Water management in Victoria

Water management in Victoria deals with the management of water resources in and by the Australian State of Victoria.

History

Waterworks trusts

Following droughts in the 1870s, the Water Conservation and Distribution Act 1881 was passed to help establish local waterworks trusts. It allowed local trusts to borrow funds from the government for the construction of water supply works. The trusts could then charge water rates to users in order to recoup their costs and pay the interest on the loans.[1]

In 1887, the Mildura Irrigation Company was established as a privately owned water supply company in Mildura. After the collapse of its parent company in 1895, it became a co-operative known as the Mildura Irrigation Trust, which later become known as the First Mildura Irrigation Trust (FMIT). This operated in the Mildura area until 2008 when it was forcibly taken over by the Victorian government.

In December 1889, the shires of Oakleigh, Dandenong, Moorabbin, and Mornington voted for the formation of an urban water trust to bring water from the catchment area of the Dandenong Ranges. Plans were made for "the storage of 596,000,000 cubic feet of water, to supply 39,000 people with water for domestic purposes" to "ensure a permanent and efficient supply". The cost of the scheme was estimated to be £41,000 with the contribution of each shire being Moorabbin £23,247, Oakleigh £11,852, Dandenong £5,000 and Mornington £1,000. Storage tanks were proposed to be constructed for each township to provide for a supply of at least 20,000 gallons.[2]

The State Rivers and Water Supply Commission was created in 1905 by the Water Act 1905 to coordinate and manage the State's rural water resources and eventually to take over all Victorian rural water trusts and irrigation schemes. The Commission was replaced in 1984 by the Rural Water Commission.[3]

The Geelong Municipal Waterworks Trust was created in 1908 and expanded in 1910 to become the Geelong Waterworks and Sewerage Trust. In 1984 the trust was merged with other local water and sewage authorities to form the Geelong and District Water Board, and again restructured to form the Barwon Region Water Authority in 1994 (trading as Barwon Water).[4]

Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works

Melbourne received its first piped water, from the Yan Yean Reservoir, in 1857.[5][6] Water shortages in the late 1870s led to the construction of the Toorourrong scheme in 1882–1885,[7] and the Maroondah Aqueduct in 1886–1891. In 1888 a large part of the upper Yarra valley was reserved for water supply purposes.[8]

In 1891, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) was a public utility board in Melbourne, set up to provide water supply, sewerage and sewage treatment functions for the city, and to create a piped sewerage system.

MMBW's responsibility covered the Yan Yean Reservoir (supplemented by the Toorourrong Scheme), the first stage of the Maroondah Scheme, and six metropolitan service reservoirs.

MMBW continued to augment Melbourne's water supply with diversions from upland tributaries of the Yarra River. The Maroondah Scheme was extended with a pipeline diversion from Coranderrk Creek (1908). A diversion weir on the O'Shannassy River was completed in 1914 and replaced by the O'Shannassy Reservoir in 1928. Maroondah Reservoir was completed in 1927, replacing a diversion weir upstream of the site.

Silvan Reservoir was completed in 1932 to regulate the increased flows in the O'Shannassy Aqueduct from the Upper Yarra River and Coranderrk Creek diversions. Water flowed out of Silvan Reservoir through the Mount Evelyn Aqueduct; the aqueduct was later replaced by pipes but is still visible in places with the Mount Evelyn Aqueduct Walk alongside.

The diversion of water from the Upper Yarra River commenced in 1939 with a weir upstream of the present dam and an aqueduct and pipeline to the O'Shannassy Aqueduct.[5] The Upper Yarra Dam was completed in 1957, increasing Melbourne's total storage capacity to nearly 300,000 megalitres. While the Upper Yarra Project was being built, a 1.7-metre diameter pipeline from a basin near Starvation Creek to Silvan Reservoir was completed in 1953. A duplicate pipeline of the same diameter was completed in 1964.

In response to the severe drought of 1967–68:

- the diversion of Starvation, McMahons, Armstrong and Cement Creeks commenced between 1968 and 1971.

- Greenvale Reservoir, with a capacity of 27,000 megalitres was completed in 1971 to meet the growing need in the western suburbs, especially during summer.

- construction of Cardinia Reservoir was started in 1969 with it being filled to its 287,000-megalitre capacity in 1977, bringing Melbourne's total storage capacity to 610,000 megalitres.

To improve transfer capacity between Upper Yarra and Silvan reservoirs, and to enable water harvested from the Thomson River to be transferred to Cardinia Reservoir, the 2.1-metre diameter Yarra Valley Conduit and Silvan-Cardinia main were built in 1975.

In 1969 work commenced on diverting part of the flow of the Thomson River in Gippsland into the Upper Yarra River catchment. The final stage of the Thomson project concluded in May 1983 with an extension of the Thomson-Yarra Tunnel and completion of the dam wall. Thomson Reservoir has a storage capacity of 1,068,000 megalitres.

The Sugarloaf Reservoir Project, including a major pumping station and water treatment plant, was completed in 1981, increasing Melbourne's total storage capacity by 95,000 megalitres. Sugarloaf uses water pumped from the Yarra River at Yering Gorge and water transferred from Maroondah Reservoir via the Maroondah aqueduct. Sugarloaf is important in meeting peak summer demand in the northern parts of Melbourne.

In 1991, MMBW was merged with a number of smaller urban water authorities to form Melbourne Water.

1990s restructure

Catchment Management Authorities

Ten Catchment Management Authorities (CMAs) that cover the whole of Victoria were established in 1994. Their functions include the production of 5-year regional catchment strategies, which is a statement of how each CMA plans to manage its region over the coming 5 years and is developed with the principles of integrated catchment management. It should cover the condition of the land and water, assess land degradation and prioritise areas for attention, set out a program of works to be undertaken and who will be undertaking the works, specify how the works and land and water condition will be monitored and provide for review of the strategy. The regional catchment strategy can also undertake to provide incentives to landholders, educational programs, research and other services.[9]

Melbourne Water

MMBW was abolished in 1992 and was succeeded by Melbourne Water.

In 2008, Melbourne Water commenced work on the North South Pipeline from northern Victoria's Eildon and Goulburn Valley area to Melbourne.

Another project to avert a water shortage in Melbourne was the Victorian Desalination Plant at Wonthaggi, south-east of Melbourne, which was completed in December 2012. It has an annual capacity of 150 gigalitres. Melbourne Water pays the owner of the plant, even if no water is ordered, $608 million a year,[10] or $1.8 million per day, for 27 years. The total payment is between $18 and $19 billion.[11] On 1 April each year, the Minister for Water places an order for the following financial year, up to 150 gigalitres a year, at an additional cost to Melbourne Water and consumers.[11]

Victoria's water system

Victoria has undertaken several major construction projects to link state water supplies and to establish a statewide water market in preparation for the privatisation of Victoria's water.[12] The works included the Wonthaggi desalination plant built on the South Gippsland coastline at Wonthaggi, which was announced in June 2007, at the height of the crippling millennium drought when Melbourne's water storage levels were at 28.4%, a drop of more than 20% from the previous year. Lawmakers and bureaucrats were suddenly grappling with the frightening prospect that the city could run out of water. The cost of the plant was estimated to be more than $3 billion. The plant was completed in December 2012.[13] Because of the cost of producing water, it is intended to be a backup water source. The merit of the project has been questioned by three reports by the Productivity Commission and the National Water Commission, on the basis of the higher production cost of the plant. The ongoing costs of keeping the plant on standby is $608 million a year.[10]

Several pipelines have also been constructed in an effort to link regional systems to facilitate the trading of water. For example, the North–South Pipeline was completely in February 2010 to carry water from the Goulburn River to Melbourne's Sugarloaf Reservoir in times of need, and an interconnector pipeline connecting the Geelong-Ballarat region.

Pricing of water

In Victoria, the Essential Services Commission (ESC) is responsible for price regulation and setting service standards for water services under Part 1A of the Water Industry Act, the Essential Services Commission Act 2001 and the Water Industry Act’s Water Industry Regulatory Order. The legislative framework provides the ESC with powers and functions to make price determinations, regulate standards and conditions of service and supply, and require regulated businesses to provide information.

Consumer prices for water in and around the Melbourne metropolitan area are determined by the Essential Services Commission and, beginning 1 July 2021, the Commission approved maximum prices for a five-year regulatory period.

Following the Commission's determination, an annual tariff schedule is created for Melbourne Water. The schedule outlines the maximum prices Melbourne Water can charge its retailers for specific services, such as water delivery and sewage processing and the maximum prices it can charge consumers of waterways and drainage services.

Each year in June the Essential Services Commission confirms the prices to apply from 1 July for the 15 water businesses providing urban water and sewerage services to residential customers. They also publish estimates of household bills for water and sewerage.

Since 2016, water pricing has been based on the PREMO incentive mechanism, which focuses on five elements: performance, risk, engagement, management and outcomes. The PREMO framework seeks to link reputation and financial outcomes to the level of ambition in a water business’s price proposal. It also holds water businesses accountable for the actions and decisions they make and for delivering the service outcomes proposed.

Geology and geography

Victoria's northern border follows a straight line from Cape Howe to the start of the Murray River and then follows the Murray River as the remainder of the northern border. On the Murray River, the border is the southern bank of the river, so that none of the water of the Murray belongs to Victoria. The border also rests at the southern end of the Great Dividing Range, which stretches along the east coast and terminates west of Ballarat. It is bordered by South Australia to the west and shares Australia's shortest land border with Tasmania. The official border between Victoria and Tasmania is at 39°12' S, which passes through Boundary Islet in the Bass Strait for 85 metres.[14][15][16]

Victoria contains many topographically, geologically and climatically diverse areas, ranging from the wet, temperate climate of Gippsland in the southeast to the snow-covered Victorian alpine areas which rise to almost 2,000 m (6,600 ft), with Mount Bogong the highest peak at 1,986 m (6,516 ft). There are extensive semi-arid plains to the west and northwest. There is an extensive series of river systems in Victoria. Most notable is the Murray River system. Other rivers include: Ovens River, Goulburn River, Patterson River, King River, Campaspe River, Loddon River, Wimmera River, Elgin River, Barwon River, Thomson River, Snowy River, Latrobe River, Yarra River, Maribyrnong River, Mitta River, Hopkins River, Merri River and Kiewa River. The state symbols include the pink heath (state flower), Leadbeater's possum (state animal) and the helmeted honeyeater (state bird).

The state's capital, Melbourne, contains about 70% of the state's population and dominates its economy, media, and culture. For other cities and towns, see list of localities (Victoria) and local government areas of Victoria.

Climate

Victoria has a varied climate despite its small size. It ranges from semi-arid temperate with hot summers in the north-west, to temperate and cool along the coast. Victoria's main land feature, the Great Dividing Range, produces a cooler, mountain climate in the centre of the state. Winters along the coast of the state, particularly around Melbourne, are relatively mild (see chart at right).

Victoria's southernmost position on the Australian mainland means it is cooler and wetter than other mainland states and territories. The coastal plain south of the Great Dividing Range has Victoria's mildest climate. Air from the Southern Ocean helps reduce the heat of summer and the cold of winter. Melbourne and other large cities are located in this temperate region. The autumn months of April/May are mild and bring some of Australia's colourful foliage across many parts of the state.

The Mallee and upper Wimmera are Victoria's warmest regions with hot winds blowing from nearby semi-deserts. Average temperatures exceed 32 °C (90 °F) during summer and 15 °C (59 °F) in winter. Except at cool mountain elevations, the inland monthly temperatures are 2–7 °C (4–13 °F) warmer than around Melbourne (see chart). Victoria's highest maximum temperature of 48.8 °C (119.8 °F) was recorded in Hopetoun on 7 February 2009, during the 2009 southeastern Australia heat wave.[17]

The Victorian Alps in the northeast are the coldest part of Victoria. The Alps are part of the Great Dividing Range mountain system extending east–west through the centre of Victoria. Average temperatures are less than 9 °C (48 °F) in winter and below 0 °C (32 °F) in the highest parts of the ranges. The state's lowest minimum temperature of −11.7 °C (10.9 °F) was recorded at Omeo on 15 June 1965, and again at Falls Creek on 3 July 1970.[17] Temperature extremes for the state are listed in the table below:

Rainfall

Victoria is the wettest Australian state after Tasmania. Rainfall in Victoria increases from south to the northeast, with higher averages in areas of high altitude. Mean annual rainfall exceeds 1,800 millimetres (71 inches) in some parts of the northeast but is less than 280 mm (11 in) in the Mallee.

Rain is heaviest in the Otway Ranges and Gippsland in southern Victoria and in the mountainous northeast. Snow generally falls only in the mountains and hills in the centre of the state. Rain falls most frequently in winter, but summer precipitation is heavier. Rainfall is most reliable in Gippsland and the Western District, making them both leading farming areas. Victoria's highest recorded daily rainfall was 377.8 mm (14.87 in) at Tidal River in Wilsons Promontory National Park on 23 March 2011.[17]

- Average temperatures and precipitation for Victoria

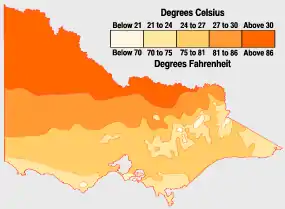

Average January maximum temperatures:

Average January maximum temperatures:

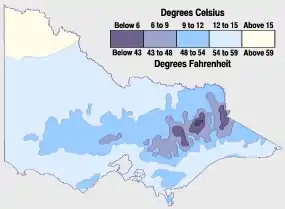

Victoria's north is almost always hotter than coastal and mountainous areas. Average July maximum temperatures:

Average July maximum temperatures:

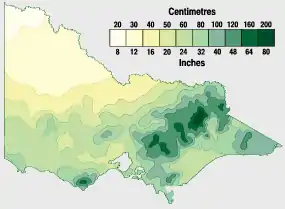

Victoria's hills and ranges are coolest during winter. Snow also falls there. Average yearly precipitation:

Average yearly precipitation:

Victoria's rainfall is concentrated in the mountainous north-east and coast.

See also

References

- "Victorian Water Supply Heritage Study Volume 1: Thematic Environmental History Final Report" (PDF). www.heritage.vic.gov.au/. 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- "OUR NEWS SUMMARY". Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954). 1889-12-21. p. 14. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- State Rivers and Water Supply Commission

- "Geelong Waterworks and Sewerage Trust". Public Record Office Victoria online catalogue. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- Ritchie, E. G. (October 1934), "Melbourne's Water Supply Undertaking" (PDF), Journal of Institution of Engineers Australia, 6: 379–382, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-18

- Gibbs, George Arthur (1915), Water supply systems of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works / compiled from official documents by George A. Gibbs, Melbourne: D. W. Paterson

- "Melbourne Water Supply", The Argus, p. 5, 1888-01-17, retrieved 2011-04-23

- "Melbourne Water Supply - Important Additions to the Watershed Areas", The Argus, p. 11, 1888-05-31, retrieved 2011-07-21

- Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, s.12, page 49. Victorian Government, 2007.

- "Subscribe to the Herald Sun". www.heraldsun.com.au. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- "Victorians pay dearly, but not a drop to drink". ABC News. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- D!ssent, Article by Kenneth Davidson "Water Lies", Issue 31 Summer 09/10

- Desalination Plant : Projects. Melbourne Water. Retrieved on 20 January 2009

- "Victoria Tasmania border". Archived from the original on 2 January 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2006.

- "Boundary Islet on". Street-directory.com.au. 4 December 1999. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Moore, Garry (April 2014). "The boundary between Tasmania and Victoria: Uncertainties and their possible resolution" (PDF). Traverse. The Institute of Surveyors Victoria (294). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "Rainfall and Temperature Records: National" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 8 June 2018.