Westminster Psalter

The Westminster Psalter, British Library, MS Royal 2 A XXII, is an English illuminated psalter of about 1200, with some extra sheets with tinted drawings added around 1250. It is the oldest surviving psalter used at Westminster Abbey, and is presumed to have left Westminster after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It joined the Old Royal Library as part of the collection of John Theyer, bought by Charles II of England in 1678. Both campaigns of decoration, both the illuminations of the original and the interpolated full-page drawings, are important examples of English manuscript painting from their respective periods.

Description

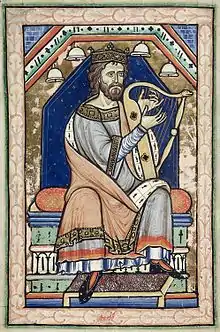

The manuscript has 224 medieval folios with a page size of 230 x 155 mm and a typical text area of 160 x 95. The binding is modern, from 1932. The contents begin with a calendar, illustrated with the signs of the Zodiac in small roundels (ff. 4r-10v), with Scorpio as a dragon. Then follow five full-page miniatures with gold grounds, showing: the Annunciation, Visitation, seated Virgin and Child, Christ in Majesty surrounded by the Evangelists' Symbols, and King David playing his harp (ff 12v-14v). David faces the large Beatus initial (f 15r) that begins the text of the Latin Book of Psalms, which includes three scenes from the life of David along the stem of the "B": David beheading Goliath, bringing his head to Saul, and harping, crowned as king. This occupies about two thirds of the page. The usual ten English sections into which the psalms are divided are marked by smaller decorated initials, some historiated with figures. These mark the start of Psalms 26 (f 38v), 38 (f 53r), 51 (f 66), 51 and 52 (f 66r and v), 68 with Jonah thrown off his ship, and riding on the whale (f 80v), 80 (f 98r), 97 (f 114r), 101 with Christ in the initial, and a kneeling monk below it with a scroll reading "Lord hear my prayer" (f 116), and 109 with the Trinity (f 132). The initials at the start of the other psalms are in coloured ink of red, green and blue, with decoration. Some of the decorative line-fillers have animal heads. The psalms are followed by the Litany, with the royal saint Edward the Confessor, who rebuilt Westminster Abbey, written in gold on f 182 (as he was in the calendar at f 5), and special prayers for Edward and Saint Peter, the abbey's dedicatee.[1]

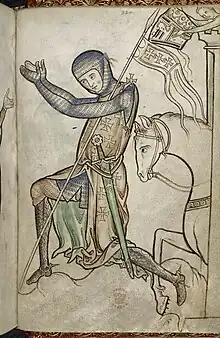

In about 1250 five tinted full-page drawings were added on previously blank pages (ff 219v-221v). These show: a king and a kneeling knight on facing pages, Saint Christopher carrying the Christ-Child, an archbishop, and finally the head of Christ in a format associated with images of the Veil of Veronica, with a prayer below referring to that relic. There were later additions of prayers and antiphons up to the 15th century, including a late 14th or 15th century drawing of a naked man.[2]

History

The manuscript is presumed to have been commissioned for Westminster Abbey by the monk who is shown at folio 116 (see above), who was perhaps William Postard, abbot from 1191 to 1200, or Ralph de Arundel, abbot from 1200 until "he was deposed for high-handedness" in 1214. According to one scholar, the calendar reflects changes "upgrading" some feasts that were introduced by Ralph as abbot, in terms of the markings reflecting the number of lessons to be read and copes to be worn, though stylistically a date as early as the 1180s would be possible.[3] The pattern of additions suggest it remained in use for services from its creation until the monastery was dissolved in 1540, and it appears in an inventory made in 1388 of the contents of the vestry, including 17 books used in services, as opposed to those in the library of the monastery,[4] as well as another inventory of 1540.[5] Like many monastic books, its history then becomes unclear for a period, before it reappears in the collection of the antiquarian bibliophile John Theyer (1597–1673), who made some notes in the book. After his death his collection was bought via the London bookseller Robert Scott for the Old Royal Library, which itself was given by George II to the newly founded British Museum in 1757.[6]

Recent writers such as Nigel Morgan are confident that all the 13th century illustration was produced in London, although the earlier full-page miniatures are by an itinerant master, which is reflected in Deirdre Jackson's catalogue entry for the British Library's 2011–12 Royal Manuscripts exhibition. However Janet Backhouse, then Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts at the British Library, described the prefatory miniatures as "England, possibly St Albans or Winchester" in a book of 1997, and the BL website used a similar formula in late 2011, though assigning the tinted drawings to "Westminster". Since the prefatory full-page miniatures are in a separate gathering their production may not necessarily have coincided exactly with that of the initials as regards either time or place, and they were "almost certainly created independently before being bound into the book".[7]

The clear and detailed depiction of the costumes of the figures in the tinted drawings has been discussed and copied in works on the history of costume since the late 18th century; in particular the sleeveless open-seam surcoat worn over chain mail of the kneeling knight is often used as an example of this innovation from the Islamic world.[8]

Style of the miniatures

Nigel Morgan was the first to distinguish a total of five hands in the decoration, three in the original campaign around 1200, one around 1250 and the last (naked man) later. The first artist did the roundels in the calendar, the Beatus initial, and the other figured initials, except for that with the monk on f 116, which was done by another artist. Between them these two were presumably responsible for the other decorated initials and text embellishments. These may well have been monks at Westminster, whereas the full-page prefatory miniatures were done by an artist of higher quality, who may well have been an "itinerant lay professional", as his work is also found in the initials in a bible made at St Albans Abbey, now at Trinity College, Cambridge (MS B. 5.3). His style is influenced by the artists responsible for the later work on the Winchester Bible, who are also thought to be responsible for the wall paintings in the chapter-house at Sigena in northern Spain, and those in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre in Winchester Cathedral.[9] The miniatures are on the cusp of Romanesque and Gothic painting. Morgan says of his style: "The figure forms are very substantial, static and rounded with fairly natural fold patterns. The faces are of Byzantine type but with softer modelling in lighter shades of colour resulting in more gentle expressions", and says his "Winchester training seems beyond doubt".[10]

The five tinted drawings added around 1250 are in a style especially associated with England, and best known through the contemporary work of Matthew Paris at St Albans, although it had been an English speciality since Anglo-Saxon times. A pen drawing with a strong outline is coloured with light brushed washes (the archbishop is in fact purely in ink, perhaps unfinished). They may be connected with a now lost psalter, also at Westminster and recorded in the inventory of 1388, which was said to have been given by Henry III (r. 1216–1272), who was rebuilding Edward the Confessor's abbey and also his Palace of Westminster at just this time. There are a number of documentary references to paintings in connection with the works on both buildings, now almost all lost.[11]

Like most English tinted drawings around this time, these were once attributed to Matthew Paris or his "St Albans school", but recent scholars see them as characteristic of a distinct London style: "The Westminster work has more detailed, refined faces, and contours and internal folds show more jagged effects of line. There is a sophisticated professionalism about the drawing which contrasts with Matthew's accomplished but somewhat naïve style".[12]

Iconography

The iconography of both campaigns of illustration has been related to the increasing assertion of royal power typical of the period. Meyer Schapiro pointed to very close similarities between some of the earlier miniatures and those in the slightly later Glazier Psalter, now Morgan Library & Museum, New York (MS G. 25), in particular in their miniatures of Christ in Majesty.[13] He analysed in the Glazier miniatures a programme related to the controversies over the balance between the power of monarchies and the Church that were very intense at this period, though finding the Glazier Psalter probably on the Church's side of the argument.[14] The Westminster miniatures lack some of the features that are distinctive in the Glazier Psalter, but the representation of the "sacred dynasty" of David, Mary and Jesus may still be significant, but "the idea is less clear-cut, less systematic, than in the later book".[15]

The grouping of the five tinted drawings is more unusual, since they combine the clearly devotional images of St Christopher and the Veronica face of Christ, with three figures from each of the Three Estates of contemporary society – the archbishop does not appear to represent a saint, despite being opposite St Christopher. The Veronica image was popular at this time, and appears in a number of English manuscripts,[16] but St Christopher was a newly popular saint in Northern Europe, and the Westminster drawing is "possibly his first isolated appearance in English art".[17]

The unusual drawing of the knight, with his horse and squire behind him, wearing crosses on his banner and surcoat, and kneeling to his king has been described as "a crucial representation not only of the relationship of mutual responsibility imposed by the feudal system, but also of the chivalric code of which the Christian king, especially in the Crusades, was the supreme exponent".[18] In an analysis of the changing role of the "new knighthood" of the 13th century,[19] another scholar cites the drawing as one of a number of examples from art showing "exalted notions of knighthood and its high moral purpose", and speculates that the king may represent Edward the Confessor, and the drawing be linked to Henry III taking the cross.[20] Henry became a "crucesignatus", signed up for the Crusades, on three occasions during his long reign, though he never in fact followed this through in person. The second occasion in March 1250, at a time when the campaigning of Louis IX of France in Egypt in the Seventh Crusade seemed about to achieve great successes, has puzzled historians since Matthew Paris, with many suggesting that Henry's main motive may have been either to claim a share of the great rewards of a conquest of Egypt, or alternatively to take control of the widespread enthusiasm for crusading that had seized the English military classes, with complicated political and financial implications for the crown.[21]

Henry's proposed expedition was accompanied by an artistic "propaganda" campaign, "apparently confined to 1251-52", which included the recorded painted decorations in the Antioch Chamber in Westminster Palace, showing the Siege of Antioch in 1098, the first great victory of the Crusades, and other works at Clarendon Palace and Winchester Castle. Of these the only surviving works, other than perhaps the drawing, are tiles from Chertsey Abbey, perhaps originally made for a royal palace, showing the combat of Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, among other scenes, and some at Westminster.[22] In 1254 Henry suggested that the rededication of the new Westminster Abbey be held on St Edward's feast-day in October 1255, before his planned embarkation; in fact he was diverted to settling unrest in his possessions in Gascony and, whatever his original intentions had been, never went further.[23]

Exhibitions

The manuscript is now not normally on display (though it was for considerable periods when in the British Museum), but has been exhibited in the British Museum, English Art 1934 and English book illustration, 966-1846 1965; Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, The Year 1200 1970, Hayward Gallery, English Romanesque Art 1066-1200 1984; Royal Academy of Art, Age of Chivalry: Art in Plantagenet England 1200-1400 1987. It was exhibited at the British Library in 2011–2012 in the exhibition Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination, displaying the opening at ff. 14v-15r with David facing the Beatus initial, which together with the drawings of the knight and the king, and the Annunciation and Visitation opening, has been the view most often exhibited.[24]

Notes

- Morgan, 49–50; BLC

- BLC, Royal, 118

- Pfaff, 231 (quoted), who analyses the calendar; Royal, 118; Morgan, 50

- Pfaff, 229; Royal, 118

- Morgan, 50

- Morgan, 50; Royal, 81

- Morgan, 50; Royal, 118 (quoted); Backhouse, 69; BLC; Thomson, 61

- BLC bibliography; Snyder, 84

- Royal, 118 (quoted); Morgan, 50, and no. 3, 51 for the Cambridge MS; Thomson, 61 on St Albans connections

- Morgan, 50

- Royal, 118; Alexander & Binski, 310-313 on Henry III's programme

- Alexander & Binski, 200 (entry by Nigel Morgan)

- Schapiro, 348–351; the Glazier Psalter is no. 50 in Morgan

- Schapiro, 340-348

- Schapiro, 331, 347, both quoted in turn

- Alexander & Binski, 200, though at Royal, 118, the drawings are described as comprising "Christ, various saints and a king"

- Wilson, 113

- Alexander & Binski, 196 (quoted), 200

- Coss, 136

- Coss, 137–138, which cites Alexander & Binsky (giving the wrong catalogue number) who do not mention these ideas, other than in the quotation earlier in this paragraph.

- Tyerman, 113-119

- Tyerman, 117 (quoted); Alexander and Binski, 181-182 and 204 (by John Cherry); the British Museum displays The Chertsey combat tiles

- Tyerman, 118

- BLC, and References section below for the catalogues for 1984, 1987 and 2011

References

- Alexander, Jonathan & Binski, Paul (eds), Age of Chivalry, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200-1400, no. 9, 1987, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Backhouse, Janet, The Illuminated Page: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Painting in the British Library, 1997, British Library/University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-7123-4542-2

- "BLC": British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts (online), Detailed record for Royal 2 A XXII, accessed 14 December 2011, with a large bibliography

- Coss, Peter R., The Origins of the English Gentry, 2005 reprint, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-02100-6, ISBN 978-0-521-02100-5, google books

- "Royal": McKendrick, Scot, Lowden, John and Doyle, Kathleen, (eds), Royal Manuscripts, The Genius of Illumination, no. 12, 2011, British Library, 9780712358156

- Morgan, Nigel, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, Volume 4: Early Gothic Manuscripts, Part I 1190-1250, no. 2, Harvey Miller Ltd, London, 1982, ISBN 0-19-921026-8 (also no. 95 in Part II, for the tinted drawings)

- Pfaff, Richard W., The Liturgy in Medieval England: A History, 2009, Cambridge University Press, google books

- Schapiro, Meyer, "An Illuminated English Psalter of the Early Thirteenth Century", in Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art: Selected Papers, 1980 (first publ. 1960), Chatto & Windus (or New York: George Braziller), ISBN 9780701125141 *Snyder, Janet, "Costumes in the Portfolio of Villard", in Marie-Thérèse Zenner, Jean Gimpel, eds., Villard's legacy: studies in medieval technology, science, and art in memory of Jean Gimpel, 2004, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-0929-4, ISBN 978-0-7546-0929-2, google books

- Thomson, Rodney M., Manuscripts from St Albans Abbey 1066-1235, 2 vols, 1982, Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, google books

- Tyerman, Christopher, England and the Crusades, 1095-1588, 1996 edn., University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-82013-0, ISBN 978-0-226-82013-2, google books

- Wilson, Christopher, Westminster Abbey, 1986, Bell & Hyman

- Zarnecki, George and others; English Romanesque Art, 1066-1200, no. 82, 1984, Arts Council of Great Britain, ISBN 0-7287-0386-6

External links

- British Library, Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts blog, 5 July 2011