The Kin-der-Kids

The Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie's World were early newspaper comics by painter Lyonel Feininger and published by the Chicago Sunday Tribune during 1906–07.

Similar in form to Little Nemo and the later Sunday editions of Krazy Kat, most of Feininger's comics occupied a full-page and were rendered in color. The Kin-der-Kids were published in Tribune papers beginning April 29, 1906. Feininger's second feature, Wee Willie Winkie's World, was published concurrently with The Kin-der-Kids from August 19, 1906, until The Kin-der-Kids's cancellation on November 18, 1906. Wee Willie Winkie's World ended three months later, on February 17, 1907. The series' short existences have been attributed to several causes, including Feininger being unable to produce two strips of finely detailed artwork on a weekly schedule, and personal conflict between Feininger and his publishers.[1]

Much like The New York Herald's Little Nemo, Tribune publishers envisioned The Kin-der-kids as a relatively sophisticated alternative to the comical, and at times violent, antics of Happy Hooligan and The Katzenjammer Kids, comic strips published in newspapers owned by Hearst and Pulitzer.[2]

Characters and story

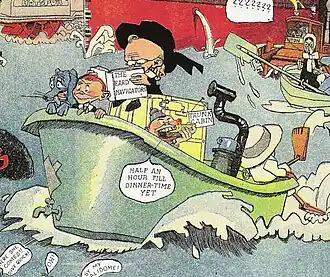

The Kin-der-Kids featured an ongoing story about the three Kin-der brothers who, along with their dog and a mechanical boy, sailed in the family's antique bathtub to explore the world. The story implies that the Kin-ders sailed for a specific reason: early on they receive a note – unseen to the reader – from Mysterious Pete which contains instructions for their journey. These instructions and the purpose of their journey remain indeterminate for the life of the comic.

The primary cast of The Kin-der-Kids were introduced to Tribune readers before the commencement of the comic strip's regular publication. On April 29, 1906, the Tribune published a special "All About the Tribune's New Comic Supplement" section. The cover featured a caricature of "Uncle" Feininger suspending the cast marionette-like on strings. The "New Comic Supplement" introduction also included a page of color portraits of the characters, and inside the supplement were prose biographies of the characters.

The cast introduced in this publication are:

- Daniel Webster: The bookish leader of the children, he is frequently preoccupied with his reading, appealing to them with "oh, don't disturb me," when the other children alert him to happenings around them. Daniel's design is notably similar to that of Wee Willie Winkie.

- Pie-Mouth: The second of the children, a boy with an enormous mouth and an equally enormous appetite.

- Strenuous Teddy: The most physical of the Kin-der kids, frequently demonstrating feats of strength.

- Little Japansky: A clockwork boy-like machine found in the sea by Uncle Kin-der. Described as a "water baby," Japansky is mechanical device lost by a Japanese submarine, not a living child.

- Sherlock Bones: Daniel Webster's dog, a blue dachshund who accompanies the children on their adventures.

- Aunt Jim-Jam and Gussie: Portrayed as over-worrying and concerned for the Kin-ders' safety, Aunt Jim-Jam pursues the Kids in a hot-air balloon to ensure that they receive their doses of castor oil. She is accompanied by her son, Gussie, and their pet cat. Along the way they pick up another traveler, Mr. Buggins, who was not mentioned in the April 29th introduction.

- Mysterious Pete and his hound: Mysterious Pete is a strange visitor wrapped in a large blue cloak and a big hat, with one eye peering out. Pete floats on a cloud, accompanied by his dog, to deliver messages to the rest of the cast, and occasionally to rescue them from trouble. He is described by other characters as some kind of ghost, prefers buckskin clothing, and has a western style revolver at the ready. Although he initially gives the children their instructions, it is also he who sets Aunt JimJam and company in pursuit of the children.

- The Pillsbury Family: Mister Phileas P. Pillsbury, possibly a snake oil salesman, is the inventor of "The Pillsbury Universal Growing Pill," which he seeks to travel the world marketing, along with five young daughters. The Pillsburys are introduced as major characters, however they only make one minor appearance in the course of the strip's life.

- Uncle Kin-der: the Kids' good-natured uncle and "nominal" head of the Kin-der family. Uncle Kin-der is never seen again after the strip's introduction.

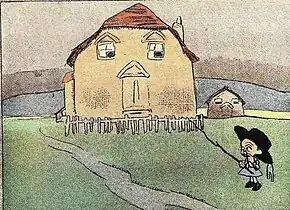

Wee Willie Winkie's World

Unlike The Kin-der-Kids, Wee Willie Winkie's World was not a continuing adventure. Each comic strip features the eponymous protagonist observing the surreal countryside around his grandfather's home. He interacts with the inanimate objects around him which have anthropomorphic qualities. Instead of speech balloon spaces, the comic strip uses captions that accompany the images.

After publication

When Wee Willie Winkie's World ceased publication in 1907, it proved to be the last comic strip Feininger would create, although he would later use similar designs for his wooden landscape sculptures (photographs of which were released in a 1965 book City at the Edge of the World.) Despite the strips' short lives, they are praised by later comics enthusiasts. The Kin-der-Kids's "full-fledged, frankly suspenseful week-to-week continuity", writes cartooning historian Bill Blackbeard, was a "real innovation for the time" when even Winsor McCay's Little Nemo had not yet developed into ongoing stories.[3] The artwork is lauded as well, and has been called "exquisitely drawn" in Time.[4]

Art Spiegelman, editor of Raw and author of Maus, praises the Kin-der-Kids as Feininger's crowning achievement:

Feininger's visually poetic formal concerns collided comically with the fishwrap disposability of news print ... The cartoonist, a New Yorker who had emigrated to Germany at sixteen and returned to safe harbor in America in 1937 became a celebrated second-generation cubist, one of the Bauhaus boys, but his handful of Sunday pages – testing the uncharted waters between the high and low arts, between European and American graphic traditions – remains his greatest aesthetic triumph."[5]

In 1994, the entirety of Feininger's comics were collected in a single volume by Kitchen Sink Press: The Comic Strip Art of Lionel Feininger. In 1999, The Comics Journal included The Kin-der-Kids in its "Top 100 Comics list".

In 2011 Sunday Press Books published the book: Forgotten Fantasy: Sunday Comics 1900-1915, ISBN 978-0-97688-859-8, collecting the complete The Kin-der-Kids and the complete Wee Willie Winkie's World.

References

- Lyonel Feininger at Con Markstein's 'Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015.

- Blackbeard, Bill "Wee Willie Winkie, Tall Uncle Feininger, and the Comic Strip Horrors of 1906: How Auntie Jim-Jam was No Antidote but Genius Triumphed". The Comic Strip Art of Lionel Feininger Kitchen Sink Press, Northampton, MA: 1994. p. 3–4.

- Blackbeard, 4.

- Time (1965-04-09). "Good Grief". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

... and the long-gone Kinder Kids, a strip exquisitely drawn by the cubist artist Lyonel Feininger.

- Spiegelman, Art. "The Comics Supplement". In the Shadow of No Towers. New York: Pantheon Books, 2004.