Weakly interacting massive particle

Weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) are hypothetical particles that are one of the proposed candidates for dark matter.

There exists no formal definition of a WIMP, but broadly, it is a new elementary particle which interacts via gravity and any other force (or forces), potentially not part of the Standard Model itself, which is as weak as or weaker than the weak nuclear force, but also non-vanishing in its strength. Many WIMP candidates are expected to have been produced thermally in the early Universe, similarly to the particles of the Standard Model[1] according to Big Bang cosmology, and usually will constitute cold dark matter. Obtaining the correct abundance of dark matter today via thermal production requires a self-annihilation cross section of , which is roughly what is expected for a new particle in the 100 GeV mass range that interacts via the electroweak force.

Experimental efforts to detect WIMPs include the search for products of WIMP annihilation, including gamma rays, neutrinos and cosmic rays in nearby galaxies and galaxy clusters; direct detection experiments designed to measure the collision of WIMPs with nuclei in the laboratory, as well as attempts to directly produce WIMPs in colliders, such as the LHC.

Because supersymmetric extensions of the Standard Model of particle physics readily predict a new particle with these properties, this apparent coincidence is known as the "WIMP miracle", and a stable supersymmetric partner has long been a prime WIMP candidate.[2] However, recent null results from direct-detection experiments along with the failure to produce evidence of supersymmetry in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) experiment[3][4] has cast doubt on the simplest WIMP hypothesis.[5]

Theoretical framework and properties

WIMP-like particles are predicted by R-parity-conserving supersymmetry, a popular type of extension to the Standard Model of particle physics, although none of the large number of new particles in supersymmetry have been observed.[6] WIMP-like particles are also predicted by universal extra dimension and little Higgs theories.

| Model | parity | candidate |

|---|---|---|

| SUSY | R-parity | lightest supersymmetric particle (LSP) |

| UED | KK-parity | lightest Kaluza–Klein particle (LKP) |

| little Higgs | T-parity | lightest T-odd particle (LTP) |

The main theoretical characteristics of a WIMP are:

- Interactions only through the weak nuclear force and gravity, or possibly other interactions with cross-sections no higher than the weak scale;[7]

- Large mass compared to standard particles (WIMPs with sub-GeV masses may be considered to be light dark matter).

Because of their lack of electromagnetic interaction with normal matter, WIMPs would be invisible through normal electromagnetic observations. Because of their large mass, they would be relatively slow moving and therefore "cold".[8] Their relatively low velocities would be insufficient to overcome the mutual gravitational attraction, and as a result, WIMPs would tend to clump together.[9] WIMPs are considered one of the main candidates for cold dark matter, the others being massive compact halo objects (MACHOs) and axions. These names were deliberately chosen for contrast, with MACHOs named later than WIMPs.[10] In contrast to MACHOs, there are no known stable particles within the Standard Model of particle physics that have all the properties of WIMPs. The particles that have little interaction with normal matter, such as neutrinos, are all very light, and hence would be fast moving, or "hot".

As dark matter

A decade after the dark matter problem was established in the 1970s, WIMPs were suggested as a potential solution to the issue.[11] Although the existence of WIMPs in nature is still hypothetical, it would resolve a number of astrophysical and cosmological problems related to dark matter. There is consensus today among astronomers that most of the mass in the Universe is indeed dark. Simulations of a universe full of cold dark matter produce galaxy distributions that are roughly similar to what is observed.[12][13] By contrast, hot dark matter would smear out the large-scale structure of galaxies and thus is not considered a viable cosmological model.

WIMPs fit the model of a relic dark matter particle from the early Universe, when all particles were in a state of thermal equilibrium. For sufficiently high temperatures, such as those existing in the early Universe, the dark matter particle and its antiparticle would have been both forming from and annihilating into lighter particles. As the Universe expanded and cooled, the average thermal energy of these lighter particles decreased and eventually became insufficient to form a dark matter particle-antiparticle pair. The annihilation of the dark matter particle-antiparticle pairs, however, would have continued, and the number density of dark matter particles would have begun to decrease exponentially.[7] Eventually, however, the number density would become so low that the dark matter particle and antiparticle interaction would cease, and the number of dark matter particles would remain (roughly) constant as the Universe continued to expand.[9] Particles with a larger interaction cross section would continue to annihilate for a longer period of time, and thus would have a smaller number density when the annihilation interaction ceases. Based on the current estimated abundance of dark matter in the Universe, if the dark matter particle is such a relic particle, the interaction cross section governing the particle-antiparticle annihilation can be no larger than the cross section for the weak interaction.[7] If this model is correct, the dark matter particle would have the properties of the WIMP.

Indirect detection

Because WIMPs may only interact through gravitational and weak forces, they are extremely difficult to detect. However, there are many experiments underway to attempt to detect WIMPs both directly and indirectly. Indirect detection refers to the observation of annihilation or decay products of WIMPs far away from Earth. Indirect detection efforts typically focus on locations where WIMP dark matter is thought to accumulate the most: in the centers of galaxies and galaxy clusters, as well as in the smaller satellite galaxies of the Milky Way. These are particularly useful since they tend to contain very little baryonic matter, reducing the expected background from standard astrophysical processes. Typical indirect searches look for excess gamma rays, which are predicted both as final-state products of annihilation, or are produced as charged particles interact with ambient radiation via inverse Compton scattering. The spectrum and intensity of a gamma ray signal depends on the annihilation products, and must be computed on a model-by-model basis. Experiments that have placed bounds on WIMP annihilation, via the non-observation of an annihilation signal, include the Fermi-LAT gamma ray telescope[14] and the VERITAS ground-based gamma ray observatory.[15] Although the annihilation of WIMPs into Standard Model particles also predicts the production of high-energy neutrinos, their interaction rate is too low to reliably detect a dark matter signal at present. Future observations from the IceCube observatory in Antarctica may be able to differentiate WIMP-produced neutrinos from standard astrophysical neutrinos; however, by 2014, only 37 cosmological neutrinos had been observed,[16] making such a distinction impossible.

Another type of indirect WIMP signal could come from the Sun. Halo WIMPs may, as they pass through the Sun, interact with solar protons, helium nuclei as well as heavier elements. If a WIMP loses enough energy in such an interaction to fall below the local escape velocity, it would not have enough energy to escape the gravitational pull of the Sun and would remain gravitationally bound.[9] As more and more WIMPs thermalize inside the Sun, they begin to annihilate with each other, forming a variety of particles, including high-energy neutrinos.[17] These neutrinos may then travel to the Earth to be detected in one of the many neutrino telescopes, such as the Super-Kamiokande detector in Japan. The number of neutrino events detected per day at these detectors depends on the properties of the WIMP, as well as on the mass of the Higgs boson. Similar experiments are underway to detect neutrinos from WIMP annihilations within the Earth[18] and from within the galactic center.[19][20]

Direct detection

Direct detection refers to the observation of the effects of a WIMP-nucleus collision as the dark matter passes through a detector in an Earth laboratory. While most WIMP models indicate that a large enough number of WIMPs must be captured in large celestial bodies for indirect detection experiments to succeed, it remains possible that these models are either incorrect or only explain part of the dark matter phenomenon. Thus, even with the multiple experiments dedicated to providing indirect evidence for the existence of cold dark matter, direct detection measurements are also necessary to solidify the theory of WIMPs.

Although most WIMPs encountering the Sun or the Earth are expected to pass through without any effect, it is hoped that a large number of dark matter WIMPs crossing a sufficiently large detector will interact often enough to be seen—at least a few events per year. The general strategy of current attempts to detect WIMPs is to find very sensitive systems that can be scaled up to large volumes. This follows the lessons learned from the history of the discovery, and (by now routine) detection, of the neutrino.

Experimental techniques

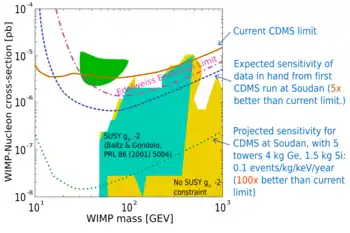

Cryogenic crystal detectors – A technique used by the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (CDMS) detector at the Soudan Mine relies on multiple very cold germanium and silicon crystals. The crystals (each about the size of a hockey puck) are cooled to about 50 mK. A layer of metal (aluminium and tungsten) at the surfaces is used to detect a WIMP passing through the crystal. This design hopes to detect vibrations in the crystal matrix generated by an atom being "kicked" by a WIMP. The tungsten transition edge sensors (TES) are held at the critical temperature so they are in the superconducting state. Large crystal vibrations will generate heat in the metal and are detectable because of a change in resistance. CRESST, CoGeNT, and EDELWEISS run similar setups.

Noble gas scintillators – Another way of detecting atoms "knocked about" by a WIMP is to use scintillating material, so that light pulses are generated by the moving atom and detected, often with PMTs. Experiments such as DEAP at SNOLAB and DarkSide at the LNGS instrument a very large target mass of liquid argon for sensitive WIMP searches. ZEPLIN, and XENON used xenon to exclude WIMPs at higher sensitivity, with the most stringent limits to date provided by the XENON1T detector, utilizing 3.5 tons of liquid xenon.[21] Even larger multi-ton liquid xenon detectors have been approved for construction from the XENON, LUX-ZEPLIN and PandaX collaborations.

Crystal scintillators – Instead of a liquid noble gas, an in principle simpler approach is the use of a scintillating crystal such as NaI(Tl). This approach is taken by DAMA/LIBRA, an experiment that observed an annular modulation of the signal consistent with WIMP detection (see § Recent limits). Several experiments are attempting to replicate those results, including ANAIS and DM-Ice, which is codeploying NaI crystals with the IceCube detector at the South Pole. KIMS is approaching the same problem using CsI(Tl) as a scintillator.

Bubble chambers – The PICASSO (Project In Canada to Search for Supersymmetric Objects) experiment is a direct dark matter search experiment that is located at SNOLAB in Canada. It uses bubble detectors with Freon as the active mass. PICASSO is predominantly sensitive to spin-dependent interactions of WIMPs with the fluorine atoms in the Freon. COUPP, a similar experiment using trifluoroiodomethane(CF3I), published limits for mass above 20 GeV in 2011.[22] The two experiments merged into PICO collaboration in 2012.

A bubble detector is a radiation sensitive device that uses small droplets of superheated liquid that are suspended in a gel matrix.[23] It uses the principle of a bubble chamber but, since only the small droplets can undergo a phase transition at a time, the detector can stay active for much longer periods. When enough energy is deposited in a droplet by ionizing radiation, the superheated droplet becomes a gas bubble. The bubble development is accompanied by an acoustic shock wave that is picked up by piezo-electric sensors. The main advantage of the bubble detector technique is that the detector is almost insensitive to background radiation. The detector sensitivity can be adjusted by changing the temperature, typically operated between 15 °C and 55 °C. There is another similar experiment using this technique in Europe called SIMPLE.

PICASSO reports results (November 2009) for spin-dependent WIMP interactions on 19F, for masses of 24 Gev new stringent limits have been obtained on the spin-dependent cross section of 13.9 pb (90% CL). The obtained limits restrict recent interpretations of the DAMA/LIBRA annual modulation effect in terms of spin dependent interactions.[24]

PICO is an expansion of the concept planned in 2015.[25]

Other types of detectors – Time projection chambers (TPCs) filled with low pressure gases are being studied for WIMP detection. The Directional Recoil Identification From Tracks (DRIFT) collaboration is attempting to utilize the predicted directionality of the WIMP signal. DRIFT uses a carbon disulfide target, that allows WIMP recoils to travel several millimetres, leaving a track of charged particles. This charged track is drifted to an MWPC readout plane that allows it to be reconstructed in three dimensions and determine the origin direction. DMTPC is a similar experiment with CF4 gas.

The DAMIC (DArk Matter In CCDs) and SENSEI (Sub Electron Noise Skipper CCD Experimental Instrument) collaborations employ the use of scientific Charge Coupled Devices (CCDs) to detect light Dark Matter. The CCDs act as both the detector target and the readout instrumentation. WIMP interactions with the bulk of the CCD can induce the creation of electron-hole pairs, which are then collected and readout by the CCDs. In order to decrease the noise and achieve detection of single electrons, the experiments make use of a type of CCD known as the Skipper CCD, which allows for averaging over repeated measurements of the same collected charge.[26][27]

Recent limits

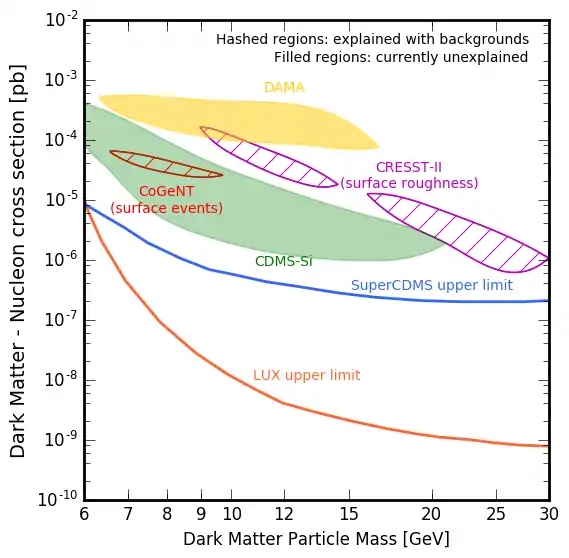

There are currently no confirmed detections of dark matter from direct detection experiments, with the strongest exclusion limits coming from the LUX and SuperCDMS experiments, as shown in figure 2. With 370 kilograms of xenon LUX is more sensitive than XENON or CDMS.[28] First results from October 2013 report that no signals were seen, appearing to refute results obtained from less sensitive instruments.[29] and this was confirmed after the final data run ended in May 2016.[30]

Historically there have been four anomalous sets of data from different direct detection experiments, two of which have now been explained with backgrounds (CoGeNT and CRESST-II), and two which remain unexplained (DAMA/LIBRA and CDMS-Si).[31][32] In February 2010, researchers at CDMS announced that they had observed two events that may have been caused by WIMP-nucleus collisions.[33][34][35]

CoGeNT, a smaller detector using a single germanium puck, designed to sense WIMPs with smaller masses, reported hundreds of detection events in 56 days.[36][37] They observed an annual modulation in the event rate that could indicate light dark matter.[38] However a dark matter origin for the CoGeNT events has been refuted by more recent analyses, in favour of an explanation in terms of a background from surface events.[39]

Annual modulation is one of the predicted signatures of a WIMP signal,[40][41] and on this basis the DAMA collaboration has claimed a positive detection. Other groups, however, have not confirmed this result. The CDMS data made public in May 2004 exclude the entire DAMA signal region given certain standard assumptions about the properties of the WIMPs and the dark matter halo, and this has been followed by many other experiments (see Fig 2, right).

The COSINE-100 collaboration (a merging of KIMS and DM-Ice groups) published their results on replicating the DAMA/LIBRA signal in December 2018 in journal Nature; their conclusion was that "this result rules out WIMP–nucleon interactions as the cause of the annual modulation observed by the DAMA collaboration".[42] In 2021 new results from COSINE-100 and ANAIS-112 both failed to replicate the DAMA/LIBRA signal[43][44][45] and in August 2022 COSINE-100 applied an analysis method similar to one used by DAMA/LIBRA and found a similar annual modulation suggesting the signal could be just a statistical artifact[46][47] supporting a hypothesis first put forward on 2020.[48]

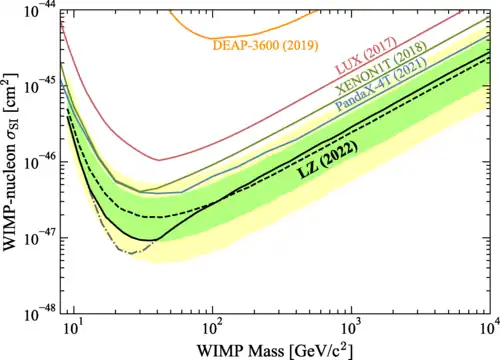

The future of direct detection

The 2020s should see the emergence of several multi-tonne mass direct detection experiments, which will probe WIMP-nucleus cross sections orders of magnitude smaller than the current state-of-the-art sensitivity. Examples of such next-generation experiments are LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) and XENONnT, which are multi-tonne liquid xenon experiments, followed by DARWIN, another proposed liquid xenon direct detection experiment of 50–100 tonnes.[49][50]

Such multi-tonne experiments will also face a new background in the form of neutrinos, which will limit their ability to probe the WIMP parameter space beyond a certain point, known as the neutrino floor. However, although its name may imply a hard limit, the neutrino floor represents the region of parameter space beyond which experimental sensitivity can only improve at best as the square root of exposure (the product of detector mass and running time).[51][52] For WIMP masses below 10 GeV the dominant source of neutrino background is from the Sun, while for higher masses the background contains contributions from atmospheric neutrinos and the diffuse supernova neutrino background.

In December 2021, results from PandaX have found no signal in their data, with a lowest excluded cross section of at 40 GeV with 90% confidence level.[53][54]

In July 2023 the XENONnT and LZ experiment published the first results of their searches for WIMPs,[55] the first excluding cross sections above at 28 GeV with 90% confidence level[56] and the second excluding cross sections above at 36 GeV with 90% confidence level.[57]

See also

- Darkon (unparticle) – Hypothetical unparticle

- Feebly interacting particle (FIP)

- Higgs boson – Elementary particle

- Massive compact halo object (MACHO) – Hypothetical form of dark matter in galactic halos

- Micro black hole – Hypothetical black holes of very small size

- Robust associations of massive baryonic objects (RAMBOs) – Proposed type of star cluster

- Weakly interacting sub-eV / slender / slight particle (WISP)

- Theoretical candidates

- Lightest supersymmetric particle (LSP) – Lightest new particle in a supersymmetric model

- Neutralino – Neutral mass eigenstate formed from superpartners of gauge and Higgs bosons

- Majorana fermion – Fermion that is its own antiparticle

- Planck-mass-sized black hole remnant – Hypothetical black holes of very small size

- Sterile neutrino – Hypothetical particle that interacts only via gravity

References

- Garrett, Katherine (2010). "Dark matter: A primer". Advances in Astronomy. 2011 (968283): 1–22. arXiv:1006.2483. Bibcode:2011AdAst2011E...8G. doi:10.1155/2011/968283.

- Jungman, Gerard; Kamionkowski, Marc; Griest, Kim (1996). "Supersymmetric dark matter". Physics Reports. 267 (5–6): 195–373. arXiv:hep-ph/9506380. Bibcode:1996PhR...267..195J. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(95)00058-5. S2CID 119067698.

- "LHC discovery maims supersymmetry again". Discovery News.

- Craig, Nathaniel (2013). "The State of Supersymmetry after Run I of the LHC". arXiv:1309.0528 [hep-ph].

- Fox, Patrick J.; Jung, Gabriel; Sorensen, Peter; Weiner, Neal (2014). "Dark matter in light of LUX". Physical Review D. 89 (10): 103526. arXiv:1401.0216. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89j3526F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.103526.

- Klapdor-Kleingrothaus, H.V. (1998). "Double beta decay and dark matter search - window to new physics now, and in future (GENIUS)". In Klapdor-Kleingrothaus, V.; Paes, H. (eds.). Beyond the Desert. Vol. 1997. IOP. p. 485. arXiv:hep-ex/9802007. Bibcode:1998hep.ex....2007K.

- Kamionkowski, Marc (1997). "WIMP and Axion Dark Matter". High Energy Physics and Cosmology. 14: 394. arXiv:hep-ph/9710467. Bibcode:1998hepc.conf..394K.

- Zacek, Viktor (2007). "Dark Matter". Fundamental Interactions: 170–206. arXiv:0707.0472. doi:10.1142/9789812776105_0007. ISBN 978-981-277-609-9. S2CID 16734425.

- Griest, Kim (1993). "The Search for the Dark Matter: WIMPs and MACHOs". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 688: 390–407. arXiv:hep-ph/9303253. Bibcode:1993NYASA.688..390G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43912.x. PMID 26469437. S2CID 8955141.

- Griest, Kim (1991). "Galactic Microlensing as a Method of Detecting Massive Compact Halo Objects". The Astrophysical Journal. 366: 412–421. Bibcode:1991ApJ...366..412G. doi:10.1086/169575.

- de Swart, J. G.; Bertone, G.; van Dongen, J. (2017). "How dark matter came to matter". Nature Astronomy. 1 (59): 0059. arXiv:1703.00013. Bibcode:2017NatAs...1E..59D. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0059. S2CID 119092226.

- Conroy, Charlie; Wechsler, Risa H.; Kravtsov, Andrey V. (2006). "Modeling Luminosity-Dependent Galaxy Clustering Through Cosmic Time". The Astrophysical Journal. 647 (1): 201–214. arXiv:astro-ph/0512234. Bibcode:2006ApJ...647..201C. doi:10.1086/503602. S2CID 13189513.

- The Millennium Simulation Project, Introduction: The Millennium Simulation The Millennium Run used more than 10 billion particles to trace the evolution of the matter distribution in a cubic region of the Universe over 2 billion light-years on a side.

- Ackermann, M.; et al. (The Fermi-LAT Collaboration) (2014). "Dark matter constraints from observations of 25 Milky Way satellite galaxies with the Fermi Large Area Telescope". Physical Review D. 89 (4): 042001. arXiv:1310.0828. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89d2001A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.042001. S2CID 46664722.

- Grube, Jeffrey; VERITAS Collaboration (2012). "VERITAS Limits on Dark Matter Annihilation from Dwarf Galaxies". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1505: 689–692. arXiv:1210.4961. Bibcode:2012AIPC.1505..689G. doi:10.1063/1.4772353. S2CID 118510709.

- Aartsen, M. G.; et al. (IceCube Collaboration) (2014). "Observation of High-Energy Astrophysical Neutrinos in Three Years of IceCube Data". Physical Review Letters. 113 (10): 101101. arXiv:1405.5303. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.113j1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.101101. PMID 25238345. S2CID 220469354.

- Ferrer, F.; Krauss, L. M.; Profumo, S. (2006). "Indirect detection of light neutralino dark matter in the next-to-minimal supersymmetric standard model". Physical Review D. 74 (11): 115007. arXiv:hep-ph/0609257. Bibcode:2006PhRvD..74k5007F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.74.115007. S2CID 119351935.

- Freese, Katherine (1986). "Can scalar neutrinos or massive Dirac neutrinos be the missing mass?". Physics Letters B. 167 (3): 295–300. Bibcode:1986PhLB..167..295F. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(86)90349-7.

- Merritt, D.; Bertone, G. (2005). "Dark Matter Dynamics and Indirect Detection". Modern Physics Letters A. 20 (14): 1021–1036. arXiv:astro-ph/0504422. Bibcode:2005MPLA...20.1021B. doi:10.1142/S0217732305017391. S2CID 119405319.

- Fornengo, Nicolao (2008). "Status and perspectives of indirect and direct dark matter searches". Advances in Space Research. 41 (12): 2010–2018. arXiv:astro-ph/0612786. Bibcode:2008AdSpR..41.2010F. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.02.067. S2CID 202740.

- Aprile, E; et al. (2017). "First Dark Matter Search Results from the XENON1T Experiment". Physical Review Letters. 119 (18): 181301. arXiv:1705.06655. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119r1301A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.181301. PMID 29219593. S2CID 45532100.

- Behnke, E.; Behnke, J.; Brice, S. J.; Broemmelsiek, D.; Collar, J. I.; Cooper, P. S.; Crisler, M.; Dahl, C. E.; Fustin, D.; Hall, J.; Hinnefeld, J. H.; Hu, M.; Levine, I.; Ramberg, E.; Shepherd, T.; Sonnenschein, A.; Szydagis, M. (10 January 2011). "Improved Limits on Spin-Dependent WIMP-Proton Interactions from a Two Liter Bubble Chamber". Physical Review Letters. 106 (2): 021303. arXiv:1008.3518. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106b1303B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.021303. PMID 21405218. S2CID 20188890.

- "Bubble Technology Industries". Archived from the original on 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- PICASSO Collaboration (2009). "Dark Matter Spin-Dependent Limits for WIMP Interactions on 19F by PICASSO". Physics Letters B. 682 (2): 185–192. arXiv:0907.0307. Bibcode:2009PhLB..682..185A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2009.11.019. S2CID 15163629.

- Cooley, J. (28 October 2014). "Overview of non-liquid noble direct detection dark matter experiments". Physics of the Dark Universe. 4: 92–97. arXiv:1410.4960. Bibcode:2014PDU.....4...92C. doi:10.1016/j.dark.2014.10.005. S2CID 118724305.

- DAMIC Collaboration; Aguilar-Arevalo, A.; Amidei, D.; Baxter, D.; Cancelo, G.; Cervantes Vergara, B. A.; Chavarria, A. E.; Darragh-Ford, E.; de Mello Neto, J. R. T.; D’Olivo, J. C.; Estrada, J. (2019-10-31). "Constraints on Light Dark Matter Particles Interacting with Electrons from DAMIC at SNOLAB". Physical Review Letters. 123 (18): 181802. arXiv:1907.12628. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.123r1802A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.181802. PMID 31763884. S2CID 198985735.

- Abramoff, Orr; Barak, Liron; Bloch, Itay M.; Chaplinsky, Luke; Crisler, Michael; Dawa; Drlica-Wagner, Alex; Essig, Rouven; Estrada, Juan; Etzion, Erez; Fernandez, Guillermo (2019-04-24). "SENSEI: Direct-Detection Constraints on Sub-GeV Dark Matter from a Shallow Underground Run Using a Prototype Skipper-CCD". Physical Review Letters. 122 (16): 161801. arXiv:1901.10478. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.122p1801A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.161801. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 31075006. S2CID 119219165.

- "New Experiment Torpedoes Lightweight Dark Matter Particles". 30 October 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- "First Results from LUX, the World's Most Sensitive Dark Matter Detector". Berkeley Lab News Center. 30 October 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Dark matter search comes up empty. July 2016

- Cartlidge, Edwin (2015). "Largest-ever dark-matter experiment poised to test popular theory". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18772. S2CID 182831370. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Davis, Jonathan H. (2015). "The Past and Future of Light Dark Matter Direct Detection". Int. J. Mod. Phys. A. 30 (15): 1530038. arXiv:1506.03924. Bibcode:2015IJMPA..3030038D. doi:10.1142/S0217751X15300380. S2CID 119269304.

- "Key to the universe found on the Iron Range?". Star Tribune. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- CDMS Collaboration. "Results from the Final Exposure of the CDMS II Experiment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2009-12-21.. See also a non-technical summary: CDMS Collaboration. "Latest Results in the Search for Dark Matter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-18.

- The CDMS II Collaboration (2010). "Dark Matter Search Results from the CDMS II Experiment". Science. 327 (5973): 1619–21. arXiv:0912.3592. Bibcode:2010Sci...327.1619C. doi:10.1126/science.1186112. PMID 20150446. S2CID 2517711.

- Eric Hand (2010-02-26). "A CoGeNT result in the hunt for dark matter". Nature. Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2010.97.

- C. E. Aalseth; et al. (CoGeNT collaboration) (2011). "Results from a Search for Light-Mass Dark Matter with a P-type Point Contact Germanium Detector". Physical Review Letters. 106 (13): 131301. arXiv:1002.4703. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106m1301A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.131301. PMID 21517370. S2CID 24822628.

- James Dacey (June 2011). "CoGeNT findings support dark-matter halo theory". physicsworld. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Davis, Jonathan H.; McCabe, Christopher; Boehm, Celine (2014). "Quantifying the evidence for Dark Matter in CoGeNT data". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 1408 (8): 014. arXiv:1405.0495. Bibcode:2014JCAP...08..014D. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2014/08/014. S2CID 54532870.

- Drukier, Andrzej K.; Freese, Katherine; Spergel, David N. (15 June 1986). "Detecting cold dark-matter candidates". Physical Review D. 33 (12): 3495–3508. Bibcode:1986PhRvD..33.3495D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.33.3495. PMID 9956575.

- K. Freese; J. Frieman; A. Gould (1988). "Signal Modulation in Cold Dark Matter Detection". Physical Review D. 37 (12): 3388–3405. Bibcode:1988PhRvD..37.3388F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.37.3388. OSTI 1448427. PMID 9958634. S2CID 2610174.

- COSINE-100 Collaboration (2018). "An experiment to search for dark-matter interactions using sodium iodide detectors". Nature. 564 (7734): 83–86. arXiv:1906.01791. Bibcode:2018Natur.564...83C. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0739-1. PMID 30518890. S2CID 54459495.

- Amaré, J.; Cebrián, S.; Cintas, D.; Coarasa, I.; García, E.; Martínez, M.; Oliván, M. A.; Ortigoza, Y.; de Solórzano, A. Ortiz; Puimedón, J.; Salinas, A. (2021-05-27). "Annual modulation results from three-year exposure of ANAIS-112". Physical Review D. 103 (10): 102005. arXiv:2103.01175. Bibcode:2021PhRvD.103j2005A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.103.102005. ISSN 2470-0010. S2CID 232092298.

- Adhikari, Govinda; de Souza, Estella B.; Carlin, Nelson; Choi, Jae Jin; Choi, Seonho; Djamal, Mitra; Ezeribe, Anthony C.; França, Luis E.; Ha, Chang Hyon; Hahn, In Sik; Jeon, Eunju (2021-11-12). "Strong constraints from COSINE-100 on the DAMA dark matter results using the same sodium iodide target". Science Advances. 7 (46): eabk2699. arXiv:2104.03537. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2699A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abk2699. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 8580298. PMID 34757778.

- "Is the end in sight for famous dark matter claim?". www.science.org. Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- Adhikari, G.; Carlin, N.; Choi, J. J.; Choi, S.; Ezeribe, A. C.; Franca, L. E.; Ha, C.; Hahn, I. S.; Hollick, S. J.; Jeon, E. J.; Jo, J. H.; Joo, H. W.; Kang, W. G.; Kauer, M.; Kim, B. H. (2023). "An induced annual modulation signature in COSINE-100 data by DAMA/LIBRA's analysis method". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 4676. arXiv:2208.05158. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.4676A. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31688-4. PMC 10033922. PMID 36949218.

- Castelvecchi, Davide (2022-08-16). "Notorious dark-matter signal could be due to analysis error". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-02222-9. PMID 35974221. S2CID 251624302.

- D. Buttazzo; et al. (2020). "Annual modulations from secular variations: relaxing DAMA?". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2020 (4): 137. arXiv:2002.00459. Bibcode:2020JHEP...04..137B. doi:10.1007/JHEP04(2020)137. S2CID 211010848.

- Malling, D. C.; et al. (2011). "After LUX: The LZ Program". arXiv:1110.0103 [astro-ph.IM].

- Baudis, Laura (2012). "DARWIN: dark matter WIMP search with noble liquids". J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 375 (1): 012028. arXiv:1201.2402. Bibcode:2012JPhCS.375a2028B. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/375/1/012028. S2CID 30885844.

- Billard, J.; Strigari, L.; Figueroa-Feliciano, E. (2014). "Implication of neutrino backgrounds on the reach of next generation dark matter direct detection experiments". Phys. Rev. D. 89 (2): 023524. arXiv:1307.5458. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89b3524B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.023524. S2CID 16208132.

- Davis, Jonathan H. (2015). "Dark Matter vs. Neutrinos: The effect of astrophysical uncertainties and timing information on the neutrino floor". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 1503 (3): 012. arXiv:1412.1475. Bibcode:2015JCAP...03..012D. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2015/03/012. S2CID 118596203.

- Meng, Yue; Wang, Zhou; Tao, Yi; Abdukerim, Abdusalam; Bo, Zihao; Chen, Wei; Chen, Xun; Chen, Yunhua; Cheng, Chen; Cheng, Yunshan; Cui, Xiangyi (2021-12-23). "Dark Matter Search Results from the PandaX-4T Commissioning Run". Physical Review Letters. 127 (26): 261802. arXiv:2107.13438. Bibcode:2021PhRvL.127z1802M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.261802. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 35029500. S2CID 236469421.

- Stephens, Marric (2021-12-23). "Tightening the Net on Two Kinds of Dark Matter". Physics. 14. Bibcode:2021PhyOJ..14.s164S. doi:10.1103/Physics.14.s164. S2CID 247277808.

- Day, Charles (2023-07-28). "The Search for WIMPs Continues". Physics. 16: s106. Bibcode:2023PhyOJ..16.s106D. doi:10.1103/Physics.16.s106. S2CID 260751963.

- XENON Collaboration; Aprile, E.; Abe, K.; Agostini, F.; Ahmed Maouloud, S.; Althueser, L.; Andrieu, B.; Angelino, E.; Angevaare, J. R.; Antochi, V. C.; Antón Martin, D.; Arneodo, F.; Baudis, L.; Baxter, A. L.; Bazyk, M. (2023-07-28). "First Dark Matter Search with Nuclear Recoils from the XENONnT Experiment". Physical Review Letters. 131 (4): 041003. arXiv:2303.14729. Bibcode:2023PhRvL.131d1003A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.041003. PMID 37566859. S2CID 257767449.

- LUX-ZEPLIN Collaboration; Aalbers, J.; Akerib, D. S.; Akerlof, C. W.; Al Musalhi, A. K.; Alder, F.; Alqahtani, A.; Alsum, S. K.; Amarasinghe, C. S.; Ames, A.; Anderson, T. J.; Angelides, N.; Araújo, H. M.; Armstrong, J. E.; Arthurs, M. (2023-07-28). "First Dark Matter Search Results from the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) Experiment". Physical Review Letters. 131 (4): 041002. arXiv:2207.03764. Bibcode:2023PhRvL.131d1002A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.041002. PMID 37566836. S2CID 250343331.

Further reading

- Bertone, Gianfranco (2010). Particle Dark Matter: Observations, Models and Searches. Cambridge University Press. p. 762. Bibcode:2010pdmo.book.....B. ISBN 978-0-521-76368-4.

- Cerdeño, David G.; Green, Anne M. (2010). Bertone, Gianfranco (ed.). "Direct detection of WIMPs". Particle Dark Matter: Observations, Models and Searches: 347–369. arXiv:1002.1912. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511770739.018. ISBN 9780511770739. S2CID 119311963.

- Davis, Jonathan H. (2015). "The Past and Future of Light Dark Matter Direct Detection". Int. J. Mod. Phys. A. 30 (15): 1530038. arXiv:1506.03924. Bibcode:2015IJMPA..3030038D. doi:10.1142/S0217751X15300380. S2CID 119269304.

- Del Nobile, Eugenio; Gelmini, Graciela B.; Gondolo, Paolo; Huh, Ji-Haeng (2015). "Update on the Halo-independent Comparison of Direct Dark Matter Detection Data". Physics Procedia. 61: 45–54. arXiv:1405.5582. Bibcode:2015PhPro..61...45D. doi:10.1016/j.phpro.2014.12.009.

External links

- Particle Data Group review article on WIMP search (S. Eidelman et al. (Particle Data Group), Phys. Lett. B 592, 1 (2004) Appendix : OMITTED FROM SUMMARY TABLE)

- Timothy J. Sumner, Experimental Searches for Dark Matter in Living Reviews in Relativity, Vol 5, 2002

- Portraits of darkness, New Scientist, August 31, 2013. Preview only.

- Hooper, Dan (13 April 2018). The WIMP is dead. Long live the WIMP! (video; colloquium). Brown University Department of Physics. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11.