Valentine Bambrick

Valentine Bambrick VC (13 April 1837 – 1 April 1864) was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Valentine Bambrick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 April 1837 Cawnpore, India |

| Died | 1 April 1864 (aged 26) Pentonville Prison, London, England |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Unit | 60th Rifles 87th Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars | Indian Mutiny |

| Awards | Victoria Cross (forfeited) |

Bambrick was a son of the Army - his father, at least one uncle (after whom he was named), and his older brother John all served with the 11th Hussars (Prince Albert's Own).[1]

Early life

He was the son of John Thomas Bambrick (1790-1879) and Harriett Ann née Redlan (1795-1871). His older brother Pte John Thomas Bambrick (1832-1893) fought with the 11th Hussars (PAO) during the famous Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854 during the Crimean War.[2] In 1853 Valentine Bambrick joined the 60th Rifles at the age of 16. He was 21 years old and a private in the 1st Battalion, 60th Rifles (later The King's Royal Rifle Corps) during the Indian Mutiny when the following deed took place on 6 May 1858 at Bareilly, India. He and his company commander Lieutenant Cromer Ashburnham (1831-1917) were cornered and Bambrick was awarded the Victoria Cross for his acts, recorded in the London Gazette as:

For conspicuous bravery at Bareilly, on the 6th of May, 1858, when in a Serai, he was attacked by three Ghazees, one of whom he cut down. He was wounded twice on this occasion.[3]

This short citation gives little idea of the desperate hand-to-hand fighting Bambrick would have been involved in the narrow streets and alleys of Bareilly.[4]

End of military career

Bambrick was jailed in May 1859 - possibly for insubordination - and then again in July and November of the same year. When the 1st Battalion returned to the United Kingdom in 1860, it did so without Bambrick who may have been serving a further sentence in a military jail. He transferred to the 87th Regiment, which by 1862 was stationed at Curragh Camp in Ireland. In July 1862 Bambrick was back in jail and in March 1863 he received a sentence of 160 days for desertion. It seems likely that Bambrick had a problem with alcohol. He had arrived at Aldershot in November 1863 just prior to being discharged from the Army and within 24 hours found himself in trouble again - this time with the civilian authorities.[5]

Incident at Aldershot

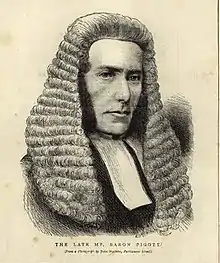

On 12 December 1863 Bambrick appeared at the Winchester Assizes before Mr. Justice Baron Pigott. There he and Charlotte Johnson were indicted for violently assaulting Henry Milner Russell (1828-1894), and stealing from his person four medals in Aldershot on 15 November 1863. Russell had married Eliza née Avery in 1861[6] and had been in Camp at Aldershot since at least the same year.[7]

Bambrick's version of the incident was that he had been passing the lodging-house in Pickford Street where Russell resided and had gone to the assistance of a prostitute calling "Murder!" who was being attacked by Lance-Corporal Henry Russell of the Commissariat Department. Russell was unable to fend off the stronger Bambrick and during the ensuing struggle Russell's medals fell from his breast. Bambrick claimed that after the fight he had picked these medals up and placed them on a mantlepiece, from where they disappeared. Bambrick stated he had no interest in Russell's medals as he himself had the Victoria Cross and the pension that went with it.[5][8][9]

However, the Court accepted Russell's version of events:

Mr H. T. Cole prosecuted. It appeared that the prisoners were standing at the door of a lodging house in Pickford Street, Aldershot, at night, on November 15. Russell, who was lance-corporal in the commissariat department, came up. Bambrick asked Russell to drink, and he took some beer out of his pint. They then went into Russell's room, who lodged in the house, and Russell said he would stand some beer, and he was in the act of giving the female prisoner some money to get the beer when Bambrick seized him by the throat, threw him on the bed, and tore from his breast four silver medals, one for the Punjab, one for the Sutlej, and one for the Crimea.

Russell called "Murder," and his cries were heard by some of the other soldiers, who rushed in and took Bambrick from off Russell, and he was conveyed to the guardhouse. Two of the medals were afterwards found in the passage, Russell was insensible, having been nearly choked. Bambrick made a long address to the jury. He stated that he had been in the service 10 years, and would have been discharged the day after the occurrence.

He had a pension of £10 a year, and, what was dearer to a soldier than any other medal, a Victoria Cross, but he would tell the jury the real facts.

On that night, as he was walking with the female prisoner towards this house, in which she also lodged, he heard cries of "Murder." He hastened and ran into the house, and saw a girl named Hayley coming out of Russell's room. She was crying, and said that Russell had beaten her and nearly strangled her. He went into the room and struck Russell, and they had a struggle together, and then the soldiers came in and took him up.

These facts he could have proved on the first day of the assizes, because then Hayley was in Winchester, but as she was what was called an "unfortunate," she could not afford to remain in Winchester.

The learned Judge having summed up, the jury found the prisoner guilty.

The Judge said he should defer passing sentence till the morning. Bambrick replied, "it is of no consequence what you do now. I don't care about losing my pension; but I have lost my position. I don't care what you do with me. You may hang me if you like".

This morning his Lordship passed sentence. He said, "Valentine Bambrick, I don't know that I ever had a more painful duty than in considering your case. I have felt great anxiety about it, and have considered everything you urged in your defence; but the evidence which satisfied the jury has satisfied me, and it does appear to me to be as clear a case as ever was tried. You say you had a witness, and that witness might have put some other construction on the matter. If you had made an application to have your trial postponed, I should have been the first to listen to your application, and I can't help thinking, from the intelligence you displayed, you must have been aware that you could have made such an application. I am bound to say that I don't think any witness could have altered the facts. You were found in a deadly struggle with another man. He was under you, and witness said that when he found you Russell was almost choked and suffocated by the pressure of your hand on his throat. It is perfectly clear he was robbed of his medals, and of them were found at the house where the woman lodged. How could they have come there? How did they come from the breast of Russell? I have no doubt you have exhibited great gallantry and great courage, and have well entitled yourself to the Victoria Cross. Had it not been for your character, I should have put in force the provisions of a recent statute and subjected you to personal castigation, but, as it, is I deal with your case with great regret. I should have been delighted if the jury could have seen their way to a doubt. I believe that you must have been under the influence of drink, for there was no adequate motive for your act, for the medals are only of trifling value.

Your punishment must be very severe. It must be penal servitude for three years.

With regard to you, Charlotte Johnson, you took a very subordinate part in the affair..”

Bambrick, holding up the girl's hand, said, "Look at this small hand, my lord; it is absurd to suppose she could have done much against a strong man. She was merely in the room."

The Judge replied, "l say she only took a subordinate part. I shall not punish her so severely as the male prisoner. She must be imprisoned, with hard labour, for 12 months".

Bambrick then shouted, "There won't be a bigger robber in England than I shall be when I come out".[10]

In reality, Russell's account of what had happened in Aldershot seems unlikely; his pride had probably been hurt at being soundly beaten by Bambrick and as a married man[7] he would not have been keen to explain either to his wife or his commanding officer that he had lost his medals while beating a prostitute in his room. However, Bambrick did not endear himself to the Court because of his confrontational manner, and despite Russell being the only witness for the prosecution Bambrick and Johnson were found guilty.[5]

Suicide

The Aldershot Military Gazette of 26 September 1863 recorded that:

"On Thursday a most determined attempt of suicide was made by a soldier named Valentine Bambrick, of the 87th Royal Irish Fusiliers, who, for some acts of gallantry was decorated with a Victoria Cross. It appears that in the course of the previous night (Wednesday), Bambrick was observed with a female in his room; was immediately apprehended, and conveyed to the guard-room. At about twelve o'clock the prisoner was being removed for the purpose of being brought before the commanding-officer, when seeing razor lying conveniently picked it up, and without the slightest hesitation drew it across his throat, inflicting a fearful gash. He then as rapidly drew the instrument down both sides of his chest, inflicting dangerous wounds. At this time the razor was wrested from him, and medical aid was at once summoned. Bambrick is now, we understand, doing as well as could be expected, and is likely to recover. The female, who was perhaps the cause of his committing the rash act, came with him from Ireland, and appears (as does the unfortunate fellow himself) very anxious for an interview. However, there is a strict guard kept over him, and as it is necessary that he should be kept extremely quiet, it is not probable she will have her liberty granted her, at present, at all events."

Valentine Bambrick had his Victoria Cross forfeited by Royal Warrant on 3 December 1863.[11] He was one of eight men who had their Victoria Cross forfeited, between 1856 and 1908, for various crimes. However, King George V felt that no Victoria Cross should ever be forfeited, regardless of crime. Bambrick and the other seven men whose awards were forfeited are officially listed as Victoria Cross holders.[12]

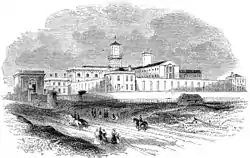

Valentine Bambrick committed suicide by hanging, using his pocket handkerchief from the handle of the ventilator behind the cell door in Pentonville Prison, London on 1 April 1864.[13]

"MELANCHOLY SUICIDE IN PENTONVILLE PRISON

An inquiry of a melancholy character was instituted by Dr. Lankester on Tuesday evening at the Pentonville Model Prison, relative to the death of a prisoner, Valentine Bambrick aged twenty-eight years (sic), who was found dead and hanging in his cell on Friday evening last. Last week a similar inquest was held. Mr Charles Lawrence Bradley, medical officer of the prison, said he had been told that he (prisoner) fretted, as he was being unjustly punished for a crime of which be was not guilty. His mind was no doubt impaired, and he had suffered from delirium tremens. A letter was written on slate by deceased which might be worth the attention of the jury He left a last letter, written, apparently, on slate, to his family."[14]

Bambrick's last letter read:

"My dear, dear Friends and Family, - Becoming quite tired of my truly miserable existence, I am about to rush into the presence of my Maker uncalled unasked. To you I appeal for forgiveness and pardon for all the unhappiness I have ever caused you. I dare not ask for mercy of God. I am doing that which admits of no pardon, but if He will hear my prayer. I pray to Him to grant you consolation in your hour of affliction, for I know that, notwithstanding all my faults, that love which you always manifested towards me is not withheld yet, and therefore the news of my unfortunate fate will make time sorrowful. Pray for your unfortunate son.

"VAL BAMBRICK."

P.S.-Before I die I protest solemnly my entire innocence of the charge for which I was punished, all but the assault, and that was done under the circumstances before mentioned to you in my letter. God bless you all Love to all my relations. Pity even while you condemn. Poor Val.[5][15]

Bambrick was buried in an unmarked grave in St Pancras and Islington Cemetery which could not be located, but a memorial plaque to him was placed in 2002. The location of his Victoria Cross is unknown.

Medal entitlement

Valentine Bambrick was entitled to the following medals:

![]()

![]()

| Ribbon | Description | Notes |

| Victoria Cross (VC) | 1858 | |

| Indian Mutiny Medal | 1858 | |

References

- Valentine Bambrick VC - The Comprehensive Guide to the Victoria and George Cross

- 1465 Pte John Thomas Bambrick, 11th Hussars - Lives of the Light Brigade - The E. J. Boys Archive

- "No. 22212". The London Gazette. 24 December 1858. p. 5513.

- Brian Best (2016). The Victoria Crosses that Saved an Empire: The Story of the VCs of the Indian Mutiny. Frontline Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4738-5709-4.

- Brian Izzard, Glory and Dishonour: Victoria Cross Heroes Whose Lives Ended in Tragedy or Disgrace, Amberley Publishing (2018) - Google Books

- Henry Milner Russell in the England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1837-1915 - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- 1861 England Census for Henry M Russell: Surrey, Aldershot, District Commissariat Department Aldershot Camps - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- Alan Whitworth, Yorkshire VCs, Pen & Sword Military (2012) - Google Books

- Neil R. A. Bell, Trevor Bond, Kate Clarke, M.W. Oldridge, The A-Z of Victorian Crime, Amberley Publishing (2016) - Google Books

- Proceedings of the Winchester Assizes - Saturday 12 December 1863 before Mr. Justice Baron Pigott against Valentine Bambrick VC

- Stewart, Iain. "Valentine Bambrick". Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "The Victoria Cross: Forfeiture". National Army Museum.

- GRO Register of Deaths: JUN 1864 1b 133 ISLINGTON - Valentine Bambrick

- MELANCHOLY SUICIDE IN PENTONVILLE PRISON Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1875) Fri 29 Jul 1864 Page 3

- Public Inquiry made by Dr. Lancaster at the Pentonville Model Prison, relative to the death of a prisoner named Valentine Bambrick

External links

- News Item "Memorial plaque erected to Valentine Bambrick"