Water resources management in Guatemala

Guatemala faces substantial resource and institutional challenges in successfully managing its national water resources. Deforestation is increasing as the global demand for timber exerts pressure on the forests of Guatemala. Soil erosion, runoff, and sedimentation of surface water is a result of deforestation from development of urban centers, agriculture needs, and conflicting land and water use planning. Sectors within industry are also growing and the prevalence of untreated effluents entering waterways and aquifers has grown alongside.

| Water resources management in Guatemala[1] | |

|---|---|

| Withdrawals by sector 2000 |

|

| Renewable water resources | 111 km3 |

| Surface water produced internally | 102.8 km3 |

| Groundwater recharge | 33.7 km3 |

| Overlap shared by surface water and groundwater | 25.2 km3 |

| Renewable water resources per capita | 7,979 m3/year |

| Wetland designated as Ramsar sites | 6,285 km2 |

| Hydropower generation | 47% |

Untreated wastewater contaminates water resources as well where treatment facilities are inadequate. Populations are unequally distributed and this creates challenges of conveyance. In a mountainous country this can easily be mitigated with gravity fed systems. Where water pumps are needed, water delivery is much more expensive and can be a barrier to consistent access.

Guatemala is also facing institutional challenges, mostly due to a lack of coordination among the different agencies responsible for water resources management where duplication of efforts and responsibility gaps exist. SEGEPLAN and the Secretaria de Recursos Hidraulicos de la Presidencia are other ministry level institutions that highlight possible overlaps in duties as both are within the office of the president and have water resources management responsibilities.

Guatemala has ample amounts of rainwater, surface and groundwater. While surface water is abundant, they are seasonal and often polluted. Groundwater from wells and springs is important to the national supply resource meeting demands for potable water for public and domestic needs. Groundwater is also used for the agricultural and industrial sectors as well. Hydroelectricity output is the key component (92%) of Guatemala's electricity generation and is highlighted by the Chixoy hydroelectric project. The National Institute of Electricity (INDE) (El Instituto Nacional de Electrificacion) oversees and implements hydroelectric projects in Guatemala.

Water resources management challenges

Management of water resources in Guatemala is shared by several government agencies and institutions. Most of these agencies conduct their work with little or no coordination with other agencies, which creates duplication of work and inefficient use of resources.[2] In addition, there is a need for the enactment of watershed management plans aimed at integrating different water uses, controlling deforestation and water quality.

Water resources in Guatemala are also stressed by domestic users. Generally, populations are larger in regions where water availability is low due to altitude or rainfall deficit, and the opposite is true in regions where water resources are abundant. Guatemala City is a prime example. The city is home to more than 20% (3.2 million) of the countries population. However, the valley where Guatemala City is located is in a south central region of the country and spans the Continental Divide. The location of Guatemala city near the continental divide is at the origin of all nearby rivers where flows are minimal. This equates to small quantities of surface water and inadequate groundwater sources that cannot fully supplement the needs of the city.[2]

Water resource base

The hydrographic system is divided into three primary drainage basins. First, the Pacific Ocean drainage basin covers 22% of the country and counts 18 watersheds. Some of the rivers in this zone transport volcanic sediments to be deposited along the coast and contributes to coastal flooding due to reduced depths of tidal marshes. Annual surface runoff in this basin is 25.5 km3. The Caribbean Sea drainage basin covers 31% of the country and has 10 watersheds. Average annual surface runoff in this basin is calculated at 31.9 km3. The Gulf of Mexico basin covers 47% of Guatemala and 10 watersheds. The rivers in this basin have the largest flows in the country and drain towards Mexico. Surface runoff in this basin is 43.3 km3.[3]

Guatemala, as its (Mayan) name indicates, is a land of forests. The country is also mountainous and rainfall is influenced by Pacific and Atlantic ocean weather patterns such as El Niño, La Niña, and hurricanes. The Caribbean Sea influences rainfall patterns in Guatemala in the same way. Average rainfall varies from 700 mm per year in the eastern regions of the country to around 1,000 mm in the central regions, and 5,000 mm of rainfall in the northeastern regions. The current population in the mountainous northwestern zone numbers around five million inhabitants and this region has high levels of rainfall (up to 4,000 mm per year) and steep slopes that are susceptible to erosion. This region is an area with great water potential, but also subject to irreversible damage from soil loss and the alteration of the water cycle.[4]

Surface water and Groundwater resources

Surface water covers about 1,000 km2 of the 108,900 km2 of land area across Guatemala. Although surface water resources are abundant, they are unequally distributed, highly seasonal, and generally polluted.[2] Fresh ground water from wells and springs is an essential resource and a major source of potable water and used for agricultural, industrial, public, and domestic demand. Ground water is generally plentiful from sedimentary aquifers throughout the plains, valleys, and lowlands of the country.[2]

The two most substantial aquifers are the Pacific Coastal Plain alluvium and the karstic and fractured limestone that extend beneath the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, Sierra de Chama, and Peten Lowlands. Other more limited aquifers are important for small-scale local demands. The mountains and hills of Guatemala contain many other types of aquifers, including volcanic pyroclastic and lava deposits, low permeability sediments, igneous, and metamorphic aquifers. Alluvial plains, valleys and lowlands make up about 50% of the countries territory and contain about 70% of the available ground water reserves.[2]

Major lakes & reservoirs

Guatemala has 23 major lakes and another 119 that all encompass an area of 950 km2. Storage capacity for up to half of the lakes in Guatemala is used solely for hydroelectric energy generation and the volume of water is on the order of 524 million m3. The Chixoy Hydroelectric Dam is the largest of the hydroelectric reservoirs with an effective capacity of 275 MW which supplies 15% of the countries electricity demand.[3]

An important lake to highlight located near Guatemala City is the once pristine Lake Amatitlán which is now long degraded from years of domestic and industrial dumping, and deforestation. Each year large quantities of untreated sewage, industrial effluent and around 500,000 tons of sediment are carried into Lake Amatitlán through the lake's primary inflow source, the Villalobos River, causing high levels of water pollution and an accelerated rate of eutrophication and siltation.[5]

The lake is drained by the Michatoya River which is a tributary of the María Linda River and the town of Amatitlán is located at the head of the Michatoya river. A dam with a railway on top was constructed at the narrowest point, thus effectively dividing the lake into two water bodies with different physical, chemical and biological characteristics. The lake is used as a water source for navigation and transportation, sightseeing and tourism, recreation, and fisheries.[6]

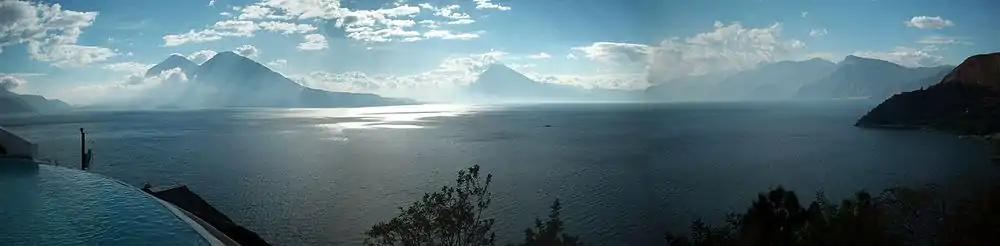

The Lake Atitlán basin is a closed watershed or endorheic lake located in the volcanic highlands of Guatemala. This lake is the deepest lake in Central America with estimated depths of at least 340 meters, however much of the lake has not been completely sounded for depth therefore accurate capacity is not well understood. Competing uses place high demand on the waters of Lake Atitlán and serious problems of water pollution, soil erosion, and forest loss are prevalent. In 1996 the Authority for the Sustainable Management of the Atitlán Basin (AMSCLAE) was established which produced a Master Plan in 2000. However, the plan is still under revision and only a few measures are actually being implemented.

Water quality and pollution

Based on established biological and chemical standards, every water body in Guatemala is considered to be moderately if not critically contaminated. Upper aquifers in major urban areas are contaminated from a variety of sources. In Guatemala City, untreated storm water is injected into the upper aquifer in an attempt to recharge the water supply of the city. Leaching from the landfill in Guatemala City has also severely contaminated the local aquifers and generally, only deep confined aquifers should be considered safe from biological and chemical contamination.[2]

Sewage from Guatemala City has caused the Villalobos and Las Vacas Rivers to be considered the most contaminated streams in the country. Additionally, biological contamination of shallow aquifers by pathogens due to the improper disposal of human or animal wastes is a problem in many populated and rural areas of the country. In agricultural areas, pesticides are a primary source of contamination. Chemical contamination results from the use of fertilizers and pesticides in the sugarcane and banana plantations of the Pacific and Caribbean coastal plains. Along both coasts are streams, marshes, and swamps that contain large quantities of brackish or saline water and unless desalinated, these sources are unsuitable for most uses.[2]

Water resources management by sector

Water coverage and usage

Potable water demand in Guatemala is primarily met with surface water. In urban areas, 70% of their water is surface water while the figure rises to 90% in rural areas. The rest of the water needs are met with groundwater. Out of 329 municipalities, 66% of the water systems utilize gravity to deliver water, another 19% of the systems use pumps and about 15% of the systems use both gravity and pumps. Total annual demand in 2010 is about 835 million m3. About 95% of the total population has potable water coverage. Of this figure, only 75% actually have a house connections while the remainder will carry water from nearby wells, rivers, and other sources.[3]

Water supply and sanitation

Information below taken from: Water supply and sanitation in Guatemala

According to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, access to water and sanitation services has slowly risen over the years in Guatemala. In 1990, 79% of the total population had access to improved water sources, while in 2004, 95% of the population had access. Sanitation coverage has also risen, from 58% of the total population having access to adequate sanitation in 1990, to 86% with access in 2004. The government of Guatemala estimates that the population without access to water services is growing at a rate of at least 100,000 people every year.[7]

Irrigation and drainage

For more information see: Historical background of Irrigation in Guatemala

Irrigation in Guatemala is concentrated in three regions of the country. The Atlantic coast region has low humidity and high evapotranspiration so irrigation is needed for the cultivation of bananas, tomatoes, watermelon, and tobacco. The high plains region has very little rain for much of the year and with fertile volcanic soils that do not retain moisture very well. Without irrigation, there is only one harvest per year so crops such as basic grains require irrigation. The lower coastal zones have irrigated sugarcane and banana plantations.[3]

Irrigation in Guatemala is divided into three key types: i) private irrigation that is normally controlled by a family, company, or community agriculture system. Many of the private plantations are irrigated with gravity water systems; ii) state owned and operated irrigation programs and; iii) small-scale communal irrigation systems which normally are very efficient.[3]

The operation and maintenance of state run irrigation systems is paid for with fees based on surface area irrigated and not by how much water is used. Generally, the collected fees do not cover the real costs of energy needed to irrigate the land. There is a more recent fee aimed at covering this difference that includes an annual payment for a period of 40 years whereby the state will recuperate about 60% of the money invested on projects.[3]

The Master Plan for Irrigation and Drainage (Plan de Accion para la Modernizacion y Fomento de la Agricultura Bajo Riego) (PLAMAR) is effectively the technical division of irrigation and drainage under the Ministry of Agriculture. Furthermore, PLAMAR is the national action plan for the modernization and promotion of lands under irrigation while promoting and coordinating irrigation projects.[8] PLAMAR identified 209,419 ha's under cultivation that had drainage problems; however, regions under irrigation (169,302 ha) did not show evidence of drainage nor salinity problems. The lack of adequate infrastructure to quickly drain large amounts of water has caused flooding problems in the southern coastal regions.[3]

Hydropower

Beginning in the 1970s, Guatemala became heavily invested on hydropower with the construction of large hydroelectric dams. The Chixoy hydroelectric project provides about 15% of the country's power. As of 2013, hydropower accounted for 47% of Guatemala's total electricity generation, with oil, diesel and biomass-fired plants accounting for the rest.[9] The National Institute of Electricity (INDE) (El Instituto Nacional de Electrificacion) encouraged the private sector to build over 1,000 megawatts (MW) of new hydropower in Guatemala. Additionally, INDE constructed the following projects: 340MW Chulac, 130MW Xalala, 135-MW Serchil, 69MW Oregano, 60MW Santa Maria II, 59MW Camotan, and the 23MW El Palmar.[10] In 2008, Guatemala was either planning or constructing about 25 hydroelectricity plants throughout Guatemala totaling approximately 2500 MW.[11]

Legal and institutional framework

Ministries

- SEGEPLAN (Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia) is the presidents planning and programming office. Water resources are a focus of this office. SEGEPLAN elaborates diagnostic information of water and formulates tools for planning the integrated management of water resources. This takes into account prior efforts with the objective of coordinating, complementing, and assuring that governmental efforts favor the proper management of water resources.[12]

- The Secretaria de Recursos Hidraulicos de la Presidencia de la Republica was established in 1992 in response to droughts resulting from El Nino. The aims of the agency were to establish a coherent policy for water resources, to formulate and develop the national hydraulic plan, to coordinate the planning and construction of hydraulic facilities for public use, and to evaluate and approve plans, programs, and projects relating to the use of national resources. The agency also represented the state for the international organizations specializing in national resources to coordinate studies, strategies, or projects of social benefits.[2]

Service Providers

- EMPAGUA (Empresa Municipal de Agua) is the municipal management of Guatemala City’s water authority, responsible for water administration of the growing metropolitan population, and for rain and sanitary sewerage, and sanitation.[13]

- INFOM (Instituto de Fomento Municipal) is the Institute of Municipal Development and is in charge of water sector policies and strategies for implementation, as well as coordination of technical and financial assistance with other institutions that execute drinking water and sanitation programs and projects.[14]

- AMSA (Autoridad para el Manejo Sostenible de la Cuenca y del Lago de Amatitlan) is the authority for the sustainable development of the Amatitlan lake and watershed.[15]

Research Institutes

- INSIVUMEH (Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hidrologia) is the National Institute of seismology, volcanology, hydrology, and weather. This government agency is responsible for conducting research and development in flood control efforts.[16]

Cooperation with El Salvador and Honduras

The upper watershed of the Lempa River is shared by Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, as outlined in the Trifinio Plan, which was established and signed by the aforementioned countries to address economic and environmental problems in the Lempa River basin, and foster cooperation and regional integration. The Trifinio plan or treaty sought to provide a more viable and effective alternative to unilateral development thereby concentrating on greater multinational integration.[17]

The Trifinio region covers an area of about 7,500 km2 in the border areas of Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. The region is made up of 45 municipalities whereby 22 belong to Honduras within the departments of Ocotepeque and Copán, 15 are situated in Guatemala corresponding to the departments of Chiquimula and Jutiapa, and 8 are in the departments of Santa Ana and Chalatenango in El Salvador.[18]

In the early stages of the Trifinio Plan’s development the commission studied three international river basins. In 1987 they developed a new plan involving the Lempa River Basin, the Ulúa River, and the Motagua River. The Motagua and Ulúa rivers were eventually dropped, leaving the Lempa River as the Trifinio Plan’s primary focus.[17]

Multi-lateral assistance

The Central American Water Resource Management Network (CARA) was initiated in 1999 with the backing of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to build capacity in hydrogeology and water resource management throughout the Central America region. The emphasis is on groundwater reflecting a greater than 80% dependence on groundwater for water supply throughout the Central American region. Member countries include Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Bolivia with additional support from Canada and Mexico.[19]

The World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) in collaboration with local partners, is developing a water fund to finance responsible watershed management in Guatemala’s Sierra de las Minas Biosphere. Known as the 'water fund', water users which include bottling companies, distilleries, hydroelectric plants, and paper processing mills are showing their awareness that water is a strategic resource whose conservation must be planned for the long term, by making significant financial contributions towards environmental services in the region. The fund is meant to encourage short-term investments to optimize industrial water use as a means of reducing effluents to the Motagua and Polochic Rivers.[20]

The World Bank is implementing the $85 million project aimed at improving the capacity of the country to respond to and recover from flooding caused by tropical storms and hurricanes. The project is scheduled to conclude in 2012. The development objective of the Catastrophe Development Policy Loan Deferred Draw Down Option Project for Guatemala is to enhance the Government's capacity to implement its disaster risk management program for natural disasters. This objective will be achieved by supporting policy and institutional reform in the following aspects of disaster risk management: i) improving risk identification and monitoring; ii) increasing disaster risk reduction investments; iii) strengthening institutions and planning capacity for risk management; and iv) developing risk financing strategies.[21]

The Inter-American Development Bank has three ongoing projects under implementation and many more that have been completed since 1961. One particular project underway focuses on improving access to potable water for rural communities. The $50 million project was designed to benefit at least 500,000 new rural consumers. Families will have easier access to safe drinking water, which will improve their health and save them time and effort spent on carrying water from remote sources. The program finances the construction of water and sanitation systems for individual communities or groups of communities with an average of 900 people. Each community will make all key decisions related to their respective projects, selecting the system that best suits their needs and capacity. Autonomous water associations were established by the residents of each village and serve to manage the services, and cover operation and maintenance costs by collecting tariffs from users.[22]

UNICEF supports water and sanitation projects, and typically implements short–term projects, including systems with pipelines less than 3 kilometers, manual pumps and school sanitation in very vulnerable communities of four municipalities of Huehuetenango, two municipalities of Quiché, and two in Chiquimula. UNICEF emphasizes the technical strengthening of municipal governments and advocacy to influence the government to assign greater funding for water and sanitation.[23]

Non-Governmental Organizations:

- Catholic Relief Services (CRS): Its water and sanitation component supports integrated interventions based on the national basic model for water and sanitation. CRS has a presence in the following departments: San Marcos Totonicapán, Sololá and Chiquimula.

- Project Concern International (PCI): PCI carries out projects in water and sanitation under its food security program, with financial support from USAID and Breed Love. PCI has a presence in the departments of Huehuetenango and Chiquimula.

- CARE: Until 2006, CARE implemented water and sanitation projects in the southern part of Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Sololá, Quiché and Alta Verapaz. Most of its funding for water and sanitation comes from USAID’s food security program. CARE is still supporting the rehabilitation of water systems and sanitation in the departments of San Marcos and Sololá from Hurricane Stan with a diverse funding base.

Bi-lateral assistance:

- Spanish Government

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

- Japanese Agency of International Cooperation (JICA)

- Swedish Agency for International Development (SIDA/ASDI)

- Dutch Cooperation Agency (SNV)

- European Union (EU)

Importance of wetland sites in Guatemala

Wetlands are key areas for their ability to consistently supply drinking water, treatment of wastewater by natural anaerobic and aerobic processes, offering water and fertile soils for agriculture and food production, absorbing floods after heavy rainfall and tidal surges during oceanic storms, and water storage in periods of droughts. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands came into force in Guatemala October 26, 1990. Guatemala presently has 7 sites designated as Wetlands of International Importance, with a surface area of 628,592 hectares.[24]

- Eco-región Luchuá, Alta Verapaz: 53,523 ha

- Manchón-Guamuchal: 13,500 ha

- Parque Nacional Laguna del Tigre MR: 335,080 ha

- Parque Nacional Yaxhá-Nakum-Naranjo: 37,160 ha

- Punta de Manabique, Izabal: 132,900 ha

- Refugio de Vida Silvestre Bocas del Polochic Izabal: 21,227 ha

- Reserva de Usos Múltiples Río Sarstún Izabal: 35,202 ha

(Source: Ramsar 2009)

References

- FAO Aquastat 1988-2008

- Spillman T.R.; Waite L.; Buckalew J.; Alas H.; Webster T.C. (2000). "WATER RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF GUATEMALA" (PDF). US Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- FAO (2000). "Country profile: Guatemala". FAO. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- Barrientos C.; Fernandez V.H. (1998). "CASE STUDY: GUATEMALA Water, Population, and Sanitation in the Mayan Biosphere Reserve of Guatemala". IUCN. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- Global Nature Fund. "Lake Amatitlan - Guatemala". Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- Reyna, Evelyn Irene. "Integrated Management of the Lake Amatitlan Basin: Authority for the Sustainable Management of Lake Amatitlan and its Basin". Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- Inter-American Development Bank. 2003. Guatemala Rural Water and Sanitation Program (GU-0150) Loan Proposal.

- The World Bank (2009). "GUATEMALA: Country Note on Climate Change Aspects in Agriculture" (PDF). The World Bank. p. 4. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- "International Energy Statistics: Guatemala". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- U.S. Department of Energy. "Ah Guatemala". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- Invest in Guatemala (2008). "Electric Energy Sector". Invest in Guatemala. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- SEGEPLAN (2010). "Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia" (in Spanish). SEGEPLAN. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- EMPAGUA (2010). "Empresa Municipal de Agua" (in Spanish). EMPAGUA. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- INFOM (2010). "Instituto de Fomento Municipal" (in Spanish). INFOM. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- AMSA (2010). "Autoridad para el Manejo Sostenible de la Cuenca y del Lago de Amatitlan" (in Spanish). AMSA. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- INSIVUMEH (2010). "Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia e Hidrologia" (in Spanish). INSIVUMEH. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- López A. (2004). "Environmental Conflicts and Regional Cooperation in the Lempa River Basin The Role of Central America´s Plan Trifinio" (PDF). The Environmental Change and Security Project (ECSP) Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. pp. 13–15. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- Artiga R. (2003). "Water Conflict and Cooperation/Lempa River Basin". UNESCO. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- Bethune D. (2008). "Capacity Building for Integrated Water Resources Management". Central American Water Resource Management Network. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Morales C. (2005). "Water fund finances responsible watershed management in Guatemala". WWF. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- The World Bank (2009). "Catastrophe Development Policy Loan Deferred Draw Down Option Project". The World Bank. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- The Inter American Development Bank (2003). "Rural Water Investment Program". The Inter American Development Bank. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Water For People (2008). "Water For People: Guatemala Country Strategy - 2008-2011" (PDF). Water For People. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- Ramsar (2010). "Ramsar in Guatemala". Retrieved April 29, 2010.