Split Agreement

The Split Agreement or Split Declaration (Serbo-Croatian: Splitski sporazum or Splitska deklaracija) was a mutual defence agreement between Croatia, the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, signed in Split, Croatia on 22 July 1995. It called on the Croatian Army (HV) to intervene militarily in Bosnia and Herzegovina, primarily in relieving the siege of Bihać.

| Declaration on implementation of the Washington Agreement, joint defence against Serb aggression and achievement of a political solution in accordance with the efforts of the international community | |

|---|---|

Signing of the Split Agreement | |

| Signed | 22 July 1995 |

| Location | Split, Croatia |

| Mediators | Süleyman Demirel |

| Signatories | Franjo Tuđman, Alija Izetbegović, Krešimir Zubak, Haris Silajdžić |

| Parties | |

The Split Agreement was a turning point in the Bosnian War as well as an important factor in the Croatian War of Independence. It led to a large-scale deployment of the HV in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the capture of strategic positions in Operation Summer '95. This in turn allowed the quick capture of Knin, the capital of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), and the lifting of the siege of Bihać soon thereafter, during Operation Storm. Subsequent HV offensives in Bosnia and Herzegovina, supported by the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO), as well as NATO air campaign in Bosnia and Herzegovina, shifted the military balance in the Bosnian War, contributing to the start of peace talks, leading to the Dayton Agreement.

Background

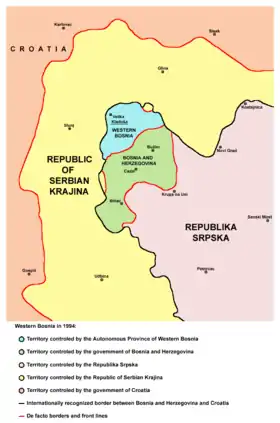

In November 1994, the Siege of Bihać entered a critical stage as the Army of the Republika Srpska (VRS)—the Bosnian Serb military—and forces of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) (an unrecognized state established following the Serb insurrection in Croatia)[1] came close to capturing the Bosnian town. Bihać was a UN-designated "safe area", controlled by the 5th Corps of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH), supported by the Croatian Defence Council (HVO)—the main military force of the Bosnian Croats. It was thought that the capture of Bihać by Serb forces would escalate the war and worsen a growing rift between the United States, France and the United Kingdom, with the U.S. and European powers advocating different approaches to preservation of the area.[2] In addition, it was feared that Bihać would turn into the worst humanitarian disaster of the war.[3] Furthermore, denying Bihać to the RSK or Republika Srpska was strategically important to Croatia, which was fighting the Croatian War of Independence against the RSK.[4] The Chief of the Croatian General Staff Janko Bobetko thought that the possible fall of Bihać would represent the end of Croatia's war effort.[5] It was considered that if the area were captured by Serb forces, it would allow for the consolidation of the territory held by Serb forces in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as redeployment of RSK and VRS troops to reinforce other areas.[6]

In a meeting of the Croatian and US Governments and military officials held on 29 November 1994, the Croatian representatives proposed an attack on Serb-held territory from Livno in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in order to draw off part of the forces besieging Bihać and to prevent its capture by the Serbs. The U.S. officials gave no response to the proposal and Operation Winter '94 was ordered the same day. Besides contributing to the defence of Bihać, the attack advanced positions held by the HV and the HVO nearer to supply routes vital to the RSK.[5]

The meeting was one in a series held in Zagreb and Washington, D.C. following the March 1994 Washington Agreement.[5] The agreement ended the Croat–Bosniak War, re-allied the ARBiH and the HVO against the VRS and provided Croatia with US military advisors from the Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI). MPRI was hired because a UN arms embargo was still in place, ostensibly to prepare the HV for NATO Partnership for Peace programme participation. The organization trained HV officers and personnel for 14 weeks from January to April 1995. It was also speculated that the MPRI also provided doctrinal advice, scenario planning and US government satellite information to Croatia.[7] MPRI and Croatian officials dismissed such speculation.[8][9] In November 1994, the US unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina,[10] in effect allowing the HV to supply itself as arms shipments entered through Croatia.[11] The US involvement reflected a new military strategy endorsed by President Bill Clinton since February 1993.[12]

Call for Croatian intervention

On 17 July, the militaries of the RSK and the VRS started a fresh effort to capture Bihać by expanding on gains made during Operation Spider. The offensive, codenamed Operation Sword '95, aimed to capture Cazin—a transportation route hub, situated in the centre of the ARBiH/HVO-controlled Bihać pocket. The attack was spearheaded by the RSK Special Units Corps and supported by the "Pauk" (Spider) operational group of the Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia (APWB) forces—who had been RSK allies since 1993— advancing from the northwest, with the RSK 39th Banija Corps from the northeast and the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps from the southeast. The effort was also supported by about 500 Yugoslav Army special forces and Željko Ražnatović Arkan's Serb Volunteer Guard—for a total of about 19,000 attacking or sector-holding troops arrayed against the ARBiH 5th Corps. By 21 July, the RSK troops managed a 7-kilometre (4.3 mi) breakthrough, but failed to sever the Bihać–Cazin road. A renewed push by the RSK and APWB troops four days later brought their forces within 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) of Cazin and put them in control or in favourable positions to strike several key passes and dominant points of the battlefield by 26 July. The ARBiH 5th Corps was left in a critical defensive situation, dependent on outside help.[13]

As the situation around Bihać deteriorated for the ARBiH, the government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina realized that it could not hold the area on its own and asked Croatia for military intervention. ARBiH Chief of Staff Rasim Delić appealed to the HV and the HVO to assist the ARBiH 5th Corps on 20 July, proposing HV attacks towards Bosansko Grahovo, Knin and Vojnić. His plea was supported by President of Turkey Süleyman Demirel when he met Croatian President Franjo Tuđman in the Brijuni Islands the next day.[14]

This led to signing of the Split Agreement—a mutual defence agreement—by Tuđman and the President of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Alija Izetbegović in Split on 22 July,[13] permitting large-scale deployments of the HV in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[15] Besides Tuđman and Izetbegović, the agreement was signed by President of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Krešimir Zubak, and the Prime Minister of Bosnia and Herzegovina Haris Silajdžić.[16] It was mediated by Demirel.[17] The agreement specifically stated that Croatia requested urgent military aid, especially for the Bihać area, and that the parties to the agreement intended to coordinate their military activities.[13] The full title of the Split Agreement, or Split Declaration,[18] is Declaration on implementation of the Washington Agreement, joint defence against Serb aggression and achievement of a political solution in accordance with the efforts of the international community (Deklaracija o oživotvorenju Sporazuma iz Washingtona, zajedničkoj obrani od srpske agresije i postizanju političkog rješenja sukladno naporima međunarodne zajednice).[16] The US Ambassador to Croatia, Peter Galbraith, and a German ambassador, representing the European Union,[19] were present at the signing ceremony.[20]

Aftermath

The agreement provided the HV with the opportunity to extend its territorial gains from Operation Winter '94 by advancing from the Livanjsko field. The move was expected to relieve pressure on the ARBiH 5th Corps defending Bihać, while positioning the HV in a more favourable position to strike Knin, the RSK capital.[13] The HV and HVO responded quickly through Operation Summer '95 (Ljeto '95). The offensive, commanded by HV Lieutenant General Ante Gotovina, succeeded in capturing Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč on 28–29 July. The attack drew off some RSK units away from Bihać,[15][21] but not as many as expected at the outset of the operation. Nevertheless, the offensive put the HV in an excellent position,[22] as it isolated Knin from Republika Srpska and FR Yugoslavia, and led to the capture of Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč, which sat astride the only direct route between the two.[23]

Regardless of the limited scope of Operation Summer '95, the Split Agreement became a fundamental instrument to change the overall strategic situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina where Bosnian Serbs had had the upper hand since the beginning of the Bosnian war, as well as in Croatia, where the front lines had been largely static since the 1992 Sarajevo armistice.[22] As Operation Summer '95 concluded, the RSK and Republika Srpska changed their priority from smashing the Bihać pocket to fending off a possible Croatian offensive to capture Knin (advancing from the recently gained territory in Bosnia and Herzegovina). RSK leaders Milan Martić and Mile Mrkšić agreed with UN Special Representative Yasushi Akashi to withdraw from the Bihać area on 30 July, hoping the move would contribute to averting the Croatian attack.[24] Albeit, the attack materialized days later as Operation Storm, a decisive victory to the HV in the Croatian War of Independence.[25]

Success of Operation Storm also represented a strategic victory in the Bosnian War as it lifted the siege of Bihać,[26] and allowed Croatian and Bosnian leaderships to plan a full-scale military intervention in the VRS-held Banja Luka area, based on the Split Agreement—aimed at creating a new balance of power in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a buffer zone along the Croatian border, and contributing to the resolution of the war. In September 1995, the intervention came about as Operation Mistral 2, supported by the ARBiH offensive Operation Sana, combined with a NATO air campaign in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[27] The offensives broke the VRS defences and captured large swathes of territory.[28] The feat was repeated in Operation Southern Move (Operacija Južni potez) carried out in October, advancing within 25 kilometres (16 miles) of Banja Luka,[29] and contributing to the start of peace talks that would result in the Dayton Agreement soon thereafter.[30] Overall, deployment of the HV based on the Split Agreement, proved decisive in the defeat of the VRS in the Bosnian War.[31]

References

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Emma Daly; Andrew Marshall (27 November 1994). "Bihac fears massacre". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Halberstam 2003, pp. 284–286

- Hodge 2006, p. 104

- Vlado Vurušić (9 December 2007). "Krešimir Ćosić: Amerikanci nam nisu dali da branimo Bihać" [Krešimir Ćosić: Americans did not let us defend Bihać]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "Oluja - bitka svih bitaka" [Storm - battle of all the battles]. Hrvatski vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (303/304). July 2010. ISSN 1333-9036.

- Dunigan 2011, pp. 93–94

- Avant 2005, p. 104

- Ankica Barbir-Mladinović (20 August 2010). "Tvrdnje da je MPRI pomagao pripremu 'Oluje' izmišljene" [Claims that the MPRI helped prepare the 'Storm' are fabrications] (in Serbo-Croatian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Bono 2003, p. 107

- Ramet 2006, p. 439

- Woodward 2010, p. 432

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 363–364

- "Slobodan Praljak's submission of the expert report of Dr. Josip Jurčević" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 13 March 2009. p. 149. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, p. 254

- "Deklaracija od 22. srpnja 1995" [Declaration of 22 July 1995] (in Croatian). Office of the President of Croatia. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- "Croat-Bosnian Agreement: Reluctant Allies". Transitions Online. 31 July 1995.

- Bono 2003, p. 114

- "Dobra podloga za nadgradnju" [Good basis for development] (in Serbo-Croatian). Al Jazeera Balkans. 20 November 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Ivo Pukanić (10 June 2003). "Ante Gotovina: "Spreman sam razgovarati s haaškim istražiteljima u Zagrebu"" [Ante Gotovina: "I am ready to talk to ICTY investigators in Zagreb"]. Nacional (weekly) (in Croatian). Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Raymond Bonner (31 July 1995). "Croats Confident As Battle Looms Over Serbian Area". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013.

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 364–366

- Burg & Shoup 2000, p. 348

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 366–367

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 370–376

- Marijan 2007, p. 134

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 374–377

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 379–383

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 390–391

- Kevin Fedarko (11 September 1995). "NATO and the Balkans: Louder than words". Time. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, p. 392

Bibliography

- Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990-1995. Diane Publishing Company. 2003. ISBN 9780756729301. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Avant, Deborah D. (2005). The Market for Force: The Consequences of Privatizing Security. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521615358. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991-1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535337. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bono, Giovanna (2003). Nato's 'Peace Enforcement' Tasks and 'Policy Communities': 1990 - 1999. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754609445. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (2000). The War in Bosnia Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781563243097. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Dunigan, Molly (2011). Victory for Hire: Private Security Companies' Impact on Military Effectiveness. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804774598. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Halberstam, David (2003). War in a Time of Peace: Bush, Clinton and the Generals. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780747563013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Hodge, Carole (2006). Britain And the Balkans: 1991 Until the Present. Routledge. ISBN 9780415298896. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Marijan, Davor (2007). Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian memorial-documentation center of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. ISBN 9789537439088. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918-2006. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253346568. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Woodward, Susan L. (2010). "The Security Council and the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia". In Vaughan Lowe; Adam Roberts; Jennifer Welsh; Dominik Zaum (eds.). The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191614934. Retrieved 29 December 2012.