Gogra, Ladakh

Gogra[lower-alpha 1] (also referred to as Nala Junction)[4] is a pasture and campsite in the Ladakh union territory of India, near its disputed border with China. It is located in the Kugrang River[lower-alpha 2] valley, a branch valley of Chang Chenmo Valley, where the Changlung River flows into Kugrang. During the times of the British Raj, Gogra was a halting spot for travellers to Central Asia via the 'Chang Chenmo route', who proceeded through the Changlung river valley and the Aksai Chin plateau.[7]

Gogra | |

|---|---|

Camping ground and border outpost | |

Gogra | |

| Coordinates: 34°21′36″N 78°52′26″E | |

| Country | |

| Union territory | Ladakh |

| District | Leh |

| Elevation | 4,750 m (15,570 ft) |

| Gogra, Ladakh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 戈格拉 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 戈格拉 | ||||||

| |||||||

In the late 1950s, China began to claim the Changlung river valley as its own territory. Clashes occurred here during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. During the 2020–2022 skirmishes, the area around Gogra was again a scene of conflict, and continues to be a subject of active dispute between the two countries.[8]

Geography

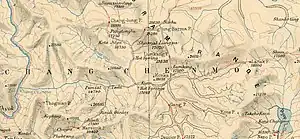

The Chang Chenmo ("Great Northern") Valley lies in a depression between the Karakoram Range in the north and the Chang Chenmo Range in the south.[9][lower-alpha 3] The Changchenmo river flows through the depression, originating near Lanak La and joining the Shyok River in the west.

Immediately to the north of Chang Chenmo, the Karakoram range divides into multiple branches, between which lie the Kugrang Valley and Changlung Valley, both running northwest–southeast.[11] The Kugrang river flows southeast within territory under present Indian control, joining the Chang Chenmo River near Hot Springs (also called Kyam or Kayam). The Changlung river flows in territory under present Chinese control, but bends southwest a little above this junction and flows into the Kugrang River near the pasture of Gogra.[12][13][14] The combined river of Kugrang and Changlung is much more voluminous than the Changchenmo stream flowing from Lanak La, so much so that Hedin regarded Changchenmo as a tributary of Kugrang.[5]

Gogra thus forms a key link, connecting the Kugrang valley, Changlung valley and Chang Chenmo. It was also called "Nala Junction" or "Nullah Junction" (junction of rivers) by the Indian military in the 1950s and 1960s.[15]

The Chang Chenmo river as well as its tributaries flow on gravel beds which are essentially barren. The valleys are dotted with occasional alluvial patches where vegetation is found. Hot Springs and Gogra are two such patches. They were historical halting places for travellers and trading caravans, with a supply of water, fuel and fodder. Nomadic Ladakhi graziers also used them for grazing cattle.[12]

Eight miles to the north of Gogra along the Changlung valley is a second hot spring, currently known by its Chinese name Wenquan (Chinese: 温泉; pinyin: Wēnquán). Here, a one-foot tall jet of hot water at 150 °F is said to emanate from a rounded boulder. Several other warm springs are also present in the vicinity.[16] China established a military post at this location in 1962.[17]

About two miles west of Wenquan, Changlung is joined by a tributary called Shamal Lungpa[lower-alpha 4] from the northeast. It provided a popular route to the Lingzithang plains via the Changlung Burma pass. About a mile upstream from the mouth of the stream is a camping ground of the same name, which was regarded as the next stage from Gogra for travellers.[21][22]

History

The first European to traverse Gogra was Adolf Schlagintweit in 1857, accompanied by his Yarkandi guide Mohammed Amin. It is said that his men had to dig steps in the Changlung valley for the ponies to ascend the slope. Schlagintweit went on to Nischu and the Aksai Chin plateau via this route. Then he proceeded to Yarkand, where he was killed in an insurrection.[3]

Amin later entered the service of the Punjab department of trade in British India.[23] With his information, the British were inspired to develop a trade route between Punjab and Yarkand via this route, which came to be called the "Chang Chenmo route". They signed a treaty with the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, who was persuaded to "develop" the route.[24] A sarai (rest house) with facilities was built at Gogra and was stocked with grains and supplies for travellers.[1][12][25] The route was in use between 1870–1884, but did not prove to be popular with the traders. It was abandoned in 1884.[24]

The Kugrang valley and Gogra also formed a popular hunting spot for British officers on leave.[14][26]

Sino-Indian border dispute

.jpg.webp)

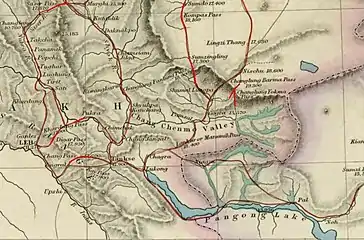

After India became independent in 1947 and China took control of Tibet in 1950, both the countries laid claim to the Aksai Chin plateau. In its 1956 border definition, China claimed the Chang Chenmo Valley up to the Kongka Pass, near Kayam Hot Springs, but excluded the majority of the eastern Karakoram range. In particular, the Changlung valley, Shamal Lungpa campsite and the Wenquan hot spring were all left as Indian territory. (Map 4)

Not recognising Chinese claims, India continued to send border patrols in "all directions". In 1957, one party went via Gogra and Shamal Lungpa to Dehra Compass, Sumdo and Karatagh Pass.[18] Finding telltale signs of Chinese activity, the border police decided to strengthen outposts by stocking them with essentials at Kayam Hot Springs and Shamal Lungpa.[27] In 1958, the border police again used this route to go to the Sarigh Jilganang lake and to the Ladakh border, planting an Indian flag at the latter location.[28] In 1959, a police party sent to set up police posts at Tsogtsalu, Hot Springs and Shamal Lungpa was confronted by Chinese troops when it tried to reconnoitre in the Chinese claimed area, and a serious clash occurred. The ensuing Kongka Pass incident exacerbated tensions between the two countries.

After the Kongka Pass incident, the two countries engaged in serious negotiations. A summit between the prime ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Zhou En-lai was held in 1960, where Zhou is believed to have proposed an "east west swap" of disputed territories. India is believed to have rejected such a barter.[29] Sector-by-sector border discussions were held later in 1960 between the officials of the two countries, where China enlarged its border claims.[30] (See Map 4.) In the vicinity of the Kugrang valley, the Chinese officials declared:

Thence [the traditional customary line] passes through peak 6,556 (approximately 78° 26' E, 34° 32' N), and runs along the watershed between the Kugrang Tsangpo River and its tributary the Changlung River to approximately 78° 53' E, 34° 22' N. where it crosses the Changlung River. It then follows the mountain ridge in a south-easterly direction up to Kongka Pass.[31]

The new "1960 claim line" meant that China laid claim to the entire basin of the Changlung river, stopping just before its confluence with the Kugrang river. Even then, the "approximately" described coordinates, 34°22′N 78°53′E, are problematic in that they lie within the Kugrang river valley, dropping below the watershed. The place where the "watershed between the Kugrang Tsangpo River and Changlung River" crosses the Changlung River is determined by Indians to be 34°23′N 78°53.5′E, where a post called "Nala Jn" was established by them.[32]

1962 standoff

In the summer of 1962, sensing that China was trying to advance to its 1960 claim line, India initiated what came to be called the "forward policy", setting up advance posts in the territory between the 1960 and 1956 claim lines. The 1/8 Gorkha Riles battalion was ordered to set up a post in the upper reaches of the Galwan River. Setting out from Phobrang, the platoon first established a base at Kayam Hot Springs. A platoon of the 'A' Company then moved towards Galwan in July 1962. Along the way it set up a post near Gogra called "Nala Jn".[32] China gave the coordinates of the post as 34°23′N 78°53.5′E,[33] which lie along the ridge dividing Kugrang and Changlung. The date of establishment of the post was 2 July 1962.[15]

By this time, the Chinese troops already had a post at Shamal Lungpa. (Map 4, blue line) So the Nala Jn post would appear to be a defensive post meant to secure the Kugrang valley. The Gorkha Rifles used an alternative route through the Kugrang valley to Galwan, setting up a post in its vicinity on 5 July.[lower-alpha 5] Despite a seriously threatening posture by the Chinese troops, the post held firm and remained intact until the beginning of the war in October 1962. It was supplied by air. Despite a supply route having been established through the Kugrang Valley, it was seen that its use would be provocative.[36][37] Indian sources claim that additional supporting posts were set up by the Indian troops: a "ration party" post at 34°34.5′N 78°38.5′E and observation posts at 34°34.5′N 78°35.5′E and 34°39.5′N 78°44′E.[38]

1962 war

The Sino-Indian War began in the western sector on 19 October 1962. The Chinese attacked all Indian posts that were beyond their 1960 claim line. The Nala Jn post, which was technically beyond the line, was also fired upon. The section of troops manning the post sustained some casualties. Their telephone line was also cut. So the commander sent two men to the Hot Springs base to report the firing, and a reinforcement of a section of troops arrived on 25 October. However, the Chinese did not attack the post, and it remained intact till the end of the war.[39]

The Line of Actual Control resulting from the war remained on the dividing ridge between the Kugrang and Changlung valleys.

2020–2022 standoff

In April 2020, Chinese forces amassed on the border of Ladakh and started intruding into previously uncontrolled territory at several points. Gogra was one of them.[41] Indian forces had their base at the Karam Singh Post (34.2980°N 78.8949°E) near Hot Springs, and periodically patrolled up to the location of the erstwhile "Nala Jn" post on the Line of Actual Control, now called Patrol Point 17A (PP-17A).[42] Around 5 May, clusters of Chinese forces appeared in its vicinity and soon blocked the Indian forces from patrolling up to this point.[43] The Indian Army moved troops to the border in a counter deployment effort, which was completed by early June.[44]

On 6 June 2020, the senior military commanders of the sides met at the Chushul–Moldo Border Personnel Meeting point, and agreed to a "disengagement" of forward troops, to be followed by an eventual "de-escalation". However, this was not followed through. Inexplicably, there was no pull-back at Gogra and Hot Springs. At the Galwan valley, the Chinese forces continued to remain at the disputed border point, leading to a clash between the two sides on 15 June.[44]

Following the clash, the Chinese forces doubled down at all the friction points. Near Gogra, the Chinese forces came down 2–4 km from the Line of Actual Control, and set up posts close to Gogra itself. According to Lt. Gen. H. S. Panag, "the Chinese intrusion here [near Gogra] denies India access to nearly 30-35 km long and 4-km wide Kugrang river valley beyond Gogra.".[45] It took several months and 10 rounds of talks between the military commanders to agree on the first pull-back in February 2021, viz., at Fingers 4–8 on the bank of the Pangong Lake.[46] In the 12th round of talks in August 2021, the two sides agreed to disengage at Gogra. It was reported that troops of both the sides dismantled all temporary structures and allied infrastructure and moved back from forward positions.[47]

However, a de-escalation has not yet taken place. Both the sides continue to claim the area in dispute, and continue to deploy troops in strength behind the forward lines. India has demanded the status quo ante April 2020 to be restored, while China is believed to insist upon imposing the "1959 claim line", either by physical denial or via a "buffer zone".[48][lower-alpha 7]

See also

Notes

- Alternative spellings: Gokra[2] and Goghra.[3]

- Alternative spellings: Khugrang, Kograng,[5] and Kugrung.[6]

- The depression is now recognized as a geological fault called the Longmu Co fault, part of the larger Longmu–Gozha Co fault system.[10]

- Alternative spellings: Shamul Lungpa,[18] Shammul Lungpa[19] and Shummal Lungpa.[20]

- China provided the coordinates of the post as "34 degrees 37 minutes 30 seconds north, 78 degrees 35 minutes 30 seconds east" (34°37.5′N 78°35.5′E) and described it as "six kilometres inside Chinese territory in the Galwan Valley area".[34] The alternative route used by Gorkha Rifles was most likely through the "Jianan Pass" in the Chinese nomenclature, which gives rise to a tributary of Kugrang in the south, and a tributary of Galwan called Shimengou (Chinese: 石门沟; pinyin: Shímén gōu) in the north. The coordinates provided by China are in the valley of Shimengou. India does not have a name for the Jianan Pass and refers to it as Patrol Point 15 (PP-15).[35]

- Borders shown are those marked by OpenStreetMap and may not be accurate.

- A "buffer zone", a concept introduced in the Galwan Valley de-escalation, means that both the sides do not occupy or patrol a defined area. Indian commentators have stated that these "buffer zones" were entirely on the Indian side of the Line of Actual Control and, so, amounted to a cession of territory.

References

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 334.

- Geological Survey of India (1883). Lydekker: The Geology of Kashmir and Chamba Territories and the British District of Khagan. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India. Vol. XXII.

- Hedin, Sven (1922), Southern Tibet, Vol. VII – History of Exploration in the Kara-korum Mountains, Stockholm: Lithographic Institute of the General Staff of the Swedish Army, p. 224 – via archive.org

- Sandhu, Shankar & Dwivedi, 1962 from the Other Side of the Hill (2015), pp. 53–54.

- Hedin, Southern Tibet, Vol. IV (1922), pp. 11–12

- Kapadia, Harish (2005), Into the Untravelled Himalaya: Travels, Treks, and Climbs, Indus Publishing, p. 215, ISBN 978-81-7387-181-8

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), pp. 256, 334.

- Sudha Ramachandran (8 August 2021), "Indian and Chinese Troops Disengage from Gogra", The Diplomat

- Trinkler, Emil (1931), "Notes on the Westernmost Plateaux of Tibet", The Himalayan Journal, 3

- Chevalier, Marie-Luce; Pan, Jiawei; Li, Haibing; Sun, Zhiming; Liu, Dongliang; Pei, Junling; Xu, Wei; Wu, Chan (2017). "First tectonic-geomorphology study along the Longmu–Gozha Co fault system, Western Tibet". Gondwana Research. 41: 411–424. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2015.03.008. ISSN 1342-937X.

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 106.

- Drew, Frederic (1875). The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories: A Geographical Account. E. Stanford. pp. 329–330 – via archive.org.

-

Ward, A.E. (1896). The Tourist's And--sportsman's Guide to Kashmir and Ladak, &c. Thacker, Spink. p. 106.

The Changlung stream joins the Kugrang near Gogra

-

Hayward, G. W. (1870). "Journey from Leh to Yarkand and Kashgar, and Exploration of the Sources of the Yarkand River". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 40: 33–37. doi:10.2307/1798640. ISSN 0266-6235. JSTOR 1798640.

(p. 33) 'Kiam' and 'Gogra' located near bottom of last map insert ... (p. 37) Chang Chenmo is now well known, being visited every year by at least half-a-dozen officers on long leave to Kashmir. The game to be found...

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 104.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 327.

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 55: "Having completed the Sumdo-Lingzithang road the Chinese troops established a post at 79°08'00"E, 34°33'00"N in the south of Nischu and named it Road JN. From this point they advanced southward and established another post at 78°35'00"E, 34°25'00"N [sic] near HS(C) in the Changlung valley: it was named HS(C)." ["HS(C)" stands for "Hot Spring (China)"]

- Mullik, The Chinese Betrayal (1971), p. 200.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 257.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 745.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), pp. 745, 975.

- Mason, Kenneth (1929), Routes in the Western Himalaya, Kashmir Etc., Vol. I, Calcutta: Government of India Press, pp. 198-200 – via archive.org,

Route 92. Tankse to Shahidulla, via Lingzi-Thang plains—329 miles

- Brescius, Moritz von (2019), German Science in the Age of Empire, Cambridge University Press, pp. 196–197, ISBN 978-1-108-42732-6

- Rizvi, Janet (1999), Trans-Himalayan Caravans: Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh, Oxford University Press, pp. 30–31, ISBN 978-0-19-564855-3

- Accounts and Papers. East India. Vol. XLIX. House of Commons, British Parliament. 1874. pp. 23–33.

(p. 23) From Gogra there are two routes to Shadula in Yarkand (p. 33) Every endeavour has been made to improve the Changchenmo route--serais having been built at some places, and depots of grain established as far as Gogra

- H.I.N. (1902). "Sport in the Changchenmo Valley, Ladakh". The Navy and Army Illustrated. Vol. 15. London: Hudson & Kearns. p. iv.

- Mullik, The Chinese Betrayal (1971), pp. 200–201.

- Mullik, The Chinese Betrayal (1971), pp. 201–202.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 86: "The prime minister had already made up his mind not to trade territory with the Chinese."

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 92: "[The Chinese map] indicated that the Chinese had substantially enlarged their claims to territory in the Western Sector."

- Report of the Officials (1962), p. CR-1.

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 104: "On July 2 Captain G Kotwal (of 1/8th G. R.), 1 JCO and 31 ORs reached the nullah junction ([34°20'50" N, 78°53'30" E]) and the next day at [34°23'00"N, 78°53'30"E] and established a post at the latter (named Nullah Jn)."

- India, White Paper VII (1962), pp. 81–82: (Note given by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Peking to the Embassy of India in China, 10 September 1962) "The fourth [strongpoint] is located at approximately 34° 23' N, 78° 53.5' E, which is northwest of the Kongka Pass and inside Sinkiang."

- United States. Central Intelligence Agency (1962), Daily Report, Foreign Radio Broadcasts, p. BBB1

- H. S. Panag, India, China’s stand on Hot Springs has 2 sticking points — Chang Chenmo, 1959 Claim Line, The Print, 14 April 2022.

- Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), pp. 102–104.

- Maxwell, India's China War (1970), pp. 238–239.

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 102.

- Johri, Chinese Invasion of Ladakh (1969), p. 118.

- Report of the Officials (1962), p. CR-1: Thence [the traditional customary boundary] passes through peak 6,556 (approximately 78° 26' E, 34° 32' N), and runs along the watershed between the Kugrang Tsangpo River and its tributary the Changlung River to approximately 78° 53' E, 34° 22' N. where it crosses the Changlung River.

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p. 4: "Towards mid-April the PLA, using these forces, occupied a number of areas claimed by both sides. The Chinese moved at five points simultaneously—Galwan river valley, the northern bank of the Pangong Tso lake, Hot Springs/Gogra, Depsang plains and the Charding Nala area of Demchok—and blocked Indian efforts to patrol up to what they understood to be the border.".

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p. 11, Figure 2.

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p. 4.

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p. 7.

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p. 10.

- Joshi, Eastern Ladakh (2021), p. 8.

- India, China disengage from Gogra Post in eastern Ladakh after 12th round of talks, The Indian Express, 6 August 2021.

- H. S. Panag, India-China talks on Ladakh face-off have hit a wall. Only a Modi-Xi summit can resolve it, The Print, 12 May 2022.

Bibliography

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: July 1962 - October 1962, White Paper No. VII (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs

- India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press

- Palat, Madhavan K., ed. (2016) [1962], "Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question", Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series, Volume 66, Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund/Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-01-994670-1-3 – via archive.org

- Johri, Sitaram (1969), Chinese Invasion of Ladakh, Himalaya Publications

- Joshi, Manoj (2021), Eastern Ladakh, the Longer Perspective, Observer Research Foundation

- Hedin, Sven (1922), Southern Tibet, Vol. IV – Kara-korum and Chang-Tang, Stockholm: Lithographic Institute of the General Staff of the Swedish Army

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1 – via archive.org

- Mullik, B. N. (1971), My Years with Nehru: The Chinese Betrayal, Allied Publishers – via archive.org

- Sandhu, P. J. S.; Shankar, Vinay; Dwivedi, G. G. (2015), 1962: A View from the Other Side of the Hill, Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-93-84464-37-0