Catholic Church in Vietnam

The Catholic Church in Vietnam is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of bishops in Vietnam who are in communion with the pope in Rome. Vietnam has the fifth largest Catholic population in Asia, after the Philippines, India, China and Indonesia. There are about 7 million Catholics in Vietnam, representing 7.0% of the total population.[1] There are 27 dioceses (including three archdioceses) with 2,228 parishes and 2,668 priests.[2] The main liturgical rites employed in Vietnam are those of the Latin Church.

Catholic Church in Vietnam | |

|---|---|

| Giáo hội Công giáo Việt Nam | |

| Classification | Catholic |

| Orientation | Latin |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governance | Catholic Bishops' Conference of Vietnam |

| Pope | Francis |

| CBCV President | Joseph Nguyễn Năng |

| Apostolic Delegation | Marek Zalewski |

| Associations | Committee for Solidarity of Vietnamese Catholics (in Vietnamese Fatherland Front), state-controlled |

| Language | Vietnamese, Latin |

| Headquarters | Ho Chi Minh City |

| Origin | 1533 or 1615 |

| Members | 7 million (2020) |

| Official website | Catholic Bishops' Conference of Vietnam |

History

Early periods

The first Catholic missionaries visited Vietnam from Portugal and Spain in the 16th century. The earliest missions did not bring impressive results. Only after the arrival of Jesuits in the first decades of the 17th century did Christianity begin to establish its positions within the local populations in both domains of Đàng Ngoài (Tonkin) and Đàng Trong (Cochinchina).[3] These missionaries were mainly Italians, Portuguese, and Japanese. Two priests, Francesco Buzomi and Diogo Carvalho, established the first Catholic community in Hội An in 1615. Between 1627 and 1630, Avignonese Alexandre de Rhodes and Portuguese Pero Marques converted more than 6,000 people in Tonkin.[4]

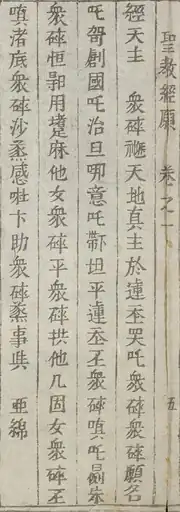

In the 17th century, Jesuit missionaries including Francisco de Pina, Gaspar do Amaral, Antonio Barbosa, and de Rhodes developed an alphabet for the Vietnamese language, using the Latin script with added diacritic marks.[5] This writing system continues to be used today, and is called chữ Quốc ngữ (literally "national language script"). Meanwhile, the traditional chữ Nôm, in which Girolamo Maiorica was an expert, was the main script conveying Catholic faith to Vietnamese until the late 19th century.[6]

Since the late 17th century, French missionaries of the Foreign Missions Society and Spanish missionaries of the Dominican Order were gradually taking the role of evangelization in Vietnam. Other missionaries active in pre-modern Vietnam were Franciscans (in Cochinchina), Italian Dominicans & Discalced Augustinians (in Eastern Tonkin), and those sent by the Propaganda Fide.

Missionaries and the Nguyễn

The French missionary priest and Bishop of Adraa Pigneau de Behaine played a key role in Vietnamese history towards the end of the 18th century. He had come to southern Vietnam to evangelize. In 1777, the Tây Sơn brothers killed the ruling Nguyễn lords. Nguyễn Ánh was the most senior member of the family to have survived, and he fled into the Mekong Delta region in the far south, where he met Pigneau.[7] Pigneau became Nguyễn Ánh's confidant.[8][9] Pigneau reportedly hoped that by playing a substantial role in helping Ánh attain victory, he would be in position to gain important concessions for the Catholic Church in Vietnam and helping its expansion throughout Southeast Asia. From then on he became a politician and military strategist.[10]

At one stage during the civil war, the Nguyễn were in trouble, so Pigneau was dispatched to seek French aid. He was able to recruit a band of French volunteers.[11] Pigneau and other missionaries acted as business agents for Nguyễn Ánh, purchasing munitions and other military supplies.[12] Pigneau also served as a military advisor and de facto foreign minister until his death in 1799.[13][14] From 1794, Pigneau took part in all campaigns. He organized the defense of Diên Khánh when it was besieged by a numerically vastly superior Tây Sơn army in 1794.[15] Upon Pigneau's death,[16] Gia Long's funeral oration described the Frenchman as "the most illustrious foreigner ever to appear at the court of Cochinchina".[17][18]

By 1802, when Nguyễn Ánh conquered all of Vietnam and declared himself Emperor Gia Long, the Catholic Church in Vietnam had three dioceses as follows:

- Diocese of Eastern Tonkin: 140,000 members, 41 Vietnamese priests, 4 missionary priests and 1 bishop.

- Diocese of Western Tonkin: 120,000 members, 65 Vietnamese priests, 46 missionary priests and 1 bishop.

- Diocese of Central and Southern Cochinchina: 60,000 members, 15 Vietnamese priests, 5 missionary priests and 1 bishop.[19]

Gia Long tolerated the Catholic faith of his French allies and permitted unimpeded missionary activities out of respect to his benefactors.[20] The missionary activities were dominated by the Spanish in Tonkin and the French in the central and southern regions.[21] At the time of his death, there were six European bishops in Vietnam.[21] The population of Christians was estimated at 300,000 in Tonkin and 60,000 in Cochinchina.[22]

Later Nguyễn dynasty

The peaceful coexistence of Catholicism alongside the classical Confucian system of Vietnam was not to last. Gia Long himself was Confucian in outlook. As Crown Prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh had already died, it was assumed that Cảnh's son would succeed Gia Long as emperor, but, in 1816, Nguyễn Phúc Đảm, the son of Gia Long's second wife, was appointed instead.[23] Gia Long chose him for his strong character and his deeply conservative aversion to Westerners, whereas Cảnh's lineage had converted to Catholicism and were reluctant to maintain their Confucian traditions such as ancestor worship.[24]

Lê Văn Duyệt, the Vietnamese general who helped Nguyễn Ánh—the future Emperor Gia Long—put down the Tây Sơn rebellion, unify Vietnam and establish the Nguyễn dynasty, and many of the high-ranking mandarins opposed Gia Long's succession plan.[25] Duyệt and many of his southern associates tended to be favourable to Christianity, and supported the installation of Nguyễn Cảnh's descendants on the throne. As a result, Duyệt was held in high regard by the Catholic community.[26] According to the historian Mark McLeod, Duyệt was more concerned with military rather than social needs, and was thus more interested in maintaining strong relations with Europeans so that he could acquire weapons from them, rather than worrying about the social implications of westernization.[26] Gia Long was aware that Catholic clergy were opposed to the installation of Minh Mạng because they favored a Catholic monarch (Cảnh's son) who would grant them favors.[26]

Minh Mạng began to place restrictions on Catholicism.[27] He enacted "edicts of interdiction of the Catholic religion" and condemned Christianity as a "heterodox doctrine". He saw the Catholics as a possible source of division,[27] especially as the missionaries were arriving in Vietnam in ever-increasing numbers.[28] Duyệt protected Vietnamese Catholic converts and westerners from Minh Mạng's policies by disobeying the emperor's orders.[29]

Minh Mạng issued an imperial edict, that ordered missionaries to leave their areas and move to the imperial city, ostensibly because the palace needed translators, but in order to stop the Catholics from evangelizing.[30] Whereas the government officials in central and northern Vietnam complied, Duyệt disobeyed the order and Minh Mạng was forced to bide his time.[30] The emperor began to slowly wind back the military powers of Duyệt, and increased this after his death.[31] Minh Mạng ordered the posthumous humiliation of Duyệt, which resulted in the desecration of his tomb, the execution of sixteen relatives, and the arrests of his colleagues.[32] Duyệt's son, Lê Văn Khôi, along with the southerners who had seen their and Duyệt's power curtailed, revolted against Minh Mạng.

Khôi declared himself in favour of the restoration of the line of Prince Cảnh.[33] This choice was designed to obtain the support of Catholic missionaries and Vietnamese Catholics, who had been supporting the Catholic line of Prince Cảnh. Lê Văn Khôi further promised to protect Catholicism.[33] In 1833, the rebels took over southern Vietnam,[33][34] with Catholics playing a large role.[35] 2,000 Vietnamese Catholic troops fought under the command of Father Nguyễn Văn Tâm.[36]

The rebellion was suppressed after three years of fighting. The French missionary Father Joseph Marchand, of the Paris Foreign Missions Society was captured in the siege, and had been supporting Khôi, and asked for the help of the Siamese army, through communications to his counterpart in Siam, Father Jean-Louis Taberd. This showed the strong Catholic involvement in the revolt and Father Marchand was executed.[34]

The failure of the revolt had a disastrous effect on the Christians of Vietnam.[35] New restrictions against Christians followed, and demands were made to find and execute remaining missionaries.[36] Anti-Catholic edicts to this effect were issued by Minh Mạng in 1836 and 1838. In 1836–37 six missionaries were executed: Ignacio Delgado, Dominico Henares, José Fernández, François Jaccard, Jean-Charles Cornay, and Bishop Pierre Borie.[37][38] The villages of Christians were destroyed and their possessions confiscated. Families were broken apart. Christians were branded on the forehead with tà đạo, “false religion.” It is believed that between 130,000 and 300,000 Christians died in the various persecutions. The 117 proclaimed saints represent the many unknown martyrs.

Catholicism in South Vietnam (1954–1975)

From 1954 to 1975, Vietnam was split into North and South Vietnam. During a 300-day period where the border between the two sides was temporarily open, many North Vietnamese Catholics fled southward out of fear that they would be persecuted by the Viet Minh.

In a country where Buddhists were the majority,[39][40][41][42][43][44][45] President Ngô Đình Diệm's policies generated claims of religious bias even though he sponsored and supported many Buddhist organizations, and Buddhism flourished under his regime.[46] As a member of the Catholic minority, he pursued policies which antagonized the Buddhist majority. The government was biased towards Catholics in public service and military promotions, and the allocation of land, business favors and tax concessions.[47] Diệm once told a high-ranking officer, forgetting the man was from a Buddhist background, "Put your Catholic officers in sensitive places. They can be trusted."[48] Many officers in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam converted to Catholicism to better their prospects.[48] The distribution of firearms to village self-defense militias intended to repel Việt Cộng guerrillas saw weapons only given to Catholics.[49] Some Catholic priests ran their own private armies,[50] and in some areas forced conversions, looting, shelling and demolition of pagodas occurred.[51]

Some villages converted en masse in order to receive aid or avoid being forcibly resettled by Diệm's regime.[52] The Catholic Church was the largest landowner in the country, and its holdings were exempt from reform and given extra property acquisition rights, while restrictions against Buddhism remained in force.[53][54] Catholics were also de facto exempt from the corvée labor that the government obliged all citizens to perform; U.S. aid was disproportionately distributed to Catholic majority villages. In 1959, Diem dedicated his country to the Virgin Mary.[55]

The white and gold "Vatican flag" was regularly flown at all major public events in South Vietnam.[56] The newly constructed Huế and Đà Lạt universities were placed under Catholic authority to foster a Catholic-influenced academic environment.[57]

In May 1963, in the central city of Huế, where Diệm's elder brother Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục was archbishop, Buddhists were prohibited from displaying the Buddhist flag during the sacred Buddhist Vesak celebrations.[58] A few days earlier, Catholics were encouraged to fly religious—that is, papal—flags at the celebration in honour of Thục's anniversary as bishop.[59] Both actions technically violated a rarely enforced law which prohibited the flying of any flag other than the national one, but only the Buddhist flags were prohibited in practice.[59] This prompted a protest against the government, which was violently suppressed by Diệm's forces, resulting in the killing of nine civilians. This in turn led to a mass campaign against Diệm's government during what became known as the Buddhist crisis. Diệm was later deposed and assassinated on 2 November 1963.[60][61] Recent scholarships reveal significant understandings about Diệm's own independent agenda and political philosophy.[62] The Personalist Revolution under his regime promoted religious freedom and diversity to oppose communism's atheism. However, this policy itself ultimately enabled religious activists to threaten the state that supported their religious liberty.[63]

Present time

The first Vietnamese bishop, Jean-Baptiste Nguyễn Bá Tòng, was consecrated in 1933 at St. Peter's Basilica by Pope Pius XI.[19] The Catholic Bishops' Conference of Vietnam was founded in 1980. In 1976, the Holy See made Archbishop Joseph-Marie Trịnh Như Khuê the first Vietnamese cardinal. Joseph-Marie Cardinal Trịnh Văn Căn in 1979, and Paul-Joseph Cardinal Phạm Đình Tụng in 1994, were his successors. The well known Vietnamese Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyễn Văn Thuận, who was imprisoned by the Communist regime from 1975 to 1988 and spent nine years in solitary confinement, was nominated secretary of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, and made its president in 1998. On 21 February 2001, he was elevated to the College of Cardinals by Pope John Paul II.[19] Vietnamese Catholics who died for their faith from 1533 to the present day were canonized in 1988 by John Paul II as "Vietnamese Martyrs". On 26 March 1997, the beatification process for the Redemptorist brother Marcel Nguyễn Tân Văn was opened by Cardinal Nguyễn Văn Thuận in the diocese of Belley-Ars, France.

There have been meetings between leaders of Vietnam and the Vatican, including a visit by Vietnam's Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng to the Vatican to meet Pope Benedict XVI on 25 January 2007. Official Vatican delegations have been traveling to Vietnam almost every year since 1990 for meetings with its government authorities and to visit Catholic dioceses. In March 2007, a Vatican delegation visited Vietnam and met with local officials.[64] In October 2014, Pope Francis met with Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng in Rome. The sides continued discussions about the possibility of establishing normal diplomatic relations, but have not provided a specific schedule for the exchange of ambassadors.[65] The Pope would again meet Vietnamese leader Trần Đại Quang and his associates in Vatican in 2016.[66]

Vietnam remains as the only Asian communist country to have an unofficial representative of the Vatican in the country and has held official to unofficial meetings with the Vatican's representatives both in Vietnam and the Holy See—which does not exist in China, North Korea and Laos—due to long and historical relations between Vietnam and the Catholic Church dating to before the period of French colonization in Southeast Asia. These relations have improved in recent years, as the Holy See announced they will have a permanent representative in Vietnam in 2018.[67][68]

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church by country |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Restrictions on Catholic life in Vietnam and the government's desired involvement in the nomination of bishops remain obstacles in bilateral dialogues. In March 2007, Thaddeus Nguyễn Văn Lý (b. 1946), a dissident Catholic priest, was sentenced by Vietnamese court in Huế to eight years in prison on grounds of "anti-government activities". Nguyen, who had already spent 14 of the past 24 years in prison, was accused of being a founder of a pro-democracy movement Bloc 8406 and a member of the Progression Party of Vietnam.[69]

On 16 September 2007, the fifth anniversary of the Cardinal Nguyễn Văn Thuận's death, the Catholic Church began the beatification process for him.[70] Benedict XVI expressed "profound joy" at the news of the official opening of the beatification cause.[71] Vietnamese Catholics reacted positively to the news of the beatification. In December 2007, thousands of Vietnamese Catholics marched in procession to the former apostolic nunciature in Hanoi and prayed there twice aiming to return the property to the local church.[72] The building was located at a historic Buddhist site until it was confiscated by the French authorities and given to Catholics, before the communist North Vietnamese government confiscated it from the Catholic Church in 1959.[73] This was the first mass civil action by Vietnamese Catholics since the 1970s. Later the protests were supported by Catholics in Hồ Chí Minh City and Hà Đông, who made the same demands for their respective territories.[74] In February 2008, the governments promised to return the building to the Catholic Church.[75] However, in September 2008, the authorities changed their position and decided to demolish the building to create a public park.[76]

Dioceses

There are 27 dioceses, including three archdioceses, in a total of three ecclesiastical provinces. The archdioceses are:[77]

See also

- Religion in Vietnam

- Christianity in Vietnam

- Vietnamese Martyrs

- Our Lady of La Vang

- Đọc kinh (Vietnamese cantillation)

- Ngắm Mùa Chay (Vietnamese Lenten meditation)

- Holy See-Vietnam relations

Citations

- Antôn Nguyễn Ngọc Sơn (2020). "Giáo trình lớp Hội nhập Văn hoá Văn hoá Công Giáo Việt Nam".

- Archived 18 December 2016 at the Wayback MachineBased on individual diocesan statistics variously reported in 2012, 2013 and 2014.

- Tran (2018).

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Indochina Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Trần, Quốc Anh; Phạm, Thị Kiều Ly (October 2019). Từ Nước Mặn đến Roma: Những đóng góp của các giáo sĩ Dòng Tên trong quá trình La tinh hoá tiếng Việt ở thế kỷ 17. Conference 400 năm hình thành và phát triển chữ Quốc ngữ trong lịch sử loan báo Tin Mừng tại Việt Nam. Hochiminh City: Committee on Culture, Catholic Bishops' Conference of Vietnam.

- Ostrowski (2010), pp. 23, 38.

- McLeod, p. 7.

- Hall, p. 423.

- Buttinger, p. 234.

- McLeod, p. 9.

- Buttinger, pp. 237–40.

- McLeod, p. 10.

- Cady, p. 284.

- Hall, p. 431.

- Mantienne, p.135

- Karnow, p. 77.

- Buttinger, p. 267.

- Karnow, p. 78.

- "Catholic Church in Vietnam with 470 years of Evangelization". Rev. John Trần Công Nghị, Religious Education Congress in Anaheim. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- Buttinger, pp. 241, 311.

- Cady, p. 408.

- Cady, p. 409.

- Buttinger, p. 268.

- Buttinger, p. 269.

- Choi, pp. 56–57

- McLeod, p. 24.

- McLeod, p. 26.

- McLeod, p. 27.

- Choi, pp. 60–61

- McLeod, p. 28.

- McLeod, pp. 28–29.

- McLeod, p. 29.

- McLeod, p. 30

- Chapuis, p. 192

- Wook, p. 95

- McLeod, p. 31

- McLeod, p. 32

- The Cambridge History of Christianity, p. 517 Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- The 1966 Buddhist Crisis in South Vietnam Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine HistoryNet

- Gettleman, pp. 275–76, 366.

- Moyar, pp. 215–216.

- "South Viet Nam: The Religious Crisis". Time. 14 June 1963. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Tucker, pp. 49, 291–93.

- Maclear, p. 63.

- SNIE 53-2-63, "The Situation in South Vietnam, 10 July 1963 Archived 1 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Lữ Giang (2009). Những bí ẩn đằng sau các cuộc thánh chiến tại Việt Nam. pp. 47–50.

- Tucker, p. 291.

- Gettleman, pp. 280–82.

- "South Vietnam: Whose funeral pyre?". New Republic. 29 June 1963. p. 9.

- Warner, p. 210.

- Fall, Bernard (1963), The Two Viet-Nams, p. 199.

- Buttinger, p. 993.

- Karnow, p. 294.

- Buttinger p. 933.

- Jacobs p. 91.

- "Diệm's other crusade". New Republic. 22 June 1963. pp. 5–6.

- Halberstam, David (17 June 1963). "Diệm and the Buddhists". The New York Times.

- Topmiller, p. 2.

- Jarvis, p. 59.

- Karnow, p. 295.

- Moyar, pp. 212–13.

- Taylor, K. W. (2020). "Taylor on Nguyen, 'The Unimagined Community: Imperialism and Culture in South Vietnam'". H-Net Reviews.

- Nguyen, Phi-Vân (2018). "A Secular State for a Religious Nation: The Republic of Vietnam and Religious Nationalism, 1946–1963". The Journal of Asian Studies. 77 (3): 741–771. doi:10.1017/S0021911818000505.

The spiritual dimension of the Republic's Personalist Revolution did not involve state interference in all religious activities. Instead, it promoted religious freedom and diversity, provided that the spiritual values they propagated opposed communism's atheism. ... The Republic pledged to defend freedom of religion—at least initially—and promoted religious diversity. Ironically, it was precisely because the state could guarantee neither religious equality nor absolute noninterference in religious affairs that religious groups started to challenge its authority.

- "Vatican: Vietnam working on full diplomatic relations with Holy See". Catholic News Service. 12 March 2007. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- "Vatican and Vietnam edge closer to restoring diplomatic ties". AFP. 19 October 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- "Pope Francis welcomes Vietnamese leader's visit to Vatican".

- "Holy See to have permanent representative in Vietnam | ROME REPORTS".

- "Vatican, Vietnam move closer to full diplomatic relations". 21 December 2018.

- Asia News, March 2007 Archived 27 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Late Vietnamese cardinal put on road to sainthood". Reuters. 17 September 2007.

- UCANews at Catholic.org Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- UCA News Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Pham, Nga (2008). "Holy row over land in Vietnam". BBC News.

- "Vietnamese Catholics broaden their protest demanding justice" Archived 24 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Asianews, 15 January 2008

- "Archbishop of Hanoi confirms restitution of nunciature, thanks pope" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "In Hanoi, stance of repression against Catholics seems to have won" Archived 5 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Asianews], September 2008

- "Catholic Dioceses in Vietnam". GCatholic.org.

Bibliography

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Praeger Publishers

- Cady, John F. (1964), Southeast Asia: Its Historical Development, McGraw Hill

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995), A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-29622-2

- Choi Byung, Wook (2004), Southern Vietnam under the reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): central policies and local response, SEAP Publications, ISBN 0-87727-138-0

- Gettleman, Marvin E. (1966), Vietnam: History, documents and opinions on a major world crisis, New York: Penguin Books

- Hammer, Ellen J. (1987), A Death in November, Boston: E. P. Dutton, ISBN 0-525-24210-4

- Hall, D.G. E. (1981), A History of South-east Asia, Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-24163-0

- Jacobs, Seth (2006), Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-4447-8

- Jones, Howard (2003), Death of a Generation, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-505286-2

- Karnow, Stanley (1997), Vietnam: A history, New York: Penguin Books, ISBN 0-670-84218-4

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991), The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention, 1862–1874, Praeger, ISBN 0-275-93562-0

- McLeod, Mark W. (1992). "Nationalism and Religion in Vietnam: Phan Boi Chau and the Catholic Question". The International History Review. 14 (4): 661–680. doi:10.1080/07075332.1992.9640628.

- Shaw, Geoffrey (2015). The Lost Mandate of Heaven: The American Betrayal of Ngo Dinh Diem, President of Vietnam. Ignatius Press.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2000), Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-57607-040-9

- Warner, Denis (1963), The Last Confucian, New York: Macmillan

- Cao, Huy Thuan (1969). Christianisme et colonialisme au Vietnam (1857–1914) (PhD). Faculté de droit et des sciences économiques de Paris.

- Lê, Nicole-Dominique (1975). Les Missions-Étrangères et la pénétration française au Viêt-Nam. Mouton. ISBN 2719306118.

- Tuck, Patrick J. N. (1987). French Catholic Missionaries and the Politics of Imperialism in Vietnam, 1857–1914: A Documentary Survey. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0853231362.

- Miller, Edward (2013). Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the Fate of South Vietnam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674072985.

- Goscha, Christopher (2016). Vietnam: A New History. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465094363.

- Tran, Nu-Anh (2022). Disunion: Anticommunist Nationalism and the Making of the Republic of Vietnam. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 9780824887865.

- Nguyen-Marshall, Van (2023). Between War and the State: Civil Society in South Vietnam, 1954–1975. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501770579.

Monographs

- Ramsay, Jacob (2008). Mandarins and Martyrs: The Church and the Nguyen Dynasty in Early Nineteenth-Century Vietnam. Stanford University Press. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804756518.001.0001. ISBN 9780804756518.

- Keith, Charles (2012). Catholic Vietnam: A Church from Empire to Nation. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520272477.001.0001. ISBN 9780520272477.

- Mantienne, Frédéric (2012). Pierre Pigneaux: Évêque d'Adran et mandarin de Cochinchine (1741–1799). Les Indes savantes. ISBN 9782846542883.

- Dutton, George E. (2016). A Vietnamese Moses: Philiphê Bỉnh and the Geographies of Early Modern Catholicism. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/luminos.22. ISBN 9780520293434.

- Tran, Anh Q. (2017). Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors: An Interreligious Encounter in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190677602.001.0001. ISBN 9780190677602.

- Tran, Anh Q. (2018). "The Historiography of the Jesuits in Vietnam: 1615–1773 and 1957–2007". Jesuit Historiography Online. Brill. doi:10.1163/2468-7723_jho_COM_210470.

Doctoral theses:

- Trân, Thi Liên (1997). Les catholiques vietnamiens pendant la Guerre d'indépendance, 1945–1954: entre la reconquête coloniale et la résistance communiste (PhD). Institut d'études politiques de Paris.

- Forest, Alain (1997). Les missionnaires français au Tonkin et au Siam (XVIIe–XVIIIe siècles): analyse comparée d'un relatif succès et d'un total échec (PhD). Université Paris VII-Diderot.

- Massot-Marin, Catherine (1998). Le rôle de missionnaires français en Cochinchine aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: fidélité à Rome et volonté d'indépendance (PhD). Université Paris IV-Sorbonne.

- Ostrowski, Brian Eugene (2006). The Nôm Works of Geronimo Maiorica, S.J. (1589–1656) and Their Christology (PhD). Cornell University.

- Ngo, Lan A. (2016). Nguyễn–Catholic History (1770s–1890s) and the Gestation of Vietnamese Catholic National Identity (PhD). Georgetown University.

Book chapters

- Alberts, Tara (2013). "Priests of a Foreign God: Catholic Religious Leadership and Sacral Authority in Seventeenth-Century Tonkin and Cochinchina". In Alberts, Tara; Irving, D. R. M. (eds.). Intercultural Exchange in Southeast Asia: History and Society in the Early Modern World. I.B. Tauris. pp. 84–117. ISBN 9780857722836.

- Alberts, Tara (2018). "Missions in Vietnam". In Hsia, Ronnie Po-chia (ed.). A Companion to the Early Modern Catholic Global Missions. Brill. pp. 269–302. ISBN 9789004355286.

- Cooke, Nola (2013). "Early Christian Conversion in Seventeenth-Century Cochinchina". In Young, Richard Fox; Seitz, Jonathan A. (eds.). Asia in the Making of Christianity: Conversion, Agency, and Indigeneity, 1600s to the Present. Brill. pp. 29–52. ISBN 9789004251298.

- Daughton, James P. (2006). "Recasting Pigneau de Béhaine: Missionaries and the Politics of French Colonial History, 1894–1914". In Tran, Nhung Tuyet; Reid, Anthony (eds.). Viêt Nam: Borderless Histories. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 290–322. ISBN 9780299217747.

- Dutton, George (2006). "Christians and Christianity in the Tây Sơn Era". The Tay Son Uprising: Society and Rebellion in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 175–196. ISBN 9780824829841.

- Goscha, Christopher E. (2011). "Catholics in Vietnam and the War; Lê Hữu Từ; Vatican". Historical Dictionary of the Indochina War (1945–1954): An International and Interdisciplinary Approach. NIAS Press. pp. 90–91, 262–263, 481–482. ISBN 9788776940638. Online resource.

- Luria, Keith P. (2017a). "Narrating Women's Catholic Conversions in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam". In Ditchfield, Simon; Smith, Helen (eds.). Conversions: Gender and Religious Change in Early Modern Europe. Manchester University Press. pp. 195–215. ISBN 9780719099151.

- Makino, Motonori (2009). "The Vietnamese Written Languages and European Missionaries: From the Society of Jesus to the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris". In Shinzo, Kawamura; Veliath, Cyril (eds.). Beyond Borders: A Global Perspective of Jesuit Mission History. Sophia University Press. pp. 342–349. ISBN 9784324086100.

- Makino, Motonori (2020). "Native Priests in Christian Societies in the Northern Regions of Pre-Colonial Vietnam: The Appearance of a Glocal Elite?". In Hirosue, Masashi (ed.). A History of the Social Integration of Visitors, Migrants, and Colonizers in Southeast Asia: Role of Local Collaborators. Toyo Bunko. pp. 35–73. ISBN 9784809703034.

- Marr, David G. (2013). "Catholics: Allies or Enemies?". Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945–1946). University of California Press. pp. 428–441. ISBN 9780520274150.

- Nguyen, Phi-Vân (2023). "A Decolonization Gone Too Far? The Vietnamese Catholics' Search for Independence, 1941–1963". In Foster, Elizabeth A.; Greenberg, Udi (eds.). Decolonization and the Remaking of Christianity. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781512824964.

- Ostrowski, Brian (2010). "The Rise of Christian Nôm Literature in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Fusing European Content and Local Expression". In Wilcox, Wynn (ed.). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Cornell University Press. pp. 19–39. ISBN 9780877277828.

- Ramsay, Jacob (2007). "Miracles and Myths: Vietnam Seen through Its Catholic History". In Taylor, Philip (ed.). Modernity and Re-Enchantment: Religion in Post-Revolutionary Vietnam. ISEAS Publishing. pp. 371–398. ISBN 9789812304568.

- Stur, Heather Marie (2020). "The Catholic Opposition and Political Repression". Saigon at War: South Vietnam and the Global Sixties. Cambridge University Press. pp. 195–222. ISBN 9781316676752.

- Trân, Claire Thi Liên (2004). "Les catholiques et la République démocratique du Viêt Nam (1945–1954): une approche biographique". In Goscha, Christopher E.; de Tréglodé, Benoît (eds.). Naissance d'un État-Parti: Le Viêt Nam depuis 1945. Les Indes savantes. pp. 253–276. ISBN 9782846540643.

- Trân, Claire Thi Liên (2009). "Les catholiques vietnamiens et le mouvement moderniste: quelques éléments de réflexion sur la question de modernité fin xixe – début xxe siècle". In Gantès, Gilles de; Nguyen, Phuong Ngoc (eds.). Vietnam: Le moment moderniste. Presses universitaires de Provence. pp. 177–196. ISBN 9782821885653.

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2005). "Les Amantes de la Croix: An Early Modern Vietnamese Sisterhood". In Bousquet, Gisèle; Taylor, Nora (eds.). Le Viêt Nam au féminin. Les Indes savantes. pp. 51–66. ISBN 9782846540759.

- Wilcox, Wynn (2010). "Đặng Đức Tuấn and the Complexities of Nineteenth-Century Vietnamese Christian Identity". In Wilcox, Wynn (ed.). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Cornell University Press. pp. 71–87. ISBN 9780877277828.

Journal articles

- Alberts, Tara (2012). "Catholic Written and Oral Cultures in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam". Journal of Early Modern History. 16 (4–5): 383–402. doi:10.1163/15700658-12342325.

- Chu, Lan T. (2008). "Catholicism vs. Communism, Continued: The Catholic Church in Vietnam". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 3 (1): 151–192. doi:10.1525/vs.2008.3.1.151.

- Cooke, Nola (2004). "Early Nineteenth-Century Vietnamese Catholics and Others in the Pages of the Annales de la Propagation de la Foi". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 35 (2): 261–285. doi:10.1017/S0022463404000141. S2CID 153524504.

- Cooke, Nola (2008). "Strange Brew: Global, Regional and Local Factors behind the 1690 Prohibition of Christian Practice in Nguyễn Cochinchina". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 39 (3): 383–409. doi:10.1017/S0022463408000313. hdl:1885/27684. S2CID 153563604.

- Du, Yuqing (2022). "Reconfiguring Inculturations: Hội Đồng Tứ Giáo and Interfaith Dialogues in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 38–63. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.38. S2CID 250519251.

- Hansen, Peter (2009). "Bắc Di Cư: Catholic Refugees from the North of Vietnam, and Their Role in the Southern Republic, 1954–1959". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 4 (3): 173–211. doi:10.1525/vs.2009.4.3.173.

- Hoang, Tuan (2019). "Ultramontanism, Nationalism, and the Fall of Saigon: Historicizing the Vietnamese American Catholic Experience". American Catholic Studies. 130 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1353/acs.2019.0014. S2CID 166860652.

- Hoang, Tuan (2022). ""Our Lady's Immaculate Heart Will Prevail": Vietnamese Marianism and Anticommunism, 1940–1975". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 126–157. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.126. S2CID 250515678.

- Keith, Charles (2008). "Annam Uplifted: The First Vietnamese Catholic Bishops and the Birth of a National Church, 1919–1945". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 3 (2): 128–171. doi:10.1525/vs.2008.3.2.128.

- Luria, Keith P. (2017b). "Catholic Marriage and the Customs of the Country: Building a New Religious Community in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam". French Historical Studies. 40 (3): 457–473. doi:10.1215/00161071-3857016.

- Makino, Motonori (2013). "Local Administrators and the Nguyen Dynasty's Suppression of Christianity during the Reign of Minh Mang 1820–1841". Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko. 71 (71): 109–139.

- Nguyen, Phi-Vân (2016). "Fighting the First Indochina War Again? Catholic Refugees in South Vietnam, 1954–59". Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 31 (1): 207–246. doi:10.1355/sj31-1f.

- Nguyen, Thao (2019). "Resistance, Negotiation and Development: The Roman Catholic Church in Vietnam, 1954–2010". Studies in World Christianity. 25 (3): 297–323. doi:10.3366/swc.2019.0269.

- Nguyen-Marshall, Van (2009). "Tools of Empire? Vietnamese Catholics in South Vietnam". Journal of the Canadian Historical Association. 20 (2): 138–159. doi:10.7202/044402ar.

- Ngô, Lân (2022). "Prophets and Zealots: The 1873 Synodal Document, Nonconformist Confucianism, and the Vietnamese Clergy". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 64–92. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.64. S2CID 250515444.

- Nyan, Francis (2011). "Half-Brothers: The Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes in Vietnam, 1900–1945". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 6 (3): 1–43. doi:10.1525/vs.2011.6.3.1.

- Ramsay, Jacob (2004). "Extortion and Exploitation in the Nguyễn Campaign against Catholicism in 1830s–1840s Vietnam". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 35 (2): 311–328. doi:10.1017/S0022463404000165. S2CID 143702710.

- Tran, Anh Q. (2022). "Catholicism and the Development of the Vietnamese Alphabet, 1620–1898". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 9–37. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.9. S2CID 250513843.

- Trân, Claire Thi Liên (2005). "The Catholic Question in North Vietnam: From Polish Sources, 1954–56". Cold War History. 5 (4): 427–449. doi:10.1080/14682740500284747. S2CID 154280435.

- Trân, Claire Thi Liên (2013). "The Challenge for Peace within South Vietnam's Catholic Community: A History of Peace Activism". Peace & Change: A Journal of Peace Research. 38 (4): 446–473. doi:10.1111/pech.12040.

- Trân, Claire Thi Liên (2020). "The Role of Education Mobilities and Transnational Networks in the Building of a Modern Vietnamese Catholic Elite (1920s–1950s)". Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 35 (2): 243–270. doi:10.1355/sj35-2c. S2CID 225458221.

- Trần, Claire Thị Liên (2022). "Thanh Lao Công [Young Christian Workers] in Tonkin, 1935–1945: From Social to Political Activism". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 93–125. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.93. S2CID 250508860.

Supplementary sources

- Alberts, Tara (2013a). Conflict and Conversion: Catholicism in Southeast Asia, 1500–1700. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199646265.

- Daughton, James P. (2006a). An Empire Divided: Religion, Republicanism, and the Making of French Colonialism, 1880–1914. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195305302.

- Hoang, Tuan (2022a). "New Histories of Vietnamese Catholicism". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 1–8. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.1. S2CID 250519054.

- Michaud, Jean (2004). "Missionary Ethnographers in Upper-Tonkin: The Early Years, 1895–1920". Asian Ethnicity. 5 (2): 179–194. doi:10.1080/1463136042000221876. S2CID 55551641.

- Nguyen, Phi-Vân (2018). "A Secular State for a Religious Nation: The Republic of Vietnam and Religious Nationalism, 1946–1963". The Journal of Asian Studies. 77 (3): 741–771. doi:10.1017/S0021911818000505.

- Nguyen, Phi-Vân (2021). "Victims of Atheist Persecution: Transnational Catholic Solidarity and Refugee Protection in Cold War Asia". In Meyer, Birgit; Veer, Peter van der (eds.). Refugees and Religion: Ethnographic Studies of Global Trajectories. Bloomsbury. pp. 51–67. ISBN 9781350167162.

- Pham, Ly Thi Kieu (2019). "The True Editor of the Manuductio ad linguam Tunkinensem (Seventeenth- to Eighteenth-Century Vietnamese Grammar)". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 14 (2): 68–92. doi:10.1525/vs.2019.14.2.68. S2CID 181585717.

- Volkov, Alexei (2008). "Traditional Vietnamese Astronomy in Accounts of Jesuit Missionaries". In Saraiva, Luís; Jami, Catherine (eds.). The Jesuits, the Padroado and East Asian Science (1552–1773). History of Mathematical Sciences: Portugal and East Asia. Vol. III. World Scientific Publishing. pp. 161–185. doi:10.1142/9789812771261_0007. ISBN 9789814474269.

- Volkov, Alexei (2012). "Evangelization, Politics, and Technology Transfer in the 17th-Century Cochinchina: The Case of João da Cruz". In Saraiva, Luís (ed.). Europe and China: Science and the Arts in the 17th and 18th Centuries. History of Mathematical Sciences: Portugal and East Asia. Vol. IV. World Scientific Publishing. pp. 31–67. doi:10.1142/9789814390446_0002. ISBN 9789814401579.

- Trần Văn Toàn (2003). "Tam giáo chư vọng (1752) – Một cuốn sách viết tay bàn về tôn giáo Việt Nam". Nghiên cứu Tôn giáo (1 #19): 47–54. Viện Nghiên cứu Tôn giáo, Viện Hàn lâm Khoa học Xã hội Việt Nam.

- Trần Văn Toàn (2007). "Western Missionaries' Overview on Religion in Tonkin (North of Vietnam) in the 18th Century". Religious Studies Review. 1 (3): 14–28. Institute for Religious Studies, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences.

- Trần Văn Toàn (2005). "Tôn giáo Việt Nam trong thế kỉ XVIII theo cái nhìn tổng hợp của giáo sĩ phương Tây đương thời ở Đàng Ngoài". Nghiên cứu Tôn giáo (1 #31): 60–68.

- Trần Văn Toàn (2005). "Tôn giáo Việt Nam trong thế kỉ XVIII theo cái nhìn tổng hợp của giáo sĩ phương Tây đương thời ở Đàng Ngoài (tiếp theo)". Nghiên cứu Tôn giáo (2 #32): 15–20.

- Trần, Claire Thị Liên (2013a). "Communist State and Religious Policy in Vietnam: A Historical Perspective". Hague Journal on the Rule of Law. 5 (2): 229–252. doi:10.1017/S1876404512001133. S2CID 154978637.

- Trần, Claire Thị Liên (2014). "H-Diplo Article Reviews No. 485 – 'Phát Diệm Nationalism, Religion and Identity in the Franco-Việt Minh War'". H-Net.

- Tran, Thi Phuong Phuong (2020). "The first encounters of Vietnam with the Western literature in the 17th century (a case study of Jeronimo Maiorica's Nôm hagiographic writings)". Russian Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 4 (4): 71–80. doi:10.24411/2618-9453-2020-10035.

- Dror, Olga, ed. (2002). Opusculum de Sectis apud Sinenses et Tunkinenses: A Small Treatise on the Sects among the Chinese and Tonkinese. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780877277323.

- Dror, Olga; Taylor, K. W., eds. (2006). Views of Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Christoforo Borri on Cochinchina and Samuel Baron on Tonkin. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780877277712.

External links

- Catholic Church in Vietnam on GCatholic

- Catholic Church in Vietnam on Catholic-Hierarchy

- "Catholic processions in Vietnam" photo collection

.jpg.webp)