Wheeler's Surprise

Wheeler's Surprise, and the ensuing Siege of Brookfield, was a battle between Nipmuc Indians under Muttawmp, and the English colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Colony under the command of Thomas Wheeler and Captain Edward Hutchinson, in August 1675 during King Philip's War.[1] The battle consisted of an initial ambush by the Nipmucs on Wheeler's unsuspecting party, followed by an attack on Brookfield, Massachusetts, and the consequent besieging of the remains of the colonial force. While the place where the siege part of the battle took place has always been known (at Ayers' Garrison in West Brookfield), the location of the initial ambush was a subject of extensive controversy among historians in the late nineteenth century.[2]

| Wheeler's Surprise and Siege of Brookfield | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of King Philip's War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Nipmuc |

Praying Indians Mohegan | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Muttawmp Matoonas |

Cpt. Thomas Wheeler Cpt. Edward Hutchinson Maj. Simon Willard | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown, but at least a hundred | Originally 35-40 men were ambushed, remains plus about 70 civilian colonists were besieged. Relief force numbered 350 colonial militia plus an unknown number of Mohegan Indians. | ||||||

Background

After the death of the pro-English Massasoit in 1661, his son Metacom, known to the English colonists as "King Philip" initiated contacts with sachems of various tribes of New England to unite against the interests of the Plymouth Colony. The actual outbreak of war occurred on June 20, 1675, when a band of Pokanoket (a tribe of the Wampanoags) launched an attack on Swansea, Massachusetts, most likely without Metacom's approval, in retaliation for an earlier killing of a Pokanoket by an English colonists.[3] In response, the colonists attacked and burned a Pokanoket village at Mount Hope.[4]

Simultaneously the colonists sent Ephraim Curtis to the west of Boston into Nipmuc territory to negotiate with the tribe and obtain assurances of loyalty from them.[5] However, Curtis' expedition party found only empty Nipmuc villages which signified that something was already afoot. Eventually, Curtis managed to find the whereabouts of the Nipmuc chief sachem, Muttawmp, and agreed to a meeting at a pre-arranged spot.[5] However, unbeknownst to Curtis it was too late for negotiations, as the Nipmucs, under sachem Matoonas, had already attacked an English colonial settlement at Mendon and had decided to join Metacom's rebellion.[6] Curtis was later joined by Captain Thomas Wheeler and Captain Edward Hutchinson (son of Anne Hutchinson).

Negotiations

Curtis and his men met with the Nipmuc sachem Muttawmp on July 14, the same day that another party of Nipmuc warriors was attacking Mendon. Hence, at the meeting, Muttawmp already considered himself to be at war with the English colonists. However, while Muttawmp's soldiers were rude to the English emissaries, the sachem himself considered it better to feign friendship to the colonists and so told Curtis that he would show himself in Boston within seven days.[7]

After Curtis returned to Boston and informed his superiors of the arrangement, a decision was made not to wait for Muttawmp's arrival, but instead to send Captain Hutchinson, along with Captain Wheeler and 30 mounted militia, as well as some "Natick" Praying Indian guides to negotiate with the Nipmuc sachem directly.[7] The party made their way to New Norwich where, on July 31, they found the village empty. Consequently, they learned that the Nipmucs had moved their base camp to about 10 miles (16 km) from Brookfield, and sent Curtis and the Naticks to talk to Muttawmp again. There, the emissaries were once again treated rudely by the Nipmuc braves, while Muttawmp continued his deception and agreed to meet Hutchinson in Brookfield on the following day.[7]

Ambush

However, when the colonists arrived in full force at the agreed spot the next day they found nothing. At that point the Natick guides tried to persuade the colonists to give up and return to Brookfield. Hutchinson and Wheeler, however, decided to march on to the Nipmuc camp, where they had met them the previous day.[8]

In order to reach Muttawmp's camp, the colonists had to cross a swamp, taking a narrow path in single file. Despite more protestations from the Indian guides, Hutchinson and Wheeler decided to risk it, while at the same time aware that they might be walking into a trap.[8]

In fact, after they proceeded for about 400 yards (370 m), Muttawmp's braves emerged from among the tall swamp grass and attacked them with bows and rifles. When the colonists turned around and tried to flee along the narrow path, they encountered another group of Nipmucs blocking their retreat.[8] The colonial force was so completely disorganized that initially they were not even capable of returning fire. Both Hutchinson and Wheeler were seriously wounded. Eight other men were killed in the initial attack and several others were wounded.[8]

The entire force would have most likely been annihilated there and then had it not been for the Natick guides, one of whom assumed command of the company in place of the wounded captains, and managed to lead the rest of the colonists out of the trap and into the hills near the swamp.[9] Once out of immediate danger, the group made its way to Brookfield, fully aware that Muttawmp was in pursuit.[9]

Siege of Brookfield

Wheeler and the rest of his men, led by the Natick guides, fled to the English colonial settlement of Quabaug (which later was to become the town of West Brookfield). The village was relatively isolated which meant that no help was coming soon, even if the colonists in other New England towns got word of the attack.[10]

At Brookfield, the militia gathered at the house of Sgt. John Ayers (who had been killed in the ambush) and there they were joined by about 70 villagers who had learned of the coming Nipmuc attack. Ayers' garrison was the largest building in the settlement.[11] Once inside the house, Wheeler recovered from shock and took charge of his men again, and ordered them to fortify the defenses. He tried to send two militiamen to get help, but they did not leave before the arrival of Muttawmp and his warriors.[9] In all about 80 persons had gathered inside the Ayers house.[11]

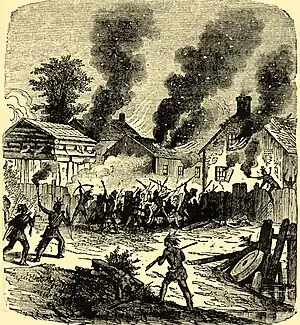

When they arrived at the scene, some of the Nipmucs kept the garrisoned house under constant fire, while others drove off the livestock, looted other houses in the settlement, and then set them on fire. Once Muttawmp had gathered all his men and completely surrounded the house he launched three attacks on the Ayers house. All three were unsuccessful and the only English casualties that occurred on the first day were two colonists who made the mistake of stepping outside and who were quickly killed. As a result, Muttawmp realized that he needed a different approach.

On the second day of the siege, early at dawn, Muttawmp had his men fill a village wagon with combustible material and direct it at the fortified house, hoping to set it on fire and in that way force the defenders out. However, the plan did not work because of heavy rains which began to pour while the wagon was in preparation. During the confusion that accompanied the execution of the plan, Ephraim Curtis managed to sneak out of the house and made a successful run for the woods. He eventually made it to Marlborough although by that time the colonial militia had already been alerted by some travelers who had heard gunfire near Brookfield. As a result, a group of men under Major Simon Willard were already on their way to relieve the besieged.[12]

Relief

Simon Willard, who was the chief military officer of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, with 48 troops had been stationed at Lancaster. After being informed of the siege he hurried to Brookfield, arriving on the night of the 3rd. This forced the Indians to break off the siege. Further reinforcements continued to arrive, and Willard eventually commanded 350 colonial militiamen and an unknown number of Mohegan Indian allies.[13]

The battle between the two sides continued until the middle of the night of the 4th but neither side could dislodge the other. At that point, Muttawmp, who felt he had already achieved most of what he wanted (including obtaining crucial supplies from the looting of Brookfield), decided that he did not want to risk the death of any more of his warriors and withdrew from the battlefield.[12]

Aftermath

After withdrawing from Brookfield, Muttawmp led his men to a fort at Hatfield. Metacom himself, with 40 Wampanoag warriors, arrived there a short while later. King Philip, hearing of the attack, rewarded the Nipmuc sachems with unstrung wampum.[14]

The next attack by the Indians took place at South Deerfield, in August of the same year. Throughout the rest of the 1675, the Native American forces had a string of victories, thanks in large part to skillful leadership of sachems like Metacomet, Muttawmp and Matoonas, who exploited their knowledge of local terrain to achieve surprise and often successfully ambushed colonial forces sent to track them down, much in the same way as happened in Wheeler's Surprise. However, 1675 ended with a significant defeat for the Native Americans, with the defeat of the Narragansetts in the Great Swamp Fight.

While Philip and his allies managed to regain the initiative for some time in 1675, eventually the scorched-earth tactics practiced by the colonists caused them to start running out of supplies. The supply shortage, coupled with a partial amnesty, prompted an increasing number of chiefs to leave Philip's alliance. Others, like Narragansett chief Canonchet, were killed. In the spring of 1676 the tide turned in favor of the colonist.[15] Muttawmp, the victor of Brookfield, tried to make peace with the colonial authorities. Promises of safety were broken however, and he was executed in September 1676. The leader of the uprising, Metacomet, had already been isolated, surrounded in the Assowamset Swamp and killed by a Praying Indian on August 12 of the same year.[16]

Legacy

A marker on Massachusetts Route 9 on the boundary of Brookfield commemorates the event:

BROOKFIELD.

SETTLED IN 1660 BY MEN FROM

IPSWICH ON INDIAN LANDS CALLED

QUABAUG. ATTACKED BY INDIANS

IN 1675. ONE GARRISON HOUSE

DEFENDED TO THE LAST. REOCCUPIED

TWELVE YEARS LATER.

The eponymous Thomas Wheeler of "Wheeler's Surprise" survived the battle and shortly afterwards wrote an account of it, which was first published in 1676.[18]

The episode is also notable for the fact that it was a subject of academic controversy among 19th-century historians. The main topic of contention was the precise location of where the ambush - the Wheeler's Surprise - took place, and the exact path of Wheeler and Hutchinson's march.[19] While the exact location still remains a mystery, the most likely site of the ambush according to modern historians lies somewhere within the present day town of New Braintree, Massachusetts.[19]

References

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 147

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 151

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 39

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 40

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 41

- Bonfanti, pg. 26

- Bonfanti, pg. 27

- Bonfanti, pg. 28

- Bonfanti, pg. 29

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 156

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 157

- Bonfanti, pg. 30

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 158

- Bonfanti, pg. 31

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 59-61

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 68-69

- Schultz and Tougias, pg. 160

- Trent, pg. 99

- Schultz and Tougias, pgs. 151-155

Works cited

- Eric B. Schultz, Michael J. Tougias, "King Philip's War. The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict", Countryman Press, 1999.

- Leo Bonfanti, "Biographies and Legends of the New England Indians", New England Historical Series, Pride Publications, 1981.

- William Peterfield Trent, "Colonial prose and poetry, Volume 2", T. Y. Crowell & co., 1903

- James D. Drake, "King Philip's War. Civil War in New England, 1675-1676", University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, 1999