Verseghya thysanophora

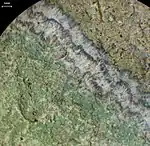

Verseghya thysanophora, commonly known as the mapledust lichen, is a species of mostly corticolous (bark-dwelling), leprose lichen in the family Pertusariaceae.[2] This common species is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere. The thallus of the lichen is a thin patchy layer of granular soredia, pale green to yellowish green in colour. The main characteristics of the lichen include the presence of lichen products known as thysanophora unknowns, and the conspicuous white, fibrous prothallus that encircles the thallus.

| Verseghya thysanophora | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Lecanoromycetes |

| Order: | Pertusariales |

| Family: | Pertusariaceae |

| Genus: | Verseghya |

| Species: | V. thysanophora |

| Binomial name | |

| Verseghya thysanophora (R.C.Harris) S.Y.Kondr., Lőkös, Farkas & Hur (2019) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Taxonomy

The species was first formally described as Lecanora thysanophora by lichenologist Richard C. Harris in 2000. The type specimen was collected in 1996 by William Buck on the trail to the Gulf Unique Area in Mooers, New York; there, in conifer-maple woodland, it was found growing on a maple tree.[3] The taxon was transferred to the newly circumscribed genus Verseghya in 2019 by Sergey Kondratyuk and colleagues.[4]

In North America, the common name "mapledust lichen" is sometimes used to refer to this species.[5]

Description

Verseghya thysanophora is pale yellow to greenish in colour, sometimes with blue or grey tones in shaded areas. It has a thin, leprose and sometimes patchy appearance. A visible, white and fibrous prothallus is often present with hyphae arranged in distinct radiating strands. Soralia can be either discrete or form a continuous crust. The lichen has a green algal photobiont (trebouxioid) that is 8–12 μm in diameter.[3]

Apothecia, which are the reproductive structures of lichens, are rarely seen but can sometimes be abundant. They are pale yellowish brown to greyish brown in colour, and the margins are raised and distinctly yellow or whitish, which can contrast with the colour of the thallus. Asci contain eight spores and measure up to 90 by 20 μm; they are of the Lecanora-type, with a distinct tholus but lacking an ocular chamber. The ascospores lack any septa, and are hyaline and ellipsoid, with dimensions of 11–14 by 6–9 μm.[3]

Verseghya thysanophora contains a set of unidentified terpenoids that have been named "thysanophora unknowns." These substances can be detected using thin-layer chromatography, and they appear ice blue under long wavelength UV light after charring. The lichen also contains atranorin, usnic acid, and zeorin; porphyrilic acid is present in about a quarter of collected specimens.[3]

Similar species

Verseghya thysanophora is often confused with Lepraria, but this genus lack the white fimbriate margin and patchiness of parts of the thallus found in Verseghya thysanophora. Lepraria species are usually restricted to tree bases, while Verseghya thysanophora is commonly found higher up on the trunk and can form large patches. Lecanora expallens is similar in colour, but has a more coastal distribution, contains different chemical compounds, and has a bluish-grey prothallus. Sterile specimens of Verseghya thysanophora are morphologically similar to the European lichen Haematomma ochroleucum, but can be distinguished by the presence of thysanophora unknowns in Verseghya thysanophora, which are not found in Haematomma ochroleucum.[3] In a 2005 study, it was found that all Lithuanian specimens identified previously as Haematomma ochroleucum were in fact Verseghya thysanophora;[6] a similar situation was reported with Polish herbarium specimens.[7]

Habitat and distribution

Verseghya thysanophora is commonly found growing on the trunks of deciduous trees, especially Acer saccharum and Thuja occidentalis, as well as occasionally on shaded siliceous rocks. This lichen is typically found in mature maple forests, and is most often fertile on trees that are located near streams. It is widespread throughout the East Temperate region of North America.[3] In Europe, it has been recorded from Austria,[8] Belarus,[9] Bulgaria,[10] Germany,[11] Poland,[7] and Slovenia.[12] In 2011, it was reported from Jinzhai County, China,[13] and in 2015, in South America, from Santana do Livramento, Brazil.[14]

References

- "Synonymy. Current Name: Verseghya thysanophora (R.C. Harris) S.Y. Kondr., Lőkös, Farkas & Hur, in Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur & Farkas, Acta bot. hung. 61(1-2): 158 (2019)". Species Fungorum. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "Verseghya thysanophora (R.C. Harris) S.Y. Kondr., Lőkös, Farkas & Hur". Catalogue of Life. Species 2000: Leiden, the Netherlands. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- Harris, Richard C.; Brodo, Irwin M.; Tønsberg, Tor (2000). "Lecanora thysanophora, a common leprose lichen in eastern North America". The Bryologist. 103 (4): 790–793. doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2000)103[0790:ltacll]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 3244346. S2CID 85751323.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Lőkös, L.; Jang, S.-H.; Hur, J.-S.; Farkas, E. (2019). "Phylogeny and taxonomy of Polyozosia, Sedelnikovaea and Verseghya of the Lecanoraceae (Lecanorales, lichen-forming Ascomycota)" (PDF). Acta Botanica Hungarica. 61 (1–2): 137–184. doi:10.1556/034.61.2019.1-2.9. S2CID 133258087.

- Brodo, Irwin M.; Sharnoff, Sylvia Duran; Sharnoff, Stephen (2001). Lichens of North America. Yale University Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-300-08249-4.

- Kukwa, Martin; Motiejūnaitų, Jurga (2005). "Notes on Haematomma ochroleucum and lecanora thysanophora lichens in Lithuania". Botanica Lithuanica (1392-1665). 1 (4): 247–249.

- Kowalewska, A.; Kukwa, M. (2003). "Additions to the Polish lichen flora". Graphis Scripta. 14: 11–17.

- Tønsberg, T.; Türk, R.; Hofmann, P. (2001). "Notes on the lichen flora of Tyrol (Austria)". Nova Hedwigia. 72 (3–4): 487–497. doi:10.1127/nova.hedwigia/72/2001/487.

- Golubkov, Vladimir V.; Kukwa, Martin (2006). "A contribution to the lichen biota of Belarus" (PDF). Acta Mycologica. 41 (1): 155–164. doi:10.5586/am.2006.019. S2CID 83907133.

- Otte, Volker (2005). "Noteworthy lichen records for Bulgaria". Abhandlungen und Berichte des Naturkundemuseums Görlitz. 77 (1): 77–86.

- Printzen, C.; Halda, J.; Palice, Z.; Tønsberg, T. (2002). "New and interesting lichen records from old-growth forest stands in the German National Park Bayerischer Wald". Nova Hedwigia. 71 (1–2): 25–49. doi:10.1127/0029-5035/2002/0074-0025.

- Bilovitz, Peter O.; Batič, Franc; Mayrhofer, Helmut (2011). "Epiphytic lichen mycota of the virgin forest reserve Rajhenavski Rog (Slovenia)". Herzogia. 24 (2): 315–324. doi:10.13158/heia.24.2.2011.315. PMC 3430848. PMID 22942459.

- Han, Liu-Fu; Guo, Shou-Yu; Zhang, Hao (2011). "Three corticolous species of Lecanora (Lecanoraceae) new to China" (PDF). Mycotaxon. 116 (1): 21–25. doi:10.5248/116.21.

- Käffer, Márcia I.; Koch, Natália M.; Aptroot, André; Martins, Suzana M. de A. (2014). "New records of corticolous lichens for South America and Brazil". Plant Ecology and Evolution. 148 (1): 111–118. doi:10.5091/plecevo.2015.961.