Rangea

Rangea is a frond-like Ediacaran fossil with six-fold radial symmetry.[2][3] It is the type genus of the rangeomorphs.

| Rangea Temporal range: Ediacaran ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

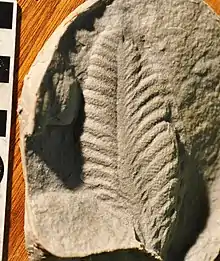

| Rangea scheiderhoehni from the Ediacaran Kliphoek Member of Dabis Formation on farm Aar, near Aus, Namibia. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Family: | † Rangeidae |

| Genus: | † Rangea |

| Type species | |

| Rangea schneiderhoehni Gurich 1929 | |

Rangea was the first complex Precambrian macrofossil named and described anywhere in the world. Rangea was a centimetre- to decimetre-scale frond characterised by a repetitive pattern of self-similar branches and a sessile benthic lifestyle. Fossils are typically preserved as moulds and casts exposing only a leafy petalodium, and the rarity and incompleteness of specimens has made it difficult to reconstruct the three-dimensional (3D) morphology of the entire organism.[4]

Fossilized Rangea consists of several vanes. Each vane has a foliate shape with a series of recessed furrows that run outwards at varying angles from a prominent smooth median zone to define a series of chevron-like units called quilts. The quilts are arranged in two rows, that is, as long petaliform primary quilts and short lanceolate subsidiary quilts. The subsidiary quilts pinch out a short distance from the median zone as the primary quilts expand whereas the primary quilts extend to the edge of the frond where they taper bluntly. In no specimen can an exact total of primary quilts be counted, on account of either missing areas or incomplete preservation. The apices of the quilts are sharply delimited by wedge-shaped fields of either smooth or wrinkled relief that give this part of the body a scalloped appearance.[5]

A total of six species have been described, but only the type species Rangea schneiderhoehoni is considered valid:

- R. brevior Gürich 1933 = R. schneiderhoehoni.

- R. arborea Glaessner et Wade, 1966 = Charniodiscus arboreus.

- R. grandis Glaessner et Wade, 1966 = Glassnerina grandis = Charnia massoni.

- R. longa Glaessner et Wade, 1966 = Charniodiscus longus.

- R. sibirica Sokolov, 1972 = Charnia sibirica = Charnia massoni.

Rangea schneiderhoehni fossils have been found in the Kanies and Kliphoek Members of the Dabis Formation and in the Niederhagen Member of the Nudaus Formation, Namibia. These deposits date from around 548 Mya. Rangea fossils have also been reported from the Ediacaran deposits of the Arkhangelsk region, Russia and in Australia. These fossils date from around 558-555 Mya.[2][3][6] Rangea seems to have led a sessile existence.[2]

New specimens provide evidence that Rangea was not a simple flexuous frond but a squat obconical fossil with radiating vanes which conjoin in a rather precise manner, so that the ridges corresponding to the axial traces on the branches on the reverse side of one frond exactly fit the depressions between the branches on the reverse side of the next, and the distal ends of the individual fronds meet virtually at a point. If the whole Rangea specimen is curved or deformed, then the same kind of curvature influences all its individual vanes. In one specimen, narrow wedges of sediment about 1–2 mm thick and some 5–6 mm deep penetrate the sutures between adjacent, conjoined fronds. This suggests that though it is usual for the lateral parts of the fronds to be tightly appressed and composite molded together, the individual fronds of the live organism were discrete structures, either largely or completely separate from those adjacent. The highly ordered, complex branching of the structural elements of the frond is a common characteristic and possibly reflects an unusual environmental parameter in early Ediacaran seas.[7]

Rangea likely had a rigid or semi-rigid skeleton-like structure that prevented buckling or compression and maintained integrity during life. Ediacaran-style preservation is thought to have been aided by microbial mats that covered the sea floor. The high abundance of quartz found within these specimens is consistent with infilling of the organism by detrital quartz and preservation in sandstone.[4]

Another peculiarity of Rangea is the clustering of several vanes into a closely packed compound structure. In each cluster all the constituent fronds demonstrate a similarity in quilt morphology and uniformity of quilt arrangement. Furthermore, these clusters maintain their integrity in winnowed specimens of Rangea. This implies certain stability and resistance of the cluster to mechanical stress. Rangea is reconstructed as an immobile benthic creature, whose body consisted of three closely packed trough-shaped fronds enveloped by a mucous sheath. Three-dimensional preservation and biostratinomy of the fossils suggest that in life Rangea was completely immersed into sand, and that the sand filled the cavities of the trough-shaped fronds. Living Rangea had a convex-down posture within the sediment, with the edges of all three vanes rising above sediment. Each frond consisted of two membranes, and the space between these membranes was inflated and fractally quilted. The quilts were probably hydrostatically supported. Composite moulding of the frond suggests that the quilt boundaries correspond to structures stiff enough to press through the integument.[5]

Gregory Retallack considered that Rangea is not a benthic shallow marine fossil comparable with a sea pen but an alga or fungus from tidal flat or fluvial environments,[8][9][10] however his theory about Ediacaran biota is controversial.[11][12][13]

References

- Chen, Zhe; Zhou, Chuanming; Xiao, Shuhai; Wang, Wei; Guan, Chengguo; Hua, Hong; Yuan, Xunlai (2014). "New Ediacara fossils preserved in marine limestone and their ecological implications". Scientific Reports. 4: 4180. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E4180C. doi:10.1038/srep04180. PMC 3933909. PMID 24566959.

- Vickers-Rich, P.; Ivantsov, A. Y.; Trusler, P. W.; Narbonne, G. M.; Hall, M.; Wilson, S. A.; Greentree, C.; Fedonkin, M. A.; Elliott, D. A.; Hoffmann, K. H.; Schneider, G. I. C. (2013). "Reconstructing Rangea: New Discoveries from the Ediacaran of Southern Namibia". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:2013JPal...87....1V. doi:10.1666/12-074R.1. S2CID 130820365.

- Ivantsov, A. Yu.; Leonov M. V. (2009). The imprints of Vendian animals - unique paleontological objects of the Arkhangelsk region (in Russian). Arkhangelsk. p. 91. ISBN 978-5-903625-04-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sharp, Alana C., Alistair R. Evans, Siobhan A. Wilson, and Patricia Vickers-Rich. "First Non-destructive Internal Imaging of Rangea, an Icon of Complex Ediacaran Life." Precambrian Research 299 (2017): 303-08. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2017.07.023

- Grazhdankin, Dima, and Adolf Seilacher. "A Re-examination of the Nama-type Vendian Organism Rangea Schneiderhoehni." Geological Magazine 142.5 (2005): 571-82. . doi:10.1017/S0016756805000920

- Dzik, J. (2002). "Possible ctenophoran affinities of the precambrian "sea-pen" Rangea". Journal of Morphology. 252 (3): 315–334. doi:10.1002/jmor.1108. PMID 11948678. S2CID 22844283.

- Jenkins, Richard J. F. "The Enigmatic Ediacaran (late Precambrian) Genus Rangea and Related Forms." Paleobiology 11.3 (1985): 336-55. doi: 10.1017/S0094837300011635

- Retallack, G.J. (2020). "Boron paleosalinity proxy for deeply buried Paleozoic and Ediacaran fossils". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 540 (1): 279–284. Bibcode:2020PPP...540j9536R. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109536. PMID 109536. S2CID 212771632.

- Retallack, G.J. (2019). "Interflag sandstone laminae, a novel sedimentary structure, with implications for Ediacaran paleoenvironmentss". Sedimentary Geology. 379: 60–76. Bibcode:2019SedG..379...60R. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2018.11.003. S2CID 135301261.

- Retallack, G.J. (1994). "Were the Ediacaran fossils lichens?". Paleobiology. 20 (4): 523–544. Bibcode:1994Pbio...20..523R. doi:10.1017/S0094837300012975. S2CID 129180481.

- Waggoner, B. M. (1995). "Ediacaran Lichens: A Critique". Paleobiology. 21 (3): 393–397. Bibcode:1995Pbio...21..393W. doi:10.1017/S0094837300013373. JSTOR 2401174. S2CID 82550765.

- Waggoner, B.; Collins, A. G. (2004). "Reductio Ad Absurdum: Testing The Evolutionary Relationships Of Ediacaran And Paleozoic Problematic Fossils Using Molecular Divergence Dates" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 78 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0051:RAATTE>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 8556856.

- Nelsen, M. (2019). "No support for the emergence of lichens prior to the evolution of vascular plants". Geobiology. 18 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/gbi.12369. PMID 31729136.

Further reading

- Glaessner, Martin F.; Wade, Mary 1966: The late Precambrian fossils from Ediacara, South Australia. Palaeontology 9 (4), pp. 599–628.

- Gürich, Georg 1930: Uber den Kuibisquarzit in Sudwestafrika, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft v.82: p. 637.