Brook of Egypt

Brook of Egypt is the name used in some English translations of the Bible (e.g., JPS 1917, NKJV, NLT) for the Hebrew נַחַל מִצְרַיִם, naḥal mizraim ("Wadi of Egypt" NRSV), a river (bed) forming the southernmost border of the Land of Israel.[1] A number of scholars in the past identified it with Wadi el-Arish,[2] an epiphemeral river flowing into the Mediterranean sea near the Egyptian city of Arish, while other scholars, including Israeli archaeologist Nadav Na'aman and the Italian Mario Liverani believe that the Besor stream, just to the south of Gaza, is the "Brook of Egypt" referenced in the Bible.[3][4] A related phrase is nahar mizraim ("river of Egypt"), used in Genesis 15:18.

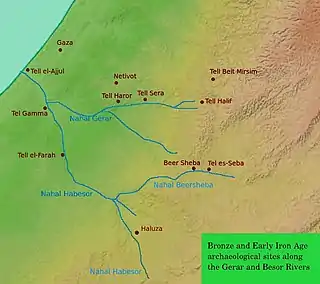

Nahal Besor

The Israeli archaeologist Nadav Na'aman and the Italian Mario Liverani have suggested that Wadi Gaza or Nahal Besor, was the Brook of Egypt.[3][4] Certainly, it was controlled by Egypt in the Late Bronze Age and inhabited by Philistines into the Iron Age.[5]

Wadi el-Arish

According to Exodus 13:18–20, the locality from which the Israelites journeyed after departing Egypt was Sukkot. The name Sukkot means "palm huts" in Hebrew and was translated El-Arish in Arabic. It lies in the vicinity of El-Arish, the hometown of the Jewish commentator Saadia Gaon who identified Naḥal Mizraim with the wadi of El-Arish.

The Septuagint translates Naḥal Mizraim in Isaiah 27:12 as Rhinocorura.

Although in later Hebrew the term naḥal tended to be used for small rivers, in Biblical Hebrew, the word could be used for any wadi or river valley.[6]

According to Sara Japhet,

"Nahal Mizraim" is Wadi el-Arish, which empties into the Mediterranean Sea about 30 miles south of Raphia, and "Shihor Mizraim" is the Nile.[7]

Possible interpretation as the Nile

One traditional Jewish understanding of the term Naḥal Mizraim is that it refers to the Nile. This view appears in the Palestinian Targum on Numbers 34:5, where נחלה מצרים in translated נילוס דמצריי ("the Nile of the Egyptians"; preserved in the Neophiti and Vatican manuscripts, as well as in Pseudo-Jonathan),[8] as well as in a few medieval commentators, such as Rashi and David Kimhi on Joshua 13:3.[9] However, most commentators, such as Targum Onkelos, Abraham Ibn Ezra, Bahya ben Asher, Samuel David Luzzatto, Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin and Moisè Tedeschi on Numbers 34:5, reject this interpretation.[10]

References

- Görg, M. (1992). Freedman, David Noel (ed.). Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary. New York: Doubleday. s.v. “Egypt, Brook of”.

- M. Patrick Graham; William P. Brown; Jeffrey K. Kuan (1 November 1993). History and Interpretation: Essays in Honour of John H. Hayes. A&C Black. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-567-26995-9.

- Nadav Na'aman, The Brook of Egypt and Assyrian Policy on the Egyptian Border. Tel Aviv 6 (1979), pp. 68-90

- Mario Liverani (1995). Neo-Assyrian geography, p. 111. Università di Roma, Dipartimento di scienze storiche, archeologiche e antropologiche dell'Antichità.

- Othmar Keel; Christoph Uehlinger (1998). Gods, goddesses, and images of God in ancient Israel. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-567-08591-7. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- The dictionary of classical Hebrew. David J. A. Clines, Society for Old Testament Study. Sheffield. 1993–2016. ISBN 1-85075-244-3. OCLC 29742583.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Sara Japhet, From the Rivers of Babylon to the Highlands of Judah: Collected Studies on the Restoration Period. Eisenbrauns, 2006 ISBN 157506121X p42

- "The Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon".

- "MikraotGedolot – AlHaTorah.org". mg.alhatorah.org.

- "MikraotGedolot – AlHaTorah.org". mg.alhatorah.org.