ISSN 0168-1591.