Vyacheslav Naumenko

Vyacheslav Grigoryevich Naumenko[lower-alpha 1] (25 February 1883 – 30 October 1979) was a Kuban Cossack leader and historian.

Vyacheslav Naumenko | |

|---|---|

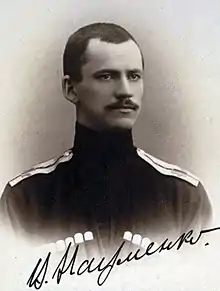

Naumenko in 1914 | |

| Native name | |

| Born | 25 February 1883 Petrovskaya, Kuban oblast, Russian Empire (now Krasnodar Krai, Russia) |

| Died | 30 October 1979 (aged 96) New York, New York, United States |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1900–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Battles/wars | |

| Notable work | Velikoye Predatelstvo (1962 and 1970) |

Cossack

Naumenko was born in Petrovskaya, Kuban Oblast near the Black Sea in the territory of the Kuban Host. Pursuing a military career, he graduated from the Voronezh Mikhailovsky Cadet Corps in 1900, the Nicholas Calvary School in 1903, and from the Military Academy of the General Staff in 1914.[1] He entered the First World War with the rank of voiskovi starshina (lieutenant colonel), serving as chief of staff of the 1st Kuban Cossack Calvary Division.[1] He subsequently served as chief of staff of the 4th Kuban Division from August 1914 to January 1917 and as chief of staff of the Cossack field forces from January 1917 – January 1918.[2]

On 30 August 1914, he was wounded in action while fighting against the Austrians in the city of Stryi in Galicia (which belonged to the Austrian empire at the time) and he was awarded the 4th class Order of Saint Anna on 15 December 1914 for heroism under fire. On 7 February 1915, he was awarded the 3rd class Order of Saint Anna for an action in the Carpathians on 25 September 1914 against the Austrians. On 6 March 1915, he was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir for the same action at Stryi where as he continued to fight on despite being wounded. On 6 April 1915, he was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislaus for heroism under fire while fighting the Austrians on 16–17 September 1914.

Like almost all Russian officers, Naumenko accepted the February Revolution of 1917 and the downfall of the ancient House of Romanov. The Cossack Hosts, who enjoyed a privileged position under the empire, tended to see themselves as bound by personal loyalty to the emperor rather than serving Russia, and with the end of the monarchy, many Cossacks took the viewpoint that their loyalty to Russia had ended. Naumenko served the Provisional government and on 14 August 1917 he was appointed a senior adjunct to the quartermaster of the Special Army. Like many officers, Naumenko was worried about the increasing signs of social breakdown over the course of 1917 and by the end of the year had grown close to General Lavr Kornilov, a Eurasian Siberian Cossack (Kornilov's mother was a Buryat). Kornilov who was well known for being described as having "the heart of a lion but the brain of a sheep" was a right-wing officer who was the first to raise his banner against the Bolsheviks following the October Revolution.[3]

Russian Civil War

In the Russian Civil War, Naumenko fought on the White side. The British journalist Christopher Booker called Naumenko "a White Russian hero during the Civil War".[4] Naumenko took part in the Ice March of the Volunteer Army under Kornilov in February–March 1918.[2] On 18 February 1918, he was promoted to the rank of full colonel.[1] By early March 1918, Naumenko was leading the Cossacks of the Kuban People's Republic into sporadic, but bitter clashes against the Red Army.[5] Later in March 1918, Naumenko led the first joint operation between the Whites and the Kuban Host to take the stanitsa Novo-Dmitrievakain from the Bolsheviks.[6] From April–June 1918, he served as chief of staff to a cavalry brigade commanded by General Viktor Pokrovsky active in southern Russia.[2] On 27 June 1918, he took command of the 1st Kuban Mounted Regiment, and on 14 August 1918 he was promoted to take command of the 1st Mounted Brigade.[2] On 19 November 1918, he assumed command of the 1st Mounted Division.[2] On 8 December 1918, he was promoted to major general.[1]

On 15 December 1918, he was elected a field ataman of the Kuban Host, serving as their "minister of war".[7] On 14 February 1919, the Kuban ataman Alexander Filimonov issued a degree putting all of the Cossacks of the Kuban Host under the command of Naumenko.[8] The same order also declared the Kuban Host was not to take orders from the White generals.[9] However, Naumenko was against Cossack separatism, and favored having the Kuban Host accept the authority of the White leaders instead of operating alone as the separatists favored.[10] Relations between the rada (council) and Naumenko were strained and he was forced to resign on 14 September 1919.[10] Naumenko served in the reserves of the Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR) from 14 September 1919 to 11 October 1919, when he took command of the 2nd Kuban Corps, which he held until March 1920.[2] In March 1920, following the defeat of the AFSR, Naumenko fled down the Black Sea coast into Georgia.[2]

In April 1920, he and what was left of his forces sailed across the Black Sea to join the main White Army in the Crimea under the command of General Baron Pyotr Wrangel, known to the Soviets as the "Black Baron".[2] The Crimea was connected to the mainland via the very narrow Isthmus of Perekop, which proved to be both a blessing and a curse for Wrangel; the narrowness of the isthmus limited the path of any army trying to break in or out of the Crimea, making it hard for both the Red Army to break into the Crimea and for the White Army to break out. In July 1920, as part of Wrangel's attempt to break out of the Crimea, Naumenko was landed on the coast of the Kuban with the aim of distracting the Red Army, but by August 1920 Naumenko had been defeated and was forced to evacuate to the Crimea.[2] From 9 September 1920 to 3 October 1920, Naumenko commanded the 1st Cavalry Division.[2] At the same time, he was promoted to lieutenant general.[1] On 3 October 1920, Naumenko was badly wounded in action and therefore was confined to a hospital to recover from his wounds.[2] Between 7–17 November 1920, the Battle of Perekop saw the Red Army finally break through the White lines on the Isthmus of Perekop. Following the final defeat of the Whites in the Crimea, Naumenko was evacuated together with what was left of the White Army on 18 November 1918.[2] A British ship picked up Naumenko and took him and his men to Constantinople, and from there to on the isle of Lemnos.[2]

First exile

He went into exile in 1920 following the final defeat of the White Army in the Crimea and was elected ataman of the Kuban Host on the Greek island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea.[11] Naumenko was still serving as the ataman of the Kuban Host at the time of his death in 1979, setting a record for longevity as no other ataman ever held office for so long.[2] The responsibility of the refugees on Lemnos rested with the French government, which had extended a limited diplomatic recognition to the White movement as the British government refused to pay for any of the costs of housing and feeding them.[12] The British prime minister David Lloyd George never lost the hope of reaching a settlement with Vladimir Lenin and saw Wrangel as an obstructionist.[12] The refugee camp on Lemnos was created as there was insufficient space for the refugees in Constantinople, a city that was under Allied occupation in the years 1918–1923, and there were fears of an epidemic breaking out owing to poor sanitation in the refugee camps around Constantinople.[12]

Wrangel wanted to keep his defeated army together to resume the civil war at the first opportune moment while the French General Broussaud in charge of the camp wanted to see the refugees settled as soon as possible in order to end the burden on the French treasury, making for difficult relations.[12] The Soviet government indicated a willingness to offer an amnesty and to allow the Kuban Cossacks to return, an offer that Brossaud was in favor of accepting while Wrangel and the rest of Cossack leaders were opposed to.[12] Brossaud often quarreled with Naumenko and in his reports to Paris portrayed him as a trouble-maker.[12] In April 1921, Broussaud forbade Naumenko to return to Lemnos after he went on a trip to Constantinople.[12]

At a meeting in Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey) in 1921, Naumenko met with the atamans of the Don and Terek Hosts which led to the establishment of the United Council of the Don, Kuban and Terek Hosts to manage the affairs of the Cossacks in exile.[13] Subsequently, he settled in Belgrade, Yugoslavia where the Russophile King Alexander was very welcoming to Russian emigres. In October 1921, the Lemonos refugee camp was shut down with some of the Kuban Host choosing to return to Soviet Russia where an amnesty was promised for them while those who wished to stay in exile went to either Bulgaria or Yugoslavia.[12] Naumenko was active in trying to preserve the Russian heritage of the emigres, setting up schools to discourage assimilation and encourage the children of the emigres to speak Russian instead of Serbo-Croatian.[13] In Belgrade, Naumenko founded the Museum of the Cossacks to encourage the children of the Cossack emigres to remember their heritage. In exile, Naumenko published several books in Russian about the Civil War.[14]

World War II

After Operation Barbarossa started on 22 June 1941, Naumenko declared his willingness to serve Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union.[15] As the ataman of the Kuban Host, Naumenko was active in using his prestige to recruit Cossacks to fight for Germany.[16] In March 1942, German policy towards Soviet POWs changed as the previous policy of letting the POWs starve to death was ended and henceforward it was German policy to encourage the POWs to fight for Germany. Starting in the spring of 1942, Naumenko toured the POW camps urging Cossack POWs to enlist in the Wehrmacht.[17]

By the time of the Second World War, Naumenko had changed his opinion about Cossack separatism due to the influence of Alfred Rosenberg, and in 1942 publicly praised the plans unveiled in Berlin for a Nazi puppet state to be called Cossackia.[16] In December 1942, Naumenko raised a regiment for the Russian Protective Corps serving in Serbia. Starting in April 1943, all of the Cossacks formations in the Wehrmacht were concentrated in Mielau (modern Mława, Poland) to form the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division of the Wehrmacht. When the men of the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division learned in September 1943 that they would not be going to the Eastern Front as expected and were instead being sent to the Balkans largely because Adolf Hitler distrusted their loyalty to the Reich, the divisions's commander General Helmuth von Pannwitz had Naumenko together with the former Don Host ataman Pyotr Krasnov give speeches before the Cossacks at their Mielau base.[18] Both Krasnov and Naumenko told the assembled Cossacks that they would still be fighting the "international Communist conspiracy" in the Balkans and promised that they would ultimately go to fight on the Eastern Front.[18] In January 1944, Naumenko left his home in Belgrade and reviewed while wearing the traditional black uniform of the Kuban Host the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division serving in Bosnia and Croatia, which he then praised in a speech.[18]

During this period, Naumenko together with Pyotr Krasnov and Andrei Shkuro was one of the leaders of the Cossack "government-in-exile" created by Alfred Rosenberg.[19] The Cossack "government-in-exile" was created in Berlin on 31 March 1944 headed by Krasnov who appointed Naumenko his "minister of war".[20] When Krasnov was out of Berlin, Naumenko served as the acting director of the Main Directorate of Cossack Forces.[2] Naumenko lived in Berlin from March 1944 onward, but in February 1945 left the threatened German capital as the Red Army had advanced to within 60 miles of Berlin.[21] In 1945 Naumenko surrendered to the Americans rather than the British, which almost certainly saved his life as the Americans were less strict about repatriating Cossacks to the Soviet Union.[21] Together with his son-in-law, the Don Cossack Nikolai Nazarenko, Naumenko surrendered to the Americans in Munich in April 1945.[22] Krasnov and Shkuro surrendered to the British who repatriated them to the Soviets in May 1945. In 1947 both Krasnov and Shkuro were hanged in Moscow following their convictions on charges of war crimes.

Second exile

Naumenko settled in New York, where he published a two-volume book in 1962 and 1970 about the Repatriation of Cossacks entitled Velikoe Predatelstvo (The Great Betrayal).[23] He was greatly embittered against Britain for the 1945 repatriation, and the matter was something of an obsession for him.[2] Naumenko spent much time during his second exile visiting Australia, which took in a substantial number of Cossack refugees after 1945.[24] The Austrian-born American author Julius Epstein described Naumenko in the early 1970s as living in a modest house in New York together with his daughter and son-in-law Nazarenko.[25] He assisted the historian Count Nikolai Tolstoy with his books Victims of Yalta and his controversial book The Minister and the Massacres. Naumenko spent his last days in a nursing home run by the Tolstoy Foundation in New York city, where he suffered from senility.[2][26] The two volumes of Velikoe Predatelstvo were translated into English by the American novelist William Dritschilo under the title The Great Betrayal in 2015 and 2018.

Works in English

- The Great Betrayal Volume I, translated by William Dritschilo, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, California, 2015 ISBN 1511524170

- .The Great Betrayal Volume II, translated by William Dritschilo, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, California, 2018, ISBN 1986932354

Books and articles

- Booker, Christoper (1997). A Looking-glass Tragedy: The Controversy Over the Repatriations from Austria in 1945. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0715627384.

- Burgh, Hugo de (2008). Investigative Journalism. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1134068708.

- Bagni, Bruno (March 2009). "Lemnos, l'île aux Cosaques". Cahiers du Monde Russe. 50 (1): 187–230.

- Cha-jŏng, Ku (2009). Cossack Modernity: Nation Building in Kubanʹ, 1917-1920. Berkeley: University of California.

- Epstein, Julius (1973). Operation Keelhaul; The Story of Forced Repatriation from 1944 to the Present. New York: Devin-Adair Publishing Company. ISBN 0815964072.

- Groushko, Michael (1992). Cossacks: Warrior Riders of the Steppes. New York: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0806987030.

- Kenez, Peter (1971). Civil War in South Russia, 1918: The First Year of the Volunteer Army. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0520017099.

- Kenez, Peter (1977). Civil War in South Russia, 1919-1920: The Defeat of the Whites. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0520367995.

- Longworth, Philip (1970). The Cossacks. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Mather, Carol (1992). Aftermath of War: Everyone Must Go Home. London: Brassey's. ISBN 0080377084.

- McCauley, Martin (1997). Who's who in Russia Since 1900. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 0415138973.

- Mueggenberg, Brent (2019). The Cossack Struggle Against Communism, 1917-1945. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-1476679488.

- Newland, Samuel J. (1991). The Cossacks in the German Army 1941-1945. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0714681997.

- Persian, Jayne (July 2018). "Cossack Identities: From Russian Émigrés and Anti-Soviet Collaborators to Displaced Persons". Journal Immigrants & Minorities. 36 (2): 125–142. doi:10.1080/02619288.2018.1471856. S2CID 150349528.

- Procyk, Anna (1995). Russian Nationalism and Ukraine: The Nationality Policy of the Volunteer Army During the Civil War. Kiev: CIUS Press. ISBN 1895571049.

- Smele, Jonathan D. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Latham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442252813.

- Thomas, Nigel (2015). Hitler's Russian & Cossack Allies 1941–45. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1472806871.

Notes

References

- Smele 2015, p. 782.

- Smele 2015, p. 783.

- McCauley 1997, p. 119.

- Booker 1997, p. 314.

- Cha-jŏng 2009, p. 219.

- Cha-jŏng 2009, p. 221.

- Kenez 1971, p. 180.

- Kenez 1977, p. 117.

- Cha-jŏng 2009, p. 273.

- Kenez 1977, p. 118.

- Longworth 1970, p. 315.

- Bagni, Bruno (March 2009). "Lemnos, l'île aux Cosaques". Cahiers du Monde Russe. 50 (1): 187–230. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Mueggenberg 2019, p. 177.

- Procyk 1995, p. 57.

- Groushko 1992, p. 134.

- Longworth 1970, p. 330.

- Thomas 2015, p. 22.

- Newland 1991, p. 155.

- Mather 1992, p. 236.

- Newland 1991, p. 141.

- Mather 1992, p. 238.

- Newland 1991, p. 176.

- Burgh 2008, p. 243.

- Persian 2018, p. 132.

- Epstein 1973, p. 80.

- Newland 1991, p. 188.