Vito Cascio Ferro

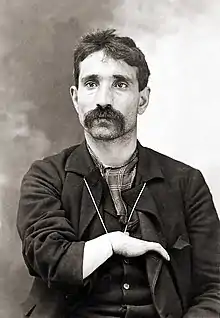

Vito Cascio Ferro or Vito Cascioferro (Italian pronunciation: [ˈviːto ˈkaʃʃo ˈfɛrro]; 22 January 1862 – 20 September 1943), also known as Don Vito, was a prominent member of the Sicilian Mafia. He also operated for several years in the United States. He is often depicted as the "boss of bosses", although such a position does not exist in the loose structure of Cosa Nostra in Sicily.

Vito Cascio Ferro | |

|---|---|

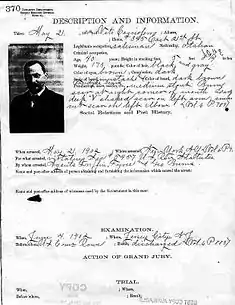

1902 mug shot of Cascio Ferro | |

| Born | 22 January 1862 |

| Died | 20 September 1943 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | Don Vito |

| Occupation(s) | Mafia boss, revenue collector |

| Spouse | Brigida Giaccone |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent(s) | Accursio Cascio Ferro Santa Ippolito |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment (1930) |

Cascio Ferro's life is full of myth and mystery. He became a legend even when he was alive, and that legend is partially responsible for creating the image of the gallant gentleman capomafia (Mafia boss).[1] He is widely considered to have been responsible for the 1909 murder of Joseph Petrosino, head of the New York City police department's Italian Squad. However, he was never convicted of the crime.

With the rise of Fascism in Italy, his untouchable position declined. He was arrested and sentenced to death in 1930 and would remain in jail until his death. There is some confusion about the exact year of his death, but according to La Stampa, Cascio Ferro died on 20 September 1943, in the prison on the island of Procida.

Early life

Although many sources have identified Cascio Ferro as a native of the rural town of Bisacquino, where he was raised, he was actually born in the city of Palermo, on 22 January 1862.[2] His parents, Accursio Cascio Ferro and Santa Ippolito, were poor and illiterate.[3] The family moved to Bisacquino when his father became a campiere (an armed guard) with the local landlord, Baron Antonino Inglese, a notorious usurper of state-owned land. The position of campiere often involved Mafiosi.[2][4][5] According to other sources, at an early age, the family moved to Sambuca Zabut, where he lived for approximately 24 years before relocating to Bisacquino, his recognized power base in the Mafia.[6]

Cascio Ferro received no formal education. When still young, he married a teacher from Bisacquino, Brigida Giaccone, who instructed him how to read and write.[1][5] He was inducted into the Mafia in the 1880s.[7] He worked as a revenue collector as a young adult, using the position as a cover to carry out his protection racket.[8] His criminal record began with an assault in 1884 and progressed through extortion, arson, and menacing, and eventually to the kidnapping of the 19-year-old Baroness Clorinda Peritelli di Valpetrosa in June 1898,[9] for which he received a three-year sentence.[5][6][10]

Revolutionary mafioso

While incarcerated for attempted extortion, Cascio Ferro was recruited into the Fasci Siciliani (Sicilian Leagues), a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration, by Bernardino Verro, the president of the League in Corleone. The Leagues needed muscle in their social struggle of 1893–94.[11] Cascio Ferro became the president of the Fascio of Bisacquino.[4]

In January 1894, the Fasci were outlawed and brutally repressed on the orders of Prime Minister Francesco Crispi. Many leaders were put in jail; Cascio Ferro fled to Tunis for a year.[2][4][5] After serving his sentence for his role in the peasant unrest, Cascio Ferro returned to a position of social power and pressured authorities in Palermo to put him in charge of granting emigration permits in the district of Corleone.[11] According to Mafia historian Salvatore Lupo, Cascio Ferro was involved in clandestine emigration networks.[4]

In the United States

Sentenced for the kidnapping of the Baroness of Valpetrosa in 1898, Cascio Ferro was released in 1900. To escape special police surveillance in Sicily, he sailed to the United States and arrived in New York City at the end of September 1901. He lived for about 21⁄2 years in New York, acting as an importer of fruits and foods. He also spent six months in New Orleans.[6]

On 21 May 1902, Cascio Ferro was arrested in connection with a large counterfeiting operation in Hackensack, New Jersey. He was arrested at the barbershop of Giuseppe Romano on First Avenue, from which the counterfeit money had been distributed. Cascio Ferro managed to escape conviction—his alibi was that he worked at a paper mill—while the other gang members were tried and sentenced.[6]

In New York, he became associated with the Morello gang in Harlem, headed by Giuseppe Morello and Ignazio Lupo.[12] In September 1904, he returned to Sicily shortly after police sergeant Joseph Petrosino of the New York City Police Department ordered his arrest for involvement with the Barrel Murder; his application for American citizenship was consequently blocked.[6] Petrosino traced him to New Orleans, where Cascio Ferro had gone to escape detection, but he had already slipped away.[7]

Some observers consider Cascio Ferro as the one who brought the extortion practice of "continuing protection" in exchange for protection money (pizzo) from Sicily to the United States. "You have to skim the cream off the milk without breaking the bottle," he summarized the system. "Don't throw people into bankruptcy with ridiculous demands for money. Offer them protection instead, help them to make their business prosperous, and not only will they be happy to pay but they'll kiss your hands out of gratitude."[1]

Back in Sicily

Back in Sicily, Cascio Ferro rose to the position of a local notable. He was the capo elettore (ward heeler) of Domenico De Michele Ferrantelli, the mayor of Burgio and member of Parliament for the district of Bivona, as well as on good terms with the Baron Inglese.[4] He exercised influence over several Mafia cosche (clans) in the towns of Bisacquino, Burgio, Campofiorito, Chiusa Sclafani, Contessa Entellina, Corleone, and Villafranca Sicula, as well as some districts in the city of Palermo.[1][14]

A semi-factual and romantic portrait by journalist Luigi Barzini contributed much to form the legend of Don Vito:[1]

Don Vito brought the organization to its highest perfection without undue recourse to violence. The Mafia leader who scatters corpses all over the island in order to achieve his goal is considered as inept as the statesman who has to wage aggressive wars. Don Vito ruled and inspired fear mainly by the use of his great qualities and natural ascendancy. His awe-inspiring appearance helped him. … His manners were princely, his demeanour humble but majestic. He was loved by all. Being very generous by nature, he never refused a request for aid and dispensed millions in loans, gifts and general philanthropy. He would personally go out of his way to redress a wrong. When he started a journey, every major, dressed in his best clothes, awaited him at the entrance of his village, kissed his hands, and paid homage, as if he were a king. And he was a king of sorts: under his reign peace and order were observed, the Mafia peace, of course, which was not what the official law of the Kingdom of Italy would have imposed, but people did not stop to draw too fine a distinction.[15]

Police reports described Cascio Ferro as notoriously associated with the "high" Mafia, leading a life of luxury, going to the theater, cafés, gambling high sums at the Circolo dei Civili – a club for gentlemen, reserved for those with pretensions to education and elite status.[1]

The Petrosino murder

Cascio Ferro is considered to be the mastermind behind the murder of New York policeman and head of the Italian Squad, Joseph Petrosino, on 12 March 1909. He was shot and killed in Piazza Marina in Palermo; two men were seen running from the crime scene. Petrosino had gone to Sicily to gather information from local police files to help deport Italian gangsters from New York as illegal immigrants.[2][7][16][17] The two men were very much aware of the danger to each other's survival; Petrosino carried a note describing Cascio Ferro as “a terrible criminal”, while Cascio Ferro had a photograph of the police officer.[1]

Many accounts claim that Cascio Ferro personally killed Petrosino. Legend has it that Cascio Ferro excused himself from a dinner party among the high society at the home of his political patron De Michele Ferrantelli, took a carriage (that of his host according to some), and drove to Piazza Marina in Palermo's city centre. He and Petrosino engaged in a brief conversation, then Cascio Ferro killed Petrosino and returned to join the dinner again.[7][18] Historical reconstructions have dismissed this version and cannot locate Cascio Ferro at the scene of the crime.

News of the murder spread fast in U.S. newspapers and a swell of anti-Italian sentiment spread across New York.[19] Cascio Ferro pleaded his innocence and provided an alibi for the entire period when Petrosino was assassinated. He stayed in the house of De Michele Ferrantelli in Burgio.[16] However, the alibi provided by De Michele Ferrantelli was suspicious, taking into account the relation between the two. Moreover, while in jail after his arrest and life sentence in 1930, Cascio Ferro apparently claimed that he had killed Petrosino. According to writer Arrigo Petacco in his 1972 book on Joe Petrosino, Cascio Ferro said: "In my whole life I have killed only one person, and I did that disinterestedly … Petrosino was a brave adversary, and deserved better than a shameful death at the hands of some hired cut-throat."[20]

A report by Baldassare Ceola, the police commissioner of Palermo, concluded that the crime had probably been carried out by Mafiosi Carlo Costantino and Antonino Passananti under Cascio Ferro's direction.[19][21] Evidence was thin, however, and the case was effectively closed when in July 1911 the Palermo Court of Appeals discharged Cascio Ferro, as well as Costantino and Passananti, due to insufficient evidence to send them to trial.[16] Petrosino's murder was never solved.[17] Nevertheless, Costantino and Passananti were identified as the most likely assassins. Costantino died in the late 1930s and Passananti, in March 1969.[16][22]

In 2014, more than a century after the assassination, the Italian police overheard a tapped phone conversation in which a sibling claimed that Paolo Palazzotto had been the killer on the orders of Cascio Ferro. Palazzotto had been arrested after the shooting, but had been released for lack of evidence.[23][24][25] In a recorded conversation during an (unrelated) investigation by Italian police the suspected Mafia boss, Domenico Palazzotto, told other mafiosi that his great-uncle had killed Petrosino on behalf of Cascio Ferro.[26]

Downfall

In 1923, the sub-prefect of Corleone warned the Ministry of Interior that Cascio Ferro was "one of the worst offenders, quite capable of committing any crime." In May 1925, he was arrested as the instigator of a murder. He was able to be released on bail, as usual. However, with the rise of Fascism, his reputation and immunity were declining.[10]

In May 1926, Prefect Cesare Mori, under orders from Fascist leader Benito Mussolini to destroy the Mafia, arrested Cascio Ferro in a big round-up in the area that included Corleone and Bisacquino. More than 150 people were arrested. Cascio Ferro's godson asked the local landlord to intervene, but he refused: "Times have changed", was the reply.[27] He was indicted for participation in 20 murders, eight attempted murders, five robberies with violence, 37 acts of extortion, and 53 other offences including physical violence and threats.[28]

He was sentenced to life imprisonment on 27 June 1930, on the old murder charge.[10] He remained silent during the trial. Cascio Ferro had been arrested some 69 times before and always had been acquitted, but this time it was different. After hearing the sentence the president of the court asked Cascio Ferro if he had something to say in his defense. Cascio Ferro stood up and said: "Gentlemen, as you have been unable to obtain proof of any of the numerous crimes I have committed, you have been reduced to condemning me for the only one I never committed."[14][27][29] The "iron prefect", as Mori was known, wanted to give maximum publicity to the event. He had posters printed with pictures of Cascio Ferro and the text of the court sentence.[10]

Death and legacy

There is uncertainty about the exact date of his death. The most common account is that he died of natural causes in 1945 while serving his sentence at Ucciardone prison in Palermo.[14] Italian author Petacco found evidence for his 1972 book on Joe Petrosino that Cascio Ferro may have died of dehydration in the summer of 1943. According to Petacco, Cascio Ferro was left behind in his cell by prison guards while other inmates were evacuated in advance of the Allied invasion of Sicily.[30] However, according to historian Giuseppe Carlo Marino, Cascio Ferro was transferred to another prison in Pozzuoli in 1940, and the octogenarian was left to die during an Allied bombardment of that prison in 1943 (other sources mention 1942).[2][10] According to La Stampa, Cascio Ferro died on 20 September 1943, in the prison on the island of Procida.[31]

For years, a sentence believed to be carved by Cascio Ferro was legible on the wall of his Ucciardone cell: "Prison, sickness, and necessity, reveal the real heart of a man." Inmates considered occupying Don Vito's former cell a great honour.[7][32] Historians consider this account a legend rather than fact.[1]

Notes

- Servadio, Mafioso, pp. 57–63

- Marino, I Padrini, pp. 76-114

- Hess, Mafia & Mafiosi, p. 48

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, pp. 146–49

- (in Italian) Petacco, Joe Petrosino, p. 101-03

- Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, pp. 39-41

- The Murder of Joe Petrosino, The New York Press, November 19, 2002

- Biography of Vito Cascio Ferro on The American Mafia (Sources: "Petrosino Slayer may be in custody" April 7, 1909; "Told a story of Petrosino murder" December 29, 1912; "The origin of organized crime" by David Critchley; "The history of the Sicilian Mafia" by John Dickie)

- (in Italian) Il sequestro della baronessina Valpetroso, La Stampa, August 18, 1899

- (in Italian) Don Vito, da rivoluzionario a boss, La Sicilia, February 27, 2005

- Revolutionary Mafiosi: Voice and Exit in the 1890s, by John Alcorn, in: Paolo Viola & Titti Morello (eds.), L'associazionismo a Corleone: Un'inchiesta storica e sociologica (Istituto Gramsci Siciliano, Palermo, 2004)

- Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, p. 51

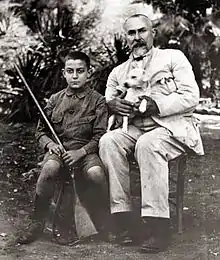

- Marino, Giuseppe Carlo (2006). "Photo pages". I Padrini (in Italian). Rome: Newton Compton Editori. ISBN 978-88-541-0570-6.

- Biography of Vito Cascio Ferro on GangRule.com (accessed October 16, 2010)

- Barzini, The Italians, p. 291

- Critchley, The Origin of Organized Crime in America, pp. 68-69

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, pp. 209-11

- For a romanticized version of Cascio Ferro's life, see The Sun King of The Mafia on Gangsters Inc.

- Lt. Petrosino Murder, GangRule.com (accessed October 16, 2010)

- Arlacchi, Mafia Business, p. 18

- Petrosino's Slayer May Be In Custody, The New York Times, April 7, 1909

- Dash, The First Family, p. 300

- (in Italian) Boss svela chi uccise Joe Petrosino, Ansa, June 23, 2014

- (in Italian) Colpo alla nuova Cupola: 91 arresti. Una cimice svela dopo 100 anni gli assassini di Joe Petrosino, La Repubblica, June 23, 2014

- Italy police 'solve' 1909 Petrosino Mafia murder, BBC News, June 23, 2014

- Italian police 'solve' suspected mafia killing of US detective in 1909, The Guardian, 23 June 2014

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 185-86

- Hess, Mafia & Mafiosi, p. 51

- Blood, Business, Honor, Time Magazine, October 15, 1984

- (in Italian) Petacco, Joe Petrosino, p. 207

- (in Italian) "Joe Petrosino ha offeso l'onore del padre mio", La Stampa, January 30, 1973

- Barzini, The Italians, p. 292

References

- Arlacchi, Pino (1988). Mafia Business. The Mafia ethic and the spirit of capitalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-285197-7

- Barzini, Luigi (1964/1968). The Italians, London: Penguin Books ISBN 0-14-014595-8 (originally published in 1964)

- Critchley, David (2009). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-99030-0

- Dash, Mike (2009). The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-1-4000-6722-0

- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet, ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Hess, Henner (1998). Mafia & Mafiosi: Origin, Power, and Myth, London: Hurst & Co Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-500-6

- Lupo, Salvatore (2009). The History of the Mafia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13134-6

- Marino, Giuseppe Carlo (2006). I Padrini. Rome: Newton Compton editore, ISBN 978-88-541-0570-6

- Petacco, Arrigo (1972/2001). Joe Petrosino: l'uomo che sfidò per primo la mafia italoamericana, Milan: Mondadori, ISBN 88-04-49390-9 (originally published in 1972)

- Reppetto, Thomas A. (2004). American Mafia: A History of Its Rise to Power. New York: Henry Holt & Co., ISBN 0-8050-7798-7

- Servadio, Gaia (1976). Mafioso. A history of the Mafia from its origins to the present day, London: Secker & Warburg ISBN 0-436-44700-2

- Michele Vaccaro, "Don Vito, l'<<l'anarco-mafioso>> dei Due Mondi", in Storia in Rete, luglio-agosto 2012, n. 81-82.

External links

- Joe Petrosino, a 20th Century Hero. A documented account of his assassination in Palermo, on view at the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, Queens College/CUNY (16 October - 2 December 2009)

- Biography of Vito Cascio Ferro on Gangrule

- Biography of Vito Cascio Ferro on The American Mafia