Vestmannaeyjar

Vestmannaeyjar (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈvɛstˌmanːaˌeiːjar̥], sometimes anglicized as Westman Islands) is a municipality and archipelago off the south coast of Iceland.[1]

Vestmannaeyjar | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

View of Vestmannaeyjabær | |

Location of the Municipality of Vestmannaeyjar | |

Vestmannaeyjar Location of Vestmannaeyjar in Iceland | |

| Coordinates: 63°25′00″N 20°17′00″W | |

| Country | Iceland |

| Constituency | South Constituency |

| Region | Southern Region |

| County | Vestmannaeyjar[nb 1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Íris Róbertsdóttir (2022–present) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17 km2 (7 sq mi) |

| Population (2014) | |

| • Total | 4,264 |

| • Density | 250.82/km2 (649.6/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| Post code | IS-900, 902 |

| Website | www |

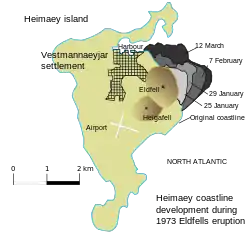

The largest island, Heimaey, has a population of 4,414,[2] most of whom live in the archipelago's main town, Vestmannaeyjabær. The other islands are uninhabited, although six have single hunting cabins. Vestmannaeyjar came to international attention in 1973 with the eruption of Eldfell volcano, which destroyed many buildings and forced a month-long evacuation of the entire population to mainland Iceland. Approximately one-fifth of the town was destroyed before the lava flow was halted by application of 6.8 billion litres of cold sea water.[3]

Geography

The Vestmannaeyjar archipelago is young in geological terms. The islands lie in the Southern Icelandic Volcanic Zone and have been formed by eruptions over the past 10,000–12,000 years. The volcanic system consists of 70–80 volcanoes both above and below the sea.[4]

Vestmannaeyjar comprises the following islands:

- Heimaey (13.4 square kilometres; 5.2 sq mi)

- Surtsey (1.4 square kilometres; 0.54 sq mi)

- Elliðaey (0.45 square kilometres; 0.17 sq mi)

- Bjarnarey (0.32 square kilometres; 0.12 sq mi)

- Álsey (0.25 square kilometres; 0.097 sq mi)

- Suðurey (0.20 square kilometres; 0.077 sq mi)

- Brandur (0.1 square kilometres; 0.039 sq mi)

- Hellisey (0.1 square kilometres; 0.039 sq mi)

- Súlnasker (0.03 square kilometres; 7 acres)

- Geldungur (0.02 square kilometres; 5 acres)

- Geirfuglasker (0.02 square kilometres; 5 acres)

- the islands Hani Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈhaːnɪ], Hæna Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈhaiːna], Hrauney Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈr̥œːinˌeiː] and the skerry Grasleysa Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈkrasˌleiːsa] are called Smáeyjar (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈsmauːˌeiːjar̥], small islands).

Total: 16.3 square kilometres (6.3 sq mi)

There are 18 islands and about 30 rock stacks and skerries. All the islands have been built up in submarine eruptions and consist of alternating layers of palagonite tuff and lava. The oldest geological formations are in the northern part of Heimaey ("Home Island"), the largest island and the only inhabited one. Basalt columns can be seen in many places, and the sea has eroded the soft rock of the shoreline and scooped out many picturesque coves and grottos, which are among the special features of the islands.

There was a submarine eruption southeast of Hellisey in 1896. The next eruption began on 14 November 1963. It lasted about four years – one of the longest in Icelandic history – and gave birth to Surtsey, the 15th island in the group. In the eruption of 1973 that lasted for 155 days, Heimaey grew by about 2.1 square kilometres (0.81 sq mi). The Vestmannaeyjar group is about 38 kilometres (24 mi) long and 29 kilometres (18 mi) broad, the closest point lying about 8 kilometres (5 mi) from the mainland.

Biodiversity

There is generally very little snow, but a lot of rain. Owing to this microclimate, returning migrant birds are often first seen in the spring and they set out from the islands in the autumn. All of Iceland's seabirds can be found in Vestmannaeyjar: the guillemot, gannet, kittiwake, Iceland gull, and puffin. The puffin is the most plentiful species and is the Vestmannaeyjar emblem. More than 30 species of birds nest in their millions in the cliffs and grassy ledges, and other species make irregular appearances.

There are about 150 plant species in the flora of the islands, and about 80 types of insect have been identified. The waters around the Vestmannaeyjar contain some of the North Atlantic's richest fishing grounds. The two main commercially exploited species in Iceland, cod and haddock, are found in abundance in Vestmannaeyjar. Other species, such as flat-fish, herring and capelin, are also commonly harvested as they migrate through the area in the autumn and winter. Lobsters and ocean perch are found in large numbers in the deep water to the southeast of the islands. Seals, small types of whale and other marine species are also present in large numbers around the islands.

The townspeople have a tradition of guiding stray puffins to safe locations.[5]

Climate

With extremely high precipitation considering the latitude, Vestmannaeyjar features a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc) under the Köppen climate classification. It is often very windy in the islands, and the highest wind speed measured in Iceland (61 metres per second; 140 mph; 220 km/h) was recorded in Stórhöfði, the southern of the island's two major peninsulae. The main wind directions are easterly and south-easterly. The islands enjoy the country's highest average annual temperature, the Gulf Stream having a strong warming effect, especially in winter.

| Climate data for Vestmannaeyjar (1981-2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.7 (3.7) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 152.2 (5.99) |

142.0 (5.59) |

130.8 (5.15) |

110.7 (4.36) |

96.8 (3.81) |

82.6 (3.25) |

109.4 (4.31) |

144.2 (5.68) |

135.0 (5.31) |

141.9 (5.59) |

149.4 (5.88) |

153.6 (6.05) |

1,548.6 (60.97) |

| Average precipitation days | 18.8 | 18.1 | 17.3 | 15.3 | 13.7 | 11.1 | 13.7 | 15.8 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 18.1 | 190.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 79 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 85 | 87 | 85 | 85 | 82 | 80 | 79 | 81 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 0 (32) |

−1 (30) |

−1 (30) |

0 (32) |

3 (37) |

7 (45) |

9 (48) |

8 (46) |

7 (45) |

3 (37) |

1 (34) |

−1 (30) |

3 (37) |

| Source 1: Météo Climat (averages),[6] (records)[7] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Time and Date (humidity and dewpoints, 2005-2015)[8] | |||||||||||||

| Coastal temperature data for Vestmannaeyjar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 6.3 (43.34) |

6.5 (43.70) |

6.3 (43.34) |

6.7 (44.06) |

8.0 (46.40) |

9.3 (48.74) |

11.1 (51.98) |

11.6 (52.88) |

11.0 (51.80) |

8.7 (47.66) |

7.6 (45.68) |

6.9 (44.42) |

8.3 (47.00) |

| Source 1: Seatemperature.net[9] | |||||||||||||

History and name

The islands are named after Gaels who had been captured into slavery by Norsemen. The Old Norse word Vestmenn, literally "Westmen", was applied to the Irish, and retained in Icelandic even though Iceland is further west than Ireland. (In contrast, the Norse Gaels often called themselves Ostmen or Austmenn – "East-men".)

Not long after Ingólfr Arnarson arrived in Iceland, his blood brother Hjörleifr Hróðmarsson was murdered by the thralls he had brought with him. Ingólfur tracked them down to the Vestmannaeyjar and killed them all in retribution, hence the name Vestmannaeyjar (the islands of the west men). This is speculated to have occurred in AD 875.

On 16 July 1627, in an event known as the Turkish Abductions, the islands were captured by a fleet of three ships of Barbary Pirates from Algiers, who stayed there until 19 July under the control of Ottomans. They had earlier raided the east of Iceland and Murat Reis from Salé in Morocco had commanded another raid in Grindavík in June of that year. The pirates captured 234 people from the islands and took them on a 27-day voyage to Algiers, where most of them spent the rest of their lives in bondage.[10] One of the captives, Lutheran minister Ólafur Egilsson, managed to return in 1628 and wrote a book about his experience.[11] In 1636, ransom was paid for 34 of the captives, and most of them returned to Iceland. After this, a small fort was built on Skansinn (that is, "the bastion"), and an armed guard was established to keep watch from the mountain Helgafell for the approach of ships.

For centuries, the people of the Vestmannaeyjar had a hard struggle for existence, living from fishing and wild birds and their eggs, which they gathered in the cliffs and rock stacks offshore. At the end of the 19th century, when the population was about 600, great changes took place in the lifestyle of the islanders. In 1904, the first motorised boat was purchased, and more followed soon afterwards. By 1930, the population had risen to 3,470. The Vestmannaeyjar have always been at the forefront of developments in fishing and sea food processing, and are the most productive fishing centre in the country. Shortage of fresh water was also a problem for a long time, but a great improvement took place in 1968 when a pipeline was laid.

The area is very volcanically active, like the rest of Iceland. There were two major eruptions in the 20th century: the eruption in 1963 that created the new island of Surtsey, and the Eldfell eruption of January 1973, which created a 200-metre-high mountain where a meadow had been, and caused the island's 5,000 inhabitants to be temporarily evacuated to the mainland.

In 2000, Heimaey stave church, a replica of the Haltdalen Stave Church containing a replica of the St Olav frontal, was erected at Skansinn as a gift from the Norwegian government to Iceland, commemorating the conversion of Iceland to Christianity a thousand years before.[12]

Transportation

A ferry service runs from Landeyjahöfn (closer) and sometimes under bad conditions Þorlákshöfn (further away).[13] The new Landeyjahöfn harbour opened in 2010, shortening the sailing time to around 40 minutes.[14] A new hybrid electric ferry with a 3 MWh battery and capacity for 550 passengers and 75 cars started operating the 13 km route in July 2019.[15][16][17] It uses 100 MWh per week, replacing 35 tonnes of fuel. In bad weather, the longer route to Þorlákshöfn requires fuel.[18]

Vestmannaeyjar Airport was previously served by regular flights to Reykjavík, but as of 2023 there are no regular flights. Icelandair has served the airport with charter flights for the Þjóðhátið festival in 2022 and 2023.

Popular culture

Festival

The islands are famed in Iceland for their major annual festival, Þjóðhátíð ("The National Festival"), which attracts thousands of people. The festival was first held in 1874, at the same time as the commemoration of the millennium of the settlement of Iceland. Vestmannaeyjar residents had been prevented by bad weather from sailing to the mainland for the festivities and thus celebrated locally.[19]

Film

- From 1998 to 2003 the island of Heimaey was home to Keiko the killer whale, star of Free Willy (1993).

- The film The Deep (2012), based on true events, is set on and around the island.

Literature

- The islands and their history of volcanic activity play a major role in James Rollins' seventh Sigma Force novel, The Devil Colony (2011).[20]

- The islands feature as the primary location in Yrsa Sigurðardóttir's novel Ashes to Dust, which uses the 1973 eruption of Eldfell as a key element in the plot.

Sport

ÍBV, based on Vestmannaeyjar, are one of the most prominent sports clubs in Iceland, having won several national championships and national cups in both handball and football.

The Westman Islands Golf Club was established in 1938[21] and is located in the remnants of an extinct volcano. Golf Monthly ranks it as one of the top 200 golf courses in Europe.[22]

Notable people

- Ásgeir Sigurvinsson (born 1955), retired footballer, was born in Vestmannaeyjar and started his career at ÍBV

- Bergur Elías Ágústsson (born 1963), former mayor of Norðurþing, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Elísa Viðarsdóttir (born 1991), was born in Vestmannaeyjar and started her career at ÍBV

- Elsa Guðbjörg Vilmundardóttir (1932–2008), Iceland's first female geologist, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Fanndís Friðriksdóttir (born 1990), footballer from Vestmannaeyjar, training at ÍBV's youth programme

- Gísli Pálsson (born 1949), professor of anthropology, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Guðmundur Guðmundsson (1825–83), one of the first Mormon missionaries to preach in Iceland, preached in Vestmannaeyjar

- Guðmundur Torfason (born 1961), retired footballer, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Gunnar Heiðar Þorvaldsson (born 1982), footballer, was born in Vestmannaeyjar and has been signed to ÍBV on 3 occasions

- Halldóra Briem (1913–1993), the first Icelandic woman to study architecture, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Heimir Hallgrímsson (born 1967), manager of the Iceland national football team, was born in Vestmannaeyjar and has both played for and managed ÍBV teams on more than one occasions; he is still the dentist for the town

- Helgi Ólafsson (born 1956), chess grandmaster, is a native of Heimaey

- Hermann Hreiðarsson (born 1974), footballer, has been both player and player-manager at ÍBV

- Högna Sigurðardóttir (born 1929), architect, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Ívar Ingimarsson (born 1977), footballer and cousin of Gunnar Heiðar Þorvaldsson, played for ÍBV in 1998–99

- Júlíana Sveinsdóttir (1889–1966), painter and textile artist, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Kári Kristjánsson (born 1984), handball player, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Kolfinna Kristófersdóttir, model is originally from Vestmannaeyjar

- Marcellus de Niveriis OFM (died 1460 or 1462), bishop of Skálholt was master of the manor of Vestmannaeyjar

- Margrét Lára Viðarsdóttir (born 1986), retired footballer and is considered by many to be the best Icelandic female footballer of all times. Played for ÍBV, Valur and also played in Sweden and Germany. Scored 79 goals in 124 games for Iceland. Voted Icelandic athlete of the year 2007.

- Ólafur Egilsson (1564–1639), a Lutheran minister who, in 1627 with his wife and sons, was kidnapped in the Turkish Abduction, subsequently writing a memoir of his travels

- Sigurvin Ólafsson (born 1976), footballer, was born in Vestmannaeyjar and has twice been signed to ÍBV

- Smári McCarthy (born 1984), information activist and Icelandic Pirate Party MP, grew up in Vestmannaeyjar, his family having moved there when he was 9

- Sólveig Anspach (1960–2015), film director and screenwriter, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

- Tryggvi Guðmundsson (born 1974), footballer, was born in Vestmannaeyjar and started his career at ÍBV, returning there twice

- Þórarinn Ingi Valdimarsson (born 1990), footballer, was born in Vestmannaeyjar and started his career at ÍBV

- Þorsteinn Ingi Sigfússon (born 1954), award-winning physicist, was born in Vestmannaeyjar

See also

Notes

References

- "Westman Islands". Icelandic Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Population by urban nuclei, sex and age 1 January 2001-2022". PX-Web. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- Taylor Kate Brown (11 September 2014). "How do you stop the flow of lava?". BBC News. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "VESTMANNAEYJAR: Volcanic Activity". Nordic Adventure Travel. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- "An Icelandic Town Goes All Out to Save Baby Puffins". Smithsonian Magazine. March 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- "Météo climat stats for Vestmannaeyjar". Météo Climat. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "Météo climat stats for Vestmannaeyjar (records)". Météo Climat. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "Climate & Weather Averages in Vestmannaeyjar". Time and Date. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "Vestmannaeyjar Sea Temperature". seatemperature.net. 30 April 2023. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023.

- „Hvað gerðist í Tyrkjaráninu?". Vísindavefurinn, retrieved on 26 February 2012. (In Icelandic.)

- "The Travels of Reverend Ólafur Egilsson". Reisubok.net. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Paul Torvik Nilsen, 'Colourful Middle Ages', Tell'us: Science in Norway (December 2001), 6-9.

- "Ferry: Þorlákshöfn to Vestmannaeyjar". Visit Westman Islands - Ferry Herjólfur to Vestmannaeyjar. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Landeyjahöfn tekin í notkun". www.stjornarradid.is (in Icelandic). Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "ABB To Supply Drive & Energy Storage Technologies For New Electric Ferry". CleanTechnica. 5 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Herjólfur IV". Corvus Energy. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022.

- "Herjólfur". herjolfur.is. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021.

- Hafstað, Vala (28 November 2020). "Major Advantages to Running Ferry on Electricity". Iceland Monitor. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021.

- "The Festival". Visitvestmannaeyjar.is. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "The Devil Colony: A Sigma Force Novel". JamesRollins.com. p. 31.

- Daley, Paul (2008). Golf Architecture: A Worldwide Perspective, Volume 4. Pelican Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 9781589806160.

- "Vestman Island golf course". Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

External links

Vestmannaeyjar travel guide from Wikivoyage

Vestmannaeyjar travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website

- Info website about Vestmannaeyjar

- Vestmannaeyjar in the Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes

- Picture gallery from www.islandsmyndir.is

- Heimaey (the volcano)

- Travel site for Vestmannaeyjar

- Blog from Vestmannaeyjar

- Photos from Vestmannaeyjar