Valeria Miani

Valeria Miani (1563 – 1620) was an Italian playwright noted for her works Celinda, a Tragedy, and Amorosa Speranza. Miani married Domenico Negri in 1593, with whom she had five children, Isabetta, Isabella, Lucretia, Giulio, and Anzolo.[1] Miani is known for being the first woman to publish a tragedy prior to the 18th century.[2] In addition, she was the third woman in Italy to write in the newly popular genre, the pastoral. Miani's works explored themes such as cross-dressing, death and punishment, female virtue, and female resilience.[3]

Valeria Miani | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1563 |

| Died | 1620 (aged 57) Unknown |

| Occupation | Playwright |

| Notable work | Celinda, a Tragedy and Amorosa Speranza |

| Spouse |

Domenico Negri (m. 1593–1613) |

| Children | Isabetta, Isabella, Lucretia, Guilio, and Anzolo |

| Parent |

|

Early life

Miani was born in the year 1563, most likely in the northern Italian city of Padua.[3]

Family

While it is unknown who Miani's mother was, Miani's father was Vidal Miani, a practicing Paduan lawyer. In addition to earning an income by practicing law, he also taught law, and rented rooms to students.[4] There is written record of Miani having two siblings, a brother who was a priest and a sister named Cornelia. Miani most likely had more siblings, as there would have been another son who would be the heir in the family. It would have been unlikely in this time period for a family to have their only son enter into the clergy, and have no son to continue the family line.[4]

Education

There is no written record of where Miani attended school. However, many young girls in this century were educated in convents, so it is possible that Miani was educated in a convent as well.[3] Miani did however, have contact with the Ricovrati of Padua, a society made up of intellectuals, and both foreign and domestic professors.[5] This academy was founded in 1599, and was the first academy to be established in Padua. Among its 25 founders was Galileo Galilei, famed Italian astronomer and philosopher. Decades after Valeria Miani had contact with the Ricovrati, the academy became known for its wide acceptance of women into its membership.[6] It is not known however, if the Ricovrati allowed women to become members in Miani's time, and if so, whether or not Miani was a member.

Marriage and family

Miani got married on September 22, 1593, at the age of 30. Her husband was Domenico Negri, a man whose occupation is unknown.[3] The formal ceremony was at the Church of the Eremitani, while the marriage contract was signed in the groom's home city of Venice. Compared to other women of a similar background in Italy during this time period, this was considered late in a woman's life to get married.[4] While this may have been late for a typical woman of Miani's background, it was not for women of Miani's occupation. Other female writers during this century were married late in their life as well. Venetian writer and poet Moderata Fonte married at the age of 27, while Venetian author and women's rights activist Lucrezia Marinella married at the age of 35.[4] Negri's death occurred sometime between the years 1612 and 1614. Following the time of his death, Miani no longer published anything else, seemingly ending her writing career.

Miani and her husband are known to have five children.[1] Their three daughters were Lucretia, Isabella, and Isabetta, and their two sons were Giulio ad Anzolo.

Death

Very little is known regarding the death of Valeria Miani. While it is known that she died in the year 1620, a specific date is not given.[7] The place of her death is not known either, though it is likely that she passed somewhere in her home country of Italy.

Works

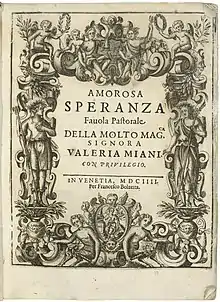

Amorosa Speranza

Miani's first pastoral drama, Amorosa Speranza was published in 1604.[8] It took Miani six years to have her play published, having submitted it to her publisher in 1598. Her publisher and editor Francesco Bolzetta had the play in his possession for years before he decided to put it into print.[9] Bolzetta was the primary publisher for the Ricovrati of Padua, the same academy which Miani was in contact with.[10] By publishing Amorosa Speranza, Miani became the third woman in Italy to have ever published a nonreligious play. The play Amorosa Speranza appears to have not been written for print, but rather for performance. Multiple times during the play the performer addresses the audience, even so much as having the prologue of the performance primarily spoken to the audience.[10] The plot of Amorosa Speranza revolves around the life of the virtuous sprite Venelia, who has been abandoned by her husband following their wedding night. Venezia struggles throughout the play to rid herself of the unwanted advances of two shepherds, Alliseo, and Isandro.[10]

In Amorosa Speranza, Miani shields her two main characters from the satyrs and their deviance by having a third nymph be the one to outsmart and trick the satyr. By this third nymph deceiving the satyr who would want to do her harm, she is emphasizing the independence and autonomy that her female characters have within the story.[3]

Celinda, A Tragedy

Miani's second published work, Celinda, a Tragedy, was published seven years after Amorosa Speranza, in 1611. The publishing of this play marked the first known tragedy written and published by an Italian woman.[10] Just as Amorosa Speranza was, Celinda, a Tragedy was published by the official publisher for the Ricovrati, Francesco Bolzetta.[3] During the time when Celinda was published, the tragedy genre was exploding in popularity, with approximately 60 new tragedies published in 1611.[6] While Celinda enjoyed popularity in print, there is no record of it ever making it to the stage.[1] This was due in part to the fact that audiences considered tragedies bad omens to watch. Additionally, these performances were very expensive to put on, due to the cost of hiring actors, and having to recreate the bloody and violent imagery detailed in the play. The plot of Celinda, a Tragedy follows the story of the title character, 15 year old princess Celinda, and her prohibited relationship with Persian prince Autilio.[1] Despite the fact that the two meet under false pretenses, with Autilio disguised as a woman, they fall in love. The entirety of the play details the horror and tragedy that befalls the two young lovers, complete with suicide and vendettas, both common motifs in the tragedy genre.[10]

References

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Finucci, Valeria; Kisacky, Julia (2010). Celinda, A Tragedy (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Center for Reformation and Renaissance. p. 11. ISBN 978-0772720757.

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Finucci, Valeria; Kisacky, Julia (2010). Celinda, A Tragedy (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Center for Reformation and Renaissance. p. 19. ISBN 978-0772720757.

- Rees, Katie (2014). "Satyr Scenes in Early Modern Padua: Valeria Miani'samorosa Speranzaand Francesco Contarini'sfida Ninfa". Italianist. 34 (1): 23–53. doi:10.1179/0261434013Z.00000000062. S2CID 191496061.

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Finucci, Valeria; Kisacky, Julia (2010). Celinda, A Tragedy (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Center for Reformation and Renaissance. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0772720757.

- "The Academy – Historical Facts". www.accademiagalileiana.it. Accademia Galileiana di Scienze Lettere ed Arti in Padova. 1 February 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Cox, Virginia (2011). The prodigious muse : women's writing in counter-reformation Italy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4214-0032-7.

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Finucci, Valeria; Kisacky, Julia (2010). Celinda, A Tragedy (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Center for Reformation and Renaissance. p. 12. ISBN 978-0772720757.

- Miani Negri, Valeria (1604). Amorosa speranza fauola pastorale della molto mag. Venetia: Francesco Bolzetta.

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Finucci, Valeria; Kisacky, Julia (2010). Celinda, A Tragedy (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Center for Reformation and Renaissance. p. 23. ISBN 978-0772720757.

- Rees, Katie (2008). "Female-Authored Drama in Early Modern Padua: Valeria Miani Negri". Italian Studies. 63 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1179/007516308X270128. S2CID 191361308.

Bibliography

- "The Academy - Historical Facts". Accademia Galileiana di Scienze Lettere ed Arti in Padova. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Bennett, Judith M.; Clark, Elizabeth A.; O'Barr, Jean F.; Vile, B. Anne; Westphal-Wihl, Sarah (1989). Sisters and workers in the Middle Ages (2. [Dr.]. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226042480.

- Cox, Virginia (2011). The prodigious muse : women's writing in counter-reformation Italy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0032-7.

- Cox, Virginia (2008). Women's writing in Italy, 1400-1650 ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8819-9.

- Jeffery, V. M. (January 1924). "Italian and English Pastoral Drama of the Renaissance: Source of the "Complaint of the Satyres against the Nymphes"". The Modern Language Review. 19 (1): 56–62. doi:10.2307/3713783. JSTOR 3713783.

- Leonard, Amy (2005). Nails in the wall : Catholic nuns in Reformation Germany. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226472574.

- Miani Negri, Valeria (1604). Amorosa speranza fauola pastorale della molto mag. Venetia: Francesco Bolzetta.

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Alexandra Coller (2020). Amorous Hope, A Pastoral Play: Bilingual Edition (1st ed.). The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series, 83. Toronto, Ontario: Iter Press. ISBN 978-1-64959-026-8 (paper); ISBN 978-64959-027-5 (pdf), ISBN 978-1-64959-034-3 (epub).

- Miani Negri, Valeria; Finucci, Valeria; Kisacky, Julia (2010). Celinda, A Tragedy (1st ed.). Toronto, Ontario: Center for Reformation and Renaissance. ISBN 978-0772720757.

- Rees, Katie (2008). "Female-Authored Drama in Early Modern Padua: Valeria Miani Negri". Italian Studies. 63 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1179/007516308X270128. S2CID 191361308.

- Rees, Katie (2014). "Satyr Scenes in Early Modern Padua: Valeria Miani'samorosa Speranzaand Francesco Contarini'sfida Ninfa". Italianist. 34 (1): 23–53. doi:10.1179/0261434013Z.00000000062. S2CID 191496061.

- Ufficio di Sanita. Registro dei Morti (1598-1618), sub indice. Busta 467, Archivo di Stato, Padua.