Veneti (Gaul)

The Venetī (Latin: [ˈwɛnɛtiː], Gaulish: Uenetoi) were a Gallic tribe dwelling in Armorica, in the northern part of the Brittany Peninsula, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

A seafaring people, the Veneti strongly influenced southwestern Brittonic culture through trading relations with Great Britain. After they were defeated by Junius Brutus Albinus in a naval battle in 56 BC, their maritime commerce eventually declined under the Roman Empire, but a prosperous agricultural life is indicated by archaeological evidence.[1]

Name

They are mentioned as Venetos by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC), Livy (late 1st c. BC) and Pliny (1st c. AD),[2] Ouénetoi (Οὐένετοι) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD) and Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[3] Veneti on the Tabula Peutingeriana (5th c. AD),[4] and as Benetis in the Notitia Dignitatum (5th c. AD).[5][6]

The ethnonym Venetī is a latinized form of Gaulish Uenetoi, meaning 'the kinsmen' or 'the friendly ones', possibly also 'the merchants'. It derives from the stem *uenet- ('kin, friendly'), itself a derivative of Celtic *weni- ('family, clan, kindred'; cf. OIr. fine; OBret. guen), ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *wenh₁- ('desire'; cf. Germ. *weniz 'friend').[7][8][9] The Gaulish name is cognate with many other ethnic names found in ancient Europe, such as the Venedoti (> Gwynedd), the Adriatic Veneti, the Vistula Veneti (> Wendes), and the Eneti.[10]

The city of Vannes, attested c. 400 AD as civitas Venetum ('civitas of the Veneti'; Venes in 1273) is named after the Gallic tribe.[11]

Geography

The Veneti built their strongholds on the tips of coastal spits or promontories, where shoals make approaching the headlands by sea dangerous, an unusual position which sheltered them from sea-borne attack.[12]

They inhabited southern Armorica, along the Morbihan bay. Their most notable city, and probably their capital, was Darioritum (now known as Gwened in Breton or Vannes in French), mentioned in Ptolemy's Geography. Other ancient Celtic peoples historically attested in Armorica include the Redones, Curiosolitae, Osismii, Esubii and Namnetes.

History

Coming of Caesar

Caesar reports in Bellum Gallicum that he sent in 57 BC his protégé, Publius Crassus, to deal with coastal tribes in Armorica (including the Veneti) in the context of a Roman invasion of Britain planned for the following year, which eventually went astray until 55.[13] Although Caesar claims that they were forced to submit to Roman power, there is no evidence of an initial opposition from the Gallic tribes, and the fact that Caesar sent only one legion to negotiate with the Veneti suggests that no trouble was expected. Caesar's report is probably part of a political narrative that was set up to justify the conquest of Gauls and to downplay his aborted plan to invade Britain in 56.[14] The scholar Michel Rambaud has argued that the Gauls initially thought they were making an alliance with the Romans, not surrendering to them.[13]

In 56 BC, the Veneti captured the commissaries Rome had sent to demand grain supplies in the winter of 57–56, in order to use them as bargaining chips to secure the release of the hostages they had previously surrendered to Caesar. Hearing of the nascent revolt, all the coastal Gaulish tribes bound themselves by oath to act in concert. This is the cause explicitly given by Caesar for the war.[15] This version is contradicted by Strabo, who contends that the Veneti aimed to stop Caesar's planned invasion of Britain, which would have threatened their trade relations with the British island. Strabo's claim appears to be confirmed by the participation in the war of other Gallic tribes involved in trade with Britain, and by the involvement of Britons themselves.[16]

Caesar had left for Illyricum at the beginning of the winter of 57–56. Informed of the events occurring in Armorica by Crassus, he launched the construction of a fleet of galleys, and placed orders for ships from the Pictones, Santones, and other 'pacified tribes'. War preparations were quickly achieved, and Caesar joined the Roman army 'as soon as the season permitted'. In response, the Veneti summoned help for further groups, including the Morini, Menapii and Britons.[15]

Given the highly defensible nature of the Veneti strongholds, land attacks were frustrated by the incoming tide, and naval forces were left trapped on the rocks when the tide ebbed. Despite this, Caesar managed to engineer moles and raised siege-works that provided his legions with a base of operations. However, once the Veneti were threatened in one stronghold, they used their fleet to evacuate to another stronghold, obliging the Romans to repeat the same engineering feat elsewhere.

Julius Caesar's victories in the Gallic Wars, completed by 51 BC, extended Rome's territory to the English Channel and the Rhine. Caesar became the first Roman general to cross both bodies of water when he built a bridge across the Rhine and conducted the first invasion of Britain.

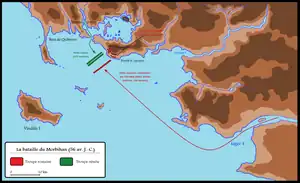

Battle of Morbihan

Since the destruction of the enemy fleet was the only permanent way to end this problem, Caesar directed his men to build ships. However, his galleys were at a serious disadvantage compared to the far thicker Veneti ships. The thickness of their ships meant they were resistant to ramming, whilst their greater height meant they could shower the Roman ships with projectiles, and even command the wooden turrets which Caesar had added to his bulwarks. The Veneti manoeuvred so skilfully under sail that boarding was impossible. These factors, coupled with their intimate knowledge of the coast and tides, put the Romans at a disadvantage. However, Caesar's legate Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus was given command of the Roman fleet, and in a decisive battle, succeeded in destroying the Gaulish fleet in Quiberon Bay, with Caesar watching from the shore. Using long billhooks, the Romans struck at the enemy's halyards as they swept past (these must have been fastened out-board), having the effect of dropping the huge leather mainsails to the deck, which crippled the vessel whether for sailing or rowing. The Romans were at last able to board, and the whole Veneti fleet fell into their hands.

Economy

According to Caesar, the Veneti were the most influential tribe of Armorica, since they had the largest fleet, which they used for trade with Britain, and they controlled a few harbours on the dangerous coasts of that region. This claim is evidenced by the fact that two officers (rather than one) were sent by the Romans to demand grain from them in the winter of 57–56 BC.[15] The Veneti had trading stations in Britain and regularly sailed to the island, and they charged customs and port dues on trade ships as they passed through the region. Strabo suggests that they were also using the terrestrial routes and rivers of Armorica to trade with Britain.[17]

These Veneti exercise by far the most extensive authority over all the sea-coast in those districts, for they have numerous ships, in which it is their custom to sail to Britain, and they excel the rest in the theory and practice of navigation. As the sea is very boisterous, and open, with but a few harbours here and there which they hold themselves, they have as tributaries almost all those whose custom is to sail that sea.

— Caesar, Bellum Gallicum, III (transl. H. J. Edwards, Loeb Classical Library, 1917)

Archaeological evidence show a shift in trade with Britain from Armorica to the more north-easterly routes during the second half of the 1st century BC, following the Roman decisive victory over Gaulish Armorican tribes in 56 BC.[18]

The Veneti built their ships of oak with large transoms fixed by iron nails of a thumb's thickness. They navigated and powered their ships through the use of leather sails. This made their ships strong, sturdy and structurally sound, capable of withstanding the harsh conditions of the Atlantic. They controlled the tin trade from mining in Cornwall and Devon.

Relationship with other tribes

Recently a study in France has shown that there is a remarkable correlation between the geographical distribution of a genetic disease (Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia (ARVD)) and the different Venetian settlement sites: Vistula basin, Adriatic Gulf and Armorican Massif in particular. This highlights the migratory flow of this people through the ages from their initial settlement site in near the Black Sea.[19]

Citations

- Drinkwater 2016.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:34, 3:7:4; Livy. Periochae, 104; Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:107.

- Strabo. Geōgraphiká, 4:4:1; Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:8:6.

- Tabula Peutingeriana, 1:2.

- Notitia Dignitatum, oc. 37:5.

- Falileyev 2010, s.v. Veneti.

- Lambert 1994, p. 34.

- Delamarre 2003, pp. 312–313.

- Matasović 2009, p. 413.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 312.

- Nègre 1990, p. 158.

- Erickson 2002, p. 602.

- Levick 2009, p. 63.

- Levick 2009, p. 67.

- Levick 2009, p. 64.

- Levick 2009, p. 65.

- Levick 2009, p. 66.

- Levick 2009, p. 69.

- http://www.realites-cardiologiques.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2011/03/Hebert.pdf

General and cited references

- Cunliffe, Barry W. (1988). Greeks, Romans, and Barbarians: Spheres of Interaction. Methuen. ISBN 978-0-416-01991-9.

- Cunliffe, Barry W. (1999). The Ancient Celts. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-025422-8.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Drinkwater, John F. (2016). "Veneti (1), Gallic tribe". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6723. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

- Erickson, Brice (2002). "Falling Masts, Rising Masters: The Ethnography of Virtue in Caesar's Account of the Veneti". American Journal of Philology. 123 (4): 601–622. doi:10.1353/ajp.2003.0004. ISSN 1086-3168. S2CID 154212032.

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.

- Levick, Barbara (2009). "The Veneti Revisited: C.E. Stevens and the tradition on Caesar the propagandist". In Welch, Kathryn; Powell, Anton (eds.). Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter: The War Commentaries as Political Instruments. Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-1-910589-36-6.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.

Further reading

- Loicq, Jean (2003). "Sur les peuples de nom «vénète» ou assimilé dans l'Occident européen". Études celtiques. 35 (1): 133–165. doi:10.3406/ecelt.2003.2153.

- Merlat, Pierre (1981). Les Vénètes d'Armorique. Ed. Archéologie en Bretagne. OCLC 604092636.