Vergence

A vergence is the simultaneous movement of both eyes in opposite directions to obtain or maintain single binocular vision.[1]

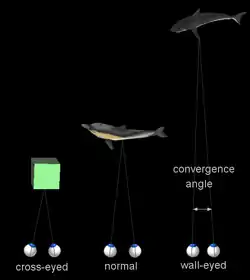

When a creature with binocular vision looks at an object, the eyes must rotate around a vertical axis so that the projection of the image is in the centre of the retina in both eyes. To look at an object closer by, the eyes rotate towards each other (convergence), while for an object farther away they rotate away from each other (divergence). Exaggerated convergence is called cross eyed viewing (focusing on the nose for example). When looking into the distance, the eyes diverge until parallel, effectively fixating the same point at infinity (or very far away).

Vergence movements are closely connected to accommodation of the eye. Under normal visual conditions, looking at an object at a different distance will automatically cause changes in both vergence and accommodation, sometimes known as the accommodation-convergence reflex. When under non-typical visual conditions like when looking at a stereogram, the vergence and accommodation of the eyes will not match, resulting in the viewer experiencing the vergence-accommodation conflict.

As opposed to the 500°/s velocity of saccade movements, vergence movements are far slower, around 25°/s. The extraocular muscles may have two types of fiber each with its own nerve supply, hence a dual mechanism.

Types

The following types of vergence are considered to act in superposition:

- Tonic vergence: vergence due to normal extraocular muscle tone, with no accommodation and no stimulus to binocular fusion. Tonic vergence is considered to move the eyes from an anatomical position of rest (which would be the eye's position if it were not innervated) to the physiological position of rest.[2]

- Accommodative vergence: blur-driven vergence.

- Fusional vergence (also: disparity vergence, disparity-driven vergence, or reflex vergence[2]): vergence induced by a stimulus to binocular fusion.

- Proximal vergence: vergence due to the awareness of a fixation object being near or far in the absence of disparity and of cues for accommodation. This includes also vergence that is due to a subject's intent to fixate an object in the dark.[3]

Accommodative vergence is measured as the ratio between how much convergence takes place for a given accommodation (AC/A ratio, CA/C ratio).

Proximal vergence is sometimes also called voluntary vergence, which however more generally means vergence under voluntary control and is sometimes considered a fifth type of vergence.[4] Voluntary vergence is also required for viewing autostereograms as well as for voluntary crossing of the eyes. Voluntary convergence is normally accompanied by accommodation and miosis (constriction of the pupil); often however, with extended practice, individuals can learn to dissociate accommodation and vergence.[5]

Vergence is also denoted according to its direction: horizontal vergence, vertical vergence, and torsional vergence (cyclovergence). Horizontal vergence is further distinguished into convergence (also: positive vergence) or divergence (also: negative vergence). Vergence eye movements result from the activity of six extraocular muscles. These are innerved from three cranial nerves: the abducens nerve, the trochlear nerve and the oculomotor nerve. Horizontal vergence involves mainly the medial and lateral rectus.

Convergence

In ophthalmology, convergence is the simultaneous inward movement of both eyes toward each other, usually in an effort to maintain single binocular vision when viewing an object.[6] This is the only eye movement that is not conjugate, but instead adducts the eye.[7] Convergence is one of three processes an eye does to properly focus an image on the retina. In each eye, the visual axis will point towards the object of interest in order to focus it on the fovea.[8] This action is mediated by the medial rectus muscle, which is innervated by Cranial nerve III. It is a type of vergence eye movement and is done by extrinsic muscles. Diplopia, commonly referred to as double vision, can result if one of the eye's extrinsic muscles are weaker than the other. This results because the object being seen gets projected to different parts of the eye's retina, causing the brain to see two images.

Convergence insufficiency is a common problem with the eyes, and is the main culprit behind eyestrain, blurred vision, and headaches.[9] This problem is most commonly found in children.

Near point of convergence (NPC) is measured by bringing an object to the nose and observing when the patient sees double, or one eye deviates out. Normal NPC values are up to 10 cm. Any NPC value greater than 10 cm is remote, and usually due to high exophoria at near.

Divergence

In ophthalmology, divergence is the simultaneous outward movement of both eyes away from each other, usually in an effort to maintain single binocular vision when viewing an object. It is a type of vergence eye movement. A divergence of the eyes in the vertical direction is physiologically seen during a head tilt, due to vestibular signaling, and when viewing a rotating visual image.[10] While the visual system is generally poor at adjusting to the acceleration of visual motion, this vertical divergence has proven more adaptable, possibly being caused by a visually induced activation of the vestibular nuclei, which usually convey information from the accelerometers of the inner ear.[11]

Vergence dysfunction

A number of vergence dysfunctions exist:[12][13]

- Basic exophoria

- Convergence insufficiency

- Convergence micropsia

- Divergence excess

- Basic esophoria

- Convergence excess

- Divergence insufficiency

- Fusional vergence dysfunction (reduced positive and negative fusional vergence, with normal or near-normal phoria)

- Heterophoria

Vergence control, and over-convergence associated with the extra accommodation required to overcome a hyperopic refractive error, play a role in the onset of accommodative esotropia. The classical explanation for the onset of accommodative esotropia is a compensation of far-sightedness by means of excessive accommodative convergence. It is an active area of research to understand the reasons why many infants with hyperopia develop accommodative esotropia whereas others do not, and which is the exact influence of the vergence system in this context.[14]

See also

References

- Cassin, B (1990). Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Solomon S. Gainesville, Fl: Triad Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-937404-68-3.

- George K. Hung; Kenneth J. Ciuffreda (31 January 2002). Models of the Visual System. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-306-46715-8.

- Ian P. Howard (January 1995). Binocular Vision and Stereopsis. Oxford University Press. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-19-508476-4.

- Penelope S. Suter; Lisa H. Harvey (2 February 2011). Vision Rehabilitation: Multidisciplinary Care of the Patient Following Brain Injury. CRC Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-4398-3656-9.

- C. Keith Barnes (May 1949). "Voluntary dissociation of the accommodation and the convergence faculty: Two observations". Arch. Ophthalmol. 41 (5): 599–606. doi:10.1001/archopht.1949.00900040615008.

- Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company, 1990.

- Reeves & Swenson, "Disorders of the Nervous System" Dartmouth Medical School http://www.dartmouth.edu/~dons/part_1/chapter_4.html Archived 2020-08-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Saladin, "Anatomy and Physiology The Unity of Form and Function, 6th Ed. McGraw-Hill"

- "FOR PARENTS, STUDENTS, FARSIGHTED CHILDREN: What is Convergence Insufficiency Disorder? Eyestrain with reading or close work, blurred vision, blurry eyesight, exophoria, double vision, problems with near vision or seeing up close, headaches, exophoric". Convergenceinsufficiency.org. Retrieved 2012-03-05.

- Wibble, T; Pansell, T (2019). "Vestibular Eye Movements Are Heavily Impacted by Visual Motion and Are Sensitive to Changes in Visual Intensities". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 60 (4). doi:10.1167/iovs.19-26706.

- Wibble, T; Engström, J; Pansell, T (2020). "Visual and Vestibular Integration Express Summative Eye Movement Responses and Reveal Higher Visual Acceleration Sensitivity than Previously Described". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 61 (5). doi:10.1167/iovs.61.5.4. PMC 7405760.

- "Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline: Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction" (PDF). American Optometric Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Duane A. "A new classification of the motor anomalies of the eyes based upon physiological principles, together with their symptoms, diagnosis and treatment." Ann Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 5:969.1869;6:94 and 247.1867.

- Babinsky E, Candy TR (2013). "Why do only some hyperopes become strabismic?". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science (Review). 54 (7): 4941–55. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-10670. PMC 3723374. PMID 23883788.