Warrant officer

Warrant officer (WO) is a rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned officer ranks, the most senior of the non-commissioned officer (NCO) ranks, or in a separate category of their own. Warrant officer ranks are especially prominent in the militaries of Commonwealth nations and the United States.

The name of the rank originated in medieval England. It was first used during the 13th century, in the Royal Navy, where warrant officers achieved the designation by virtue of their accrued experience or seniority, and technically held the rank by a warrant, rather than by a formal commission (as in the case of a commissioned officer). Nevertheless, WOs in the British services have traditionally been considered and treated as distinct from non-commissioned officers.

Warrant officers in the United States are classified in rank category "W", which is distinct from "O" (commissioned officers) and "E" (enlisted personnel). However, chief warrant officers are officially commissioned, on the same basis as commissioned officers, and take the same oath. US WOs are usually experts in a particular technical field, with long service as enlisted personnel; in some cases, however, direct entrants may become WOs—for example, individuals completing helicopter pilot training in the US Army Aviation Branch become flight warrant officers immediately.

In Commonwealth countries, warrant officers have usually been included alongside NCOs and enlisted personnel in a category called other ranks (ORs), which is equivalent to the US "E" category (i.e. there is no separate "W" category in these particular services). In Commonwealth services, warrant officers rank between chief petty officer and sub-lieutenant in the navy, between staff sergeant and second lieutenant in the army, and between flight sergeant and pilot officer in the air force.

Origins

The warrant officer corps began in the nascent Royal Navy,[1] which dates its founding to 1546. At that time, noblemen with military experience took command of the new navy, adopting the military ranks of lieutenant and captain. These officers often had no knowledge of life on board a ship—let alone how to navigate such a vessel—and relied on the expertise of the ship's master and other seamen who tended to the technical aspects of running the ship. As cannon came into use, the officers also required gunnery experts; specialist gunners began to appear in the 16th century and also had warrant officer status.[2] Literacy was one thing that most warrant officers had in common, and this distinguished them from the common seamen: according to the Admiralty regulations, "no person shall be appointed to any station in which he is to have charge of stores, unless he can read and write, and is sufficiently skilled in arithmetic to keep an account of them correctly". Since all warrant officers had responsibility for stores, this was enough to debar the illiterate.[3]

Rank and status in the 18th century

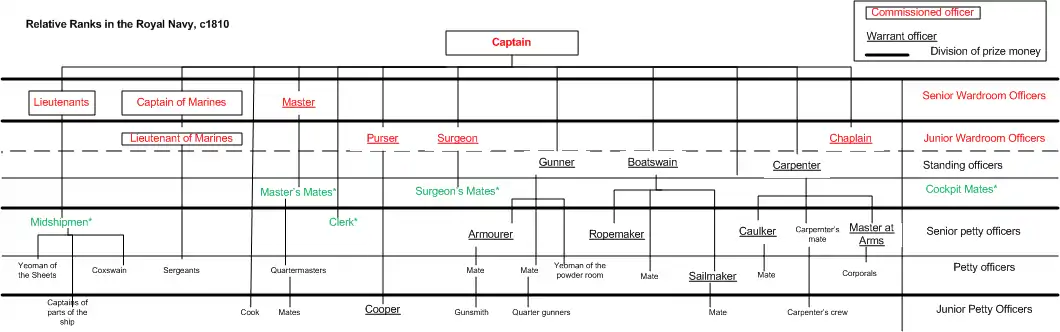

In origin, warrant officers were specialist professionals whose expertise and authority demanded formal recognition.[3] In the 18th century they fell into two clear categories: on the one hand, those privileged to share with the commissioned officers in the wardroom and on the quarterdeck; and on the other, those who ranked with more junior members of the ship's crew.[4] Somewhere between the two, however, were the standing officers, notable because, unlike the rest of the ship's company, they remained with the ship even when it was out of commission (e.g. for repair, refitting or replenishment, or whilst laid up); in these circumstances they were under the pay and supervision of the Royal Dockyard.

Wardroom warrant officers

These classes of warrant officer messed in the wardroom with the commissioned officers:

- the master: the senior warrant officer, a qualified navigator and experienced seaman who set the sails, maintained the ship's log and advised the captain on the seaworthiness of the ship and crew;

- the surgeon: who treated the sick and injured and advised the captain on matters of health;

- the purser: responsible for supplies, food and pay for the crew.

In the early 19th century, they were joined in the wardroom by naval chaplains, who also had warrant officer status (though they were only usually present on larger vessels).

Standing warrant officers

The standing officers were:[4]

Junior warrant officers

Other warrant officers included surgeon's mates, boatswain's mates and carpenter's mates, sailmakers, armourers, schoolmasters (involved in the education of boys, midshipmen and others aboard ship) and clerks. Masters-at-arms, who had formerly overseen small-arms provision on board, had by this time taken on responsibility for discipline.

Warrant officers in context

By the end of the century, the rank structure could be illustrated as follows (the warrant officers are underlined):

Demise of the royal naval warrants

In 1843, the wardroom warrant officers were given commissioned status, while in 1853 the lower-grade warrant officers were absorbed into the new rate of chief petty officer, both classes thereby ceasing to be warrant officers. On 25 July 1864 the standing warrant officers were divided into two grades: warrant officers and chief warrant officers (or "commissioned warrant officers", a phrase that was replaced in 1920 with "commissioned officers promoted from warrant rank", although they were still usually referred to as "commissioned warrant officers", even in official documents).

By the time of the First World War, their ranks had been expanded with the adoption of modern technology in the Royal Navy to include telegraphists, electricians, shipwrights, artificer engineers, etc. Both warrant officers and commissioned warrant officers messed in the warrant officers' mess rather than the wardroom (although in ships too small to have a warrant officers' mess, they did mess in the wardroom). Warrant officers and commissioned warrant officers also carried swords, were saluted by ratings, and ranked between sub-lieutenants and midshipmen.[2]

In 1949, the ranks of warrant officer and commissioned warrant officer were changed to "commissioned officer" and "senior commissioned officer", the latter ranking with but after the rank of lieutenant, and they were admitted to the wardroom, the warrant officers' messes closing down. Collectively, these officers were known as "branch officers", being retitled "special duties" officers in 1956. In 1998, the special duties list was merged with the general list of officers in the Royal Navy, all officers now having the same opportunity to reach the highest commissioned ranks.[2]

Modern usage

Australia

The Royal Australian Navy rank of warrant officer (WO) is the Navy's only rank appointed by warrant and is equivalent to the Army's WO1, and the RAAF's warrant officer. The most senior non-commissioned member of the Navy is the Warrant Officer of the Navy (WO-N), an appointment that is only held by one person at a time.[6]

The Australian Army has two warrant officer ranks: warrant officer class two (WO2) and warrant officer class one (WO1), the latter being senior in rank. The equivalent rank of WO2 in the Navy is now chief petty officer, and the RAAF equivalent of the Army's WO2 is now flight sergeant, although in the past there were no equivalents. All warrant officers are addressed as "sir" or "ma'am" by subordinates. To gain the attention of a particular warrant officer in a group, they can be addressed as "Warrant Officer Bloggs, sir/ma'am" or by their appointment, e.g. "ASM Bloggs, sir/ma'am". Some warrant officers hold an appointment such as company sergeant major (WO2) or regimental sergeant major (WO1). The warrant officer appointed to the position of Regimental Sergeant Major of the Army (RSM-A) is the most senior enlisted soldier in the Australian Army and differs from other Army warrant officers in that their rank is just warrant officer (WO). The appointment of RSM-A was introduced in 1983. The rank insignia are: a crown for a WO2 (or a crown in a square on AMCU (camouflage uniform) rank slides); the Australian Commonwealth Coat of Arms (changed from the Royal Coat of Arms in 1976) for a WO1; and the Australian Commonwealth Coat of Arms surrounded by a laurel wreath for the RSM-A.[7][6]

The Royal Australian Air Force rank of warrant officer (WOFF) is the RAAF's only rank appointed by warrant and is equivalent to both the Army's WO1 and the Navy's WO. The most senior non-commissioned member of the RAAF is the Warrant Officer of the Air Force (WOFF-AF), an appointment that is only held by one person at a time.[6]

| Navy | Army | Air Force | |

| Insignia |  |

|

|

| Title | Warrant officer | Warrant officer class 1 | Warrant officer |

| Abbreviation | WO | WO1 | WOFF |

Bangladesh

- Rank insignia

Master Chief Petty Officer

Master Chief Petty Officer Master Warrant Officer

Master Warrant Officer Master warrant officer

Master warrant officer

Warrant officer is the lowest junior commissioned officer rank in the Bangladesh Army[8] and Bangladesh Air Force,[9] ranking below senior warrant officer and master warrant officer.

Canada

In the Canadian Army and Royal Canadian Air Force, the cadre of warrant officers includes the specific ranks of warrant officer (adjudant in French), master warrant officer (adjudant-maître), and chief warrant officer (adjudant-chef). Before unification in 1968, there were two ranks of warrant officer (WO2 and WO1) in the Canadian Army and RCAF that followed the British structure.

- Rank insignia

Insignia of a chief warrant officer

Insignia of a chief warrant officer Insignia of a master warrant officer

Insignia of a master warrant officer Insignia of a warrant officer

Insignia of a warrant officer

India

Junior commissioned officers are the Indian Armed Forces equivalent of warrant officer ranks. Those in the Indian Air Force actually use the ranks of junior warrant officer, warrant officer and master warrant officer.

In the British Indian Army, warrant officer ranks existed but were restricted to British personnel, mostly in specialist appointments such as conductor and sub-conductor. Unlike in the British Army, although these appointments were warranted, the appointment and rank continued to be the same and the actual rank of warrant officer was never created. Indian equivalents were viceroy's commissioned officers.

| Junior commissioned officers[10] | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Master warrant officer | Warrant officer | Junior warrant officer |

Irish Naval Service

| Equivalent NATO Code | OR-9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Ireland |

Executive |

Administrative |

Engineering |

Communications |

| Irish | Oifigeach Barántais | |||

| English | Warrant officer | |||

Malaysia

In the Malaysian Armed Forces, warrant officers (Malay: pegawai Waran) are the highest ranks for non commissioned officers.

| Rank group | Warrant officers | |

|---|---|---|

| Pegawai waran I | Pegawai waran II | |

|

| |

| Pegawai waran I | Pegawai waran II | |

| Pegawai waran udara I | Pegawai waran udara II | |

| English | Warrant officer class I | Warrant officer class II |

New Zealand

The New Zealand Army usage is the same as the Australian Army, having two ranks. The warrant officer class 2 (WO2), addressed as "sergeant major", and the warrant officer class 1 (WO1), addressed as "sir" or "ma'am". There are also appointments such as company and squadron sergeant major (CSM and SSM) which are usually WO2 positions and regimental sergeant major (RSM), which are usually WO1 positions. The highest ranking WO1 holds the position of Sergeant Major of the Army (SMA). In certain uniforms, WO2s wear black shoes, the same as the enlisted ranks, whilst WO1s wear brown shoes, in common with commissioned officers. The exception to this are WO1s of the Royal New Zealand Armoured Corps (RNZAC), who wear black shoes.

The Royal New Zealand Navy has a single warrant officer rank, addressed as "sir" or "ma'am". This rank is equivalent to the Army WO1.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force also has a single warrant officer rank, equivalent to the Navy warrant officer, and the Army warrant officer class 1 (WO1). A warrant officer in the RNZAF is addressed as "sir" or "ma'am". Previously an aircrew warrant officer was known as master aircrew; however this rank and designation is no longer used. The RNZAF also has a post of Warrant Officer of the Air Force, the most senior warrant officer position in the RNZAF.

Boys' Brigade

The rank of warrant officer is the highest rank a Boys' Brigade boy can attain in secondary school.

National Civil Defence Cadet Corps

The rank of warrant officer is given to selected non-commissioned officers in National Civil Defence Cadet Corps units. It is above the rank of staff sergeant, and below the rank of cadet lieutenant.[13] It is the highest rank a cadet can attain in the NCDCC while they are in secondary school. The rank insignia is one point-up chevron, a Singapore coat of arms, and a garland below.

Singapore Armed Forces

In the Singapore Armed Forces, warrant officers begin as third warrant officers (3WO), previously starting at the rank of second warrant officer, abbreviated differently as WO2 instead. This rank is given to former specialists who have attained the rank of master sergeant and have either gone through, or are about to go through the Warfighter Course at the Specialist and Warrant Officer Advanced School (SWAS) in the Specialist and Warrant Officer Institute (SWI). In order to be promoted to a second warrant officer (2WO) and above, they must have been selected for and graduated from the joint warrant officer course at the SAFWOS Leadership School.[14] Warrant officers rank between specialists and commissioned officers. They ordinarily serve as battalion or brigade regimental sergeant majors. Many of them serve as instructors and subject-matter experts in various training establishments. Warrant officers are also seen on the various staffs headed by the respective specialist officers. There are six grades of warrant officer (3WO, 2WO, 1WO, MWO, SWO and CWO).

Warrant officers used to have their own mess. For smaller camps, this mess is combined with the officers' mess. Warrant officers have similar responsibilities to commissioned officers.

Warrant officers are usually addressed as "encik" ("mister" in Malay language) or as "warrant (surname)" or "encik" (surname).[14] Exceptions to this are those who hold appointments. Warrant officers holding the appointment such as commanding officer (CO) and officer commanding (OC) are to be addressed as "sir" by other ranks, and those holding sergeant major appointments such as regimental sergeant major (RSM), company sergeant major (CSM), formation sergeant major (FSM), institute sergeant major (ISM) and the Sergeant Major of the Army (SMA) are to be addressed as "sergeant major" by other ranks. Also, all warrant officers holding the rank of chief warrant officer (CWO) are to be addressed as "sir" by other ranks. Since all warrant officers are non-commissioned officers, they are not saluted.

Although ceremonial swords are usually reserved for commissioned officers, warrant officers of the rank of master warrant officer (MWO) and above are presented with ceremonial swords, but continue to carry the pace stick, with the sword sheathed during drills and parades.

Singapore Civil Defence Force

In the Singapore Civil Defence Force, there are two warrant officer ranks. These ranks are (in order of ascending seniority) warrant officer (1) and warrant officer (2).[15] Previously, before the Home Team Unified Rank Scheme was introduced, there were two additional ranks of warrant officer, namely senior warrant officer (1) and senior warrant officer (2). Both ranks are now obsolete, although existing holders of these ranks were allowed to keep their rank.

South Africa

In the South African National Defence Force, a warrant officer (WO) is set apart from those who hold a non-commissioned officer (NCO) rank. Warrant officers hold a warrant of appointment endorsed by the Minister of Defence. Warrant officers hold very specific powers, which are set out in the Defence Act and the Military Defence Supplementary Measures Act. Before 2008, there were two classes – warrant officer class 1 and 2. A warrant officer class 1 could be appointed to positions such as regimental sergeant major, formation sergeant major or Sergeant Major of the Army or Warrant Officer of the Navy. In 2008, five new warrant officer ranks were introduced above warrant officer class 1: senior warrant officer (SWO), master warrant officer (MWO), chief warrant officer (CWO), senior chief warrant officer (SCWO) and master chief warrant officer (MCWO).[16]

| Rank group | Warrant officer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

National Defence Force |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Master chief warrant officer | Senior chief warrant officer | Chief warrant officer | Master warrant officer | Senior warrant officer | Warrant officer class 1 | Warrant officer class 2 | |

United Kingdom

Royal Navy

In 1973, warrant officers reappeared in the Royal Navy, but these appointments followed the army model, with the new warrant officers being ratings rather than officers. They were initially known as fleet chief petty officers (FCPOs), but were renamed warrant officers in the 1980s. They rank with warrant officers class one in the British Army and Royal Marines and with warrant officers in the Royal Air Force.[2]

There are executive warrant officers for commands and ships.[17] Five branches (surface ships, submarines, Royal Marines, Fleet Air Arm, and Maritime Reserves) each have a command warrant officer.[18] The senior RN WO is the Warrant Officer of the Royal Navy.[19][20] Under the Navy Command Transformation Programme, there are now a Fleet Commander's Warrant Officer and a Second Sea Lord's Warrant Officer, all working with the Warrant Officer of the Naval Service, taking over the roles of the Command Warrant Officers.[21][22][23]

In 2004, the rank of warrant officer class 2 was introduced. However, the rank was phased out in April 2014,[24] but is being reinstated for non-technical and technical branches of the Royal Navy in 2021.[25]

British Army

In the British Army, there are two warrant ranks, warrant officer class two (WO2) and warrant officer class one (WO1), the latter being the senior of the two. These ranks were previously abbreviated as WOII and WOI (using Roman instead of Indo-Arabic numerals). "Warrant officer first class" or "second class" is incorrect. The rank immediately below WO2 is staff sergeant (or colour sergeant).[2] From 1938 to 1940 there was a WOIII platoon sergeant major rank.[26]

In March 2015, the new appointment of Army Sergeant Major was created, though the holder is not in fact a warrant officer but a commissioned officer holding the rank of captain.[27][28] The creation of the appointment of command sergeant major was announced in 2009.[29]

Royal Marines

Before 1879, the Royal Marines had no warrant officers:[30] by the end of 1881, the Royal Marines had given warrant rank to their sergeant-majors and some other senior non-commissioned officers, in a similar fashion to the army.[31] When the army introduced the ranks of warrant officer class I and class II in 1915, the Royal Marines did the same shortly after.[32] From February 1920, Royal Marines warrant officers class I (renamed warrant officers) were given the same status as Royal Navy warrant officers and the rank of warrant officer class II was abolished in the Royal Marines, with no further promotions to this rank.[33]

The marines had introduced warrant officers equivalent in status to the Royal Navy's from 1910 with the Royal Marines gunner (originally titled gunnery sergeant-major), equivalent to the navy's warrant rank of gunner.[34][35] Development of these ranks closely paralleled that of their naval counterparts: as in the Royal Navy, by the Second World War there were warrant officers and commissioned warrant officers (e.g. staff sergeant majors, commissioned staff sergeant majors, Royal Marines gunners, commissioned Royal Marines gunners, etc.). As officers, they were saluted by junior ranks in the Royal Marines and the army. These all became (commissioned) branch officer ranks in 1949, and special duties officer ranks in 1956. These ranks would return in 1972, this time similar to their army counterparts, and not as the RN did before. The most senior Royal Marines warrant officer is the Corps Regimental Sergeant Major. Unlike the RN proper (since 2014), it retains both WO ranks.

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force first used the ranks of sergeant major first and second class as inherited from the Royal Flying Corps, with the rank badges of the Royal coat of arms and the crown respectively. In the 1930s, these ranks were renamed warrant officer class I and II as in the Army. In 1939, the RAF abolished the rank of WOII and retained just the WOI rank, referred to as just warrant officer (WO), which it remains to this day. The RAF has no equivalent to WO2 (NATO OR-8), an RAF WO being equivalent to WO1 (NATO OR-9) and wearing the same badge of rank, the Royal coat of arms. The correct way to address a warrant officer is "sir" or "ma'am" by airmen and "mister or warrant officer -surname-" by officers. Most RAF warrant officers do not hold appointments as in the army or Royal Marines; the exception to this is the station warrant officer, who is considered a "first amongst equals" on an RAF station. Warrant officer is the highest non-commissioned rank and ranks above flight sergeant.

In 1946, the RAF renamed its aircrew warrant officers to master aircrew, a designation which still survives. In 1950, it renamed warrant officers in technical trades to master technicians, a designation which survived only until 1964.

The most senior RAF warrant officer by appointment, although holding the same rank as all other warrant officers, is the Warrant Officer of the Royal Air Force, known as the Chief of the Air Staff's Warrant Officer from the post's creation in 1996 until 2021.

United States

In the United States Armed Forces, a warrant officer (grade W-1 to W-5) is ranked as an officer above the senior-most enlisted ranks, as well as officer cadets and officer candidates, but below the officer grade of O‑1 (NATO: OF‑1). All warrant officers rate a salute from those ranked below them; i.e., the enlisted ranks. Warrant officers are highly skilled, single-track specialty officers, and while the ranks are authorized by Congress, each branch of the military selects, manages, and utilizes warrant officers in slightly different ways. For appointment to warrant officer (W-1), normally a warrant is approved by the service secretary of the respective branch of service. However, appointment to this rank can come via commission by the President, but this is less common. For the chief warrant officer ranks (CW‑2 to CW‑5), these warrant officers are commissioned by the President. Both warrant officers and chief warrant officers take the same oath of office as regular commissioned officers (O-1 to O-10).[36]

A small number of warrant officers command detachments, units, activities, vessels, aircraft, and armored vehicles, as well as lead, coach, train, and counsel subordinates. However, the warrant officer's primary task is to serve as a technical expert, providing valuable skills, guidance, and expertise to commanders and organizations in their particular field.[36]

All U.S. armed services employ warrant officer grades except the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Space Force. Although still technically authorized, the Air Force discontinued appointing new warrant officers in 1959, retiring its last chief warrant officer from the Air Force Reserve in 1992. Space Force inherited the same lack of warrant officers from the Air Force, although its inaugural Chief Master Sergeant, Roger A. Towberman, stated in a January 2021 interview that Space Force would study the issue and decide whether or not to introduce them.[37]

The U.S. Army utilizes warrant officers heavily[lower-alpha 1] and separates them into two types: Aviators and technical. Army aviation warrant officers pilot both rotary-wing and fixed wing aircraft and represent the largest group of Army warrant officers. Technical warrant officers in the Army specialize in a single branch technical area such as intelligence, sustainment, supply, military police, or special forces; and provide advice and support to commanders. For example, a military police officer and a military intelligence officer both have to be branch qualified in their respective fields, learning how to manage the entire spectrum of their profession. However, within those broad fields warrant officers include such specialists as CID Special Agents (a very specific track within the military police) and Counterintelligence Special Agents (a very specific track within military intelligence). These technical warrant officers allow for a soldier with subject matter expertise (like non-commissioned officers), but with the authority of a commissioned officer. Both technical and aviation warrant officers go through initial training and branch assignment at the Army Warrant Officer Candidate School (WOCS), followed by branch-specific training and education paths. Technical warrant officers are generally selected from the non-commissioned officer ranks (typically E-6 through E-9). Aviation warrant officer candidates can apply from all branches of service, including junior enlisted and non-prior service civilians (aviation warrant officers join through the Warrant Officer Flight Training Program).

The U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard discontinued the grade of W-1 in 1975, appointing and commissioning all new entrants as chief warrant officer two (pay grade W-2, with rank abbreviation of CWO2). This was to prevent a pay decrease that an entrant may take since all Navy chief warrant officers are selected strictly from the chief petty officer pay grades (E-7 through E-9). The Coast Guard allows E-6 personnel to apply for chief warrant officer rank, but only after they have displayed their technical ability by earning a placement in the top 50% on the annual eligibility list for advancement to E-7. In 2018, the U.S. Navy expanded the warrant program, re-implementing the W-1 pay grade for cyber warrant officers and accepting three new WO1s in fiscal year 2019.[38]

Warrant officers in the Army holding the rank of warrant officer 1 (WO1) are formally addressed as "Mr/Ms" [last name]. Upon promotion to chief warrant officer 2, "Chief" becomes an additional authorized term of address. WO1s are informally addressed as "Chief" by many soldiers as well. In the Navy, warrant officers are typically addressed as "Mr/Ms" [last name], "Chief Warrant Officer", or informally as "Warrant" regardless of their grade.

The U.S. Maritime Service (USMS), which is established at 46 U.S. Code § 51701, falls under the authority of the Maritime Administration of the Department of Transportation and is authorized to appoint warrant officers. In accordance with 46 U.S. Code § 51701, the USMS rank structure must be the same as that of the U.S. Coast Guard while uniforms worn are those of the U.S. Navy with distinctive USMS insignia and devices. The USMS has appointed warrant officers, of various specialty fields, during and after World War II.[39][40]

Warrant officer rank is also occasionally used in law enforcement agencies to grant status and pay to certain senior specialist officers who are not in command, such as senior technicians or helicopter pilots. As in the armed forces, they rank above sergeants, but below lieutenants. For example, the North Carolina State Highway Patrol had several warrant officer helicopter pilot positions from the 1960s until the mid-1980s. The WO insignia was a silver bar with a black square in the center. The WO ranks were abolished when the aviation program expanded and nearly twenty trooper pilot positions were created. The New York State Police rank of technical lieutenant is similar to a warrant officer rank insofar as it is used to grant commissioned officer authority to non-commissioned officers with extensive technical expertise.

| Service | CW5 or CWO5 | CW4 or CWO4 | CW3 or CWO3 | CW2 or CWO2 | WO1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

U.S. Army chief warrant officer 5 rank insignia |

U.S. Army chief warrant officer 4 rank insignia |

U.S. Army chief warrant officer 3 rank insignia |

U.S. Army chief warrant officer 2 rank insignia |

U.S. Army warrant officer 1 rank insignia | |

USMC chief warrant officer 5 rank insignia |

USMC chief warrant officer 4 rank insignia |

USMC chief warrant officer 3 rank insignia |

USMC chief warrant officer 2 rank insignia |

USMC warrant officer 1 rank insignia | |

U.S. Navy chief warrant officer 5 rank insignia |

U.S. Navy chief warrant officer 4 rank insignia |

U.S. Navy chief warrant officer 3 rank insignia |

U.S. Navy chief warrant officer 2 rank insignia |

U.S. Navy warrant officer 1 rank insignia | |

| Established in 1994; not implemented |  U.S. Coast Guard chief warrant officer 4 rank insignia |

U.S. Coast Guard chief warrant officer 3 rank insignia |

U.S. Coast Guard chief warrant officer 2 rank Insignia |

Discontinued in 1975 |

Gallery

Warrant officer

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Gambian National Army) Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Ghana Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Malawi Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Sierra Leone Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Eswatini Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Zambian Army) Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Zimbabwe National Army)

Warrant officer class 1

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Gambian National Army) Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Ghana Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Malawi Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Sierra Leone Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Eswatini Army)

Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Zambian Army) Warrant officer class 2

Warrant officer class 2

(Zimbabwe National Army)

See also

Notes

- see Senior Warrant Officer Advisory Council CW4 Richard C. Myers and CW5 Todd M. Boudreau (Spring 2011) Charging toward an even brighter future

References

- Welsh, David R. (2006). Warrant: The Legacy of Leadership as a Warrant Officer. Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-59652-053-0.

- "A Brief History of Warrant Rank in the Royal Navy". Naval-History.Net. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-87021-258-3.

- "Information sheet no 096: Naval Ranks" (PDF). National Museum of the Royal Navy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015.

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-87021-258-3.

- "Defence Force Regulations 1952". Australian Government, ComLaw. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "Australian Defence Force Badges of Rank and Special Insignia". Australian Government, Department of Defence. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- "Rank Categories". Bangladesh Army. Bangladesh Army. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "BAF Ranks". Bangladesh Army. Bangladesh Army. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "For Airmen". careerairforce.nic.in. Indian Air Force. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Kategori Pangkat". army.mod.gov.my/ (in Malagasy). Malaysian Army. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "RMN other ranks". navy.mil.my. Royal Malaysian Navy. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- "National Civil Defence Cadet Corps (NCDCC) / National Civil Defence Cadet Corps (NCDCC)". www.uniforminsignia.org. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- MINDEF, History Snippets, 1992 – The SAF Warrant Officer School, 7 January 2007. Accessed 19 March 2007.

- "CMPB | Ranks and drill commands". Central Manpower Base (CMPB). Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Minister approves new ranks for Warrant Officers" (PDF). South African Soldier. SA Department of Defence. September 2008. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- "The Executive Warrant Officer" (PDF). 4 October 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "The Command Warrant Officer (Cwo)" (PDF). 4 October 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Warrant Officer in a class of his own". Royal Navy: News and Events. 24 April 2013.

- "New Base Warrant Officer at Culdrose". Fleet Air Arm Officers Association News. 2 October 2013.

- "The Semaphore Circular May 2020". royal-naval-association.co.uk. Royal Navyal Association. 1 May 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

Our source was the Fleet Commander's Warrant Officer, a newly created post and itself part of the Navy Command Transformation programme. WO Mick Turnbull works alongside the Warrant Officer of the Naval Service as well as First and Second Sea Lords WOs. This is a change from the former situation where each fighting arm (Surface Ships, Submarines, Royal Marines, Reserves and Fleet Air Arm) had its own WO. It is one part of a shift to a whole naval force focus

- "Navy News March 2020" (PDF). royalnavy.mod.uk. Navy News. 1 March 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

Helping to deliver transformation is the new Warrant Officer of the Naval Service, WO1 Carl 'Speedy' Steedman. He will be working with the holders of two brand new positions; Second Sea Lord's Warrant Officer, WO1 Ian Wilson and Fleet Commander's Warrant Officer, WO1 Mick Turnbull, together with the RM Corps RSM, WO1 Dave Mason.

- "Command Warrant Officers" (PDF). whatdotheyknow.com. whatdotheyknow. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Single rate for warrant officers" (PDF). 201401 Navy News Jan 14. p. 35. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- @WO1MickTurnbull (2 February 2021). "Good afternoon the WO2 rank was kept in Service for the Royal Marines and Submariner engineers. However as part of Royal Navy Transformation the WO2 Rank has now been introduced across the Service. The first recipients were notified on 18 Jan 21 and others have now been selected" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Banham, Tony (2006). The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain's Forgotten Wartime Tragedy. Hong Kong University Press. p. 272. ISBN 9789622097711.

- "Army" (PDF). The London Gazette. No. 22585. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- "Royal army medical corps" (PDF). The London Gazette. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- Jones, Bruce (1 February 2015). "CGS outlines new British Army senior posts amid culling of generals". Jane's Defence Weekly.

- "NAVY—THE ROYAL MARINES—SER GEANTS.—QUESTION". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 29 July 1879. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "London Gazette, 2 December 1881". Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "London Gazette, 12 November 1915". Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "The London Gazette, 3 February 1920". Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- "London Gazette, 15 November 1910". Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "London Gazette, 15 June 1917". Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Warrant Officer History". U.S. Army Warrant Officer Career Center. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "Space Force Senior Enlisted Advisor Talks Future of Enlisted Force". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- Affairs, This story was written by Chief of Naval Personnel Public. "Navy Expands Cyber Warrant Program". www.navy.mil.

- 46 U.S. Code § 51701 (c) Ranks, Grades, and Ratings.— The ranks, grades, and ratings for personnel of the Service shall be the same as those prescribed for personnel of the Coast Guard.

- "United States Maritime Service Insignia of Rank and Distinctive Devices and Uniforms". www.usmm.org. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Ranks & insignia". joinbangladesharmy.army.mil.bd. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "Ranks and appointment". canada.ca. Government of Canada. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- Smaldone, Joseph P. (1992). "National Security". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Nigeria: a country study. Area Handbook (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 296–297. LCCN 92009026. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- "RAF Ranks". raf.mod.uk/. Royal Air Force. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Antigua & Barbuda Defence Force. "Paratus" (PDF). Regional Publications Ltd. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Ranks". Government of Botswana. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "KDF Ranks". mod.go.ke. Ministry of Defence - Kenya. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Ranks in the Army". Lesotho Defence Force. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Government Notice" (PDF). Government Gazette of the Republic of Namibia. Vol. 4547. 20 August 2010. pp. 99–102. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- "RDF Insignia". mod.gov.rw. Government of the Republic of Rwanda. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- "Rank structure". spdf.sc. Seychelles People's Defence Forces. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "Uniform: Rank insignia". army.mil.za. Department of Defence (South Africa). Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- "Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces Act" (PDF). The Uganda Gazette. Uganda Printing and Publishing Corporation. CXII (46): 1851–1854. 18 September 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.