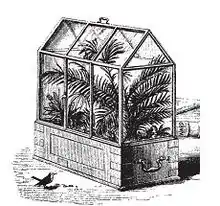

Wardian case

The Wardian case was an early type of terrarium, a sealed protective container for plants. It found great use in the 19th century in protecting foreign plants imported to Europe from overseas, the great majority of which had previously died from exposure during long sea journeys, frustrating the many scientific and amateur botanists of the time. The Wardian case was the direct forerunner of the modern terrarium and vivarium and the inspiration for the glass aquarium. It is named after Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791–1868) of London, who promoted the case after experiments.[1]

He published a book titled On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases in 1842.[2] A Scottish botanist named A. A. Maconochie had created a similar terrarium almost a decade earlier, but his failure to publish meant that Ward received credit as the sole inventor.[3]

History and development

Ward was a physician with a passion for botany. His personally collected herbarium amounted to 25,000 specimens. The ferns in his London garden in Wellclose Square, however, were being poisoned by London's air pollution, which consisted heavily of coal smoke and sulphuric acid.

Ward also kept cocoons of moths and the like in sealed glass bottles, and in one, he found that a fern spore and a species of grass had germinated and were growing in a bit of soil. Interested but not yet seeing the opportunities, he left the seal intact for about four years, noting that the grass actually bloomed once. After that time however, the seal had become rusted, and the plants soon died from the bad air.[4] Understanding the possibilities, he had a carpenter build him a closely fitted glazed wooden case and found that ferns grown in it thrived.

Ward published his experiment and followed it up with a book in 1842, On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases.

English botanists and commercial nurserymen had been passionately prospecting the world for new plants since the end of the 16th century, but these had to travel as seeds or corms, or as dry rhizomes and roots, as salty air, lack of light, lack of fresh water and lack of sufficient care often destroyed all or almost all plants even in large shipments.[4] With the new Wardian cases, tender young plants could be set on deck to benefit from daylight and the condensed moisture within the case that kept them watered, but protected from salt spray.[3]

The first test of the glazed cases was made in July 1833, when Ward shipped two specially constructed glazed cases filled with British ferns and grasses all the way to Sydney, Australia, a voyage of several months that found the protected plants still in good condition upon arrival. Other plants made a return trip: a number of Australian native species that had never survived the transportation previously.[3] The plants arrived in good shape, after a stormy voyage around Cape Horn.

One of Ward's correspondents was William Jackson Hooker, later director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Hooker's son Joseph Dalton Hooker was one of the first plant explorers to use the new Wardian cases, when he shipped live plants back to England from Aotearoa in 1841, during the pioneering voyage of HMS Erebus that circumnavigated Antarctica.

Wardian cases soon became features of stylish drawing rooms in Western Europe and the United States. In the polluted air of Victorian cities, the fern craze and the craze for growing orchids that followed owed much of their impetus to the new Wardian cases.

More importantly, the Wardian case unleashed a revolution in the mobility of commercially important plants. In the 1840s, Robert Fortune used Wardian cases to ship 20,000 tea plants to British India, smuggling them out of Shanghai, China, to begin the tea plantations of Assam. In 1860, Clements Markham used Wardian cases to smuggle the cinchona plant out of South America.[3] In the 1870s, after germination of imported hevea seeds in the heated glasshouses of Kew, seedlings of the rubber tree of Brazil were shipped successfully in Wardian cases to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the new British territories in Malaya to start the rubber plantations.

Wardian cases have thus been credited for helping break geographic monopolies in the production of important agricultural goods.[3]

Kew Gardens used Wardian cases to ship plants abroad up until 1962.[3]

The oldest surviving Wardian case is believed to be from circa 1880, discovered at Tregothnan in 1999.

Ward was always active in the Society of Apothecaries of London, of which he became Master in 1854. Until very recently, the Society managed the Chelsea Physic Garden, London, the second oldest botanical garden in the UK. Ward was a founding member of both the Botanical Society of Edinburgh and the Royal Microscopical Society, a Fellow of the Linnean Society and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

See also

References

- Allaby, Michael (2010). Plants, Food, Medicine and the Green Earth. New York: Facts on File. p. 103. ISBN 9781438129679.

- Thacker, Christopher (1985). The History of Gardens. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 237. ISBN 9780520056299.

- Maylack, Jen (12 November 2017). "How a Glass Terrarium Changed the World". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Gadient, Hansjörg (12 September 2010). "Exotische Pflanzen - Matrosen sind keine Gärtner". Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 6 September 2011.

Further reading

- Allen, David Elliston (1969). The Victorian Fern Craze. London: Hutchinson.

- Hershey, David (May 1996). "Doctor Ward's Accidental Terrarium". The American Biology Teacher. 58 (5): 276–281. doi:10.2307/4450151. JSTOR 4450151.

- Boyd, Peter D. A. (2002-01-02). "Pteridomania - the Victorian passion for ferns". Antique Collecting. Revised: web version. 28 (6): 9–12. Retrieved 2007-10-02.