Whistleblower protection in the United States

A whistleblower is a person who exposes any kind of information or activity that is deemed illegal, unethical, or not correct within an organization that is either private or public. The Whistleblower Protection Act was made into federal law in the United States in 1989.

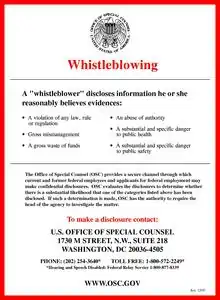

Whistleblower protection laws and regulations guarantee freedom of speech for workers and contractors in certain situations. Whistleblowers are protected from retaliation for disclosing information that the employee or applicant reasonably believes provides evidence of a violation of any law, rule, regulation, gross mismanagement, gross waste of funds, an abuse of authority, or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety.[1]

Law

The law covering whistleblowers falls under the category of Public law.

Public law

Public law governs the relationship between people and the state and comprises three types: constitutional law, criminal law, and administrative law. Constitutional law governs the principles and the powers of the government and the relationships between the different parts of the government. Criminal law restricts conduct that threatens safety and welfare of society or the state. Administrative law regulates the operation and the procedures of government agencies. The judicial branch of government interprets the laws, and its body of laws is called case law.

Administrative

Excluding uniformed military, about 65% of federal government workers are employed within the executive branch,[2] and they are subject to orders and regulations issued by the President called executive orders as well as regulations issued by administrative authorities acting under the President and codified under Title 5 of the Code of Federal Regulations as follows:

- EO 12674 - Principles of Ethical Conduct for Government Officers and Employees[3]

- 5 C.F.R. Part 2635, as amended at 81 FR 48687 - Standards of Ethical Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch[4]

- EO 12356 - National Security Information[5]

Whistleblower protection laws for the military:

- SECNAVINST 5370.7C: Military Whistleblower Reprisal Protection[6]

- 10 U.S.C. 1034 Military Whistleblower Act[7]

- Department of Defense Directive[8]

Other organizations that provide similar information:

- Health and Human Services[9]

- Department of Homeland Security[10]

- US Air Force[11]

- US Army[12]

- US Department of Defense[13]

- US Marine Corps[14]

- US Marshals Service[15]

- US Navy[16]

Senior officers who fail to act on information regarding crime or incompetence are subject to a permanent reduction in rank or court-martial. Civilians who occupy senior pay grades have similar requirements and restrictions.

States are organized in much the same way, and governors issue executive orders.[9]

Criminal

Hazardous chemical exposure provides an example of whistleblower action.

Disclosure and product safety are the difference between legal insecticide application and assault with a deadly weapon.

In most areas, the law requires physicians to file a report for "Any person suffering from any wound or other physical injury inflicted upon the person where the injury is the result of assaultive or abusive conduct."[17] Mandated reporters are obligated to submit a report to a local law enforcement agency as follows.

- The name and location of the injured person, if known.

- The character and extent of the person's injuries.

- The identity of any person the injured person alleges inflicted the wound, other injury, or assaultive or abusive conduct upon the injured person.

Employers must inform and train employees before insecticide exposure to avoid criminal prosecution that could occur in addition to workers' compensation obligations when the employee consults a physician.

In United States common law, non-criminal battery is "harmful or offensive" contact resulting in an injury that does not include intent to commit harm. This is called tortuous battery, and this falls into the same category as automobile accidents which are handled with workers' compensation. This is applicable even if there is a delay between the harmful act and the resulting injury.[18][19]

The definition of criminal battery is (1) unlawful application of force (2) to the person of another (3) resulting in bodily injury. For example, an employer commits a crime if they fail to disclose insecticide exposure in accordance with public law (unlawful force) then subsequently violates the product labeling in the assigned work area (to the person), resulting in permanent disability (bodily injury).[20]

Insecticide injury is an accident and not a crime if EPA is informed, employees are adequately trained before exposure, and products are correctly labeled. Similar principles apply to rental property occupants, occupants of public buildings like schools, and customers exposed by a business owner.

Criminal penalties also exist within the Sarbanes–Oxley Act regarding company finance.

Financial irregularities involving Misappropriation is one area where criminal penalties apply to federal managers. Funds allocated by Congress for one purpose may not be spent for a different purpose, including payroll. The U.S. Navy[21] provides an example.

Title 18, United States Code, Section 1001 establishes criminal penalties for false statements. This applies to false statements exchanged between federal employees, including managers, appointed officials, and elected officials.

Criminal penalties also apply when crimes occur in the workplace, as is often the case with an injury. For example, an illness that results after workplace exposure to hazardous substances requires medical evaluation. For the evaluation, access to the product's safety data sheet that contained the hazardous substance is required, as well as verification of workers compensation. Failure to post mandatory information is a crime.

Retaliation remedies are limited to withholding payroll from the manager and civil remedies that involve the Civil Service Reform Act.

State laws are also applicable to federal workers, and California provides an example.

- California Labor Code Section 6425[22]

State law

Some states have statutes regarding whistleblowing protections, for example, New York.[23] A school nurse who was fired due to mandated reporting[24] of a single case of child abuse that was allegedly "covered up," could seek protection under New York law.[25][26]

U.S. labor law and policy

Employer activity that is not prohibited by law is usually permitted. Ignorance of the law does not make something legal. Managers cannot order people to participate in situations involving something that is illegal, unethical, or unhealthful. When a worker feels that this is the case, they may file a dispute. Workers will often prevail if some kind of law or public policy can be used to justify a dispute. When a dispute goes to grievance, then laws and policies need to be cited, otherwise, the dispute may fail.

The Prohibited Personnel Practices Act amended United States Code, Title 5: Government Organization and Employees to provide federal employees with whistleblower protection. The law forbids retaliation for whistleblowing.

One of the more pressing concerns is workplace safety. Failure to satisfy building codes established by the International Code Council can have a negative impact on occupational safety. Buildings constructed before 1990 probably do not satisfy these requirements.

As an example, managers may not recognize the reason for elevated illness rates when fresh air ventilation for the building is shut down. The building no longer satisfies OSHA laws and building codes without fresh air. EPA recommends fresh air exchange of no less than 15 cfm/person to prevent the accumulation of toxic chemicals in the air, like the carbon dioxide that is exhaled in human breath. Inadequate fresh air will cause illness or death due to excess buildup of toxic gasses inside buildings.

Building codes applicable to most areas of the United States are as follows:

Supreme Court

The US Supreme Court has limited whistleblower protections for public disclosures based on free speech for most government workers. Garcetti v. Ceballos held that the First Amendment does not apply to situations that fall within the scope of the job description associated with the employment of each government worker. The Supreme Court decision means that government management may discipline government employees who publicly disclose crime and incompetence under certain circumstances.

Job-related functions are supposed to be disclosed to management by grievance to the Inspector General, to the [Office of Special Counsel], to appointed officials, or to elected officials.

Issues that exist outside the job-description are not prohibited by Garcetti v. Ceballos. Public disclosure of the work environment not related to work assignments does not compromise essential functions like national security and law enforcement. In theory, criminal penalties apply to managers that discipline employees for public disclosure of situations outside the job description.

The following are some examples of situations outside the job description.

- Undisclosed hazardous material exposure when the hazard is not in the job description

- Unauthorized acceptance of defective goods or services when the defect is not associated with the job description

- Sexual harassment, racial discrimination, slander, and stalking

- Failure to provide meals, breaks, and rest time

- Compulsory work assignments without pay.

Disclosing misconduct, free speech and retaliation

Federal and state statutes protect employees from retaliation for disclosing other employee's misconduct to the appropriate agency.

The difficulty with the free speech rights of whistleblowers who make their disclosures public, particularly those in national defense, that involve classified information can threaten national security.

Civilian employees and military personnel in the intelligence gathering and assessment field are required to sign non-disclosure agreements, a practice upheld by the Supreme Court in Snepp v. United States. Courts have ruled that secrecy agreements circumscribing an individual's disclosure of classified information did not violate their First Amendment rights. Non-disclosure agreements signed by employees create similar conflicts in private business.

The United States Office of Special Counsel provides training for the managers of federal agencies on how to inform their employees about whistleblower protections, as required by the Prohibited Personnel Practices Act (5 USC § 2302). The law forbids retaliation for whistleblowing. (See: U.S. Labor Law and Policy above.)

Acts

False Claims Act of 1863

The False Claims Act (a.k.a.: the Lincoln Law) states details describing the process of an employee who files a complaint that turns out not to be valid. Congress enacted the law to provide a legal framework to deal with military contractors engaged in defrauding the federal government. This fraud occurred through either the overcharging of products or providing defective war material, including food and weapons.[28] The original issue that spurred Congressional action was the sale of defective cannons. These cannons were known to blow up and cause casualties among Union troops.

This law specifies that the employee filing the complaint can be held accountable for a false claim if they knew their claim was invalid to begin with when they decided to file it. If it is found that the person knew what they were claiming was untrue, then they are liable for no less than double the damages. The law provides for civil, but not criminal, penalties and provided a financial incentive for whistleblowers. The incentive equals 15 to 30 percent of the money recovered, which can amount to millions of dollars.[29][30] In addition to financial compensation, the False Claims Act offers limited protection for workers who provide tips about defective products and services delivered to the U.S. government. This prohibits firing the employee who provided the tip. The statute of limitations may span six years.

The False Claims Act provides civil remedies for non-government workers. Qui tam is a provision under the False Claims Act that allows private individuals to sue on behalf of the government. Separate remedies are available for government workers. This False Claims Act helps to make sure claims are truthful, accurate, valid, and fair. If every employee filed a complaint just to file a complaint and be compensated for it, it would not be very reliable or fair.[31]

Lloyd–La Follette Act of 1912

The Lloyd–La Follette Act was passed in Congress in 1912 to guarantee the right of federal employees to communicate with members of Congress. The bill was the first to protect whistleblowers. It established procedures for the liberation of federal employees from their employer and it gave them the right to join unions.

The act states that "the right of employees ... to furnish information to either House of Congress, or to a committee or Member thereof, may not be interfered with or denied." This legislation prohibits payroll compensation for managers who retaliate against employees who attempt to provide whistleblower disclosure (pay to the manager is suspended).

The intent is to provide direct feedback to Congress from federal employees, most of whom work within the executive branch.

This does not provide protections for employees who violate disclosure rules associated with unauthorized classified information disclosure and other types of unauthorized public disclosure associated with issues like law enforcement investigation and juvenile records. Unauthorized disclosures of classified information are prohibited, so job-specific issues should be disclosed to the appropriate legislative committee, where members should hold the appropriate clearance.

As a general rule, Lloyd–La Follette disclosures should cover a topic that will benefit the government if the issue could be resolved by Congressional involvement when the resolution would not be supported as a beneficial suggestion and would be opposed by management.[32]

Freedom of Information Act of 1966

The Freedom of Information Act of 1966 can provide access to information required to pursue a whistleblower action. FOIA provides the public the right to request access to records from any federal agency. It is often described as the law that keeps citizens in the know about their government. Federal agencies are required to disclose any information requested under the FOIA unless it falls under one of nine exemptions which protect interests such as personal privacy, national security, and law enforcement.

The nine exemptions are as follows:

- Exemption 1: Information that is classified to protect national security.

- Exemption 2: Information related solely to the internal personnel rules and practices of an agency.

- Exemption 3: Information that is prohibited from disclosure by another federal law.

- Exemption 4: Trade secrets or commercial or financial information that is confidential or privileged.

- Exemption 5: Privileged communications within or between agencies, including:

- Deliberative process privilege

- Attorney-work product privilege

- Attorney-client privilege

- Exemption 6: Information that, if disclosed, would invade another individual's personal privacy.

- Exemption 7: Information compiled for law enforcement purposes that:

- a) Could reasonably be expected to interfere with enforcement proceedings

- b) Would deprive a person of a right to a fair trial or an impartial adjudication

- c) Could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy

- d) Could reasonably be expected to disclose the identity of a confidential source

- e) Would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions

- f) Could reasonably be expected to endanger the life or physical safety of any individual

- Exemption 8: Information that concerns the supervision of financial institutions.

- Exemption 9: Geological information on wells.[33]

The FOIA also requires agencies to proactively post online certain categories of information, including frequently requested records.

As an example, the use of hazardous chemicals must be disclosed to employees, such as pesticides. Injury due to hazardous chemical exposure, radiation, and other hazards permanently disable 100,000 federal workers each year. Notification of hazardous chemical exposure is also required by Right to know. Right to know is necessary for workplace safety involving things like chemical injury, radiation injury and other occupational illnesses where the cause may not be discovered by physicians without disclosures that are required by law. Workplace hazards must be prominently displayed and public hazards must be disclose to state and county agencies.

A FOIA request is the most valuable law that supports Whistleblower actions when a Right to know violation has occurred. This kind of request cannot be made anonymously and fees may be required. There may be an advantage if the request is made through an unrelated individual, such as a union official or another member of the community. Right to know is just one example of many reasons why an FOIA request may be needed to pursue a whistleblower action.[34]

Civil Service Reform Act of 1978

The Civil Service Reform Act was the second protection adopted, but it gave protections only to federal employees. Later, the [Whistleblower Protection Act] of 1989 would provide protections to those individuals who work in private-sectors. Government workers who experience retaliation as a result of whistleblower retaliation may pursue defense against those actions under the authority of this Act. This established the following organizations to manage the federal workforce within the executive branch of government:[35]

- Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB)[36]

- Office of Personnel Management (OPM)[37]

- Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA)[38]

These cover most of the three million federal workers within the United States.

The MSPB is a quasi-judicial organization with enforcement authority for prohibited personnel actions. MSPB is also responsible for reimbursing legal fees in some situations.

Issues that involve discrimination and harassment are pursued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. This may include failure to accommodate disability, in addition to inequities involving gender or race.

Federal workers are entitled to financial benefits.[39] Thus, a whistle-blower action should include a beneficial suggestion to reserve the right to potential financial compensation for job-related improvement suggestions.

- Defense Efficiency[40]

- U.S. Air Force[41]

- U.S. Army[42]

- U.S. Marines[43]

- U.S. Navy[44]

- White House[45]

Other remedies may be available if a federal worker is unable to return to work. Employees with over five years' government service may be eligible for early retirement if medical records support a finding of disability not accommodated in accordance with the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Retirement rules are listed in the OPM Retirement Settlement Guide. Early retirement due to medical disability affects about 100,000 federal workers every year.

There are two retirement systems:

The FLRA is an independent administrative federal agency covering certain collective bargaining rights (unions). Postal employee collective bargaining is covered by the Postal Reorganization Act under the United States Postal Service.[48]

Ethics in Government Act of 1978

The U.S. Office of Government Ethics[49] is the supervising ethics office for the executive branch.[50]

Supervising ethics offices for other branches of government are as follows.

- Senate Select Committee on Ethics[51]

- House Committee on Standards of Official Conduct[52]

- Judicial Conference Committee on Codes of Conduct[53]

The Ethics in Government Act of 1978 was put in place so that government officials have their salaries put on public record for all to see. This was a result of the Nixon Watergate scandal and the Saturday Night Massacre. It created a mandatory, public disclosure of financial and employment history of government officials and their immediate family members for the regular U.S. citizen to have access to view. For example, if you were working within public service, your salary and other financial information relating to your job becomes public record within 30 days of becoming hired by the government.

The Ethics in Government Act provides three protections that apply to whistleblowers. They are as follows:

- Mandatory, public disclosure of financial and employment history of public officials and their immediate family.

- Restrictions on lobbying efforts by public officials for a set period of time after leaving public office.

- Creates the U.S. Office of Independent Counsel (OIC)[54] to investigate government officials.

The U.S. (OIC)[54] deals with ethical rules that cover all government employees and the OIC is responsible for documenting the whistleblower process.

One whistleblower caution is that political activity is prohibited by government employees. Whistleblower contact with elected or appointed officials must include no references to political support, political opposition, and campaigns.

Another caution is that whistleblowers who have to leave government employment are given time limits that prohibit employment by entities where the government employee was responsible for any contractual interactions. The former government employee may be prohibited from interacting in an official capacity directly with former coworkers who are still employed by the government.[57]

Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989

The Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989 was enacted to protect federal employees who disclose "Government illegality, waste, and corruption" from adverse consequences related to their employment.[58] This act provides protection to whistleblowers who may receive demotions, pay cuts, or a replacement employee. There are certain rules stated in this act that are civil protection standards against voidance of dismissal, voidance of cancellation of worker dispatch contracts, and disadvantageous treatment (i.e. demotion or a pay cut). The court judges what is considered valid or not for each complaint filed for dismissal or cancellation.

However, there are certain limitations to the Protection Act. For example, this act does not cover tax laws or regulate money used in political activities. It is in these political campaigns where whistleblowing is more effective in comparison to other organizations. Whistleblowers are required to present information and other documents that can back up their claims when filing a dispute. If it is found that they are lying, they may be subjected to criminal charges.

The Supreme Court has ruled this protection only applies to government workers when the disclosure is not directly related to the job. The U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) uses agency lawyers in the place of "administrative law judges" to decide federal employees' whistleblower appeals. These lawyers, dubbed "attorney examiners," deny 98% of whistleblower appeals; the Board and the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals give great deference to their initial decisions, resulting in affirmance rates of 97% and 98%, respectively.[59] Whistleblower Protection does not always protect federal workers. The Supreme Court ruling excludes whistleblower actions covered in the job description for federal workers. Job related issues must go through the hierarchy of the organization. When that fails, the issue must be brought to the attention of MSPB, EEOC, or OPM if it impacts employment. Unclassified issues not directly related to the job that in turn do not have a negative impact on national security or law enforcement may be suitable for public disclosure. Public disclosure would cover things like sexual harassment, racism, stalking, slander, and pesticide exposure, if you are not employed as an exterminator.[60][61] Crimes involving public transportation or federal employees should be disclosed to the Inspector General for Department of Transportation.[62][63][64]

Although the Whistleblower Protection Act has some limitations, its main goals are to help eliminate corporate scandals and promote agreements in companies that coordinate with other legislations.

No FEAR Act of 2002

The No Fear Act stands for Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act and was made effective in 2002. It discourages federal managers and supervisors from engaging in unlawful discrimination and retaliation and holds them accountable when they violate antidiscrimination and whistleblower protection laws. It was found that agencies cannot be run effectively if federal agencies practice or tolerate discrimination. The main purpose is to pay awards for discrimination and retaliation violations out of the agency budget.

Employer obligations under the No FEAR Act are as follows (requires annual training):[65]

- Notify federal employees, former federal employees, and applicants for federal employment about their rights under the Federal Antidiscrimination, Whistleblower Protection, and Retaliation Laws

- Post statistical data relating to Federal sector equal employment opportunity complaints on its public website

- Ensure that managers have training in the management of a diverse workforce, early and alternative conflict resolution, and essential communications skills

- Conduct studies on the trends and causes of complaints of discrimination

- Implement new measures to improve the complaint process and the work environment

- Initiate timely and appropriate discipline against employees who engage in misconduct related to discrimination or reprisal

- Reimburse the Judgment Fund for any discrimination and whistleblower related settlements or judgments that reach in Federal court

- Produce annual reports of status and progress to Congress, the Attorney General, and the U.S. Equal Employment Commission

Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002

The Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 was established to assist in the regulation of financial practice by corporate governance. It was devised by Congress to help with deficiencies in the business environment. This law was made in response to the failure of other laws that resulted in bankruptcy and fraudulent accounts. It was made to help regulate businesses to not commit fraud. Federal provisions were made in addition to state laws, which provided a balance in state and federal regulations in the business industry.

It established mandatory whistleblower disclosures, under certain circumstances, if mandated reporters fail to disclose, that could result in criminal penalties. This requires registration and accurate reporting for funding instruments, like stocks and bonds used to finance private industry. Some corporate officers are required to report irregularities (mandated reporters).[66]

Whistleblower disclosures involving securities and finance should be made to the Securities and Exchange Commission,[67] the state attorney general,[68] or the local District attorney.[69]

National security protections

The whistleblower laws and executive orders that specifically apply to U.S. intelligence-community employees include the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act of 1998 (ICWPA), Presidential Policy Directive 19, and the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014.[70] National security whistleblowers do not currently have court access to challenge retaliation. The current system for enforcing intelligence-community whistleblowers' rights against reprisal is entirely internal; however, the Congressional, intelligence committees can intervene to help ensure that the whistleblower is protected, and an appeals mechanism was added in recent years. Under this framework, intelligence- community whistleblowers are not protected from retaliation if they raise "differences of opinions concerning public-policy matters," but are protected if they raise violations of laws, rules, or regulations. This makes it difficult for national-security employees to raise questions about the overarching legality or constitutionality of policies or programs operated under secret law, like the NSA's mass-surveillance programs.[70]

The Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act (ICWPA) was passed in 1998. This law provides a secure means for employees to report to Congress allegations regarding classified information. The law, which applies to both employees and contractors, requires the whistleblower to notify the agency head, through an Inspector General, before they can report an "urgent" concern to a Congressional intelligence committee. The law doesn't prohibit employment-related retaliation, and it provides no mechanism, such as access to a court or administrative body, for challenging retaliation that may occur as a result of having made a disclosure.[70]

In October 2012, Barack Obama signed Presidential Policy Directive 19,[71] after provisions protecting intelligence-community whistleblowers were stripped from the proposed Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act. It was designed to ensure that employees who serve in the Intelligence community, or have access to classified information, can effectively report waste, fraud, and abuse, while protecting classified information. The order prohibits retaliation against intelligence community employees who make a protected disclosure through the proper, internal channels and establishes remedies for substantiated, retaliation claims. The directive requires each intelligence-community agency to establish policies and procedures that prohibit retaliation and to create a process through which the agency's Inspector General can review personnel or security clearance decisions alleged to be retaliatory. The directive also creates a process by which a whistleblower can appeal an agency-level decision regarding a retaliation claim to the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community, who can then decide whether or not to convene a review panel of three inspectors general to review it. The panel can only make recommendations to the head of the original agency where the complaint was first lodged and cannot actually require agencies to correct it.

PPD-19 does not protect contractors from any form of reprisal except decisions connected to their security clearance, which leaves them open to retaliatory terminations, investigations and criminal prosecutions.[70] According to whistleblower lawyer Mark Zaid, excluding contractors was "a remarkable and obviously intentional oversight, given the significant number of contractors who now work within the intelligence community. This is a gap that desperately needs to be closed, as I often have contractors coming to me with whistleblower-type concerns and they are the least protected of them all."[72] National security contractors used to have stronger whistleblower rights under the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 (NDAA), which protected Department of Defense contractors against reprisal. The law also created a process through which contractors could request a remedy, initially through agency Inspector General investigations and subsequently through access to district court jury trials for civil complaints. The law covered close to 60 percent of government contractors, including NSA, DIA and other intelligence community whistleblowers working at the Pentagon, but it didn't cover CIA contractors. These rights were subsequently removed through the 2013 NDAA (passed prior to Edward Snowden's disclosures) and no longer apply. As a result, according to PEN America, since 2013 intelligence community contractors (such as Edward Snowden) "have had significantly fewer (and weaker) protections than other government contractors, and no statutory protection against retaliation (with the exception of security clearance-related reprisals, from which they are protected from under PPD-19)."[70] Some whistleblower advocates believe that the framework created by PPD-19 is insufficient and that intelligence community whistleblowers will have effective, meaningful rights only if they are given access to courts to challenge retaliation.[70] The 2014 Intelligence Authorization Act, which was signed into law on July 7, 2014, codifies some protections from PPD-19.[70]

Reporting

To qualify for an award under the Security and Exchange Commission's Whistleblower Program, information regarding possible securities law violations must be submitted to the Commission in one of the following ways:

- Online through the Commission's Tip, Complaint or Referral Portal; or.

- By mailing or faxing a Form TCR to: SEC Office of the Whistleblower.

First, when submitting a tip, it is important to use the Form TCR, which is required to be considered a whistleblower for this program. It contains declarations of eligibility that one must sign off on. A tip can be submitted anonymously, but if this is the case, one must be represented by counsel. When a whistleblower tip is submitted, a TCR submission number will be given in return. When a TCR is submitted to the SEC, their attorneys, accountants, and analysts will review the data submitted to determine how best to proceed.

If it is a matter the Enforcement Division is working on already, the TCR gets forwarded to the staff handling that matter. Often a TCR gets sent to the experts in another Division at the SEC for their evaluation. Even if the tip does not cause an investigation to be opened right away, the information provided is retained and may be reviewed again in the future if more facts come to light. If the tip submitted does cause an SEC investigation, the enforcement staff will follow the facts to determine whether to charge an individual, entity, or both with securities violations. These investigations can take months, or even years to be concluded.

If a matter in which over one million dollars in sanction is ordered is final, a Notice of Covered Action will be posted on the SEC website. The Whistleblower then has 90 days to submit a Form WB-APP to apply for an award. From there, deeper analysis is required by the Commission's rules to determine whether to pay an award, and, if so, how much. The Commission's rules describe seven factors used to determine whether to increase or decrease the percentage of an award.

The four factors that may increase an award are:

- the significance of the information provided by the whistleblower

- the assistance provided by the whistleblower

- any law enforcement interest that might be advanced by a higher award

- the whistleblower's participation in internal compliance systems - as in, if you reported on a company that you currently or used to work for, did you report internally first, and did you participate in any internal investigation

There are also three factors that can decrease the percentage of an award. They are as follows:

- culpability

- an unreasonable reporting delay by the whistleblower

- interference with internal compliance and reporting systems

The best thing to do in order to make the tip useful is to provide specific, timely, and credible information. The staff will be able to pursue an investigation of the tip if they have specific examples, details, or transactions to examine. So, the more information and specifics provided, the better. Any updates or developments that occur along the way should also be sent in. It is also helpful to understand that the Commission considers both positive and negative factors when determining an award percentage.

Lastly, it is important to note that the securities laws can be very complex and that SEC enforcement actions can take years to be finalized once reported.[73]

Federal workers

Federal workers notify the Secretary of Labor[74] when unsafe working conditions are not addressed by management. Senior executives and military officers at the rank colonel, captain, or above have an obligation to act on whistleblower information. Financial or business irregularities may be reported to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Attorney General, District Attorney, Secret Service, Federal Bureau of Investigation, or other law-enforcement agency.

If the reported information is classified, then the recipient should have a need to know and must hold a security clearance. The need-to-know criteria generally mean that the issue being disclosed will benefit the government if the dispute is resolved. A dispute that does not provide a benefit to the government is more appropriate for a labor dispute.

Federal employment is governed by the Merit Promotion Protection Board.[36] This applies to positions that are not filled by election or appointment. Federal employees are covered by the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which offers inferior protection.

Workers who report crime or incompetence may get injured while at work. Federal workers, energy workers, longshoremen, and coal workers injured at work should contact the US Department of Labor, Office of Workers Compensation.[75]

Private companies and non-profit organizations

Employees working for private companies notify organizations like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Even though EPA and OSHA may provide no direct services for government workers, a report should be filed.

Government ethics laws are a complicated maze with unpredictable combinations. As an example, any business interests and tax records for a public employee is public domain because disclosure is required by the Ethics Reform Act of 1989 (Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 101–194) and this information should be made available to anyone who requests that information because of the Freedom of Information Act. This applies to all government employees, including elected and political appointments. Employees working for private companies are also protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Private companies and non-profit organizations benefit when whistleblower protection is included in company policies and bylaws. Fines, penalties, and lawsuits may be avoided when immunity from prosecution is granted to any employee who notifies an owner or member of the board of directors when other employees or managers become involved in unethical or illegal activity on behalf of the organization.

Workers must assert their rights to obtain any kind of protection.

Unionization

Unions may provide additional legal protection that may be unavailable without unionization.

The National Labor Review Board (NLRB)[76] helps to form federal unions, investigate charges, seek resolutions, decide cases, and enforce orders.[77] The NLRB oversees the formation of the union, petitions, and election process associated with selecting union officials.

Employers are obligated to inform employees about assistance programs associated with workplace injuries or illness, and union representatives are obligated to follow up on this information. Employers are required to allow the local union representative to attend meetings. The employer cannot interfere with support provided by the union representative.

A collective bargaining agreement (a contract) is a set of bylaws that establishes a partnership agreement between two groups of people, where one group is management and the other group is employees. The collective bargaining agreement also provides the same protection for managers, except managers are not entitled to union representation during labor disputes.

The collective bargaining agreement is separate from the union charter, which is the set of rules and regulations governing the activities of the labor union members.

- Voting and elections

- Union meetings

- Meeting notification

- Funds

Labor contracts involve Common Law established by court decisions (except in Louisiana), torts (private or civil law), and public law.

A union may be organized as a business or corporate entity under U.S. Code Title 26, Section 501(c)(3), 501(c)(4) and/or 501(c)(5)[78] if the labor organization is large enough to conduct banking transactions. A bank, credit union, savings and loan, or other financial organization can be consulted to determine the local requirements needed to establish an account. This allows funds to be collected for a common purpose.

Labor disputes

Labor disputes typically refer to controversy between an employer and its employees regarding the terms (such as conditions of employment, fringe benefits, hours of work, tenure, wages) to be negotiated during collective bargaining, or the implementation of already agreed upon terms.

One caution related to a labor dispute is that all union leadership team members are also employees, and these employees have job assignments. Lighter job assignments are usually given union leaders. In addition to not requiring the union leadership team members to be in the workplace during work hours, this can often include fewer travel assignments. Management has the right to change the job assignment for union leaders. This includes family separation using long-term travel assignments.

The whistleblower must understand the labor dispute process because union leadership may be corrupt.

The employee should initiate a labor dispute to protect their employment rights when reprisal occurs after a whistleblower disclosure. Employee rights are protected by labor law in the United States. These rights are not automatically guaranteed if the employee fails to start the process in a timely manner.

Employees with no collective bargaining organization are directly represented by state labor boards,[79] unemployment offices,[80] and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.[81] This describes employees where no union steward is available at the work-site.

The dispute must be disclosed to the employer. If there is a union contract, then the process described in the contract should be followed. If there is no union agreement, then a disagreement with the employer should be discussed directly with government organizations that provide employee protection for the area of the disagreement. A labor dispute that progresses beyond words begins with a grievance.

Grievances

A grievance is an official complaint by an employee about an employer's actions believed to be wrong or unfair.

The grievance starts a timer that usually prohibits the employer from taking negative action against the employee (and union steward). For example, a whistleblower complaint prohibits negative employer action for 90 to 180 days. A conventional grievance should provide a 30-day window. This prohibits things like workplace lockout, withholding payroll and firing. Each new employer action can be used to justify a new grievance.

When an employee grievance prevails, the lower-level supervisors who were involved in the dispute may be temporarily prohibited from promotion. Manager pay may be suspended in situations where there was a whistleblower reprisal or other crime. This provides a manager incentive to not use unethical tactics. The employee should ensure that the nature of the dispute is factual, justified, and substantiated. Factual means no false or misleading statements. Justified means there must be legal justification to sway a judge or jury to favor the employee. Substantiated means there must be evidence, testimonials, and witnesses to support the facts stated.

A grievance should include the following:

- Organization information (name and location)

- Employee contact information (name, address, and telephone)

- Manager contact information (name, address, and telephone)

- Employee occupation

- Nature of complaint

- Desired resolution

- Employee signature and date

- Manager reply, signature, and date

The original grievance is given to the first-level manager, and a copy is kept for the immediate supervisor. If there is a union, then a copy should be given to a member of the union leadership team. If the manager reply is unacceptable, then the grievance is updated, attached to copies of the original, and given to the manager who supervises of the first-level manager (second-level supervisor). This continues from manager to manager upward through the organization. The time allowed for each manager response is usually 30 days. The time allowed for the employee response is usually seven days. The nature of the complaint may expand to include further information at each step.

When an employee dispute involves an employer that is a member of a collective-bargaining unit, then the grievance process is described in the collective-bargaining agreement. U.S. Code Title 5 Section 7121[82] for federal workers provides an example framework.

If no resolution is achieved at the top level for the local organization, or if the process takes too long, then the process is brought to the attention of the appropriate, government organization.

Collective bargaining protects the employer as much as the employee. The grievance process described above provides time for the employer to correct situations that violate ethical rules or laws before enforcement action becomes necessary. Federal employees who are members of a union are generally restricted to binding arbitration. Employees not limited to binding arbitration may sue in court.

If there is no labor union, if the union dispute process has produced no productive results, or if the process takes too long, then the issue is submitted to the National Labor Review Board,[83] Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,[81] the Merit Promotion Protection Board,[36] the Inspector General, Senator,[84] Representative,[85] the President,[86] the Department of Justice,[87] the Industrial Accidents Board,[88] or other organization. A copy should be mailed to the officer or senior executive in charge of the top-level managers in the local organization because other employees may interfere with regular delivery.

A grievance needs to cite an issue involving tort law, common law, or public law to be effective. There is no obligation for any enforcement action for issues that do not violate law.

Some common reasons for employee complaints are as follows:

- Failure to provide pay for hours worked

- Criminal activity

- Dangerous activity

- Assault

- Failure to provide time for meals/breaks

- Failure to provide safe working conditions

- Hostile work environment (i. e. harassment)

- Failure to accommodate handicap are most common reasons for employee complaints.

Meetings

The direct supervisor may order an employee to attend a meeting. The employee must attend a meeting during regular working hours, but there are limitations. U.S. government employees cannot leave the meeting or work area, except in situations involving disability or illness. Government leave policy is established by public law.[89] Employees working for private companies operate under different rules, and if state laws require time for employee breaks and meals, restricting employee movement could be an arrest in some areas. Due to unequal protection, government employees are at greater risk of serious abuse by managers.

The state labor board should be consulted for more information.[79]

One word of caution is that Fifth Amendment protection may be lost if the employee answers questions, and it is necessary to reassert this right during the meeting after answering any questions. The meeting may involve very little conversation after the employee has asserted their constitutional rights and demanded the details of the accusation.

The employee must also assert their rights. Department of Labor should be consulted for more information.[90]

Employees must assert additional rights when ordered to attend a meeting that may involve any type of dispute. There is nothing that requires an employee to provide any information during a meeting if the topic involves a labor dispute, but the employee is entitled to be told the specific nature of any possible dispute.

The following should be demanded:

- Job description

- Performance evaluation criteria

- Performance evaluation

- Improvement expectations

Employees must never make false statements during any meeting, and meeting participants risk fine or prison when false statements are made when a federal worker is present. False statements[91] made in the presence of a federal employee are a crime, and this includes any statement made during an official meeting at a federal facility. Some states may have similar laws.

A court order may be required for telephone voice recording in some areas. Ordinary voice recording in some areas, such as California, requires consent of all parties before the recording can be used in a courtroom or during arbitration. Most meeting minutes are documented in writing by all parties, and the minutes are signed and dated at the end of the meeting.

The employees should request the specific nature of any accusation under the Sixth Amendment with the assumption that an unresolved dispute will be decided in a courtroom under the protections provided by the Seventh Amendment. Employees cannot be compelled to answer questions about potential crimes under the assumption that all such questions fall under the protection of the Fifth Amendment. No employee may be denied these protections for any reason.

The specific constitutional protections are as follows:

Fourteenth: ... nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws ...

If the meeting is a disciplinary hearing or a performance appraisal meeting for a government employee, and if the employee is told that any area of job performance is less-than-perfect, then the employee is entitled to be told about specific improvements for each less-than-perfect rating. The appraisal must fall within the boundaries of the job description. If any area of the appraisal falls outside the scope of any diploma, license, or prior training used during the hiring process, then the employer is responsible for training necessary to improve the skills that are part of the evaluation. The employer is required to allow an improvement period before reevaluation. Some employers may require employees to pay for their own training in some areas as a hiring condition.

Another protection is false imprisonment. The employer cannot lock doors and cannot forcibly move the employee against their will, unless an arrest has been performed, including a Miranda warning. The Sixth amendment requires that the employee must be told about the reason when moved against their will or detained against their will.

Rules vary by state, but employees are usually entitled to a 15-minute paid break every two hours and an unpaid meal hour after every four. In most states, employees are entitled to overtime for any missed break periods, and state labor protection rules extend to federal workers.

One of the benefits of union representation is Weingarten rights[92] to reduce employer abuse. Employees not represented by a union may have limited Weingartern rights, and may not be entitled to witnesses during a meeting. The employee and the union representative have the right to management information related to the dispute and both the employee and the union representative may take an active role during any meetings.

Weingarten rights are as follows:

- Employee has the right to union representation during discussion requested by management

- Employee must ask a manager if the discussion may involve disciplinary action

- Employee must ask the union steward to attend the discussion

- Employee must inform employer that union representation has been requested

- If employer refuses union representation:

- State "If this discussion could in any way result in my being disciplined or terminated then I respectfully request union representation. I choose to not respond to questions or statements without union representation."

- Take notes, do not answer questions, do not sign documents, and inform union after discussion

- Employee has the right to speak privately with union representation before the discussion and during the discussion

- The union representative is an active participant. He or she is not just a passive witness.

Government employees also have Garrity rights to assert Fifth Amendment protection related to employment that is completely different from Miranda rights that apply to employees working for private companies.

One issue with public employees is that certain workplace situations violate public law. Government employees who deviate from office procedures may violate laws, such as the New Jersey ticket fixing scandal[93] and the Minnesota ticket fixing scandal.[94] Employees who carry pesticide into the workplace from home violate the Hazard Communication Standard.[95]

Managers may threaten to take disciplinary employment action if an employee fails to disclose criminal activity. Government employees also have Garrity rights, and must assert the following when questioned by management. This must be separate from any report or statement from management if made in writing.

- "On ____________— (date) _________— (time), at ____________— (place) I was ordered by _________________— (superior officer, name & rank) to submit this report (statement) as a condition of continued employment. In view of possible job forfeiture, I have no alternative, but to abide by this order and to submit this compelled report (statement).

- It is my belief and understanding that this report (statement) will not and cannot be used against me by any governmental agency or related entity in any subsequent proceedings, other than disciplinary proceedings within the confines of the department itself.

- For any and all other purposes, I hereby assert my constitutional right to remain silent under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and any other rights prescribed by (state) laws. Further, I rely specifically upon the protection afforded me under the doctrines set forth in Garrity v New Jersey, 385 US 493 (1967), Gardner v Broderick, 392 US 273 (1968), and their progeny, should this report (statement) be used for any other purpose of whatsoever kind or description."

- The employer shall not order or otherwise compel a public employee, under threat of discipline, to waive the immunity of the asserted Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination with respect to any submitted statement or report or answers to questions. (Employees shall not condition their compliance with a lawful order to submit reports, statements, etc. on non-disclosure to third parties by the employer.)

- Propriety of the discipline shall be determined through the collective bargaining agreement grievance arbitration process.

Exemptions and limitations to whistleblower protections

There are certain limitations and exemptions to the legal protections for whistleblowers in the U.S. With regard to federal legislation, the broadest law is the Whistleblower Protection Act. However, its protections apply only to federal employees. Both public and private employees may be protected under topic-specific federal laws, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Act, but such laws cover only a narrow, specific area of unlawful activity. Private sector employees are not protected by federal whistleblower protection statutes if they report either violations of federal laws with no whistleblower protection provisions or violations of state laws, although they may have some protection under local laws.[96] In 2009, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report stating that employees who reported illegal activities did not receive enough protection from retaliation by their employers. Based on data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, only 21% of the 1800 whistleblower cases reviewed by the agency in 2007 had "a favorable outcome" for the whistleblower. The GAO found that the key issues were lack of resources for investigating employees' claims and the legal complexity of whistleblower protection regulations.[97]

In the United States, union officials are exempted from whistleblower laws. There are currently no legal protections for employees of labor unions who report union corruption, and such employees can be dismissed from employment should they raise any allegations of financial impropriety.[98] The Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, which legislates against union corruption, includes protections for whistleblowers, however the Supreme Court has ruled that these protections apply only to union members and not to employees of labor unions.[99]

References

- 5 U.S.C. 2302(b)(8)-(9), Pub.L. 101-12 as amended.

- Jennings, Julie; Nagel, Jared C. (January 12, 2018). "Federal Workforce Statistics Sources: OPM and OMB (Table 3. Total Federal Employment)" (PDF). fas.org. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- "USOGE | Executive Order 12674 (Apr. 12, 1989): Principles of Ethical Conduct for Government Officers and Employees". Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- "USOGE | Standards of Ethical Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch".

- "EO 12356 - NATIONAL SECURITY INFORMATION". fas.org. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "SECNAV INSTRUCTION 5370.7C" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- "U.S.C. Title 10 - ARMED FORCES". www.govinfo.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "DoDD 7050.06" (PDF). Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Whistleblower Ombudsman | Office of Inspector General | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services". oig.hhs.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Home | Office of Inspector General". www.oig.dhs.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "United States Air Force Inspector General > Home". www.afinspectorgeneral.af.mil. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Official Website for the Office of the Inspector General | Department of the Army Inspector General, | The United States Army". www.daig.pentagon.mil. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Hotline". www.dodig.mil.

- "Inspector General of the Marine Corps > Units". www.hqmc.marines.mil. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Service (USMS), U. S. Marshals. "U.S. Marshals Service". www.usmarshals.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Official Website of the Office of the Commander, Naval Surface Forces Office of the Inspector General". www.public.navy.mil. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "2010 California Code, Penal Code, Article 2. Reports Of Injuries". Justia US Law Library.

- See, e.g. Fisher v Carrousel Motor Hotel, Inc., 424 S.W.2d 627 (1967).

- See, e.g., Leichtman v. WLW Jacor Communications, 92 Ohio App.3d 232 (1994) (cause of action for battery where tortfeasor blew cigarette smoke in another's face).

- "2010 Florida Code, TITLE XLVI CRIMES, Chapter 784 ASSAULT; BATTERY; CULPABLE NEGLIGENCE 784.03 Battery; felony battery". Justia US Law Library.

- "Funding Advisor: Appropriations". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- "California Labor Code Section 6425 - California Attorney Resources - California Laws". law.onecle.com. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- N.Y. Labor Law § 740.

- See N.Y. Social Services L. § 413.

- Vilarin v. Rabbi Haskel Lookstein School, 96 A.D. 1 (1st Dep't 2012).

- Leonard M. Rosenberg, "In New York Courts", NYSBA Health Journal, 6, Summer/Fall 2012 (Vol. 17, No. 3).

- US EPA, OAR (July 3, 2014). "Indoor Air Quality (IAQ)". US EPA. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Lahman, Larry D. "Bad Mules: A Primer on the Federal False Claims Act", 76 Okla. B. J. 901, 901 (2005)". www.okbar.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- Curry, William Sims (2010). Government Contracting: Promises and Perils. CRC Press. pp. 205. ISBN 9781420085662.

- Rose-Ackerman, Susan (1999). Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58. ISBN 9780521659123.

- Government, United States (2011). "The False Claims Act: A Primer" (PDF). Justice.gov: 1–28. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- .com, Encyclopedia. "Lloyd-La Follette Act". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "Freedom of Information Act: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Department of Justice, United States. "What is FOIA?". FOIA.gov. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Government, United States. "Civil Service Reform Act of 1978". Archives - Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board". www.mspb.gov.

- "U.S. Office of Personnel Management - www.OPM.gov". U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "FLRA | U.S. Federal Labor Relations Authority". www.flra.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "B-139503, JUNE 1, 1959, 38 COMP. GEN. 815". U.S. Government Accountability Office. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- "U.S. Department of Defense". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "News". www.afmc.af.mil.

- "ASP - U.S. Army Suggestion Program". Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- "Marine Corps Incentive Program" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- "Unknown" (PDF).

- "Inside DOD". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Types of Retirement". U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Types of Retirement". U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Campbell, Alan K. (1978). "Civil Service Reform: A New Commitment". Public Administration Review. 38 (2): 99–103. doi:10.2307/976281. JSTOR 976281.

- "U.S. Office of Government Ethics". Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- Publishing Office, U.S. Government (2010). "Ethics in Government Act of 1978" (PDF). United States Code Supplement 4, Title 5 - Government Organization and Employees: 57–86. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "U.S. Senate: 404 Error Page". www.senate.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Committee on Standards of Official Conduct". Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- "United States Courts". United States Courts. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Home". osc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Prohibited Personnel Practices". Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- "Whistleblower Disclosures". Archived from the original on November 29, 2006. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- Law School, Cornell University. "Ethics in Government Act of 1978". Legal Information Institute. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "Public Law 101-12, 1989" (PDF). Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- [Robert J. McCarthy, "Blowing in the Wind: Answers for Federal Whistleblowers," 3 WILLIAM & MARY POLICY REVIEW 184 (2012)]

- Mizutani, Hideo (2007). "Whistleblower Protection Act" (PDF). Japan Labor Review: 1–25. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Shimabukuro, Jon O.; Whitaker, L. Paige (2012). "Whistleblower Protections Under Federal Law: An Overview" (PDF). Congressional Research Service (1–22). Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Devine, Thomas M. (1999). "The Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989: Foundation for the Modern Law of Employment Dissent". Administrative Law Review. 51 (2): 531–579. JSTOR 40709996.

- Government, United States. "The Whistleblower Protection Programs". United States Department of Labor: Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "United States Whistleblowers: Labor Law, Whistleblowers, United States". USLegal Law Digest. USLegal Inc. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Government, United States. "No FEAR Act Notice". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Romano, Roberta (2004). "The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the Making of Quack Corporate Governance". Yale Law School, NBER, and ECGI: 1–12. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "SEC.gov | The Laws That Govern the Securities Industry". www.sec.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "NAAG | NAAG". www.naag.org. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Associates, Addison-Hewitt. "The Sarbanes-Oxley Act". A Guide To The Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- "Secret Sources: Whistleblowers, National Security and Free Expression" (PDF). PEN America. November 10, 2015. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- "Presidential Policy Directive 19" (PDF). October 10, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- Davidson, Joe (August 12, 2013). "Obama's 'misleading' comment on whistleblower protections". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- Securities and Exchange Commission, U.S. "What Happens to Tips". SEC: Office of the Whistleblower. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "U.S. Department of Labor -- Office of the Secretary of Labor Hilda L. Solis". Archived from the original on December 17, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- "Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP) - U.S. Department of Labor". www.dol.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Who We Are | National Labor Relations Board". www.nlrb.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- "What We Do | National Labor Relations Board". www.nlrb.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- "26 U.S. Code § 501 - Exemption from tax on corporations, certain trusts, etc". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "State Labor Offices | U.S. Department of Labor". www.dol.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "CareerOneStop". www.careeronestop.org. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Federal EEO Complaint Processing Procedures | U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission". www.eeoc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "5 U.S. Code § 7121 - Grievance procedures". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "NLRB :: National Labor Relations Board". Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- "U.S. Senate: Senators of the 116th Congress". www.senate.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Write Your Representative - Contact your Congressperson in the U.S. House of Representatives". Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- "Contact the White House". The White House. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Contact the Department". www.justice.gov. September 16, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "All 50 States' and D.C.'s Home Pages and Workers' Compensation Agencies". Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- "Federal Employees and Bone Marrow or Organ Donor Leave". U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "U.S. Department of Labor -- OSDBU -- Poster Page". Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- Linnea B. McCord, J. D.; Kim Greenhalgh, J. D.; Michael Magasin, J. D. (2004). "Businesspersons Beware: Lying is a Crime". Graziadio Business Review. 7 (3). Retrieved July 23, 2020 – via gbr.pepperdine.edu.

- "University of Hawai'i - West O'ahu Center for Labor Education & Research". Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- "Law.com". Law.com. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "TMCEC :: Ticket Fixing". Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- "Guidance for Hazard Determination for Compliance with the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Sinzdak, Gerard (2008). "An Analysis of Current Whistleblower Laws: Defending a More Flexible Approach to Reporting Requirements". California Law Review. 96 (6): 1633–1669. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- "GAO: Nation's Whistleblower Laws Inadequately Enforced, Needs Additional Resources". democrats.edworkforce.house.gov. Committee on Education and the Workforce. February 26, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Tremoglie, Michael P. (June 4, 2012). "Group urges OSHA to protect union whistleblowers". Legal Newsline. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Sherk, James (May 23, 2012). "Extend Whistle-Blower Protections to Union Employees". heritage.org. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

External links

Policy:

- Employment law: Department of Labor

- Environmental law: Environmental Protection Agency

- Occupational health & safety law: Department of Labor Archived November 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Indoor air quality: Environmental Protection Agency

- Restricted use products: Environmental Protection Agency

- Worker protection standard: Environmental Protection Agency

- Hazard communication: Environmental Protection Agency

- GSA: facilities standards for the public buildings service (federal building code)

Laws:

- United States Code, Title 9: Arbitration (union workers)

- United States Code, Title 29: Labor (all workers)

- United States Code, Title 5: Government Organization and Employees (government workers)

- United States Code, Title 40: Public Buildings, Properties, and Works

Regulations: