Vrana (military commander)

Vrana (d. 1458), historically known as Vrana Konti (literally, Count Vrana) was an Albanian military leader who was distinguished in the Albanian-Turkish Wars as one of the commanders of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, of whom he was one of the closest councillors. He probably belonged to the class of small lords who were tied to the Kastrioti family and possibly belonged to a common lineage (fis) with them. In his youth, he fought as a mercenary in the armies of Alfonso the Magnanimous. The term conte ("count") with which he became known in historical accounts didn't refer to an actual title he held, but to his status as a figure of importance.

.png.webp)

After his return to Albania, Vrana connected himself with Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg and participated in all of his major battles until his death in 1458. He is particularly praised for his resistance as the commander of the defense of Krujë during its first siege. He was offered a great deal of money and a high-ranking post in the Ottoman administration by Sultan Murad II in order to surrender the castle but he firmly held the defense with a maximum number of 4,000 troops against tens of thousands of Ottoman soldiers.

His son Bernardo left Albania when the Ottomans conquered the country and settled in the Kingdom of Naples and became duke of Ferrandina in 1505. His descendants, known as the Granai-Castriota held large estates in southern Italy and were distinguished in the internal and external affairs of the kingdom.

Life

As a result of the scarcity of primary sources, Brana's date of birth and his family have been a subject of debate. In early sources, he is usually referred to as Vrana and Vranaconte or Branaconte which correspond to the original patronymic surname of his descendants Branai in archival material. The literary form Uran is also observed in bibliography. There is no attested form of his surname. Vrana was probably one of those regional, small lords who were tied to the Kastrioti family - possibly via a common ancestral lineage - and were trusted by Kastrioti leaders.[1] This belonging to a common fis may have influenced the decision of his descendants to adopt the surname Castriota in addition to Granai.[2] In the folklore of the Albanians of Upper Reka, Vrana was from their region. In their stories, he is described as 2m (6'5ft) in height and a great warrior.[3] In his youth he fought in the armies of Alfonso the Magnanimous as a mercenary. The status of conte ("count") which is used to refer to him in contemporary historical accounts doesn't refer to an actual title with which he was bestowed but referred to his status as a man of importance.[4]

Military activity

Vrana had returned to Albania in the years prior to the beginning of the Albanian-Turkish wars under the leadership of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg in 1443. Vrana was one of his closest and most trusted allies. He may be the Urana who is mentioned in a document of Ottoman Krujë in relation to events as a result of which Skanderbeg was given direct control of the village of Mamurras.[5]

In the Albanian-Turkish wars, Krujë was the center of the Albanian war effort. The Ottomans besieged Krujë four times between 1450 and 1478, when it fell ten years after Skanderbeg's death. In May 1450, two years after the Ottomans had captured Svetigrad, they organized a mass campaign and laid siege to Krujë with an army numbering approximately 100,000 men and led again by Sultan Murad II himself and his son, Mehmed.[6] Christian volunteers from all over Europe had arrived in Krujë to assist the defense against the upcoming Ottoman siege - Slavs, Italians, Germans and others.[7] Skanderbeg left a protective garrison of 1,500 to 4,000 under Vrana in the town, while he harassed the Ottoman camps around Krujë by continuously attacking Sultan Murad II's supply caravans from Mount Tumenishta. Vrana had under his command several Germans, Italians, and Frenchmen, to whom he emphasized the importance of the siege and also ordered them to their positions.[8] Krujë had enough supplies for a sixteen-month siege. The women and children of Krujë were sent for protection to Venetian possessed areas, whereas the others were ordered to burn their crops and move into the mountains and fortresses.[6] Vrana addressed the army with encouraging speeches in order to raise morale, in Albanian and Italian, and through interpreters. The garrison repelled three major direct assaults on the city walls by the Ottomans, causing great losses to the besieging forces and forced the Ottomans to retreat. Ottoman attempts at finding and cutting the water sources failed, as did a sapped tunnel, which collapsed suddenly. An offer of 300,000 aspra (Turkish silver coins) and a promise of a high rank as an officer in the Ottoman army made to Vrana Konti, were both rejected by him.[9] Vrana's stance in the siege of Krujë is remembered in many folk songs and their variants in the region that Skanderbeg held.[10]

Vrana was one of the commanders in the Siege of Berat in 1455. The purpose of the siege was to recover the city of Berat for the Muzaka family and establish a firm stronghold for the League of Lezhë in southern Albania. Skanderbeg's army had 15,000 men including a 1,000 man strong Neapolitan contingent of siege warfare engineers which Alfonso had sent to deal with the fortification of the Berat Castle. The siege was at first successful and the fortifications were breached. An armistice was signed and the Albanian army expected that the Ottomans would surrender. Skanderbeg moved with a contingent to another area.[11] In mid July, however, the Ottomans sent an army of 20,000 troops led by Evrenosoglu Isa Bey, which surprised Skanderbeg's army. Only one commander, Vrana, managed to resist the initial Ottoman onslaught and pushed back several attacking waves. When Skanderbeg returned, the Ottoman relief force was repulsed and defeated. But the Albanians were exhausted and their numbers had dwindled to the point where the siege could not be continued. More than 5,000 of Skanderbeg's men died, including 800 men of the 1,000 Neapolitans.[12] The commander of the siege, Muzaka Thopia, was also killed during the conflict.[13]

Vrana died in 1458.[14] He died in the same year as Alfonso the Magnanimous and Pope Callixtus III who died on June 27 and on August 6, 1458 respectively. His death was a major blow to Skanderbeg who in a short period lost his most trusted commander Vrana and his most important political allies.[15] In the folklore of the Albanians of Upper Reka, Vrana is buried in that region with possible locations given near the village of Rimnica. In one of the variants of the story, when he returned to the village he was sick and disappointed by the possible outcome of the war. He climbed Skerteci, a mountain near Tanusha and gathered two large stone slabs which he told the villagers to use to make his tombstone.[3]

Historiography and literature

Historical accounts about Vrana's life and deeds are scarce beyond some references about him in official correspondence of the time and works which focus mainly on his role in the Albanian-Turkish Wars. Marin Barleti, who was a contemporary of Vrana, is one of the first authors who mention Vrana in his History of Scanderbeg in 1510. Paolo Giovio and Paolo Angelo examined Vrana's role in Gjergj Kastrioti's wars in their works in the first half of the 16th century. Giammaria Biemmi in his 1742 Istoria di Giorgio Castrioto some more details about his background - like a parental lineage to an Altisferi family which he links to the Zaharia family.[16] His work, which Biemmi claimed to be based on an unknown manuscript is considered a forgery in modern scholarship like many of his other works.[17]

In oral literature - epic poetry and tales - he is well-remembered for his involvement in the Skanderbeg's battles. Much of the corpus of these oral tales focus on the siege of Krujë. Geographically, in Albania these tales are found in an area from Krujë to the Kukës region in the north and the Upper Reka to the west. In written literature, Vrana inspired the character Vran in the epic poem Scanderbeide by Margherita Sarrocchi. The definitive edition of Scanderbeide was published in 1623. Among the Arbëreshe, the community of Albanian refugees that settled in Italy after Ottoman conquest, Vrana has been a particularly popular subject. In the 19th century, Gavril Dara the Younger in Kënga e Sprasme e Balës portrays Vrana with much affection as a high lord (zot i math).[18]

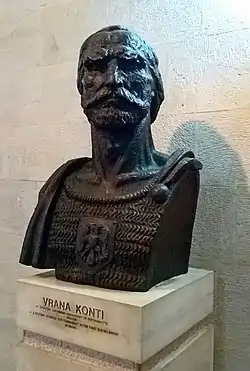

In 1967, a year dedicated to the memory of Scanderbeg in literature and visual arts in the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, a bust of Vrana was created by local sculptor from Krujë, Sabri Tuçi. In the same year, he was the subject of the painting Vrana Konti në kështjellën e Krujës (Vrana Konti in the fortress of Krujë) by Skender Kamberi.[19]

Descendants

His son, Bernardo took the surname Branai in Italy. His original name may also have been Vrana/Brana, which was italianized as Bernardo after his arrival in Italy. Gjon Muzaka wrote at the same time the Breve memoria de li discendenti de nostra casa Musachi, in which details emerge about Bernardo's family links to Albanian noble families through his marriage to Maria Zardari, daughter of Paul Zardari and a member of the Muzaka family. Muzaka's account and specifically its land claims are considered unreliable, but the link to Maria Zardari is confirmed in other works. Bernardo's son married a relative of Skanderbeg's wife, Donika Arianiti and their son Alfonso adopted the surname Castriota to honor that connection with the Kastrioti family with which their ancestor Vrana probably belonged to a common fis.[20][2] The surname Branai was altered to Granai, so the family became known as Castriota-Granai. Vrana may also have had another son who is recorded as a scribe Zaganos in Ottoman Krujë.[5]

The Granai-Castriota held large estates in the Kingdom of Naples and distinguished themselves in the internal and external affairs of the kingdom. They were part of the military feudal class and were loyalists of the Aragonese and the Spanish crown. Bernardo Branai became duke of Ferrandina for his services to Ferdinand the Catholic in 1505.[21] His son Alfonso further gained Mignano Monte Lungo and became governor of Terra d'Otranto and was a representative of the feudal nobility in the Imperial Cortes. To the family's assets were added the county of Copertino and the marquisate of Atripalda and other feudal grants. In this period, they began to add to their titles that of signori di Corinto and produced a copy of a document which purportedly proved that Manuel Palaiologos had granted to one of their ancestors Corinth as part of his "Albanian castles" in 1399. The document was a fabrication, typical of the land claims of the era.[22] The Granai wanted the fortress of Corinth because it was an important regional fortress and had been settled by Albanians in the Middle Ages. Antonio Granai in the 16th century consolidated and concentrated the family's holdings. He is the ancestor of all members (via patrilineal descent) of the Granai family today. In the chronicles of their era, the Granai of the Kingdom of Naples are remembered for their valor in the battlegrounds as condotierri. They were also patrons of art in southern Italy. Jacopo Sannazaro was very critical of the family, while Antonio de Ferraris dedicated two epistles to them.[21] The Granai kept their connections with Albania well into the 16th century. Alfonso Granai had an active spy network in Albania and maintained a force of local stradiots and his brother Giovanni (1468-1514), Duke of Ferrandina was known to have spoken Albanian. In 1551, a relative of the family in Albania, Dimitro Massi was part of an assembly in the cape of Rodon for the organization of anti-Ottoman revolt in the country.[20]

Sources

References

- Petta 2000, p. 9.

- Petta 2000, p. 61

- Dervishi 2014, p. 261

- Noli 1967, p. 105.

- İnalcık 1995, p. 76

- Francione 2006, p. 88

- Setton 1978, p. 101.

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 108.

- Babinger 1992, p. 60

- Sokoli 1984, p. 213.

- Noli 1967, p. 112.

- Francione 2006, p. 119

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 136.

- İnalcık 1995, p. 77.

- Rusha 1999, p. 18.

- Hodgkinson 1999, p. 227.

- Setton 1978, p. 73.

- Shuteriqi 1971, p. 366.

- Kondo 1967, p. 242.

- Malcolm 2015, p. 88

- Buono 2013, p. 200

- Petta 2000, p. 60.

Bibliography

- Buono, Benedict (2013). Satire, e Capitoli piacevoli (1549) con un'appendice di testi inediti di Bartolomeo Taegio (in Italian). Lampi di Stampa. ISBN 978-8848815543.

- Babinger, Franz (1992), Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01078-6

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1978). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume II: The Fifteenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-127-2.

- Francione, Gennaro (2006) [2003]. Aliaj, Donika (ed.). Skënderbeu, një hero modern: (Hero multimedial) [Skanderbeg, a modern hero)] (in Albanian). Translated by Tasim Aliaj. Tiranë, Albania: Shtëpia botuese "Naim Frashëri". ISBN 99927-38-75-8.

- Hodgkinson, Harry (1999), Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero, London: Centre for Albanian Studies, ISBN 978-1-873928-13-4

- İnalcık, Halil (1995), From empire to republic : essays on Ottoman and Turkish social history (in French), Istanbul: Isis Press, ISBN 978-975-428-080-7, OCLC 34985150

- Kondo, Ahmet (1967). "Krijimtaria letrare dhe artistike mbi temën e Skënderbeut - La création littéraire et artistique ayant comme thème Skanderbeg". Studime Historike. 4.

- Malcolm, Noel (2015). Agents of Empire: Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth-century Mediterranean World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190262785.

- Noli, Fan (1967). Biçoku, Kasem; Mele, Pandi; Gjiriti, Halil (eds.). Gjergj Kastrioti Skenderbeu: 1468-1968. Shtëpia botonjëse "Naim Frashëri".

- Petta, Paolo (2000). Despoti d'Epiro e principi di Macedonia: esuli albanesi nell'Italia del Rinascimento. Argo. ISBN 8882340287.

- Laporta, Alessandro (2004). La vita di Scanderbeg di Paolo Angelo (Venezia, 1539): un libro anonimo restituito al suo autore. Argo. ISBN 9788880865711.

- Dervishi, Nebi (2014). "Dëshmitë e Rekës Shqiptare pas regjistrimeve nëpër shekuj". In Pajaziti, Ali (ed.). Shqiptarët e Rekës së Epërme përballë sfidave të kohës [Albanians of Upper Reka in face of the challenges of time]. South East European University. ISBN 978-608-4503-95-8.

- Rusha, Spiro (1999). Shqipëria në vorbullat e historisë: studim historiko-politik [Albania throughout history: a socio-economic study]. Afërdita.

- Shuteriqi, Dhimitër (1971). Shuteriqi, Dhimitër (ed.). Historia e Letërsisë Shqipe. University of Pristina.

- Sokoli, Ramadan (1984). "The figure of Skanderbeg in folk songs". In Uçi, Alfred (ed.). Questions of Albanian Folklore. "8 Nëntori" Publishing House.