Vallader dialect

Vallader (Vallader, Sursilvan, Puter, Surmiran, and Rumantsch Grischun: vallader [vɐˈlaːdɛr] ⓘ; Sutsilvan: valader) is a variety of the Romansh language spoken in the Lower Engadine valley (Engiadina Bassa) of southeast Switzerland, between Martina and Zernez. It is also used as a written language in the nearby community of Val Müstair, where Jauer is spoken. In 2008, schools in the Val Müstair switched from Vallader to Rumantsch Grischun as their written language, but switched back to Vallader in 2012, following a referendum.

| Vallader | |

|---|---|

| vallader | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [vɐˈlaːdɛr] ⓘ |

| Region | Lower Engadine, Val Müstair |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | lowe1386 |

| IETF | rm-vallader[2] |

The name of the dialect is derived from val 'valley'. It is the second most commonly spoken variety of Romansh, with 6,448 people in the Lower Engadine valley (79.2%) naming Romansh as a habitually spoken language in the census of 2000.[3]

Romansh can be separated into two dialect groups: Rhine dialects (Sursilvan, Sutsilvan and Surmiran) and Engadine dialects (Vallader and Puter).[4]

A variety of Vallader was also used in Samnaun until the late 19th century, when speakers switched to Bavarian. The last speaker of the Romansh dialect of Samnaun, Augustin Heiß, died in 1935.[5]

For a long period of time, the oldest written form Puter held much prestige with its name. It was used as the language of the aristocratic Engadine tourist region near St. Moritz (San Murezzan). It was used most widely in the 19th century. Vallader has since become more important.[6]

The dialect Jauer, is actually a variety of Vallader spoken in Val Müstair. It is almost only spoken there, and is virtually never written.[7]

Classification

Puter and Vallader are sometimes referred to as one specific variety known as Ladin, a term which can also refer to the closely related language in Italy's Dolomite mountains also known as Ladin.

They are also considered Engadine dialects, since they are spoken in the area of the Engadines.

Vallader shares many traits with the Puter dialect spoken in the Upper Engadine. On the lexical level, the two varieties are similar enough to have a common dictionary.[8] Puter and Vallader share the rounded front vowels [y] and [ø], which are not found in other Romansh varieties. These sounds make written Ladin easily distinguishable through the numerous occurrences of the letters ⟨ü⟩ and ⟨ö⟩.[9]

Phonological differences

In Vallader, the clitics are almost always well preserved, and there are no clustered forms that are known. On the other hand, Puter still preserves the clitic system completely.[10]

Compared to Puter, Vallader spelling reflects the pronunciation more closely.

Another difference is that one class of verbs end in -ar in Vallader, whereas the ending in Puter is -er. The differences in verb conjugation are more divergent however, as can be seen in the simple present of avair 'to have':[8][11]

| Dialect | 1. Sg. | 2. Sg. | 3. Sg. | 1. Pl. | 2. Pl. | 3. Pl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puter | eau d'he | tü hest | el ho | nus avains | vus avais | els haun |

| Vallader | eu n'ha | tü hast | el ha | nus vain | vus vaivat/avaivat/avais | els han |

| Sursilvan | Vallader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | free | clitic | free | clitic |

| 1 sg | jeu | -u | eu | e, -a |

| 2 sg | ti | - | tü | - |

| 3 sg (masc.) | el | -'l | el | -'l |

| 3 sg (fem.) | ella | -'la | ella | -'la |

| 1 pl | nus | -s, -sa | nus/ no | -a |

| 2 pl | vus | - | vus/vo | - |

| 3 pl (masc.) | els | -i | els | i, al, -a |

| 3 pl (fem.) | ellas | las, -'las | ellas | i, al, -a |

Impersonals

In Vallader, impersonals are formed using a third person singular reflexive verbal clitic. This is an important detail derived most likely from Italian. This is also possible in Puter.[12]

| Dialect | Original | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Vallader | Passand tras il desert as chatta qualchevoutas skelets. | Crossing the desert, one sometimes finds skeletons. |

| Puter | Passand tres il desert chatta ün qualchevoutas skelets. | Crossing the desert, one sometimes finds skeletons. |

Geographic distribution

Vallader, being one of the five dialects, is mainly used in the Val Müstair and Engadine regions. The name comes from the term "valley" so it's only right that it is found in these regions full of valleys.

As you can see on the map provided below, Vallader is used much more widely to the North East of Graubünden. This distinct difference in blue shades shows the areas of Upper and Lower Engadines. The Lower Engadin, as the chart suggests, speaks Vallader. In the Upper Engadin, Puter is spoken.

A larger issue at hand for the minority Vallader speakers is not only the use of Bavarian, High and Swiss German, but also the division of Romansh. This is especially evident for speakers of the Vallader dialect; since Puter is so closely related in both location and language, it makes the slight differences more cumbersome.

Dialects

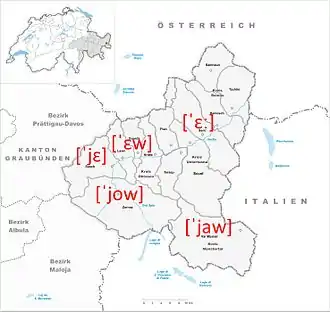

While written Vallader is standardized, speakers employ local dialects in oral use. Differences in speech often allow people to pinpoint the home village of another speaker. For example, the word eu 'I' can be pronounced as [ˈɛː], [ˈɛw], [ˈjɛ], [ˈjɐ], [ˈjow] and [ˈjaw], depending on the local dialect.[13]

The dialect of the Val Müstair, Jauer, is distinguished through the ending -er instead of -ar for verbs of the first conjugation, and by the placement of stress on the penultimate syllable of these verbs. In addition, stressed /a/ is diphthongized in Jauer. All three traits can be seen in the verb 'to sing', which is chantàr in Vallader but chàunter in Jauer.

It is an important fact to keep in mind that Jauer is almost exclusively spoken. Vallader is not only the preferred written form, but it is also the most widely used one.

Official status

As stated earlier, in 2008, schools in the Val Müstair switched from Vallader to Rumantsch Grischun as their written language. When they switched back to Vallader in 2012 following a referendum, it showed that Vallader is in danger but is still without a doubt seen as a (if not the most) reliable language, especially for writing. Since Jauer is used almost solely for speech, this allows more room for Vallader to exist as more of an entity in the world of writing.

It is the second most widely used variety of Romansh, with 6,448 people in the Lower Engadine valley (79.2%) naming Romansh as a habitually spoken language in the census of 2000.[3] This area is the main driving force behind keeping Vallader relevant.

Literature

The first written document in Vallader is the psalm book Vn cudesch da Psalms by Durich Chiampell from the year 1562.[14]

Other important authors who have written in Vallader include Peider Lansel, Men Rauch, Men Gaudenz, Andri and Oscar Peer, Luisa Famos, Cla Biert, Leta Semadeni and Rut Plouda-Stecher.

The songwriter Linard Bardill also employs Vallader in addition to German and Rumantsch Grischun.

Sample

The fable The Fox and the Crow by Jean de La Fontaine in Vallader, as well as a translation into English, the similar-looking but noticeably different-sounding dialect Puter, the Jauer dialect, and Rumantsch Grischun.[15]

| Vallader ⓘ |

Putèr ⓘ |

Rumantsch Grischun ⓘ |

Jauer | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La vuolp d'eira darcheu üna jada fomantada. Qua ha'la vis sün ün pin ün corv chi tgnaiva ün toc chaschöl in seis pical. Quai am gustess, ha'la pensà, ed ha clomà al corv: «Che bel cha tü est! Scha teis chant es uschè bel sco tia apparentscha, lura est tü il plü bel utschè da tuots». | La vuolp d’eira darcho üna vouta famanteda. Co ho'la vis sün ün pin ün corv chi tgnaiva ün töch chaschöl in sieu pical. Que am gustess, ho'la penso, ed ho clamo al corv: «Che bel cha tü est! Scha tieu chaunt es uschè bel scu tia apparentscha, alura est tü il pü bel utschè da tuots». | La vulp era puspè ina giada fomentada. Qua ha ella vis sin in pign in corv che tegneva in toc chaschiel en ses pichel. Quai ma gustass, ha ella pensà, ed ha clamà al corv: «Tge bel che ti es! Sche tes chant è uschè bel sco tia parita, lur es ti il pli bel utschè da tuts». | La uolp d'era darchiau üna jada fomantada. Qua ha'la vis sün ün pin ün corv chi tegnea ün toc chaschöl in ses pical. Quai ma gustess, ha'la s'impissà, ed ha clomà al corv: «Cha bel cha tü esch! Scha tes chaunt es ischè bel sco tia apparentscha, lura esch tü il pü bel utschè da tots» | The fox was hungry yet again. There he saw a raven upon a fir holding a piece of cheese in its beak. This I would like, he thought, and shouted at the raven: "You are so beautiful! If your singing is as beautiful as your looks, then you are the most beautiful of all birds.". |

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2022-05-24). "Romansh". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 2022-10-07. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- "Vallader idiom of Romansh". IANA language subtag registry. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Gross, Manfred (2004). Romanisch: Facts & Figures (PDF). Translated by Evans, Mike; Evans, Barbara. Chur: Lia Rumantscha. p. 31. ISBN 3-03900-037-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- Kotliarov, Ivan (2010). "The Elision of Unstressed Vowels Before the Latin Sequence /ka/ in Western Romance Languages". Folia Linguistica Historica. 44 (Historica vol. 31). doi:10.1515/flih.2010.004. S2CID 170455631.

- Ritter, Ada (1981). Historische Lautlehre der ausgestorbenen romanischen Mundart von Samnaun (Schweiz, Kanton Graubünden) [Historical phonology of the extinct Romansh dialect of Samnaun (Switzerland, Graubünden canton)] (in German). Gerbrunn bei Würzburg: Verlag A. Lehmann. p. 25.

- Posner, Rebecca; et al., eds. (1993). Bilingualism and Linguistic Conflict in Romance. Berlin: Moulton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-011724-X – via Google Books.

- Hack, Franziska Maria; Gaglia, Sascha (2009). "The Use of Subject Pronouns in Raeto-Romance: A Contrastive Study" (PDF). In Kaiser, Georg A.; Remberger, Eva-Maria (eds.). Proceedings of the Workshop "Null-Subjects, Expletives, and Locatives in Romance". Konstanz: Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft, Universität Konstanz. pp. 157–181.

- Peer, Oscar (1962). Dicziunari rumantsch ladin-tudais-ch. Chur: Lia Rumantscha.

- Liver, Ricarda (2010). Rätoromanisch: Eine Einführung in das Bündnerromanische [Rhaeto-Romanic: An introduction to Graubünden Romansh] (in German). Tübingen: Narr.

- Wanner, Dieter (2011). The Power of Analogy: An Essay on Historical Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018873-8 – via Google Books.

- Arquint, Jachen Curdin (1964). Vierv Ladin. Tusan: Lia Rumantscha.

- Anderson, Stephen R. (2006). "Verb Second, Subject Clitics, and Impersonals in Surmiran (Rumantsch)". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 32 (1): 3–21. doi:10.3765/bls.v32i1.3435.

- Liver, Ricarda (2010). Rätoromanisch: Eine Einführung in das Bündnerromanische (in German). Tübingen: Narr. p. 67.

- Blanke, Huldrych (1963). "Die vierfache Bedeutung Durich Chiampells" [The fourfold meaning of Durich Chiampell]. Zwingliana (in German). 11 (10): 649–662.

- Gross, Manfred (2004). Rumantsch: Facts & Figures (PDF). Translated by Evans, Mike; Evans, Barbara. Chur: Lia Rumantscha. p. 29. ISBN 3-03900-037-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

Literature

- Gion Tscharner: Dicziunari – Wörterbuch vallader-tudais-ch/deutsch-vallader Lehrmittelverlag Graubünden 2003. (Vallader-German dictionary)

- M. Schlatter: Ich lerne Romanisch. (Vallader), 9th edition 2003.

- G. P. Ganzoni: Grammatica ladina. Uniun dals Grischs und Lia Rumantscha 1983 (Vallader grammar written in French).