Walter Potter

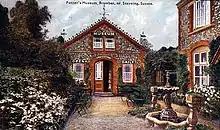

Walter Potter (2 July 1835 – 21 May 1918)[1][2] was an English taxidermist noted for his anthropomorphic dioramas featuring mounted animals mimicking human life, which he displayed at his museum in Bramber, Sussex, England. The exhibition was a well-known and popular example of "Victorian whimsy" for many years, even after Potter's death; however, enthusiasm for such entertainments waned in the twentieth century, and his collection was finally dispersed in 2003. His great, great granddaughter Charlotte Collins holds hope to return at least one piece to the family.

Walter Potter | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Walter Potter c. 1910 | |

| Born | 2 July 1835 |

| Died | 21 May 1918 (aged 82) |

| Occupation | Taxidermist |

| Known for | Assembled a popular collection of anthropomorphic dioramas. |

Early life and popularity

Walter Potter's family ran The White Lion pub in Bramber. Potter left school at the age of fourteen and began creating taxidermy pieces as a way to encourage people to visit the family's establishment.[3] His first attempt at taxidermy was to preserve the body of his own pet canary when he was a teenager.[4] At the age of 19, inspired by his sister, Jane, who showed him an illustrated book of nursery rhymes,[2] Potter produced what was to become the centrepiece of his museum, a diorama of "The Death and Burial of Cock Robin", which included 98 species of British birds.[4][5] This was so well-received that in 1861, he opened a separate display in the summer house of the pub.[4] While satisfying the Victorian demand for traditional stuffed animals to earn a living, Potter continued creating his dioramas and expanded into new premises in 1866, and again in 1880. As his museum expanded, Potter married a local girl, Ann Stringer Muzzell, and they had three children, Walter, Annie and Minnie.[6]

Amongst his scenes were "a rats' den being raided by the local police rats ... [a] village school ... featuring 48 little rabbits busy writing on tiny slates, while the Kittens' Tea Party displayed feline etiquette and a game of croquet. A guinea pigs' cricket match was in progress, and 20 kittens attended a wedding, wearing little morning suits or brocade dresses, with a feline vicar in white surplice."[5] Potter's attention to detail in these scenes has been noted, to the extent that "The kittens even wear frilly knickers under their formal attire!"[7] Apart from the simulations of human situations, he had also added examples of bizarrely deformed animals, such as two-headed lambs and four-legged chickens.[4]

Potter's collection, billed as "Mr Potter's Museum of Curiosities" was to build into a "world-famous example of Victorian whimsy", with special coach trips from Brighton being arranged;[5] and the village and Potter's museum were so popular that an extension was built to the platform at Bramber railway station.[4]

Later life, death, and decline of the museum

Potter suffered a stroke in 1914, from which he never fully recovered, and died at the age of 82 four years later;[2] he was buried in Bramber churchyard.[6] His museum, which by that time contained about 10,000 specimens,[2] was taken over by his daughter and grandson.[4] The Victorian enthusiasm for stuffed animals had waned by the museum's later days, and it deflected claims of animal cruelty by displaying notices stating that all the animals had died naturally and that "in any case, they were all over 100 years old".[5] The "Kittens' Wedding" scene, the last created by Potter in 1890,[8] was shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2001 as part of "The Victorian Vision" exhibition.[9]

The exhibits form the inspiration for the gothic thriller The Taxidermist's Daughter by Kate Mosse.[10]

Sale of the collection

The museum closed in the 1970s, and, after having been moved to Brighton and then to Arundel, was sold in 1984 to the owners of Jamaica Inn, Bolventor, Cornwall,[1] where it attracted more than 30,000 visitors each year.[7] The death of their taxidermist and economic considerations sapped the venture of its viability, and, when a buyer to maintain the collection intact did not come forward,[11] it was auctioned by Bonhams in 2003, realizing over £500,000.[12] "The Kittens' Wedding" was sold for £21,150, and "The Death and Burial of Cock Robin" was the highest-selling item of the sale, raising £23,500. Present at the auction were Peter Blake, Harry Hill and David Bailey.[12]

A bid of £1m offered by Damien Hirst for the entire collection had apparently been rejected by the auctioneers, and the owners sued Bonhams, arguing that this offer should have been accepted.[5] Shortly after the auction, Hirst wrote to The Guardian citing some of Potter's limitations as a taxidermist, saying "You can see he knew very little about anatomy and musculature, because some of the taxidermy is terrible—there's a kingfisher that looks nothing like a kingfisher".[13] He also showed appreciation for the displays: "My own favourites are these tableaux: there's a kittens' wedding party, with all these kittens dressed up in costumes, even wearing jewellery. The kittens don't look much like kittens, but that's not the point. There's a rats' drinking party, too which puts a different construction on Wind in the Willows. And a group of hamsters playing cricket."[13] About the auction, Hirst said, "I've offered £1m and to pay for the cost of the auctioneer's catalogue – just for them to take it off the market and keep the collection intact – but apparently, the auction has to go ahead. It is a tragedy."[13]

The White Lion pub, home of Potter's collection, has now been renamed The Castle Hotel.[14]

References

- "Walter Potter of Bramber West Sussex". Taxidermy4Cash.com. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Walter Potter (1835–1918)". ravishingbeasts.com. 3 November 2006. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- Robert Marbury (2014). Taxidermy Art: A Rogue's Guide to the Work, the Culture, and How to Do It Yourself. Artisan. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-57965-558-7. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Ketteman, Tony. "Mr Potter of Bramber". Steyning Museum. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- Morris, Pat (7 December 2007). "Animal magic". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Walter Potter". a case of curiosities. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- "Mr Potter's Museum of Curiosities". Bonhams. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- "The Sale of the Contents of Mr Potter's Museum of Curiosities". Bonhams. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- Harris, Marion (10 July 2001). "We Are Amused". Antiques And The Arts Online. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- The Taxidermist's Daughter by Kate Mosse | Hachette UK

- "Bid to save bizarre animal collection". The Argus. 10 September 2003. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Walter Potter's amazing tableaux take centre stage as museum makes more than £½ million". Bonhams. Archived from the original on 18 March 2006. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- Hirst, Damien (23 September 2003). "Mr Potter, stuffed rats and me". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- "The British Historical Taxidermy Society". britishhistoricaltaxidermy.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2009.