Wanda Gág

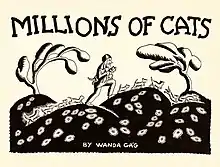

Wanda Hazel Gág (/ˈɡɑːɡ/ GAHG; March 11, 1893 – June 27, 1946) was an American artist, author, translator, and illustrator. She is best known for writing and illustrating the children's book Millions of Cats, the oldest American picture book still in print.[1] Gág was also a noted print-maker, receiving international recognition and awards.[2] Growing Pains, a book of excerpts from the diaries of her teen and young adult years, received widespread critical acclaim.[3] Two of her books were awarded Newbery Honors and two received Caldecott Honors.

Wanda Gág | |

|---|---|

Gág in December 1916 | |

| Born | Wanda Hazel Gag March 11, 1893 New Ulm, Minnesota, US |

| Died | June 27, 1946 (aged 53) New York City, US |

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Notable works | Millions of Cats (1928) |

| Notable awards | |

Early years

Wanda Hazel Gág was born March 11, 1893, in the German-speaking community of New Ulm, Minnesota,[4] to Elisabeth (née Biebl) Gag and the artist and photographer Anton Gag. The eldest of seven siblings, Wanda was 15 when her father died of tuberculosis.[5] His final words to her were: "Was der Papa nicht thun konnt', muss die Wanda halt fertig machen." (What Papa couldn't do, Wanda will have to finish.)[6]

Following his death, the family was on welfare and some townspeople thought that Wanda should quit high school and get a steady job to help support her family. Despite this pressure, Wanda continued with her high school education. While still a teenager her illustrated story Robby Bobby in Mother Goose Land was published in The Minneapolis Journal in their Junior Journal supplement.[7] After graduating in June 1912, she taught country school in Springfield, Minnesota, from November 1912 to June 1913.[8]

Art school

In 1913, Gág began a platonic relationship with University of Minnesota medical student Edgar T. Herrmann who exposed her to new ideas in art, politics and philosophy.[9] With a scholarship (and the aid of friends), she attended The Saint Paul School of Art in 1913 and 1914.[10] From 1914 to 1917 she attended The Minneapolis School of Art under the patronage of Herschel V. Jones.[11][12] While there, she became friends with Harry Gottlieb and Adolf Dehn.[13] Her first illustrated book commission (as Wanda Gäg) was A Child’s Book of Folk-Lore— Mechanics of Written English by Jean Sherwood Rankin (1917).[14]

New York

In 1917, Gág won a scholarship to the Art Students League of New York where she took classes in composition, etching and advertising illustration.[15] By 1919, Gág was earning her living as a commercial illustrator.[16]

During her time in New York she became a member of the Society of American Graphic Artists. In 1921, she became a partner in a business venture called Happiwork Story Boxes. The boxes were decorated with story panels on its sides.[17]

An illustration of Gág's was published in Broom: An International Magazine of the Arts in 1921.[18] Gág's art exhibition in the New York Public Library in 1923 was her first solo show. She began signing her name "Gág" around this time.[19]

In 1924, Gág's work was published in a short-lived folio-style magazine with artist William Gropper.[20] In 1925 she created a series of illustrated crossword puzzles for children that was syndicated in several newspapers.[21] Gág's one-woman-show in the Weyhe Gallery in 1926 led to her being acclaimed as "… one of America’s most promising young graphic artists… " and was the start of a lifelong relationship with its manager, Carl Zigrosser.[22][23] She began to sell her lithographs, linoleum block prints, water colors and drawings through the gallery.

In 1927, her article These Modern Women: A Hotbed of Feminists was published in The Nation, drawing the attention of Alfred Stieglitz and prompting Egmont Arens to write: "The way you solved that problem (her relationship with men) seems to me to be the most illuminating part of your career. You have done what all the other ‘modern women’ are still talking about."[24][25] Gág’s illustrations were published on the covers of the leftist magazines The New Masses and The Liberator.[26]

In 1928, Gág hand-colored some of Rockwell Kent's illustrations in a limited edition of Candide.[27]

In a 1929 New York Times review, Elisabeth Luther Cary described Gág's print Stone Crusher: "Pure imagination leaps out from dusky shadows and terrifies with light, an emotional source difficult to analyze."[28]

Her work was recognized internationally and was selected for inclusion in the American Institute of Graphic Arts Fifty Prints of the Year in 1928, 1929, 1931, 1932, 1936, 1937 and 1938.[29] In 1939 Gág's work was shown at The Museum of Modern Art exhibition Art in Our Time and at the New York World's Fair American Art Today show.[30]

Works for children

In 1927 Gág's illustrated story Bunny's Easter Egg was published in John Martin's Book, a magazine for children.[31] Gág's work caught the attention of Ernestine Evans, director of Coward-McCann's children's book division. Evans was delighted to learn that Gág had children's stories and illustrations in her folio and asked her to submit her own story with illustrations. The result, Millions of Cats, had been developed from a story that Gág had written to entertain the children of friends. It was published in 1928.[32] Anne Carroll Moore wrote: "… It bears all the hallmarks of becoming a perennial favorite among children, and it takes a place of its own, both for the originality and strength of its pictures and the living folk-tale quality of its text. A book of universal interest to children living anywhere in the world… A kinship with all children made her respect their intelligence, and gave them at once ease and joy in her company. With as sure an instinct for the right word for the ear, as for the right line for the eye, Wanda Gág became quite unconsciously a regenerative force in the field of children's books."[33][34] Millions of Cats is on the New York Public Library's list of 100 Great Children's Books.[35]

In 1935 Gág published the "proto-feminist" Gone is Gone; or, the Story of a Man Who Wanted to Do Housework.[36]

To encourage the reading of fairy-tales, Gág translated and illustrated Tales from Grimm in 1936. English critic Humbert Wolfe, commenting on Gág's translation, wrote: "From the very first page it was clear that Miss Gág was chopping away a perfect brushwood of clumsy phraseology to let in the light."[37] Two years later she translated and illustrated the Grimm story Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in reaction to the "trivialized, sterilized, and sentimentalized" Disney movie version.[38] Her essay I Like Fairy Tales was published in the March 1939 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. More Tales from Grimm was published posthumously in 1947. Four of her translated fairy tales were later released with illustrations by Margot Tomes.

Personal life

Gág enjoyed living and working in the country. In the early 1920s she spent summers drawing at various locations in rural New York and Connecticut.[17] She rented a three-acre farm (Tumble Timbers) in Glen Gardner, New Jersey, from 1925 to 1930, and later purchased a larger farm (All Creation) in Milford, New Jersey in 1931.[39]

She continued to support her unmarried adult siblings, some of whom lived with her from time to time. Gág's brother Howard did the hand lettering for most of her picture books and Wanda also encouraged her sister Flavia to create illustrated books for children.[40]

In addition to Earle Humphreys (her long-time paramour and business manager) Gág had, sometimes concurrently, other lovers including: Adolph Dehn, Lewis Gannett, Carl Zigrosser, and Dr. Hugh Darby. She married Humphreys on August 27, 1943.[41]

Gág died from lung cancer in New York City, aged 53, on June 27, 1946.[42]

Memorials

Gág was honored by The Horn Book Magazine in a tribute issue in 1947.[43] Her childhood home in New Ulm, Minnesota has been restored and is now the Wanda Gág House, a museum and interpretive center that offers tours and educational programs.[44]

In 1992, Millions of Cats was featured on the television series Shelley Duvall's Bedtime Stories, narrated by James Earl Jones.[45] A bronze sculpture of Gág (with one of her cats) by Jason Jaspersen was erected at the public library of New Ulm, Minnesota, in 2016.[46][47] In 2017 The Sandbox Theatre in Minneapolis produced In The Treetops, a new play that focused on Gág's childhood years.[48]

Awards

The books Millions of Cats and The ABC Bunny were recipients of a Newbery Honor. Both Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Nothing at All received a Caldecott Honor.

Wanda Gág was posthumously honored with The Lewis Carroll Shelf Award in 1958 and The Kerlan Award in 1977. The Wanda Gág Read Aloud Book Award is awarded each year by the University of Minnesota, Moorhead.

In 2018, Gág was posthumously honored with The Museum of Illustration at the Society of Illustrators Original Art Lifetime Achievement Award.[49]

Archives

Gág's prints, drawings, and watercolors are in the collections of The Minneapolis Institute of Arts,[50] The Whitney Museum[51] and other museums around the world. Gág's papers, manuscripts and matrices are held in the Kerlan Collection[52] at the University of Minnesota, The New York Public Library, The Free Library of Philadelphia and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.[53]

Works

Books

Writer and illustrator:

- Batiking at Home: a Handbook for Beginners, Coward McCann, 1926

- Millions of Cats, Coward McCann, 1928

- The Funny Thing, Coward McCann, 1929

- Snippy and Snappy, Coward McCann, 1931

- Wanda Gág’s Storybook (includes Millions of Cats, The Funny Thing, Snippy and Snappy), Coward McCann, 1932

- The ABC Bunny, Coward McCann, 1933

- Gone is Gone; or, the Story of a Man Who Wanted to Do Housework, Coward McCann, 1935

- Growing Pains: Diaries and Drawings for the Years 1908–1917, Coward McCann, 1940

- Nothing At All, Coward McCann, 1941

Translator and illustrator:

- Tales from Grimm, Coward McCann, 1936

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Coward McCann, 1938

- Three Gay Tales from Grimm, Coward McCann, 1943

- More Tales from Grimm, Coward McCann, 1947

Illustrator only:

- A Child’s Book of Folk-Lore— Mechanics of Written English, by Jean Sherwood Rankin, Augsburg, 1917

- The Oak by the Waters of Rowan, by Spencer Kellogg Jr, Aries Press, New York, 1927

- The Day of Doom, by Michael Wigglesworth, Spiral Press, 1929

- Pond Image and Other Poems, by Johan Egilsrud, Lund Press, Minneapolis, 1943

Translator only:

- The Six Swans, illustrations by Margot Tomes, Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1974

- Wanda Gág's Jorinda and Joringel, illustrations by Margot Tomes, Putnam, 1978

- Wanda Gag's the Sorcerer's Apprentice illustrations by Margot Tomes, Putnam, 1979

- Wanda Gag's The Earth Gnome, illustrations by Margot Tomes, Putnam, 1985

- The Sweet Porridge, illustrations by Jill McDonald [et al.], Methuen Educational, 1966.[52]

References

- Gregory, Alice. "Juicy As a Pear: Wanda Gág's Delectable Books". The New Yorker, April 24, 2014.

- Winnan, Audur, Wanda Gág. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993, pp. 71–77.

- Hoyle, Karen Nelson. Introduction in Growing Pains: Diaries and Drawings for the Years 1908–1917. Saint Paul, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1984, pg. xviii.

- "LibGuides: Wanda Gág: Illustrator & Author: Overview".

- Winnan, pg. 2.

- Gág, Wanda, Growing Pains Putnam, 1940 pg. xxxi.

- Cox, Richard W., The Bite of the Picture Book, Minnesota History Magazine, Fall 1974, pg. 250.

- Winnan, pg. 89.

- Winnan, pg. 5

- Winnan, pg. 2

- Gág, pg. 314

- Winnan, pg. 4

- "Wanda Gág papers, 1892–1968". dla.library.upenn.edu.

- Rankin, Jean Sherwood; Gág, Wanda (November 20, 1917). Mechanics of written English: a drill in the use of caps and points through the rimes of Mother Goose. Augsburg Publishing House – via HathiTrust.

- Gág, pp. 459, 466

- Hoyle, Karen Nelson, Wanda Gág, a Life of Art and Stories pp. 8–10, University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

- Hoyle, pp. 10–13

- Loeb, Harold, Broom, 1921, vol. II, no. 2

- Winnan, pg. 13

- Winnan, pg. 15

- Winnan, pg. 239

- L’Enfant, Julie, The Gág Family, Afton Historical Society Press, 2002, pg. 123

- The New Yorker: November 13, 1926, pg. 90

- Winnan, pp. 36, 71

- L'Enfant, pg. 130

- Hemingway, Andrew, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement 1926–1956, 2002

- Candide, Voltaire and Kent, Random House: New York, 1928

- New York Times, December 15, 1929.

- Winnan, pp. 72–76.

- L'Enfant, pg. 156.

- Gág, Wanda, John Martin's House vol. XXXV, issue no. 4

- Winnan, p. 36

- Millions of Cats dust jacket, second edition, 1928

- Minnesota Biographical Dictionary, Somerset Publishers, Inc. New York, 1993, p. 121.

- "Best Books for Kids 2021". The New York Public Library.

- Popova, Maria, The Story of a Man Who Wanted to do Housework: A Proto-Feminist Children's Book from 1935. Brain Pickings site.

- Wolfe, Humbert, "Golden Lads and Lasses". The Observer, December 5, 1937.

- Silvey, Anita. The Essential Guide to Children’s Books and Their Creators. Houghton Mifflin, 2002, p. 171.

- Winnan, pp. 71–73

- Shuldt, Clay, New Ulm Journal, July 29, 2010.

- Winnan, pp. 9, 44, 55, 61

- L'Enfant, pg. 165

- The Horn Book Magazine, issue 23, May–June 1947

- Wanda Gág House, accessed June 2012

- "Blumpoe the Grumpoe Meets Arnold the Cat/Millions of Cats". May 26, 1992 – via IMDb.

- "Wanda Gag Monument".

- Schuldt, Clay, New Ulm Journal, November 26, 2016.

- "In The Treetops (2017) |". Archived from the original on September 16, 2017.

- Schuldt, Clay, New Ulm Journal, November 14, 2018.

- "🔎 wanda gág | Mia".

- "Wanda Gag". whitney.org.

- "Search Results". Libraries of University of Minnesota. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- Chevalier, Tracy (ed.). Twentieth-Century Children's Writers. Chicago: St. James Press, 1989, p. 370.

Further reading

| Library resources about Wanda Gág |

| By Wanda Gág |

|---|

- Cox, Richard W., The Bite of the Picture Book, pp. 238–254, Minnesota History Magazine, Fall, 1975[1]

- Hoyle, Karen, Wanda Gág, Twayne Publishers, 1994

- Winnan, Audur, Wanda Gág: A Catalogue Raisonne of the Prints , Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993

Selected prints

- Airtight Stove, 1933

- Backyard Corner, 1930

- Evening, 1928

- The Forge, 1932.

- Gumbo Lane, c. 1928

- Macy’s Stairway, 1940–41

- Spinning Wheel, 1927

- Ploughed Fields, 1936

- Winter Garden, 1936

External links

- Works by Wanda Gág at Faded Page (Canada)

- Wanda Gág in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Works by Wanda Gág, National Gallery of Art

- Wanda Gág – Rights and Restrictions Information (Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress)

- Wanda Gág House

- Collection summary to the Wanda Gág Papers at the University of Minnesota Libraries Children's Literature Research Collections

- Finding aid to the Wanda Gág papers at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries

- Finding aid to the Wanda Gág papers Archived October 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine at Penn State University's Special Collections Library

- Wanda Gág at Library of Congress, with 52 library catalog records

- Overview of Wanda Gag archives at University of Minnesota Kerlan Collection, All About Kids! TV Series #259 (1998)

- "Minnesot Historical Society" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2016.