Warm Springs Indian Reservation

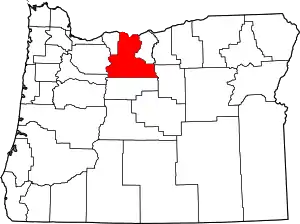

The Warm Springs Indian Reservation consists of 1,019 square miles (2,640 km2) in north-central Oregon, in the United States, and is governed by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs.

Warm Springs Indian Reservation | |

|---|---|

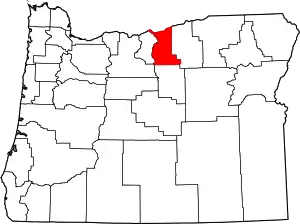

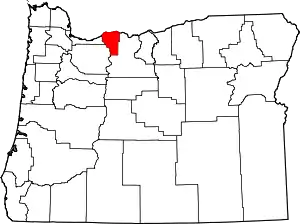

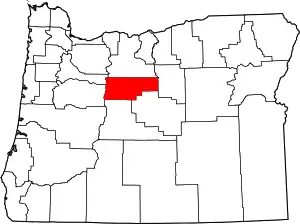

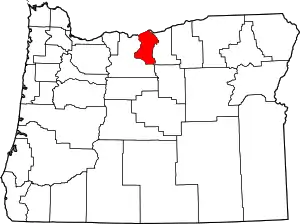

Location of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation and former tribal area | |

| Coordinates: 44°52′12″N 121°27′14″W | |

| Tribe | Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,640 km2 (1,019 sq mi) |

| Website | Official website |

Tribes

Three tribes form the confederation: the Wasco, Tenino (Warm Springs) and Paiute. Since 1938 they have been unified as the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs.

History

The reservation was created by treaty in 1855, which defined its boundaries as follows:

Commencing in the middle of the channel of the Deschutes River opposite the eastern termination of a range of high lands usually known as the Mutton Mountains; thence westerly to the summit of said range, along the divide to its connection with the Cascade Mountains; thence to the summit of said mountains; thence southerly to Mount Jefferson; thence down the main branch of Deschutes River; heading in this peak, to its junction with Deschutes River; and thence down the middle of the channel of said river to the place of beginning.

The Warm Springs and Wasco bands gave up ownership rights to a 10,000,000-acre (40,000 km2) area, which they had inhabited for over 10,000 years, in exchange for basic health care, education, and other forms of assistance as outlined by the Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon (June 25, 1855). Other provisions of the Treaty of 1855 ensured that tribal members retained hunting and fishing rights in the "Natural and Accustomed Area" which they had vacated. These treaty hunting and fishing rights are rights that were retained by the tribe and are not "special rights" granted by the U.S. government.[1]

In 1879, the U.S. government moved about 38 Paiutes to the reservation and around 70 more in 1884, despite that tribe's history of conflict with Columbia River tribes.[2]

The borders of the reservation were under dispute for 101 years, during what became known as the McQuinn Strip boundary dispute. In 1871, a surveyor named T.B. Handley measured the land, determining that it was smaller than outlined in the treaty of 1855. The Warms Spring people objected and, in 1887, a surveyor named John A. McQuinn determined that they were correct; Handley had incorrectly measured the reservation's boundaries. By this time, settlers had moved onto the disputed land. The government offered the Warm Springs people a cash settlement for the land, but the Warms Springs people refused it. In 1972, Public Law 92-427 restored the land to the Warm Springs people.[2]

Geography

The reservation lies primarily in parts of Wasco County and Jefferson County, but there are smaller sections in six other counties; in descending order of land area they are: Clackamas, Marion, Gilliam, Sherman, Linn and Hood River counties. (The Hood River County portion consists of tiny sections of non-contiguous off-reservation trust land in the northeast corner of the county.) The reservation is 105 miles (169 km) southeast of Portland; 348,000 acres (1,410 km2), over half, is forested.

Demographics

Its 2000 census total population was 3,314 inhabitants.

The reservations's only significant population center is the community of Warm Springs (also known as the Warm Springs Agency), which comprises over 73 percent of the reservation's population. As of 2003, the reservation was home to a tribal enrollment of over 4,200.

Culture

The Warm Springs Reservation is one of the last holdouts in the U.S. of speakers of the Chinook Jargon because of its utility as an intertribal language. The forms of the Jargon used by elders in Warm Springs vary considerably from the heavily-creolized form at Grand Ronde.

Kiksht, Numu and Ichishkiin Snwit languages are taught in the Warm Springs Reservation schools.[3]

The Museum at Warm Springs houses a large collection of North American Indian artifacts. It was opened in 1993.

Economy

The biggest source of revenue for the tribes is hydroelectric (Warm Springs Power Enterprises) projects on the Deschutes River. The tribes also operate Warm Springs Forest Products Industries.

Many tribal members engage in ceremonial, subsistence, and commercial fisheries in the Columbia River for salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon. Tribal members also fish for salmon and steelhead for subsistence purposes in the Deschutes River, primarily at Sherars Falls. Tribal members also harvest Pacific lamprey at Sherars Falls and Willamette Falls. The tribe's fishing rights are protected by treaty and re-affirmed by court cases such as Sohappy v. Smith and United States v. Oregon.

Tourism

In 1964, the first part of the Kah-nee-ta resort was completed – Kah-nee-ta Village – a lodging complex with a motel, cottages, and tipis. The resort eventually included a lodge, casino, convention center, and golf course. Due to lack of rentability, the resort was closed in September 2018.[4]

The Indian Head Casino on U.S. Route 26 opened in February 2012. It has 18,000 square feet (1,700 m2) of gaming space,[5] with 500 slot machines and 8 blackjack tables.[6] The tribes expect the casino to net $9 to 12 million annually.[7] The casino previously operated at Kah-Nee-Ta, where it had only 300 slot machines and made $2 to 4 million a year.[8] The new location was intended to be more accessible to travelers, since Kah-Nee-Ta is located about a half an hour from Highway 26.

Other business ventures

In 2016, the tribe's lumber mill, also located on Highway 26 near the village of Warm Springs, shut down. It had been operating for decades but output had declined in recent years. One solution proposed by a tribal entity, Warm Springs Ventures, to create new revenue and jobs for the tribe was the launch of three new business ventures: cannabis cultivation, extraction and distribution; drone training, certification and manufacture; and a carbon offset venture that would sell carbon offsets to major polluters. All three ventures were expected to be operating sometime in 2017. The tribe was awarded the right by the Federal Aviation Administration to certify drone operators in 2016. The cannabis project was approved by a vote of tribal members but as of October 2016 still faced administrative and funding challenges.[9]

Ecology

Biologists of the Confederated Tribe of the Warm Springs have assisted the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife in tracking the repopulation of wolves in Oregon. Wolves are dispersing into territory where they haven’t lived for decades including the northern Cascades region.[10] The biologists fitted OR-93 with a purple radio collar in June 2020.[11] The two-year-old male wolf had left his White River pack and became the 16th documented gray wolf in the repopulation of wolves in California when he reached Mono County, east of Yosemite National Park in the central Sierra Nevada in February 2021[12] Two adult wolves were found on the reservation in December 2021 by the biologists and two pups were caught on a trail camera in August 2022. These resident wolves brought the total number of known wolf groups in the region to three.[13]

Infrastructure

Water from the Deschutes River goes through a treatment facility and serves around 3,800 people.[14]

Gallery

View of a road in the Warm Springs Reservation

View of a road in the Warm Springs Reservation Road to the now closed Kah-Nee-Ta Resort

Road to the now closed Kah-Nee-Ta Resort.jpg.webp) Mount Hood (as seen from Warm Springs Reservation)

Mount Hood (as seen from Warm Springs Reservation).jpg.webp) Mount Jefferson (as seen from Warm Springs Reservation)

Mount Jefferson (as seen from Warm Springs Reservation)

References

- Warm Springs Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Oregon, United States Census Bureau

- Miller, Robert J. (2006). "Native America, Discovered and Conquered | Indian Treaties as Sovereign Contracts". Lewis & Clark Law School. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007.

- Colley, Brook (2018). Power in the Telling: Grand Ronde, Warm Springs, and Intertribal Relations in the Casino Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780295743363.

- Joanne B. Mulcahy (2005). "Warm Springs: A Convergence of Cultures" (Oregon History Project). Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- "End of an era: The Kah-Nee-Ta Resort closes". opb.org/news. Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Novet, Jordan (July 30, 2011). "What's going up? Indian Head Casino on Warm Springs reservation". The Bulletin. Bend, OR. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Nogueras, David (February 2, 2012). "New casino set to open along Highway 26". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Marlowe, Erin Foote (February 15, 2012). "A new beginning: Indian Head Casino gives Warm Springs chance for economic development". The Source Weekly. Bend, OR. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Taylor, Duffie (January 25, 2012). "New casino, new location: Warm Springs tribes are betting on a site a little closer to Bend". The Bulletin. Bend, OR. Retrieved May 31, 2012 – via NewsBank.

- Cook, Dan (November 3, 2016). "Pot Gamble". Oregon Business Magazine.

- Pettigrew, Jashayla (September 13, 2022). "New wolf family spotted in Oregon. What this means for conservation efforts". KOIN. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Orlean, Susan (December 14, 2021). "The Wolf That Roamed to Southern California". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- Murdock, Jason (March 1, 2021). "Scientists say first wolf found near Yosemite for century is a "beacon of hope"". Newsweek. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- Rush, Claire (September 14, 2022). "Oregon confirms new wolves in northern Cascade Mountains". AP News. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Land, Joni Auden (December 21, 2022). "Warm Springs will receive nearly $24 million to replace problem-prone water treatment facility". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

External links

- Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs

- Text of Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon, 1855 from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

- Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission - member tribes include the Warm Springs