Waverly B. Woodson Jr.

Waverly Bernard Woodson Jr. (August 3, 1922 – August 12, 2005) was an American staff sergeant and health professional. He is best known for his heroic actions as a combat medic during the Battle of Normandy in World War II.

Waverly Bernard Woodson Jr. | |

|---|---|

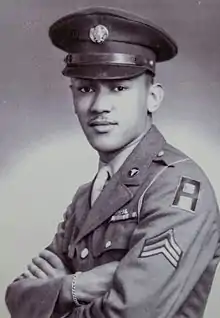

Woodson's official US Army portrait, taken while he held the rank of sergeant. | |

| Nickname(s) | Woody |

| Born | August 3, 1922 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 12, 2005 (aged 83) Gaithersburg, Maryland, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1942–1952 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

| Alma mater | Lincoln University |

| Spouse(s) |

Joann Katharyne Snowden

(m. 1952) |

| Children | 3 |

Life and military service

Waverly Bernard Woodson Jr. was born on August 3, 1922, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After graduating from Overbrook High School, he began studying at Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania,[1] where he was a pre-med student.[2]

After the entry of the United States into World War II, Woodson - then in his second year - put his studies on hold, enlisting in the United States Army on December 15, 1942, alongside his younger brother Eugene.[3][4] After scoring highly on an aptitude test, he joined the Anti-Aircraft Artillery Officer Candidate School, where he was one of only two African Americans. Before completing the course, Woodson was informed that he would not be able to be billeted in the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps due to his race.[4][5][6] As a result, he was trained as a combat medic and assigned to the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion.[7] Woodson underwent training at Camp Tyson, the United States' barrage balloon training center in Paris, Tennessee, where he experienced segregation and discrimination.[8][9] By the time of Operation Overlord, he held the rank of corporal.[10][11][12]

On June 6, 1944, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion participated in the Battle of Normandy as part of the First United States Army; it was the only African American battalion to participate.[13] Woodson was assigned to a landing craft tank (LCT) that was to land at Normandy in the early morning.[14] While coming ashore at Omaha Beach as part of the third wave, Woodson's LCT hit a naval mine[7][15][16] and lost power, drifting ashore with the tide.[17] While drifting, the LCT was hit by an "eighty-eight" shell and Woodson suffered shrapnel injuries to his groin, inner thigh, and back.[3][10][14][18] Upon reaching the shore and having his wounds treated, Woodson and other medics set up a field dressing station under a rocky embankment and began treating other wounded soldiers.[7][19] Woodson worked continuously from 10:00 AM until 4:00 PM on the following day.[20][21] During the 30 hours, he carried out procedures including setting limbs, removing bullets, amputating a foot, and dispensing plasma.[22][23] After being relieved, Woodson was collecting bedding when he was alerted to three British soldiers having been submerged while leaving their LCT; Woodson provided artificial respiration to the three men, reviving them. Woodson was subsequently hospitalized due to his wounds;[20][24] after three days on a hospital ship he requested to return to the front.[2] It has been estimated that Woodson's actions saved the lives of as many as 200 soldiers,[25] both black and white.[5] Woodson's commanding officer recommended him for a Distinguished Service Cross for his actions, but the office of general John C. H. Lee determined that Woodson's actions warranted the greater honor of a Medal of Honor.[10][26] United States Department of War special assistant to the director Philleo Nash proposed that President Franklin D. Roosevelt should give Woodson an award personally.[27][28] Woodson ultimately received a Bronze Star Medal along with a Purple Heart.[2][12][13][29][30] The Philadelphia Tribune wrote, "the feeling is prevalent among Negroes that had Woodson been of another race the highest honor [a Medal of Honor] would have been granted him."[31]

Shortly after the Battle of Normandy, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion was redeployed to the United States, where it served on bases in Georgia followed by Hawaii.[23] Upon the end of World War II in 1945, Woodson was moved to the United States Army Reserve.[32] He initially hoped to study medicine, but was unable to find a medical school that would admit him as an African American.[33] He went on to complete his studies at Lincoln University,[34] graduating in 1950 with a degree in biology. Woodson was reactivated by the Army upon the outbreak of the Korean War that same year.[2] He was initially assigned to train combat medics at Fort Benning in Georgia before being reassigned to running an Army morgue.[24][33] He served in the United Kingdom, France, and the Asia-Pacific. Within the United States, he also served at Fort Meade, Valley Forge General Hospital, the Communicable Disease Center, and Walter Reed Army Medical Center.[7] Woodson left the Army in 1952 with a final rank of staff sergeant.[35]

Woodson married Joann Katharyne Snowden in 1952; the couple had two daughters and a son.[2][23]

After leaving the Army,[32] Woodson went on to work in the Bacteriology Department of the National Naval Medical Center. In 1959, he began working in the Clinical Pathology Department of the National Institutes of Health where he supervised the staffing and operation of operating theaters until retiring in 1980.[7][23]

In 1994, Woodson was one of three veterans invited to visit Normandy by the Government of France to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the D-Day landings.[35] He was presented with a commemorative medallion.[23][24]

Woodson died on August 12, 2005, in the Wilson Health Care Center in Gaithersburg, Maryland at the age of 83. He was buried with military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.[36] His papers were donated to his alma mater, Lincoln University.[37]

Awards and decorations

Woodson received the following awards and decorations:

- American Campaign Medal[1]

- Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medal[1]

- Bronze Star Medal[1]

- European–African–Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with Arrowhead device and two Bronze Stars[1]

- Good Conduct Medal[1]

- Korean Service Medal[1]

- National Defense Service Medal[1]

- Purple Heart[1]

- United Nations Medal[1]

- World War II Victory Medal[1]

Legacy

Despite his acknowledged heroism,[38] Woodson did not receive the Medal of Honor.[29][39] This has been attributed to racial discrimination and to the National Personnel Records Center fire in 1973 that destroyed around 80% of the Army's personnel records.[40] In September 2020, United States Senator Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) introduced bill S.4535: "A bill to authorize the President to award the Medal of Honor to Waverly B. Woodson, Jr., for acts of valor during World War II".[41] An equivalent bill, H.R.8194, was also introduced in the United States House of Representatives by David Trone (R-Md.).[42] Woodson's widow Joann has announced that, if Woodson was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, she would donate it to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.[40] In June 2021, Commanding General of the First United States Army Thomas S. James Jr. wrote in favor of Woodson receiving the Medal of Honor.[33]

In April 2022, the Rock Island Arsenal Health Clinic in Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois was renamed the Woodson Health Clinic in honor of Woodson. Woodson's son Stephen attended a ceremony to mark the renaming where he unveiled a portrait of Woodson.[24]

Author Alan Gratz based the character Henry Allen in his 2019 novel Allies on Woodson.[5]

References

- "Waverly Woodson". The Frederick News-Post (via Legacy.com). August 30, 2005. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Fikes, Robert (October 7, 2017). "Waverley Bernard Woodson Jr. (1922-2005)". BlackPast.org. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- Noble, Michael (2019). D-Day: Untold stories of the Normandy Landings inspired by 20 real-life people. Wide Eyed Editions. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-78603-627-8.

- Hervieux, Linda (2016). Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes. Amberley Publishing. pp. 157–159. ISBN 978-1-4456-6349-4.

- Gratz, Alan (2019). Allies. Scholastic Corporation. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-338-24574-5.

- "Waverly Bernard Woodson, Jr". National Park Service. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- "Waverly Bernard "Woody" Woodson, Jr. - served as a U.S. Army combat medic on Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944" (PDF). Montgomery County. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- U.S. News & World Report. Vol. 120. 1996. p. 36.

- Parkinson, Robert (March 1, 2018). "Camp Tyson". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Rempfer, Kyle (July 3, 2019). "Lawmakers want this African-American soldier to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor for actions on D-Day". Army Times. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Furr, Arthur (1947). Democracy's Negroes. House of Edinboro. p. 87.

- This is Our War: Selected Stories of Six War Correspondents who Were Sent Overseas by the Afro-American Newspapers: Baltimore, Washington, Philadelphia, Richmond and Newark. Afro-American Company. 1945. p. 30.

- Choker, Michael D. (2013). "320th Anti-Aircraft Balloon Battalion". In Bielakowski, Alexander M. (ed.). Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. ABC-Clio. p. 591. ISBN 978-1-59884-428-3.

- Snibbe, Kurt (June 5, 2021). "A Black soldier's valor in the D-Day landing may have been under recognized". Orange County Register. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- Booker, Bryan D. (2008). African Americans in the United States Army in World War II. McFarland & Company. p. 91-92. ISBN 978-0-7864-3195-3.

- MacGregor, Morris J.; Nalty, Bernard C., eds. (1977). Blacks in the Armed Forces. Vol. 7. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-8420-2115-9.

- Bowman, Martin W. (2013). Bloody Beaches. Pen and Sword Books. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-4738-2679-3.

- Thompson, William (June 5, 1994). "A day of courage and death seared into the memories of all who fought there". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Newman, Paul L. (June 6, 2022). "Remembering the D-Day heroism of a Black soldier from Philadelphia". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 6, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- United States Congress (1946). Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 78th Congress, second session. Vol. 92. United States Government Printing Office. pp. A435–A436.

- Knowlton, Brian (June 5, 2009). "Forgotten battalion's last returns to beachhead". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Ryan, Kate (July 15, 2019). "Push continues to get Medal of Honor to 'Forgotten Hero' of World War II". Congressional Black Caucus. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Greenspan, Jesse (June 4, 2019). "A black medic saved hundreds on D-Day. Was he deprived of a Medal of Honor?". History.com. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Connor, Jon Micheal (April 20, 2022). "Ceremony marks new name for RIA Health Clinic to Woodson Health Clinic, honoring World War II combat medic". Army.mil. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- Chambless, J. (March 13, 2015). "Lincoln University honors a World War II hero". Chester County Press. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Dixon, Randy (August 26, 1944). "Four Heroes". Pittsburgh Courier (via Newspapers.com). p. 1. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

Four Negro medics, lone survivors of a shipload of D-Day assaulters and the only medics who got through alive in their sections of the beaches of Normandy, were recommended this week for high decorations by their commanding general. [...] Cpl. Waverly Woodson, Jr., Philadelphia, Pa., medical technician.

- Hervieux, Linda (November 11, 2016). "Remember D-Day's African-American soldiers on Veterans Day". NBC News. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Meek, James Gordon; Hosenball, Alex (November 11, 2015). "'Negro' D-Day hero overlooked for Medal of Honor". ABC News. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- Bullinger, Jonathan M. (2019). Reagan's "Boys" and the Children of the Greatest Generation: U.S. World War II Memory, 1984 and Beyond. Taylor & Francis. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-00-070960-5.

- Messner, Kate (2018). Sharp, Colby (ed.). The Creativity Project: An Awesometastic Story Collection. Little, Brown and Company. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-316-50778-3.

- Wendt, Simon (2018). Warring over Valor: How Race and Gender Shaped American Military Heroism in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. Rutgers University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8135-9755-3.

- Latty, Yvonne; Tarver, Ron (2012). We Were There: Voices of African American Veterans, from World War II to the War in Iraq. Amistad. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-06-226914-0.

- James Jr., Thomas S. (June 20, 2021). "77 years later, still seeking appropriate honor for a heroic Black medic on D-Day". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- "The Lion 1949" (PDF). Lincoln University. 1949. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Moreira, Gabrielle (June 4, 2019). "D-Day: Widow of African-American soldier who served in only all-black unit fights for Medal of Honor". FOX 5 New York. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- "Woodson, Waverly B". ANC Explorer. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- "The Lincoln University honors World War II hero Waverly B. Woodson and receives historical collection". Lincoln University. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Saunders, John A. (1964). 100 Years After Emancipation: History of the Philadelphia Negro, 1787 to 1963. Free African Society. p. 166.

- Converse, Elliott V.; Gibran, Daniel K.; Cash, John A. (2015). The Exclusion of Black Soldiers from the Medal of Honor in World War II: The Study Commissioned by the United States Army to Investigate Racial Bias in the Awarding of the Nation's Highest Military Decoration. McFarland & Company. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4766-0732-0.

- Beynon, Steve (September 8, 2020). "Lawmakers push for long-sought Medal of Honor for Black D-Day hero Woodson". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- "S.4535 - A bill to authorize the President to award the Medal of Honor to Waverly B. Woodson, Jr., for acts of valor during World War II". Congress.gov. 116th United States Congress (2019-2020). Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- "H.R.8194 - To authorize the President to award the Medal of Honor to Waverly B. Woodson, Jr., for acts of valor during World War II". Congress.gov. 116th United States Congress (2019-2020). Retrieved February 1, 2021.