Walter Langton

Walter Langton (died 1321) of Castle Ashby[2] in Northamptonshire, was Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield and King's Treasurer. The life of Langton was strongly influenced by his uncle William Langton (d. 1279), Archbishop of York-elect, by Robert Burnell, Lord Chancellor of England and then by the years in which he served King Edward I. Lichfield Cathedral was improved and enriched at his expense.[3]

Walter Langton | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield | |

Walter Langton, 18th-century drawing of a now-lost stained-glass depiction in Lichfield Cathedral | |

| Elected | 20 February 1296 |

| Term ended | 9 November 1321 |

| Predecessor | Roger de Meyland |

| Successor | Roger Northburgh |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 23 December 1296 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 September 1243 Leicestershire |

| Died | 9 November 1321 (aged 78) |

| Buried | Lichfield Cathedral |

| Denomination | Catholic |

Origins

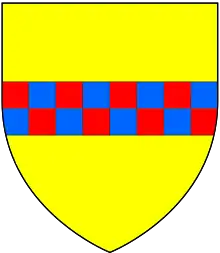

His origins were long unclear but following recent research (Hughes, 1992) it is now apparent that he was the eldest son of Simon Peverel[4] of "Langton" in Leicestershire,[5] the exact location of which estate is uncertain (see below). He thus adopted the surname "de Langton" in lieu of his patronymic. His brother (it is now established) was Robert Peverel (d. 1317) of Brington and Ashby David in Northamptonshire,[6] an ancestor of Joan de la Pole, suo jure 4th Baroness Cobham (d. 1434) "of Kent", whose prominent descendants the Brooke family, Barons Cobham, are known to have quartered the arms of Peverel of Langton (Gules, a fess between nine cross-crosslets or).[7] The Bishop, however, eschewed his paternal arms as well as surname, as his arms are said to have been Or, a fess chequy gules and azure.[8] Langton appears to have been no relation of his contemporary, John Langton, Bishop of Chichester.[3]

Estate of Langton

"Langton" is an ancient parish situated four miles north of Market Harborough containing the five estates of Church Langton (the site of the "mother church of the parish"), East Langton, Langton West, Thorpe Langton and Tur Langton, covering in total 4,409 acres. Although by tradition West Langton was the birth-place of the Bishop, the estate he later owned was Thorpe Langton.[9] From the 12th century the estate of Thorpe Langton was split into two fees, the "Huntingdon fee" and the "Basset fee", and it was the latter which was held by the Peverel family, from the Basset overlords. In 1279 Ralph Peverel held 3½ virgates in demesne and 2 virgates in villeinage, from his immediate feudal overlord a certain "Thomas de Langton", who in turn held of Richard Burdet, who held of Robert de Tateshall, who held of Ralph Basset, the tenant-in-chief. The Bishop succeeded Ralph Peverel as the principal tenant of the Basset fee, by a grant from Richard de Pydyngton, mesne lord and in 1300 he received a royal grant of free warren "over his demesne lands in Langton and Thorpe Langton". In 1307 his lands were declared forfeit, but in 1309 he is recorded as holding ¼ of a knight's fee in Thorpe Langton. On his death he held only 3 acres at Thorpe Langton.[10]

Career

Before royal service

According to Hughes (1991): "In October 1298 Langton was licensed by Henry of Newark, archbishop of York, to ordain Walter and Robert Clipston, (his nephews), then aged seven and five years respectively, to all minor orders".

Although there is little research on the issue, Langton may have entered the church at a similar age. It is known that his uncle William Langton became Dean of York in 1262 and he may have come under his uncle's supervision at that time. In 1265 his uncle William Langton was elected Archbishop of York, but his appointment was superseded by the Pope's appointment of Bonaventura. In public life both men adopted for surname de Langton", the name of their family's manor of Langton in Leicestershire.

Copies of charters preserved in his register, by which Langton granted land and the advowson of the church of Adlingfleet, Yorkshire, to Selby Abbey, clearly states his paternity: Langton names himself as "the son and heir of Simon Peverel".[11]

Keighley Shared Church is represented by St Andrew's Church at Keighley, West Yorkshire. Amongst its rectors is listed Walter de Langton, inducted 1272. More research into the Langton's life at this time may shed more light into his relationship with the wife of Sir John Lovetot.

It is said in the chronicles that King Edward I of England selected Langton for his service.

Servant of King Edward I

Though Lord Chancellor, Bishop Robert Burnell of Bath and Wells was also Archdeacon of York. It may be supposed through his duties in York he became a friend of William Langton and through the two men, Walter Langton was introduced to the King. The King must have liked the young man, for he selected him for his service and in later years Langton became "unquestionably Edwards's first minister and almost his only real confidant".

Appointed a clerk in the royal chancery, Langton became a favourite servant of Edward I, and was appointed Keeper of the wardrobe from 1290 to 1295. He took part in the suit over the succession to the Scottish throne in 1292, and visited France more than once on diplomatic business.[3] In 1293 he rushed to Lambeth to obtain a charter transferring the Isle of Wight to the king from Isabella de Fortibus who was near to death.[12] He became Treasurer from 1295 to 1307[13] and obtained several ecclesiastical preferments,. On 20 February 1296 he was elected bishop of Lichfield, being consecrated on 23 December.[14] As bishop he rebuilt the diocesan seat, Eccleshall Castle, in a more lavish style.[15]

Having become unpopular, the barons in 1301 vainly asked Edward to dismiss Langton; about the same time he was accused of murder, adultery and simony. Suspended from his office, he went to Rome to be tried before Pope Boniface VIII, who referred the case to Winchelsea, archbishop of Canterbury; the archbishop, although Langton's lifelong enemy, found him innocent, and this sentence was confirmed by Pope Boniface in 1303.[3] Little is said about the nature of the charges of witchcraft against Bishop Walter Langton.[16] By inference Pope Boniface VIII was charged, about the same time with Invocation, consultation of diviners, and other offenses, by officials of King Philip IV of France, about which more information is available.[17]

Accounts by historians say little about how Langton escaped the charges of witchcraft at the tribunal at the Vatican over the 2 years he had to defend himself there. But a strong protest from King Edward I saw Pope Boniface refer the case back to English jurisdiction. Langton was allowed to return to England and his was eventually found innocent. This incident represents a political struggle between the Archbishop Robert Winchelsea, the King and his councillor.

Throughout these difficulties, and also during a quarrel with the prince of Wales, afterwards Edward II, the treasurer was loyally supported by the king. Visiting Pope Clement V on royal business in 1305, Langton appears to have persuaded Clement to suspend Winchelsea; after his return to England he was the chief adviser of Edward I, who had already appointed him the principal executor of his will.[3][18]

After the King's death

There is an elaborate pictorial representation of the life of King Edward I in Langton's residence housed outside of the Cathedral of Lichfield.

Langton's position, however, was changed by the king's death in July 1307. The accession of Edward II and the return of Langton's enemy, Piers Gaveston, were quickly followed by the arrest of the bishop, his removal from office, and imprisonment at London, Windsor and Wallingford. His lands, together with a great hoard of movable wealth, were seized, and he was accused of misappropriation and venality. In spite of the intercession of Clement V and even of the restored Archbishop Winchelsea, who was anxious to uphold the privileges of his order, Langton, accused again by the barons in 1309, remained in prison after Edward's surrender to the ordainers in 1310.[3]

He was released in January 1312 and again became treasurer on the 23rd;[13] but he was disliked by the ordainers, who forbade him to discharge the duties of his office. Excommunicated by Winchelsea, he appealed to the pope, visited him at Avignon, and returned to England after the archbishop's death in May 1313. He was a member of the royal council from this time until his dismissal at the request of parliament in 1315.

Death, burial & succession

He died on 9 November 1321[14] and was buried in Lichfield Cathedral. His heir was his nephew Edmund Peverel, son of his brother Robert Peverel (d. 1317), said to have been murdered at Castle Ashby. Edmund Peverel left a daughter and heiress Margaret Peverel, who married Sir William de la Pole (1316–1366), a first cousin of Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk.[19]

Landholdings

Apart from his landholdings at "Langton" in Leicestershire (see above), he held other estates including Brington, and Newbottle, both in Northamptonshire, for which in 1307 he received a royal grant of free warren.[20] His chief seat appears to have been Castle Ashby in Northamptonshire, which he obtained in 1306 from Oliver la Zouche and in the same year received royal licence to crenellate, after which the manor obtained its prefix "Castle", having previously been called Ashby David.[2] He conveyed Brington and Castle Ashby to his brother Robert Peverel and his wife Alice, and the estates descended to their son Edmund Peverel, the Bishop's nephew.

Building works, See of Lichfield

Thomas Harwood (1806), historian of Lichfield Cathedral called Langton "another founder of this church"[21] and listed his building works as follows: He cleaned the ditch around the Close, and surrounded it with a stone wall: he built the cloisters, and expended two thousand pounds upon a monument for St. Chad. He laid the foundation of St. Mary's chapel, in the cathedral, an edifice of uncommon beauty, in which he was interred; but dying before it was finished, he bequeathed a sufficient sum of money in his will to complete it. He built bridges over the Minster pool, which made an easy communication with the city. One such bridge, now underground, is commemorated by a plaque.[22] He obtained a grant from the Crown to lay an impost, for twenty-one years, upon the inhabitants, to pave the streets. He improved the condition of the Vicars Choral, by augmenting their income, and by conferring upon them great privileges. He gave his own palace at the west end of the Close to them, and erected a new episcopal palace at the north-east end. This palace was spacious and splendid; the great hall of which was an hundred feet long, and fifty-six broad, painted with the coronation, marriages, wars, and funeral of his patron, K. Edward I.; and these costly decorations were remaining so late as the time of Erdeswicke, in 1603. He presented to the church large quantities of silver-plate, and many valuable vestments. He erected that noble gate at the west entrance into the Close, a beautiful structure, worthy of its munificent founder; and which, in April 1800, was, with a barbarous taste, pulled down, and the materials applied to lay the foundation of a pile of new buildings, for the residence of necessitous widows of clergymen. He also built another beautiful gate at the south entrance, which was removed about fifty years ago. He built or enlarged the castle at Eccleshall, the manor-houses of Heywood and Shugborough, and the palace in the Strand, London.[21]

Citations

- see File:WalterDeLangton Died1321 BishopOfCoventry&Lichfield AfterDugdale.png. The arms (apparently based on Dugdale's drawing) are blazoned slightly differently as Or, a fess compony azure and gules in Bedford, Blazons of Episcopacy, 1858, p.57, apparently based on Dugdale's depiction

- 'Parishes: Castle Ashby', in A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 4, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1937), pp. 230-236.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Langton, Walter". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 179.

- Jill Hughes, Episcopate of Walter Langton, Bishop of Coventry & Lichfield, 1296–1321 (Ph.D. thesis 1992)[Vol. 1: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11108/1/315105_vol1.pdf][Vol. 2: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11108/2/315105_VOL2.pdf] "Langton's register clarifies the bishop's connections with the Peverel family of Leicestershire and Northamptonshire and shows that he was a Peverel by birth. Copies of charters preserved in his register, by which Langton granted land and the advowson of the church of Adlingfleet, Yorks., to Selby abbey, clearly state his paternity; Langton names himself as the son and heir of Simon Peverel (Reference: Bishop Langton's Register, nos. 1291, 1292, 1293)..."(Bishop] Langton's mother, Amicia Peverel, was buried at Langton (Leicestershire)" Quoted in "C.P. Addition: Parentage of Sir Robert Peverel (living 1312) and his brother Bishop Walter de Langton (died 1321) "

- EB,1911

- Jill Hughes; Complete Peerage, 5 (1926): 76 (sub Engaine); Called "brother" in his inquisition post mortem

- See monument in Cobham Church, KentFile:Arms WilliamBrooke 10thBaronCobham (1527-1597) CobhamChurch Kent.xcf; see: D'Elboux, Raymond H. (1949). "The Brooke Tomb, Cobham". Archaeologia Cantiana. 62: 48–56, esp. pp.50-1.

- Or, a fess chequy gules and azure as tricked (or=or, b=blue/azure, g=gules) in a drawing by William Dugdale of a stained-glass image of the Bishop formerly in Lichfield Cathedral, see File:WalterDeLangton Died1321 BishopOfCoventry&Lichfield AfterDugdale.png. The arms (apparently based on Dugdale's drawing) are blazoned slightly differently as Or, a fess compony azure and gules in Bedford, Blazons of Episcopacy, 1858, p.57

- J M Lee and R A McKinley, 'Church Langton', in Victoria County History, A History of the County of Leicestershire: Volume 5, Gartree Hundred (London, 1964), pp. 193-213

- Lee & McKinley, Victoria County History

- Hughes, quoting "Bishop Langton's Register, nos. 1291, 1292, 1293"

- Barbara English, Forz , Isabella de, suo jure countess of Devon, and countess of Aumale (1237–1293), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition (subscription required), January 2008. Accessed: 5 January 2011

- Fryde Handbook of British Chronology p. 104

- Fryde Handbook of British Chronology p. 253

- "History of Eccleshall". Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- See (in French) Julien Théry-Astruc, "'Excès' et 'affaires d’enquête'. Les procédures criminelles de la papauté contre les prélats, de la mi-XIIe à la mi-XIVe siècle. Première approche", in La pathologie du pouvoir : vices, crimes et délits des gouvernants, ed. by Patrick Gilli, Leyde : Brill, 2016, p. 164-236, at p. 183, 197, 204, 217.

- See (in French) Jean Coste, Boniface VIII en procès. Articles d'accusation et dépositions des témoins (1303–1311), Rome, "L'Erma" di Bretschneider, 1995.

- Denton, J. H. (1980) Robert Winchelsey and the Crown (1284–1313). A Study in the Defense of Ecclesiastical Liberty, London, New York, Melbourne, Cambridge University Press.

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 46, Pole, William de la (d.1366),by Charles Lethbridge Kingsford

- Whellan Francis, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Northamptonshire, London, 1849, pp.289-90

- Thomas Harwood, History and Antiquities of the Church and City of Lichfield, pp.10-11

- "Walter Langton bronze plaque | Open Plaques".

References

- Jill Hughes: Walter Langton and his family. In: Nottingham Medieval Studies, 35 (1991), S. 70–76

- Alice Beardwood: The trial of Walter Langton, Bishop of Lichfield, 1307–1312. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia 1964

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Langton, Walter". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 179.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- More information is provided in a paper Walter Langton, bishop of Coventry and Lichfield 1296-1321: his family background by Dr Jill Hughes, published in the Nottingham Medieval Studies XXXV (1991). There is some interest in Bishop Walter Langton, due to his trial before the Vatican on charges of witchcraft.

- Hughes, J.B., ed. (2001). The Register of Walter Langton, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, 1296–1321, vol. 1. Canterbury & York Society. Vol. 91.

- Hughes, J.B., ed. (2007). The Register of Walter Langton, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, 1296–1321, vol. 2. Canterbury & York Society. Vol. 97.

- (in French) Théry-Astruc, Julien, "'Excès' et 'affaires d’enquête'. Les procédures criminelles de la papauté contre les prélats, de la mi-XIIe à la mi-XIVe siècle. Première approche", in La pathologie du pouvoir : vices, crimes et délits des gouvernants, ed. by Patrick Gilli, Leyde : Brill, 2016, p. 164-236, at p. 183, 197, 204, 217.