Villa of the Papyri

The Villa of the Papyri (Italian: Villa dei Papiri, also known as Villa dei Pisoni and in early excavation records as the Villa Suburbana) was an ancient Roman villa in Herculaneum, in what is now Ercolano, southern Italy. It is named after its unique library of papyri (or scrolls), discovered in 1750.[1] The Villa was considered to be one of the most luxurious houses in all of Herculaneum and in the Roman world.[2] Its luxury is shown by its exquisite architecture and by the large number of outstanding works of art discovered, including frescoes, bronzes and marble sculpture[3] which constitute the largest collection of Greek and Roman sculptures ever discovered in a single context.[4]

| Villa of the Papyri | |

|---|---|

Villa dei Papiri | |

Villa of the Papyri | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Ercolano |

| Country | Italy |

| Coordinates | 40.806761348109745°N 14.345911100666743°E |

It was situated on the ancient coastline below the volcano Vesuvius with nothing to obstruct the view of the sea. It was perhaps owned by Julius Caesar's father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus.[5][6] In 1908, Barker suggested that Philodemus may have been the owner.[7]

In AD 79, the eruption of Vesuvius covered all of Herculaneum with up to 30 metres (98 ft) of volcanic material from pyroclastic flows. Herculaneum was first excavated in the years between 1750 and 1765 by Karl Weber by means of tunnels. The villa's name derives from the discovery of its library, the only surviving library from the Graeco-Roman world that exists in its entirety.[8] It contained over 1,800 papyrus scrolls, now carbonised by the heat of the eruption, the "Herculaneum papyri".

Most of the villa is still underground, but parts have been cleared of volcanic deposits. Many of the finds are displayed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. The Getty Villa museum in Malibu, California, is a reproduction of the Villa of the Papyri.

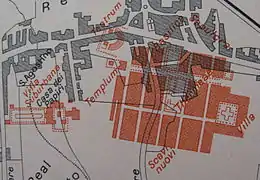

Layout

_(14596218878).jpg.webp)

The villa is located a few hundred metres from the nearest house in Herculaneum. Although it now lies inland, before the volcanic eruption of October 79 A.D., the structure occupied more than 250 metres (820 ft) of coastline along the Gulf of Naples. On the other sides it was surrounded by a closed garden, vineyards and woods. The villa had four levels beneath the main floor, arranged in terraces overlooking the sea.[9] It has recently been ascertained that the main floor was 16 m (52 ft) above sea level in antiquity.

The villa's layout is an expanded version of the traditional Campanian villa suburbana. One entered through the fauces and proceeded to the atrium, which functioned as an entrance hall and a means of communication with the various parts of the house. The entrance opened with a columned portico on the sea side.

After passing through the tablinum, one arrived at the first peristyle, made up of ten columns on each side, with a swimming pool in the centre. In this area were found the bronze herm adapted from the Doryphorus of Polykleitos and the herm of an Amazon made by Apollonios son of Archias of Athens.[10] The large second peristyle could be reached by passing through a large tablinum in which, under a propylaeum, was the archaic statue of Athena Promachos. A collection of bronze busts were in the interior of the tablinum. These included the head of Scipio Africanus.[2]

The living and reception quarters were grouped around the porticoes and terraces, giving occupants ample sunlight and a view of the countryside and sea. In the living quarters, bath installations were brought to light, and the library of rolled and carbonised papyri placed inside wooden capsae, some of them on ordinary wooden shelves and around the walls and some on the two sides of a set of shelves in the middle of the room.[2]

The grounds included a large area of covered and uncovered gardens for walks in the shade or in the warmth of the sun. The gardens included a gallery of busts, hermae and small marble and bronze statues. These were laid out between columns amid the open part of the garden and on the edges of the large swimming bath.[2]

Works of art

The luxury of the villa is evidenced not only by the many works of art, but especially by the large number of rare bronze statues found there, all masterpieces. The villa housed a collection of at least 80 sculptures of magnificent quality,[12] many now conserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.[2] Among them is the bronze Seated Hermes, found at the villa in 1758. Around the bowl of the atrium impluvium were 11 bronze fountain statues depicting Satyrs pouring water from a pitcher and Amorini pouring water from the mouth of a dolphin. Other statues and busts were found in the corners around the atrium walls.[2]

Five statues of life-sized bronze dancing women wearing the Doric peplos sculpted in different positions and with inlaid eyes are adapted Roman copies of originals from the fifth century BC. They are also hydrophorai drawing water from a fountain.

Epicureanism and the library

The owner of the house, perhaps Calpurnius Piso, established a library of a mainly philosophical character. It is believed that the library might have been collected and selected by Piso's family friend and client, the Epicurean Philodemus of Gadara, although this conclusion is not certain.[5][13] Followers of Epicurus studied the teachings of this moral and natural philosopher. This philosophy taught that man is mortal, that the cosmos is the result of accident, that there is no providential god, and that the criteria of a good life are pleasure and temperance. Philodemus' connections with Piso brought him an opportunity to influence the young students of Greek literature and philosophy who gathered around him at Herculaneum and Naples. Much of his work was discovered in about a thousand papyrus rolls in the philosophical library recovered at Herculaneum. Although his prose work is detailed in the strung-out, non-periodic style typical of Hellenistic Greek prose before the revival of the Attic style after Cicero, Philodemus surpassed the average literary standard to which most epicureans aspired. Philodemus succeeded in influencing the most learned and distinguished Romans of his age. None of his prose work was known until the rolls of papyri were discovered among the ruins of the Villa of the Papyri.[5]

.jpg.webp)

At the time of the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, the valuable library was packed in cases ready to be moved to safety when it was overtaken by a pyroclastic flow; the eruption eventually deposited some 20–25 m of volcanic ash over the site, charring the scrolls but preserving them – the only surviving library of Antiquity – as the ash hardened to form tuff.[2]

Excavations

The House of Bourbon under King Charles VII of Naples issued excavations following the re-discovery of Herculaneum in 1738.[14][15] Excavation work at Herculaneum was done through digging tunnels, and piercing walls, in an attempt to find treasures like paintings, statues and other ornaments to be exhibited in the Museum Herculanense, part of the King's Royal Palace in Portici.[16]

The Villa of the Papyri was discovered in 1750 by farmers when digging a well. The following excavation work was conducted first by Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre and later by the Swiss engineer Karl Jakob Weber, who worked under Alcubierre for King Charles VII of Naples.[1] Initially the first papyri scrolls which were obtained in 1752 were thrown away due to the high number, then Bernardo Tanucci advised the King to study them. The King subsequently established a commission for the study of the papyri.[17]

Camillo Paderni who took part at the excavations and was possibly the first to transcribe papyri, noted in a letter dated 1754, "...in five places, where we might have expected to meet with busts or statues, the antients had been digging before us, and taken them away. The method, whereby they regulated their searches, seems to have been this: where the ground was pretty easy to work, they dug through it and where they met with the solid lava they desisted. But whether they were in want of money, or of hands, they certainly did not perfect their intention; as is plain from the statues, which we have found."[18]

Excavations were halted in 1765 due to complaints from the residents living above. The exact location of the villa was then lost for two centuries.[9] In the 1980s work on re-discovering the villa began by studying 18th century documentation on entrances to the tunnels and in 1986 the breakthrough was made through an ancient well. The backfill from some of the tunnels was cleared to allow re-exploration of the villa when it was found that the parts of the villa that survived the earlier excavations were still remarkable in quantity and quality.

Excavation to expose part of the villa was done in the 1990s and revealed two previously undiscovered lower floors to the villa[9] with frescoes in situ. These were found along the southwest-facing terrace of about 4 metres height. The first row of rooms lying below the arcade was evidenced by a series of rectangular openings along the façade.

Limited excavations recommenced at the site in 2007 to preserve the remains when carved parts of wood and ivory furniture were discovered. Since then limited public access became available.

As of 2012, there are still 2,800 m2 left to be excavated of the villa. The remainder of the site has not been excavated because the Italian government is preferring conservation to excavation, and protecting what has already been uncovered.[19] David Woodley Packard, who has funded conservation work at Herculaneum through his Packard Humanities Institute, has said that he is likely to be able to fund excavation of the Villa of the Papyri when the authorities agree to it; but no work will be permitted on the site until the completion of a feasibility report, which has been in preparation for some years. The first part of the report emerged in 2008 but included no timetable or cost projections, since the decision for further excavation is a political one.[20] Politics involve excavation under inhabited areas in addition to unspecified but reported[21] references to mafia involvement.

Using multi-spectral imaging, a technique developed in the early 1990s, it is possible to read the burned papyri. With multi-spectral imaging, many pictures of the illegible papyri are taken using different filters in the infrared or in the ultraviolet range, finely tuned to capture certain wavelengths of light. Thus, the optimum spectral portion can be found for distinguishing ink from paper on the blackened papyrus surface.

Non-destructive CT scans will, it is hoped, provide breakthroughs in reading the fragile unopened scrolls without destroying them in the process. Encouraging results along this line of research have been obtained, which use phase-contrast X-ray imaging.[22][23][24][25] According to authors, "this pioneering research opens up new prospects not only for the many papyri still unopened, but also for others that have not yet been discovered, perhaps including a second library of Latin papyri at a lower, as yet unexcavated level of the Villa."[26]

J. Paul Getty Museum

In 1970, oil billionaire J. Paul Getty engaged the architectural firm of Langdon and Wilson to create a replica of the Villa dei Papiri to serve as a museum where his collection of antiquities would be displayed.

Based on Weber's plans published in Le Antichità di Ercolano, the museum was built on Getty's Malibu ranch in 1972–1974. Architectural consultant Norman Neuerburg and the curator of Getty's antiquities, Jiří Frel, worked closely with Getty and the architects to ensure the accuracy of the museum building's design .

Since the Villa dei Papiri was unexcavated, Neuerburg based many of the villa's architectural and landscaping details on elements from other ancient Roman houses in the towns of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae.[27] For example, the mosaic fountain in the museum's garden peristyle replicates the one in the Nymphaeum of the House of the Large Fountain at Pompeii.

In 1997, the Getty Museum was relocated to the Getty Center. The Malibu villa was renovated and reopened in 2006. The reconceived Getty Villa, as it is now called, serves as an annex dedicated to the display of the museum's antiquities and as a centre for the study of ancient art.

In modern literature

The opening pages of the 1850 fictional work A Few Days in Athens claim to be "the translation of a Greek Manuscript discovered in Herculaneum". The novel was written by Frances Wright, a female philosopher who was mentored by the Epicurean American founding father, Thomas Jefferson, and it unapologetically defends Epicurus' character, Epicurean philosophy, and secular values.

Several scenes in Robert Harris' bestselling novel Pompeii are set in the Villa of the Papyri, just before the eruption engulfed it. The villa is mentioned as belonging to Roman aristocrat Pedius Cascus and his wife Rectina. (Pliny the Younger mentions Rectina, whom he calls the wife of Tascius, in Letter 16 of book VI of his Letters.) At the start of the eruption Rectina prepares to have the library evacuated and sends urgent word to her old friend, Pliny the Elder, who commands the Roman Navy at Misenum on the other side of the Bay of Naples. Pliny immediately sets out in a warship, and gets in sight of the villa, but the eruption prevents him from landing and taking off Rectina and her library – which is thus left for modern archaeologists to find.

Works of art

Sculpture from the Villa

According to the 1908 publication Buried Herculaneum by Ethel Ross Barker, there were busts of Athene Gorgolopha, Archaistic Pallas, Archaic Apollo, Head of an Amazon, Dionysus or Plato (? Poseidon), Doryphorus, Mercury, Homer, Ptolemy Alexander (Alexander the Great?), Ptolemy Philadelphus, Ptolemy Soter I (Seleucus Nicator I), and the mythological Danaids and others.[28]

Busts

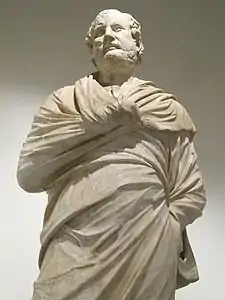

Statue of Aeschines, Greek statesman and one of the ten Attic orators, found in the large peristyle

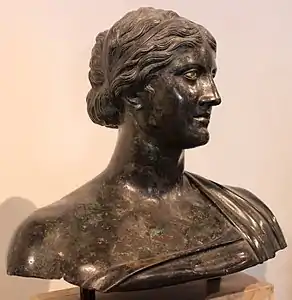

Statue of Aeschines, Greek statesman and one of the ten Attic orators, found in the large peristyle.jpg.webp) Artemis or Berenike found in the garden of the villa

Artemis or Berenike found in the garden of the villa

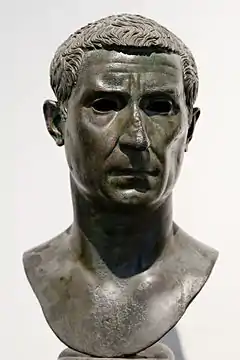

Unidentified Hellenistic ruler found in the atrium, perhaps Ptolemy Alexander, Ptolemy Epiphanes, or Nicomedes I of Bithynia.

Unidentified Hellenistic ruler found in the atrium, perhaps Ptolemy Alexander, Ptolemy Epiphanes, or Nicomedes I of Bithynia. Lucius Calpurnius Piso Pontifex found in the villa's tablinum

Lucius Calpurnius Piso Pontifex found in the villa's tablinum Herm with head of Doryphoros found in the square peristyle

Herm with head of Doryphoros found in the square peristyle

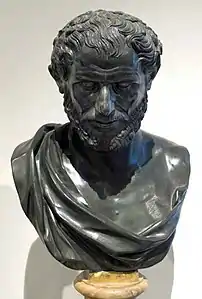

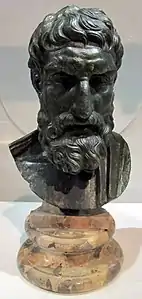

Tentatively identified as Democritus, this portrait from the square peristyle has also been suggested to be Aristotle, Solon, Philopoemen, or Heraclitus.

Tentatively identified as Democritus, this portrait from the square peristyle has also been suggested to be Aristotle, Solon, Philopoemen, or Heraclitus. Bust of Ptolemy Apion from the square peristyle

Bust of Ptolemy Apion from the square peristyle

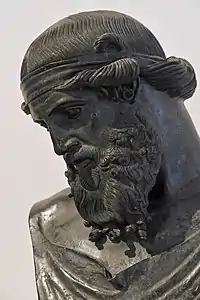

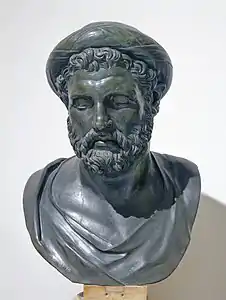

Bearded man with turban originally identified as Archytas of Tarentum but now considered to be Pythagoras

Bearded man with turban originally identified as Archytas of Tarentum but now considered to be Pythagoras Seleukos I Nikator, unknown locale within the villa

Seleukos I Nikator, unknown locale within the villa So-called Young Commander found in the rectangular peristyle, now unidentified Hellenistic ruler, or Eumenes II, founder of the Library of Pergamum.

So-called Young Commander found in the rectangular peristyle, now unidentified Hellenistic ruler, or Eumenes II, founder of the Library of Pergamum.

.jpg.webp)

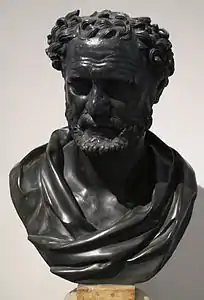

Epicurus, Roman copy of 250 BCE original

Epicurus, Roman copy of 250 BCE original Possibly Heraclitus or Empedocles from the square peristyle

Possibly Heraclitus or Empedocles from the square peristyle Ptolemaic ruler, probably Ptolemy II Philadelphus

Ptolemaic ruler, probably Ptolemy II Philadelphus

Statues

Statue of a drunken satyr from the Villa

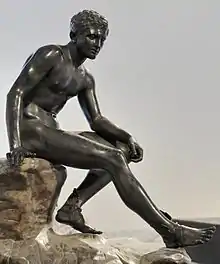

Statue of a drunken satyr from the Villa.jpg.webp) Hermes in repose or resting

Hermes in repose or resting Bronze athletes identified as either runners or wrestlers from the square peristyle

Bronze athletes identified as either runners or wrestlers from the square peristyle.jpg.webp) Sleeping satyr, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum

Sleeping satyr, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum Fawn

Fawn Pig

Pig Group of Pan and a goat, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum (now in the Secret Room at the Naples National Archaeological Museum)

Group of Pan and a goat, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum (now in the Secret Room at the Naples National Archaeological Museum) Roman notable, square peristyle, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum

Roman notable, square peristyle, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum.jpg.webp) Athena – tablinum, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum

Athena – tablinum, Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum

Illustrations

Illustrations included scenes with, Head with the wreathed helmet (Pyrrhus of Epirus?), Archimedes (Archidamus III?), Attilius Regulus (Philetairus of Pergamum?), Pseudo-Seneca (Philetas of Cos?), Berenice, Heraclitus, Ptolemy Lathyrus, Ptolemy Soter II, Sappho, Warrior in a helmet, Scipio Africanus, Head of a Vestal (Woman unknown), Hannibal or Juba, and Head with a headdress.[28]

See also

- Oxyrhynchus

- Friends of Herculaneum Society which encourages interest in the Villa and sponsors further excavation at the site.

References

- True, Marion; Silvetti, Jorge (2005). The Getty Villa. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0892368419.

- Maiuri, Amedeo. Herculaneum and the Villa of the Papyri. Italy (1974): 35–39.

- "Villa of the Papyri – AD 79 eruption". Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculpture Collection, Carol C. Mattusch (Los Angeles, California, 2005), ISBN 0892367229 p. 359

- Hornblower, Simon and Antony Spawforth. Oxford Classical Dictionary. 3rd ed. New York (1996).

- "Unlocking the scrolls of Herculaneum". BBC. 2013.

- Ethel Ross Barker (1908). "Buried Herculaneum".

- Chantal, Lheureux-Prevot. "Daniel Delattre: The Herculaneum Scrolls Given to Consul Bonabarte (2010)". Napoleon.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- "Home | the Herculaneum Society".

- Stewart, Andrew. Greek Sculpture. Yale University Press (1990).

- "Buried Herculaneum". 1908.

- "Catalogue of Sculptures – AD 79 eruption". Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

- See Erlend D. MacGillivray, "The Popularity of Epicureanism in Late-Republic Roman Society", The Ancient World XLIII (2012) pp. 151–172.

- The Academy of Real Navy December 10, 1735 was the first institution to be established by Charles III for cadets, followed 18 November 1787 by the Royal Military Academy (later Military School of Naples): Buonomo, Giampiero (2013). "Goliardia a Pizzofalcone tra il 1841 ed il 1844". L'Ago e Il Filo Edizione Online (in Italian).

- Zaragoza, Barbara (2013-05-02). "The Bourbon Dynasty in Naples". Napoli Unplugged. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- De Caro, Stefano. "Excavation and conservation at Pompeii: a conflicted history" (PDF). The Journal of FastiOnline: Archaeological Conservation Series. The International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property. ISSN 2412-5229. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Koekoe, Jade (2017). "Herculaneum: Villa of the Papyri". Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Camillo Paderni (1754). "Extract of a Letter from Camillo Paderni, Keeper of the Herculaneum Museum, to Thomas Hollis, Esq; Relating to the Late Discoveries at Herculaneum". Royal Society of London. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- See conservation issues of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

- Feasibility Study

- In search of Western civilisation's lost classics Archived 2008-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Australian, August 6, 2008

- Vergano, Dan (January 22, 2015). "X-Rays Reveal Snippets From Papyrus Scrolls That Survived Mount Vesuvius". National Geographic.

- Bukreeva, I.; et al. (2016). "Enhanced X-ray-phase-contrast-tomography brings new clarity to the 2000-year-old 'voice' of Epicurean philosopher Philodemus". arXiv:1602.08071 [physics.soc-ph].

- Mocella V, et al. (2015). "Revealing letters in rolled Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast imaging". Nature Communications. 6: 5895. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.5895M. doi:10.1038/ncomms6895. PMID 25603114.

- Bukreeva I, et al. (2016). "Virtual unrolling and deciphering of Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast tomography". Scientific Reports. 6: 30364. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630364B. doi:10.1038/srep30364. PMC 5016987. PMID 27608927.

- Mocella V, et al. (2015). "Revealing letters in rolled Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast imaging". Nature Communications. 6: 5. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.5895M. doi:10.1038/ncomms6895. PMID 25603114.

- The Getty. 2005. J. Paul Getty Museum. 11 May 2007 http://www.getty.edu/visit/see_do/architecture.html.

- Ethel Ross Barker (1908). "Buried Herculaneum".

- "villa dei papiri|mann napoli". Retrieved 2023-03-20.

Further reading

- David Sider, (2005), The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum. J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 0-89236-799-7

External links

- The Villa of Papyri artifacts on view at the Naples National Archaeology Museum

- Papyri herculanensi online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- The Friends of Herculaneum Society

- Bourbon Excavation Excavation of the Villa Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Philodemus Project website

- Roman Herculaneum website

- "Millionaire to fund dig for lost Roman library", The Sunday Times (London) February 13, 2005

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Henry Baumgartner, "New light on ancient scrolls" 2002

- J. Paul Getty Museum

- In search of Western civilisation's lost classics, The Australian, August 6, 2008

- 2015 New Yorker article about the villa