Value chain management capability

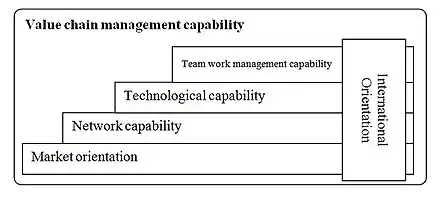

Value chain management capability refers to an organisation's capacity to manage the internationally dispersed activities and partners that are part of its value chain. It is found to consist of an international orientation, network capability, market orientation, technological capability and teamwork management capability. [1] Value chain management capability is a higher level capability that draws together a variety of lower level capabilities.

Overview

The elements of a company's value chain have been changing in the 21st century and the role of location in international business is changing (see e.g. Dunning 2000). Revolutionary developments in ICT (UNCTAD 2003) have profoundly reconstituted the nature of international business. Additionally, the importance of location is challenged by a ‘global shift’ (cf. Dicken 1998) in the economy. As multinationals have started to move their mobile assets globally to create a perfect fit with their immobile assets (UNCTAD 2003), their value chains have become disintegrated and scattered worldwide. The outcome is a ‘global factory’, a structure reflecting the combination of innovation, production and distribution of goods and services globally (Buckley 2009, Buckley and Ghauri 2004). These developments influence also small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). To survive, a firm must be capable of managing the internationally dispersed value creating operations effectively amidst an overload of information.

Dimensions of value chain management capability

The dimensions of value chain management capability presented below are based on a longitudinal case study. The empirical data was collected through a series of interviews with top managers in a globally operating technology-based SME.

International orientation - global mindset

The employees and the culture in the organization need to be internationally oriented, to have a global mindset (see Nummela et al. 2004). This includes most importantly the courage and enthusiasm to operate internationally. Moreover, hiring people with complementary language skills and different cultural backgrounds are also the most important. This may result in an organization that is tuned to global business: “It is not just about communicating, but actually co-operating with different people in different environments.”

Technological capability

The interviewees recognized a need to expand the pool of technological know-how through partnerships as a basic prerequisite for internationalization of software SMEs. If the R&D network is very small, the firm has to start searching for a new partner when facing new kinds of requirements. This is costly in terms of both time and money. In software, where the product life-cycles are short, the time to market is crucial. Therefore, a larger number of potential R&D partners gives the option of more rapidly choosing the best partner for innovative projects from existing network, and hence speeds up the development process (cf. Kim and Mauborgne 1997). Moreover, previous research asserts that innovativeness presumes also potential for creativity (DiLiello and Houghton 2008).

This study unveiled an additional aspect of technological capability. Strong technological know-how is not enough to fully utilize the technologies. To bring value to the customer, very good understanding of the specific area where the technology is used was seen necessary (cf. Rajala and Westerlund 2007). Thus, in addition to knowing the technology and having potential for creativity, technological capability includes also good knowledge of the context where the technology is applied. This links further to knowing the customer, and its business.

Market orientation & customer orientation

Market and marketing-related capabilities (Möller and Anttila 1987) are important for value chain management and the growing emphasis on services and software poses new requirements to marketing (cf. Vargo and Lush 2004). Market orientation appears to be crucial for steering the value chain effectively. Moreover, customer orientation was the most emphasized element of market orientation (see Narver & Slater 1990). (The technology-intensive nature of the business may have an influence here: Since the systems sold require customer contact before (specification etc.) and after sales (operational support and strategic care cf. Helander and Möller 2008), strong customer orientation is naturally necessary.)

Additionally, technology-based business, which focuses on system sales requires strong focus on marketing and partner training, because selling systems or solutions is more challenging than selling products (cf. Ruokonen et al. 2006). Finally, a well functioning market intelligence system is important to keep track of the markets. Moreover, when operating internationally, it is important to know each of the markets the firm operates in. However, this is not always possible, and therefore a network of partners is needed.

Network capability

A network of partners is the key to the scale and flexibility of the operations (cf. Ritter et al. 2002). The ability to approach potential partners with high success rate may be a critical factor in enabling a firm to achieve a position that is beneficial to it. Despite the benefits of networking, especially small firms face challenges with large partners. In the case of the partner being considerably larger firm, the small operator may not have any chance of actually influencing the partner organization. Through establishing good personal relations and frequent contacts to the managers in the larger value chain members they try to make sure the large partner remembers their existence and would turn to them when in need of the expertise they can provide.

Network capability includes both, management of individual partnerships as well as management of the whole network. Management of individual partnerships is however easily emphasized more than the management of the portfolio as a whole, and hence the portfolio of partnerships may be quite fragmented. In literature it is suggested that linking different parts of the value chain would be part of managing the chain, but the empirical data shows that it may be unachievable or even undesirable for small firms.

Team work management capability

In addition to the capabilities highlighted in earlier literature, effective utilization of virtual teams was brought up in the interviews. Working in virtual teams is common in many firms today. Proficient management enables intercultural teams to work well and to be productive. Furthermore, the employees must be tuned to teamwork in the sense that they see the benefits of doing things together. This can develop into an important organizational capability in SMEs, and thus enable global scale business with limited resources. It is moreover an important factor in the value chain management, as the internationally spread virtual teams coordinate and try to influence the operations of the value chain members.

Value chain management capability model

Internationality is an overarching theme in value chain management. Therefore, it is argued here that collective international orientation is the basis for value chain management capability. This is illustrated in the following figure.

International orientation penetrates all the other capabilities needed. Therefore, it seems that in addition to researchers also managers must take a holistic perspective to internationalization. Nonetheless, also other employees’ international orientation is important for executing the international operations in managing the value chain. Therefore, we argue that every employee must have a mindset that supports internationalization (cf. Levy et al. 2007).

The capabilities involved in value chain management are very much interlinked and overlapping. The fact that the elements go hand in hand supports the need to have an upper level construct of value chain management capability. When changes in one area affect also the other areas of the higher level capability, it is important to be aware of the big picture. Synthesizing the individual capabilities into the upper level construct gives a more extensive view of the phenomenon and enables indeed finding linkages between the capabilities.

The proposed model is based on seminal qualitative work. The concept of value chain management capability needs further development and more extensive research is required. This study provides interesting insights to this real-life phenomenon but it also points out that theoretically it would deserve additional attention. In further empirical research it would be interesting to conduct more of these holistic case studies to be able to analyze the phenomenon across cases. Additionally, extending the case study at hand to cover informants also from other organizations of the value chain could bring interesting new insights. Moreover, the development of a measure for value chain management capability requires much more work. Through further in-depth studies, it is possible to develop measures for rigorous testing. Since internationalizing value chains appear to be requisite for small firms in the software industry, and managing them very challenging, it is vital to know more about what makes it possible to succeed with them.

See also

References

- Eriksson, Taina; Nummela, Niina; Sainio, Liisa-Maija; Saarenketo, Sami (2017), Marinova, Svetla; Larimo, Jorma; Nummela, Niina (eds.), "Value Chain Management Capability in International SMEs", Value Creation in International Business: Volume 2: An SME Perspective, Springer International Publishing, pp. 171–193, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-39369-8_8, ISBN 978-3-319-39369-8, retrieved 2020-04-16

- DiLiello, T., Houghton, J. (2008) ‘Creative potential and practised creativity: Identifying untapped creativity in organizations’, Creativity and Innovation Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 37–46.

- Helander, A., Möller, K. (2008) ‘How to become a solution provider: System supplier’s strategic tools’, Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 247–287.

- Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (1997) ‘Value innovation: The strategic logic of high growth’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 75, No. 1, pp. 103–112.

- Levy, O., Beechler, S., Taylor, S., Boyacigiller, N.A. (2007) ‘What we talk about when we talk about ‘global mindset’: managerial cognition in multinational corporations’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 231–258.

- Möller, K., Anttila, M. (1987) ‘Marketing capability – A key success factor in small business?’, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 183–203.

- Narver, J.C., Slater, S.F. (1990) ‘The effect of a market orientation on business profitability’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 20–35.

- Nummela, N., Saarenketo, S., Puumalainen, K. (2004) ‘Global mindset – a prerequisite for successful internationalisation?’, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 51–64.

- Rajala, R., Westerlund, M. (2007) ‘Business models – a new perspective on firms' assets and capabilities: observations from the Finnish software industry’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 115–125.

- Ritter, T., Wilkinson, I.F., Johnston, W.J. (2002) ‘Measuring network competence: some international evidence’, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 17, No. 2/3, pp. 119–138.

- Ruokonen, M., Nummela, N., Puumalainen, K., Saarenketo, S. (2006) ‘Network management – the key to successful rapid internationalisation of a small software firm?’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 6, No. 6, pp. 554–572.

- Vargo, S.L., Lusch, R.F. (2004) ‘Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 1–17.