Villa of Domitian

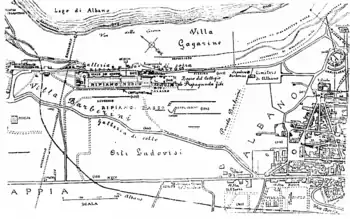

The Villa of Domitian, known as Albanum Domitiani or Albanum Caesari in Latin, was a vast and sumptuous Roman villa or palace built by emperor Domitian (r. 81–96 AD). It was situated 20 km (12 mi) from Rome, high in the Alban Hills where summer temperatures are more comfortable. It faced west overlooking the sea and Ostia. To travellers on the via Appia it would have made an impressive sight.[2]

It gained a notorious reputation among ancient authors[3][4] from Domitian's rule but this may have been unjust.[5][6]

It was one of several palaces developed by Domitian outside Rome, such as that "at Circeii" (Sabaudia).

Today the remains of the villa are located mostly within the papal Villa Barberini property,[7] the most prominent of the villas in the pontifical estate of Castel Gandolfo, and the rest in the towns of Castel Gandolfo and Albano Laziale. The Villa Barberini gardens are open to visitors.[8]

The remains have not been excavated and a complete plan is not available, hence the papers of Lugli in 1913-20[9] are still the basis of later work.

History

The legendary nearby capital of the Latin League, Alba Longa, was completely destroyed in the 6th c. BC becoming part of the Ager Albanus, and Latium vetus was annexed to Rome.

With progressive Roman expansion, the Alban Hills became home to numerous patrician suburban villas. In particular the remains of two large villas on the Via Appia Antica, one attributed to Publius Clodius Pulcher[10] in Herculanum (today in the garden of the Villa Santa Caterina of the Pontifical North American College) and the other to Pompey (Pompeo Albano, now in the municipal public park of Villa Doria) have been found.[11] In addition various Republican-era villas nestled on the banks of the lake and beyond. Many of these properties eventually became imperial property: by the time of Augustus, the extraordinary concentration of villas gave birth to the term Albanum Caesari.

The first imperial villa estate here was inhabited by Tiberius, then Caligula and Nero.[12]

The work of Domitian

Domitian settled here on a permanent basis, and decided to build a new main complex to the villa in the most panoramic position towards both the sea and the lake, and featuring lavish new structures such as a garden-stadium and theatre. Probably the project was entrusted to Rabirius, architect of the Palace of Domitian on the Palatine.

Martial mentions the villa as one of Domitian's favoured resorts.[13] Suetonius says Domitian had a passion for archery which he practised there[14] and Pliny suggests he held boating parties on the lake.[15]

On the death of Domitian the villa was rarely used by his imperial successors. Some modifications are dated to the second century and in particular to the eras of Trajan and Hadrian. Marcus Aurelius lived there a few days using the villa as a refuge during the riots that took place in 175 AD.

Abandonment

The African Emperor Septimius Severus built the grandiose legionary fortress of Castra Albana in 197 AD on the edge of the imperial properties for the Legio II Parthica. However, decline of the villa also began at this time.

The Parthian legionaries and their families established around the camp began to plunder the villa structures in order to use the material for new construction, thus giving rise to the village that would later become Albano Laziale. A second town developed on the northern edge of the imperial properties: in the Middle Ages it was called Cuccurutus and gave rise to the village Castel Gandolfo.

The Liber Pontificalis records the donation of virtually all imperial property and much of the surrounding area by Emperor Constantine I to the cathedral of St. John the Baptist (identified with the Cathedral of Albano, now named after the martyr Saint Pancras), under Pope Sylvester I (314 - 335 AD). The imperial villa of Albanum was abandoned.

The villa became the quarry of marble and building materials, similar to that of other ancient buildings: its marbles were used to build and coat the Cathedral of Orvieto in the fourteenth century.

The then feudal lords, the Savelli, gave permission to dismantle the facilities of the villa in 1321: the destruction lasted 36 days. The documents of the time outline a real business behind the dismantling of these monuments: Rodolfo Lanciani drew inspiration from these careful studies of smoke to obtain an exemplum on the reuse of the immense marble and stone material of ancient monuments of Rome and its surroundings.

Rediscovery

Pope Urban VIII (1623–1644) was the first pontiff to holiday in Castel Gandolfo, the Papal Palace; his nephew Taddeo Barberini bought the villa in 1631 which had belonged to Scipione Visconti, and which contained the most significant contents of Domitian's Villa. The most striking views of the ruins overgrown by vegetation, such as the cryptoporticus and nymphaeum, were described by scholars and diarists from the 15th c. onwards and reproduced in engravings and paintings.

Giuseppe Lugli (1890–1967) published four volumes until 1922 which, with his topographic surveys, are still the main source of information on the villa. In 1919 he made the first archaeological survey aboard the airship "Roma ", accompanied by the director of the British School of Rome, Thomas Ashby.

In 1929 the Lateran Treaty recognised the 55 hectares of the Pontifical Villas of Castel Gandolfo between the extraterritorial zone of the Holy See in Italy: most of the ruins of the villa became part of the Vatican City State, thanks to the sale of Villa Barberini to the Holy See, historically linked to the papal complex, but until then alien to it.

The Pontifical Villas were subjected to a radical reorganisation at the behest of Pope Pius XI and even the archaeological inventories, such as the cryptoporticus and the road of the nymphaea, were cleaned and incorporated.

Description

The villa-estate was built on the outside slope of the rim of the ancient volcanic crater filled by Lake Albano (between 100,000 and 5,000 years ago). The imperial property included most of today's municipalities of Castel Gandolfo and Albano Laziale. Quite possibly it extended north to at least Bovillae (XIII milestone of Appia Antica), in the south up to Aricia (XVI mile), or over 6 km2 according to Giuseppe Lugli. In the opinion of Lugli under Domitian the various villas in the imperial property were brought together in one single property, such as the villa attributed to Pompey, the remains of which are now included within the residential area of Villa Doria at Albano.

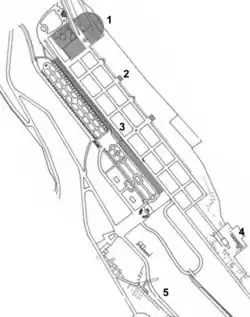

The villa was built at least three terraces,[16] a common practice for large patrician Roman villas in the hills: for example the nearby so-called villa of Lucullus in Frascati. The terraces of the villa are narrow and about 500 m (1,600 ft) long.

The third terrace from the bottom was reserved for cisterns with an especially large one of 58 x 11 m, and many water-pipes were found here stamped with Domitian's name.[17]

The palace proper stood on the second terrace, on the site of the present church of St. Francis of Assisi and the adjoining building of Propaganda Fide. Northwest of it the terrace had a panoramic view of the sea (west).

Finally, on the lower terrace were the garden-hippodrome and the entrances to the villa.

There are also buildings over the estate: the nymphaea and the docks on the lake shore, the hillside terrace, cisterns and the three aqueducts from Palazzolo, the access road network, the nymphaeum of the Rotunda in the centre of Albano converted into a Catholic church.

Other remains of a villa of Tiberian age, but inhabited until the fifth century, have been found to the southwest in Cavallacci, at the ring road of Albano. To the east, however, probably the imperial possessions included the entire Lake Albano with the many villas built in the Republican era on the crater (the so-called Augusto Palazzolo, one attributed to Seneca not far away, and others between Marino and Castel Gandolfo).

The palace

The palace building had three stories, as shown by the remains of a staircase seen by Lugli. All the walls are made of brickwork reinforced every 80 cm and do not appear to have used opus reticulatum, suggesting a 1st c. AD or later date.

The building was structured around three courtyards (probably triclinium, peristyle and tablinum) called "atria" by Rosa. This feature allowed Lugli to recognise the analogy with the complex of Domitian's palace on the Palatine in Rome. Around these spaces must have been all the rooms used by the imperial court during their long periods of stay.

The baths were recognised thanks to the abundance of clay pipes etc. and are located in the righthand central atrium, probably the peristyle.

Close to the villa was a passage through the hill to a 2-story belvedere over the Alban Lake.[18]

The Avenue of the Nymphaea

This 1 km-long avenue along the terrace extending northwest from the palace and leading to the theatre is one of the most characteristic fearures of the imperial villa. It is flanked on the northeast side by the great wall supporting the upper terrace into which are inserted four exedras, identified as nymphaea. Near the midpoint of this wall is a 100 m-long tunnel, dug through the peperino rock of the ridge of the crater in a gigantic task to allow the emperor to more easily reach the lake-side of the estate where there was another terrace. It has only one vertical shaft towards the middle.

The first nymphaeum from the south is rectangular, 6.2 m deep and has thirteen niches in the walls; the second and the fourth, semicircular, are 2.6 m and 6.85 m wide and have seven niches; the third, rectangular, is 5.5 m with thirteen niches, like the first.[19]

In some places wall plaster remains (often 3 cm thick) and even, at least at the time of Lugli, traces of colour.

The theatre

The theatre, although accommodating only 500 spectators, is one of the most significant buildings of the villa, with its exceptional marble decoration (reconstructed in the museum of Villa Barberini) and extraordinary stucco relief panels in the hall of the auditorium, a frieze consisting of thirteen panels depicting themes related to theatre and one of the most important testimonies to the Flavians, like the paintings of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The stucco decorations are in perspective, similar to painting of the fourth style. The theatre steps were crowned with a particularly elaborate and sumptuous columned portico, together with a series of small nymphaea lavishly decorated in marble opus sectile floors. The decoration of the pulpit was particularly intricate with large panels of marble opus sectile. The treads of the steps were slabs of giallo antico which was also used for the corbels. Pavonazzo marble from Phrygia was used for the balustrades which were decorated with dolphins and actors wearing masks.

The auditorium was built into the hill, while the orchestra and the stage were on the floor of the second terrace. It was built according to all the criteria of the acoustics of the time, facing the west to avoid the interference of the turbulent winds of the north and south. The orchestra's radius to the first seat was of 5.9 m, just 20 Roman feet: therefore Lugli was able to calculate that the total radius of the semicircle of the theatre was 25 m.

Some rooms date to the age of Hadrian and witness the continuity of use at least until completion of Villa Adriana in Tivoli.

The first excavation of the theatre was in 1657 by Leonardo Agostini for Cardinal Barberini. Lugli began studying theatre in 1914 and adjourned his studies in 1918 after the refurbishment of the Villa Barberini brought to light other ruins; another part of the auditorium hall with stucco panels was discovered in 1917. It is the only building to be investigated recently.[20]

The third terrace

The third terrace was the largest and most segmented, now partially occupied by the Garden of Villa Barberini.

The Cryptoporticus

The cryptoporticus at the side of the 3rd terrace supported the front of the second terrace and originally ran for the entire length up to the forecourt of the theatre.[21] Although now very truncated it still has a length of 120 m and 7.45 m width and is probably the largest known cryptoporticus in any villa around Rome, certainly dwarfing any of those of the Villa Adriana at Tivoli.[22]

The vaulted ceiling was reinforced with brickwork rings and coffered in stucco of which few traces remain.[23] The east side is carved in part from the rock itself, while the west is pierced by windows providing light: Lugli noted with admiration how each window corresponds to a niche on the other side. The ancient floor was about a metre and a half lower than the current one. At the north end was the statue of Polyphemus found in the Bergantino nymphaeum on the lake shore.

It is likely that the north-western part was damaged at end of the 2nd or in the early 3rd century by one of the earthquakes in this area and collapsed later, as it had large windows weakening the structure unlike the surviving section.[24]

Various access routes from the Appian Way to the villa converged towards this cryptoporticus and therefore it was a sort of long covered entrance (via tecta).

The "Hippodrome"

The garden in the shape of a hippodrome is a large north-south space 75 m (246 ft) wide bounded by brick walls. The north wall forms a semi-circle at the centre of which was a fountain, 7.1 m (23 ft) long and 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) wide, decorated with stucco.[25] It has been shown to be a garden from the water cisterns and decoration, similar to that of the Palace of Domitian on the Palatine.[26]

Under the substructures is a cistern 41 m (135 ft) long. Not far from the structures were found a number of areas of equal width of 4.2 m (14 ft) long and 2.95 m (9 ft 8 in) set against the foundation wall of the second terrace under the cryptoporticus.

Lakeview terrace

100 m from the palace in one of the nineteenth-century villas are the remains of a terrace overlooking the lake. Only two walls of substructure remain, spaced from one another by 15 m. The fact that these structures are in opus reticulatum suggests that this is an early villa, dating from the late Republican era, embedded in the structure of the later villa.[27] Probably between the two walls was a road leading down to the lake shore.

The lakeside terrace is accessed through the tunnel dug into the lava rock from the Avenue of the Nymphaea to save the emperor from climbing the hill to see the lake below. In 1910 the tunnel was cleared from the earth that had filled over the centuries, but since it ended outside the papal property it was closed at the villa Barberini wall. The height of the entrance on the side of Villa Barberini is 2.4 m. The outlet on the side of the lake below was tracked down by Lugli in the wall of the terrace which includes a large brickwork arch 3.75 m wide.[28]

The Doric nymphaeum

The beautiful Doric nymphaeum on the descent from Castel Gandolfo towards the lake is dated to the Republican age. It has similarities to the nympheum of Egeria at Caffarella.

The nymphaeum is a rectangular space of 11 x 6 m with the barrel-vaulted ceiling reaching a height of 8 m (26 ft), and with niches arranged in two rows. The order of the first floor columns is Doric (hence the name of the fountain), that of the second Ionic. At the centre in front of the entrance is an arch leading into a natural cave, probably an ancient spring. There used to be spectacular water works with larger and smaller waterfalls and channels fed with water from one of the aqueducts and from a series of cisterns and pipes installed behind the central back wall.

Many scholars believe that it could be the “sacella” (sacrarium) described by Cicero and built by Clodius on the ruins of the ancient Alba Longa. The Nymphaeum is faced with opus reticulatum.

The Doric nymphaeum was probably rediscovered in 1723, since it is in a memoire of Francesco de Ficoroni (the discoverer of the famous Cista Ficoroni).

The Bergantino nymphaeum

On the western shore of Lake Albano, 2 km after the Doric nymphaeum is a circular cave of 17 m (56 ft) diameter. Originally a quarry it was made into a grotto with alcoves around a pool, from which a statue of Scylla in bigio marble emerged, and the floor was completely covered with mosaics of which a few fragments remain. It was the type of nymphaeum used as a summer triclinium (dining room) in imperial villas as at Hadrian's villa, with evocative and imaginative effects and sumptuous statuary representing the saga of Ulysses and the Cyclops Polyphemus which was set at the back of the cave. Domitian recreated here features of the maritime otium villas on the Tyrrenian coast of southern Latium at Sperlonga and at Baiae.

Various parts of sculptural groups found in the nymphaeum are now kept at the Pontifical Palace in Castel Gandolfo.

The docks and shore

The first comprehensive study on the docks and neighbouring buildings was completed in 1919 by Lugli and Thomas Ashby.[29] which found a collection of docks concentrated on the western and eastern shore from Cantone to Acqua Acetosa. Here were three adjacent villas dating to the first century, each with its direct flight of steps to the lake.

The western shore starts at the junction of the 140 road to the beach at Castel Gandolfo and continues to the Bergantino nymphaeum. On this stretch are the most monumental remains including a cryptoporticus probably related to a villa, and a structure known as a beacon or lighthouse. The first part of the shore at the Doric nymphaeum is dated to the late Republican era, and one or two villas can be recognised which were subsequently incorporated into the Domitian complex.

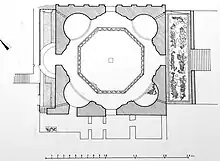

The rotonda

This unique building is located in the present Albano Laziale 2.5–3 km from the residential complex of Domitian's villa. Its excellent state of preservation makes it one of the most important monuments in Albano.

It is cylindrical in plan within a cube and with a dome, similar but smaller to the Pantheon in Rome, also replicating the oculus (central hole).[30] Its diameter is 16 m and the whole structure is made of opus mixtum.

Its position on the site of a former entrance to the imperial villa, would suggest that it was a monumental entrance and nymphaeum to the residence.[31] Inside there were playing fountains, as shown by the water pipes and pools in the niches.

Around 183 a rectangular antechamber was built in front of the original building.[32] In the Severan era (3rd century AD) it was incorporated into the perimeter wall of the Castra Albana and adapted for bathing by legionaries: to this phase belong the floor mosaics with marine animals, in a painting of scenes in a gymnasium and in ceramic water pipes found at different times below modern buildings that surround the monument. The buildings that arose around the quadrangular structure of the church collapsed with the abandonment of the Castra Albana in the 4th century.[33]

Probably between the ninth and tenth century it was converted into a place of worship, and received the Eastern image of the Madonna dating from the 6th - 7th century.

The aqueducts

Domitian's Villa is supplied from the southeast by four aqueducts coming from sources located between the towns of Palazzolo and Malafitto. In many places, ancient aqueducts still feed modern ones or have been in use until a few decades ago.

The most ancient aqueduct is the "Hundred Mouths" so named because it collects water from springs scattered over an area of about 150 m (490 ft) between the towns of Palazzolo and Malafitto; its course is a wide tunnel 1.65 m high that runs along the ridge of the lake to the Colle dei Cappuccini, which it crosses via a tunnel about 500 m long. The tunnelling work was so demanding that the builders wrongly made a reverse slope for about 100 m (330 ft) which they had to correct by raising the aqueduct floor with bricks.[34] The aqueduct disappears at the height of the old town of Albano, about 3 m below the ground in Piazza San Paolo. It is very likely that this served originally the villa of Pompey. In the Severan age it must have also served the Castra Albana as the great "Cisternoni" of the thermae are adjacent to the Rotunda and the Baths of Caracalla.

Two aqueducts have sources near Malafitto, called "high" and "low Malafitto" depending on the height at which they run. The high Malafitto aqueduct is the only one of the four definitely attributable to the Domitian era. The aqueduct had to serve the whole of the villa building and to maintain a high flow the builders had to follow a rather tortuous path through the woods of Selvotta. Finally the aqueduct passed under the Colle dei Cappuccini and ran in a section parallel to the other two aqueducts. In 1904 the last part of the aqueduct was found at the cemetery of Albano, about 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) below the surface today. From there, the tunnel emptied into the great cistern of the villa under the seat of Propaganda Fide. The tunnels not carved into the rock are made of opus reticulatum. The channel is approximately 60 cm wide and about 1.6 m tall. Along the route were found 53 circular wells, the deepest of which is 53 m (174 ft).

The low Malafitto has more opus reticulatum and different channel dimensions that suggest a period immediately subsequent to the Flavian, presumably Trajan or Hadrian. Its route runs almost parallel to the others to the cemetery of Albano but then heads towards the current town of Castel Gandolfo and it seems certain that it leads to the large Torlonia cistern in the dell'Ercolano area.

Finally, the aqueduct of Aqua Augusta was identified in 1872 by Giovanni Battista de Rossi due to five memorial stones found in different properties between the Fields of Hannibal at Rocca di Papa, and the slopes of Monte Cavo. The only possible hypothesis is that it served the Roman villa identified on the shores of Lake Albano in Palazzolo, attributed to Augustus by the 19th c. archaeologists.

Cisterns

Three cisterns were found around the palace, some of the largest cisterns of Roman times, all of which are now in the Propaganda Fide college. Two of them have been incorporated into the building, built in 1619. The larger of the two must have had 9 arches; the floor was in cocciopesto. The other smaller one had 5 arches in length. The walls of both are in opus reticulatum. Both are now underground, but originally they were at least partially uncovered.[35]

The largest of the three cisterns adjacent to the building is 123 m long overall, oriented north-south and is divided into three communicating chambers: the first 58 x 11 m, the second 35.5 and the third 29.5, both 10.4 m wide. It was served by the Malafitto alto aqueduct: the water fell into the first room from above from a sort of circular well located on the east side; from there it passed, purified from debris that fell to the bottom, to the second chamber and from there further purified into the third, from which it was ready for use. The sections not excavated in the rock are built with a wall in opus reticulatum 1.8 thick, reinforced in sections by bipedals (typical of the Domitian age).

There were also other smaller cisterns scattered around the villa and the vast estate: one was found under the hippodrome, and is 41 m long and about a couple of meters wide. Another, measuring 7.6 x 2.5 m and about 7 m high, was discovered on the shore of Lake Albano at the end of the downhill section of the current state road 140 and probably served an ancient villa incorporated into the imperial properties.

However, the largest of the cisterns unrelated to the residential complex is the so-called "Torlonia swimming pool" which was in the ancient properties of the Torlonia family, today in the village of Borgo San Paolo, between the town of Castel Gandolfo and the Via Appia Nuova. This cistern measures 43.5 x 32 m with pillars in brick and walls in mixed brickwork and peperino cubilia. However, the later construction compared to the Domitian complex is shown by the poorer reticulated appearance and by the different consistency of the mortar: therefore it is a probably a construction of the Trajan or Hadrian period, served by the coeval Malafitto Basso aqueduct.[36]

The garrison

References

- Lugli, Giuseppe. La Villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani. Italy: P. Maglione & C. Strini, 1918.

- Robin DARWALL-SMITH; ALBANUM AND THE VILLAS OF DOMITIAN; Pallas No. 40, Les annêes Domitien: 1992 à l'initiative du Groupe de recherche sur l'Antiquité Classique et Orientale (GRACO) (1994), Presses Universitaires du Midi, p 150 https://www.jstor.org/stable/43660537

- Juvenal, SATIRE 4

- Tacitus, Agricola 45

- Jones, Brian W. (1992). The Emperor Domitian. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10195-0 p. 198

- Gowing, Alain M. (1992). "Review: The Emperor Domitian". Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- Claudia Valeri, ‘Albanum Domitiani’, Domitian’s Villa in Castel Gandolfo in GOD ON EARTH: EMPEROR DOMITIAN edited by A. R. Cominesi et al. ISBN 9789088909559 https://www.sidestone.com/books/god-on-earth-emperor-domitian

- "Villa Barberini and its Garden". Museivaticani.va. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- Lugli, Giuseppe. La Villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani. Italy: P. Maglione & C. Strini, 1918

- Giuseppe Lugli, Le antiche ville dei Colli Albani prima dell'occupazione domizianea, Roma, Loescher, 1915 pp. 15-32

- Lugli 1915, pp. 33-47

- Antonio Nibby, vol. I, in Analisi storico-topografico-antiquaria della carta de' dintorni di Roma, IIª ed., Roma, Tipografia delle Belle Arti, 1848, pp. 546.

- Martial V 1.1. [cf. IV 1.5]

- Suetonius, Domitianus, 19

- Pliny ib. 82. 1-4

- Giuseppe Lugli, La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani: parte I, Roma, Maglione & Strini, 1918. pp. 13-15

- Paolo Liverani, La villa di Domiziano a Castel Gandolfo, in M. VALENTI (a cura di), Residenze imperiali nel Lazio (atti della giornata di studio - Monte Porzio Catone, 3 aprile 2004), Tuscolana – Quad. Mus. Monte Porzio Catone 2, Monte Porzio Catone 2008, pp. 53-60

- Lugli. G.: La Villa di Domiziano sui colli Albani - Part: II. Le Costruzioni centrale. BCAR 46 (1918), pp. 3-68.

- Lugli. G.: La Villa di Domiziano sui colli Albani - Part: II. Le Costruzioni centrale. BCAR 46 (1918), pp. 30-32

- Hesburg 1978/80: Hesburg H. Von. « Zur Datierung des Theaters in der Domitiansvilla von Castel Gandolfo : Archeologia Laziale 4 (1981). pp. 176-80

- Giuseppe Lugli, La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani: parte II, Roma, Maglione & Strini, 1920 pp. 57-59

- Filippo Coarelli, Guide archeologiche Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, Bari-Roma, Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli, 1981. CL 20-1848-9 p. 76.

- Antonio Nibby, vol. I, in Analisi storico-topografico-antiquaria della carta de' dintorni di Roma, IIª ed., Roma, Tipografia delle Belle Arti, 1848, p. 97

- Paolo Liverani, La villa di Domiziano a Castel Gandolfo, in M. VALENTI (a cura di), Residenze imperiali nel Lazio (atti della giornata di studio - Monte Porzio Catone, 3 aprile 2004), Tuscolana – Quad. Mus. Monte Porzio Catone 2, Monte Porzio Catone 2008, p. 56

- Lugli 1920, pp. 64-66

- ALBANUM AND THE VILLAS OF DOMITIAN; Robin DARWALL-SMITH; p. 150

- Filippo Coarelli, Guide archeologiche Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, Bari-Roma, Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli, 1981. CL 20-1848-9 p. 75

- Giuseppe Lugli, La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani: parte II, Roma, Maglione & Strini, 1920 pp. 30-32

- Lugli 1921 , pp. 17-18

- Giuseppe Lugli, La "Rotonda" di Albano, in Il tempio di Santa Maria della Rotonda , p. 67, Albano Laziale 1972.

- Pino Chiarucci, La civiltà laziale e gli insediamenti albani in particolare, in Atti del corso di archeologia tenutosi presso il Museo civico di Albano Laziale nel 1982-1983, pp. 58-59

- Filippo Coarelli, Guide archeologhe Laterza - Dintorni di Roma, Iª ed., Roma-Bari, Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli, 1981 p 88

- Alberto Terenzio et al., Il tempio di Santa Maria della Rotonda, IIª ed., Albano Laziale, Graphikcenter, 1972, pp. 38-39

- Lugli 1918 , pp. 30-33

- Lugli. G.: La Villa di Domiziano sui colli Albani - Part: II. Le Costruzioni centrale. BCAR 46 (1918), pp. 12-13

- Giuseppe Lugli, La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani: parte III, Roma, Maglione & Strini, 1921. pp 37-43