Vance Kirkland

Vance Hall Kirkland (November 3, 1904 – May 24, 1981) was a painter and educator in Denver, Colorado. His paintings, from 1926 to 1981, range from realist and impressionist watercolors, to surrealist deadwood worlds, to abstract expressionist mixtures of oil paint and water to richly textured dot paintings in oil. Commenting on Kirkland's works from 1954 to 1981, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, Vienna, Lóránd Hegyi, stated, “... in his later work, he developed a visionary art which mystically empathized with the entire universe, gave cosmic universality visual form in explosive images and used panel painting to convey the perpetually changing state of the universe.”[1] After his death Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art was founded in his name.

Vance Kirkland | |

|---|---|

Vance Kirkland in his Denver studio, 1957. Behind him is his 1956 painting Villa dei Misteri. | |

| Born | November 3, 1904 |

| Died | May 24, 1981 (aged 76) |

| Occupation | Painter |

Biography

Vance Hall Kirkland was born in Convoy, Ohio on November 3, 1904. Hall was his mother's maiden name, which he dropped after the first few years of painting. He attended the Cleveland School of Art, receiving a Diploma Degree of Painting (1927) and a Bachelor of Education in Art Degree (BEA, 1928), continuing a second year of studies in art history and art education at the Cleveland School of Education and Western Reserve University (1926–1928).[2]

Kirkland moved to Denver in 1929, where he remained for the rest of his life. He and Anne Fox Oliphant were married in 1941, enjoyed traveling together and entertaining. They remained married until Anne died in 1970. In addition to painting and teaching (detailed in the “Educator” section below), Kirkland volunteered his time for many institutions. Kirkland died May 24, 1981, in Denver.[3]

Career

Dianne Perry Vanderlip, Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, Denver Art Museum, knew Kirkland during the last three years of his life and was co-curator of the Vance Kirkland FIFTY YEARS retrospective. She noted: “...each of these periods, of course, has been tied together with a primary interest of communicating the human spirit’s adventure through time. Obviously, though he titles these paintings with space age titles—Nebula Near Saturn and that kind of thing—these are not science fiction paintings; these are paintings about the adventure of the human spirit.”[4]

Periods

Kirkland created about 1,200 paintings during his lifetime, spanning 5 painting periods and more than 30 series.[5] In the catalog for his 1978 retrospective exhibition at the Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado, Kirkland said, “It has been absolutely necessary for me to change directions in order to avoid repetition. Whenever a cycle of ideas seemed satisfactory, I knew I had done that and needed to move on and develop a greater challenge. Then the paintings remained fresh and were, I hoped, improved, and I avoided boredom.”[6]

One of the most important observations about Kirkland's career, made by museum scholars as documented below, is that he created something significant in each of his five painting periods. When his works were given exhibitions at 11 European museums and 2 exhibition halls, from 1997 to 2000, each of those 13 shows included all 5 of Kirkland's periods, ranging from the 1930s to the late 1970s.[7]

Red Rocks in April, c.1935, watercolor on paper, by Vance Kirkland. |

.jpg.webp) Ruins, Central City, 1940, watercolor on paper, by Vance Kirkland. |

1. Designed Realism (1926–1944): Vance Kirkland's first painting period, Designed Realism, consists of mostly watercolor and some oil paint. Lewis Sharp, Denver Art Museum Director, and former Curator, Metropolitan Museum, New York, stated, “…he handled this [watercolor] medium as well as any American artist ever has. You simply can go back and whether you want to begin with John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, or move to the 20th century with John Marin or Charles Burchfield, Vance Kirkland was a master.”[8] This period includes still lifes, portraits and landscapes.

.jpg.webp) Woden's Ring, 1945, watercolor and gouache on paper, by Vance Kirkland. |

.jpg.webp) Antipodean Garden, 1949, casein, tempera on panel, by Vance Kirkland. |

2. Surrealism (1939–1954): For his second painting period, Kirkland used mostly watercolor (also some gouache, casein, egg tempera and oil paint). He invented surrealist worlds of deadwood morphing into whimsical creatures, which dwarf pre-historic humans, scampering among the vegetation. Charles Stuckey, Curator of 20th Century Painting and Sculpture, The Art Institute of Chicago, commented, “...they show a virtuosity in his control of shape and transparency with the watercolor medium, that enables him to do in watercolor what artists like [René] Magritte and [Salvador] Dalí would be doing in oil at the same time...”[9]

Elizabeth Broun, former Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, further discussed this period: “I find in his surrealist works a charming willingness to contemplate nature as a positive force and evolution as a series of potentials. I think it comes out later in the nebula and dot paintings which give a sense of explosions in space. It’s a release of energy as a magnificent act of creation.”[10] “Some of his landscapes have proto-creatures, little animal forms and shapes, biomorphic, evolutionary beings. These sometimes include more or less recognizable little humanoid figures. You sense that he is putting man in his place in nature, showing him as just one of the potential evolutionary paths nature might have taken. It’s Kirkland’s way of reducing man back to the scale he may have felt was appropriate.” [11]

.jpg.webp) Timberline Abstraction, 1953, oil on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

.jpg.webp) Rocky Mountain Abstraction, 1947, gouache on paper, by Vance Kirkland. |

3. Hard Edge Abstraction/Abstractions from Nature (1947–1957): For his third painting period, Kirkland mostly did hard-edge painting in an abstract way. About half of these paintings are watercolor, half oil. This period includes the Timberline Abstraction series [example from 1953 shown above]. Charles Stuckey analyzed part of this period: “There is a sense of labyrinth about his line, for example, that is obvious in these timberline abstract paintings—which are ostensibly developed from his meditations on leaves that he would see on the forest floor....some of the early attempts by him to achieve texture look like that wood grain that would obsess him and appear in everything, that one would associate with a table top, then with a sort of still life arranged on it, but a still life that went away and only left these incredible tracings.”[12]

.jpg.webp) The Energy of Space, 1959, oil paint and water on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

.jpg.webp) Asian Dancing Forms, 1963, oil paint and water with gold leaf on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

4. Abstract Expressionism (1950–1964): For his fourth painting period, Kirkland invented an abstract expressionist technique of mixing oil paint and water together, creating painting surfaces different than any other artist. Richard Brettell, Director, Dallas Museum of Art, discussed these paintings, “They were painted in the ‘50s and early ‘60s and are a part of the principal contribution of Vance Kirkland to the history of Abstract Expressionism in America....he was making use of the surface of the painting as a kind of battleground between oil and water, these two media liquids that resist each other, and creating these incredible sort of symphonies of color and battles of media that are in many ways interestingly comparable to what was going on in New York and much more powerful visually.”[13]

There are four main series: Nebulae Abstractions; Roman Related Abstractions; Asian Related Abstractions; Pure Abstractions.[14] Elizabeth Broun commented, “For my own feelings, the ideas about space, about time, about nebula, about becoming, about creation were fabulously expressed in the ‘50s and early ‘60s...I suspect that the nebula will emerge as an important aspect of his career.”[15]

Charles Stuckey discussed Kirkland's Roman and Asian Abstractions from this fourth period, “Kirkland traveled widely around the world in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s and brought to the grimy and colorless, dirty, abstract expressionist school a whole variety of color experiences that went way beyond the streets of Manhattan: from the deep red colors of Pompeii and Herculaneum—the wall paintings that he saw there—to the lacquer surfaces of art that he saw in the Far East.”[16]

_(1970).jpg.webp) Vibrations of Two Blues, Green and Violet on Yellow (Einstein Series), 1970, oil on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

Experience of Mysteries in Space, 1973, oil paint and water on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

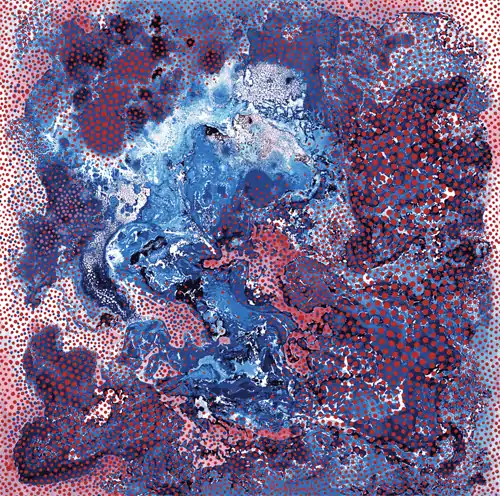

5. The Dot Paintings (1963–1981): For the paintings of his fifth and last period, Kirkland used wooden dowels to place dots of oil paint in various sizes and colors over an interactive background of forms of oil paint and water mixtures (or sometimes, instead, a color gradation background, also done in oil). He invented this technique which appears very different than Pointillism or the Ben-Day Dots of artist Roy Lichtenstein.[17] Péter Fitz, director of the Kiscelli Múzeum, Budapest, stated, “A highly unique period ensued, the long series of ‘Dot Paintings’. ... This technique might remind one of Pointillism, but only in theory, not in practice...this method is far from that of the Pointillists. The big, organic forms are built up from tiny dots, using powerful, sometimes brutal colors ... The dots of paint are plastic; they protrude from the surface of the painting, almost transforming it to a relief.” [18]

There are four main series and some important sub-series: Energy of Vibrations in Space [with sub-series Valhalla, Geometric, Einstein, Open Suns]; Energy of Mysteries in Space; Energy of Explosions in Space; Energy of Forces in Space; and occasionally Pure Abstractions.[19]

Charles Stuckey discussed these Dot Paintings, “Kirkland’s last paintings are remarkable. ... he achieved a kind of intensity that otherwise one associates in the history of art with, not only the Orphism and Futurism of the early 20th century, but the madness of Van Gogh. ... Kirkland obviously, from the beginning of his career in the late 1920s, very much wanted to paint like nobody else ever had—and he actually managed to do it.”[20]

Richard Brettell pointed out how appropriate the subject and often the titles about “energy” are to the paintings: “... the most vital paintings of his career and the paintings that really, in many senses, sum up his career were painted at the very end of his life when he was really ill, and you would never know that from looking at them. In back of me is a painting which he made in 1977, only four years before his death. It’s a painting which is immense in its scale, which has a kind of chromatic intensity almost unmatched in 20th century art, which is full of energy—of a chromatic energy and of energy of design ...”[21]

.jpg.webp) The Energy of Explosions Twenty-Four Billion Years B.C., 1978, oil paint and water on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

Explosions on a Sun 15 Billion Light Years from Earth, 1980, oil paint and water on linen, by Vance Kirkland. |

Kirkland and synesthesia

Kirkland derived many of his color combinations for his paintings through his synesthetic ability to sense color in music, especially classical compositions. In a 1978 interview with the Denver Art Museum he stated, “I have always interpreted sound as color. Mahler, Schoenberg, Bartok, Berg, Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Ives all explored new tonalities that aided me in transposing sounds into colors.” [22] Although he could derive colors from the music of most composers, he wanted a certain amount of musical dissonance which would give him the desired vibrating color combinations for his paintings, hence his interest primarily in modern composers.

Kirkland would listen to musical compositions at home, writing notes on scraps of paper when he heard passages that produced ideas for color schemes in his paintings. He would then go to his studio and employ those combinations of colors, which augmented his own imagination, in his paintings. Kirkland did not simultaneously paint while playing music because he would have been hearing other colors. Later, after he had created about 20% of the painting and had established the dominant colors, he could listen to music which he enjoyed so much.

Other famous people with synesthesia include artist David Hockney, composer and band leader Duke Ellington, author Vladimir Nabokov, physicist Richard Feynman and composer Franz Liszt.

Exhibitions and collections

Kirkland is documented as having 316 exhibitions from 1927 to 2000, in 76 American cities, 31 states, 17 foreign cities and 12 foreign countries. Of those exhibitions, 159 were at museums and 49 were at universities.[23]

Dianne Perry Vanderlip discussed Kirkland's exhibition history: “By 1946, he started his 12-year relationship with the prestigious Knoedler & Company gallery in New York where he received several solo shows and participated in many important group shows. He shared exhibitions with the master surrealist, Max Ernst, whom he deeply admired. ... Kirkland was included in the great exhibitions of Abstract and Surrealist American Art at The Art Institute of Chicago in 1947 and the Reality and Fantasy show at the Walker Art Center (Minneapolis) in 1954. Also during and after World War II, his work was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Denver Art Museum, the Worcester Art Museum (Massachusetts), the Moore Institute in Philadelphia...and many other important venues.”[24]

Museums that have Kirkland works in their permanent collections include the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, DC); Museum of Modern Art, Vienna; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest (Szépmüvészeti Muzeum); The Art Institute of Chicago; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, Missouri); Detroit Institute of Arts; New Mexico Museum of Art; and many others.[25]

Educator

Kirkland was the Founding Director and Professor of Art of the current University of Denver School of Art from 1929 to 1932, and again from 1946 until his retirement in 1969. From 1932 to 1946, Kirkland ran the Kirkland School of Art at 1311 Pearl Street.[26] His classes were “accredited by the University of Colorado in 1933”—thereby “initiating the art program at the University of Colorado Extension Center in Denver [now UCD] and had exchange classes with that institution.”[27] Thus Kirkland founded three art schools by the age of 28.

Kirkland Museum

In 1996, 15 years after Kirkland's death, the Vance Kirkland Foundation was established to preserve the works of Kirkland and other Colorado artists. In 2003, Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art opened in Denver to further that mission and to display Colorado and regional fine art along with an international decorative art collection spanning from the Arts & Crafts movement, Aesthetic, Art Nouveau, Glasgow Style, Wiener Werkstätte, De Stijl, Bauhaus, Art Deco, Modern, to Pop Art and Postmodern.

Kirkland Museum opened March 10, 2018 in a new 38,500-square-foot building, designed by Jim Olson of Seattle-based Olson Kundig and funded by Merle Chambers Fund. The new location is at 1201 Bannock Street in Denver's Golden Triangle Creative District.

Vance Kirkland's studio and art school building is the heart of the Kirkland Museum experience. On Sunday, November 6, 2016, in partnership with Mammoth Moving & Rigging Inc. and Shaw Construction, the three-room Vance Kirkland studio building was moved through the neighborhood via eight sets of remote-controlled articulating wheels to its new home eight blocks west at 12th & Bannock, where it is part of the new Kirkland Museum.

References

- Dr. Lóránd Hegyi, Vance Kirkland Paintings (Valencia, Spain: Sala Parpalló, Centre Cultural La Beneficència, 1999), 65. Dr. Lóránd Hegyi was Director of the Museum of Modern Art, Vienna from 1990 to 2001, at the time of the quote.

- Hugh A. Grant, “Mysteries in Space: Discussions with Vance Kirkland,” in Vance Kirkland MYSTERIES IN SPACE (New York: Genesis Galleries Ltd., 1978), 60, 74.

- Peter Weiermair, ed., Vance Kirkland (Zurich & New York: Edition Stemmle, 1998), 153.

- Emmerich Oross, Producer & Director; Dianne Perry Vanderlip speaking in Vance Kirkland’s Visual Language, an hour television documentary for PBS stations (Denver, CO: KRMA-TV, Denver [now Rocky Mountain PBS], 1994), DVD. Dianne Perry Vanderlip served as Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Denver Art Museum from 1978 to 2007.

- Hugh A. Grant "Part II: Individual Periods of Paintings." In Vance Kirkland Retrospective ed. Yevgenia Petrova. (Saint Petersburg, Russia: State Russian Museum, 2000). 178–212.

- Lewis Story and Dianne Perry Vanderlip, “An Interview with Vance Kirkland,” in Vance Kirkland FIFTY YEARS (Denver, CO: The Denver Art Museum, 1978), 13.

- Catalogs were produced in nine languages and always English, with illustrations of the paintings (varying from 1930–1978 to 1929–1981).

- Vance Kirkland Painting (Kaunas, Lithuania: M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 1997) 34. Lewis Sharp was the Denver Art Museum Director at the time of the quote.

- Vance Kirkland Painting (Kaunas, Lithuania: M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 1997) 37. Dr. Charles Stuckey was Curator of 20th Century Painting and Sculpture at The Art Institute of Chicago at the time of the quote.

- Dr. Elizabeth Broun, “The Paintings of Vance Kirkland,” in Paintings of Vance Kirkland (Riga, Latvia: Foreign Art Museum, 1998), 91. Dr. Elizabeth Broun is the Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and was at the time of the quote

- Dr. Elizabeth Broun, “The Paintings of Vance Kirkland,” in Paintings of Vance Kirkland (Riga, Latvia: Foreign Art Museum, 1998), 92. Dr. Elizabeth Broun is the Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and was at the time of the quote.

- Vance Kirkland Painting (Kaunas, Lithuania: M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 1997) 37. Dr. Charles Stuckey was Curator of 20th Century Painting and Sculpture at The Art Institute of Chicago at the time of the quote.

- Emmerich Oross, Producer & Director; Dr. Richard R. Brettell speaking in Vance Kirkland’s Visual Language, an hour television documentary for PBS stations (Denver, CO: KRMA-TV, Denver [now Rocky Mountain PBS], 1994), DVD. Dr. Richard R. Brettell was Director of the Dallas Museum of Art at the time of the quote. In 1980, Dr. Brettell was appointed Searle Curator of European Painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1988, he became the McDermott Director of the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA). As of 2014, he is Margaret M. McDermott Distinguished Chair of Art and Aesthetic Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas.

- Hugh A. Grant, “IV. (4th Period) Floating Abstractions (1951–1964) (Abstract Expressionism),” in Vance Kirkland Retrospective, ed. Yevgenia Petrova (St. Petersburg, Russia: The State Russian Museum, 2000), 190-199.

- Vance Kirkland Painting (Kaunas, Lithuania: M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 1997) 40. Dr. Elizabeth Broun is the Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and was at the time of the quote.

- Vance Kirkland Painting (Kaunas, Lithuania: M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 1997) 40. Dr. Charles Stuckey was Curator of 20th Century Painting and Sculpture at The Art Institute of Chicago at the time of the quote.

- Pointillist dots are made with dabs of a brush; Lichtenstein made dots using metal screens and stencils.

- Péter Fitz, Vance Kirkland (Budapest, Hungary: Kiscelli Múzeum, 1997), 11.

- Hugh A. Grant, “V. (5th Period) THE DOT PAINTINGS (1963-81)—Energy in Space Abstractions,” in Vance Kirkland Retrospective, ed. Yevgenia Petrova (St. Petersburg, Russia: The State Russian Museum, 2000), 199-211.

- Vance Kirkland Painting (Kaunas, Lithuania: M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 1997) 41. Dr. Charles Stuckey was Curator of 20th Century Painting and Sculpture at The Art Institute of Chicago at the time of the quote.

- Emmerich Oross, Producer & Director; Dr. Richard R. Brettell speaking in Vance Kirkland’s Visual Language, an hour television documentary for PBS stations (Denver, CO: KRMA-TV, Denver [now Rocky Mountain PBS], 1994), DVD.

- Lewis Story and Dianne Perry Vanderlip, “An Interview with Vance Kirkland,” in Vance Kirkland FIFTY YEARS (Denver, CO: The Denver Art Museum, 1978), 33.

- “Vance Kirkland Exhibition History,” in Vance Kirkland Retrospective, ed. Yevgenia Petrova (St. Petersburg, Russia: The State Russian Museum, 2000), 220-230. Two additional exhibitions listed 28-page pamphlet, Vance Kirkland (Denver: Kirkland Museum, 2000) which has a complete list of the European exhibitions 1997–2000. When a show is listed over several years, it is counted as one.

- Dianne Perry Vanderlip, “Vance Kirkland: A Painter’s Journey,” in Vance Kirkland, ed. Peter Weiermair (Zurich & New York: Edition Stemmle, 1998), 17. Dianne Perry Vanderlip served as Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Denver Art Museum from 1978 to 2007.

- “Vance Kirkland Works in Public and Corporate Collections,” in Vance Kirkland Retrospective, ed. Yevgenia Petrova (St. Petersburg, Russia: The State Russian Museum, 2000), 230-231.

- Lewis Story and Dianne Perry Vanderlip, Vance Kirkland FIFTY YEARS (Denver, CO: The Denver Art Museum, 1978), 41.

- Hugh A. Grant, “Mysteries in Space: Discussions with Vance Kirkland,” in Vance Kirkland MYSTERIES IN SPACE (New York: Genesis Galleries Ltd., 1978), 62.