White Ship

The White Ship (French: la Blanche-Nef; Medieval Latin: Candida navis) was a vessel transporting many nobles, including the heir to the English throne, that sank in the Channel during a trip from France to England near the Normandy coast off Barfleur, on 25 November 1120.[1] Only one of approximately 300 people aboard, a butcher from Rouen, survived.[2]

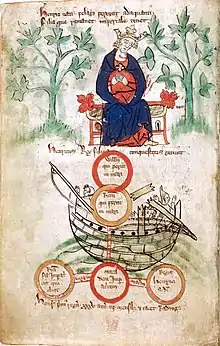

The White Ship sinking | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Blanche-Nef |

| Out of service | 25 November 1120 |

| Fate | Struck a submerged rock off Barfleur, Normandy |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Sailing ship |

| Installed power | Square sails |

| Propulsion | Wind and oars |

Those who drowned included William Adelin, the only legitimate son and heir of Henry I of England, his half-siblings Matilda of Perche and Richard of Lincoln, the earl of Chester Richard d'Avranches, and Geoffrey Ridel. With William Adelin dead, the king had no obvious successor, and his own death 15 years later set off a succession crisis and a period of civil war in England known as the Anarchy (1135–1153).

Shipwreck

The White Ship was a newly refitted vessel captained by Thomas FitzStephen (Thomas filz Estienne), whose father Stephen FitzAirard (Estienne filz Airard) had been captain of the ship Mora for William the Conqueror during the Norman conquest of England in 1066.[3] Thomas offered his ship to Henry I of England to return to England from Barfleur in Normandy.[4] Henry had already made other arrangements, but allowed many in his retinue to take the White Ship, including his heir, William Adelin, his illegitimate children Richard of Lincoln and Marie FitzRoy, Countess of Perche, and many other nobles.[4]

According to chronicler Orderic Vitalis, the crew asked William Adelin for wine and he supplied it to them in great abundance.[4] By the time the ship was ready to leave there were about 300 people on board, although some, including the future king Stephen of Blois, had disembarked due to the excessive drinking before the ship sailed.[5]

The ship's captain, Thomas FitzStephen, was ordered by the revellers to overtake the king's ship, which had already sailed.[5] The White Ship was fast, of the best construction and had recently been fitted with new materials, which made the captain and crew confident they could reach England first. However, when it set forth in the dark, its port side struck a submerged rock called Quillebœuf, and the ship quickly capsized.[5]

William Adelin got into a small boat and could have escaped but turned back to try to rescue his half-sister, Matilda, when he heard her cries for help. His boat was swamped by others trying to save themselves, and William drowned along with them.[5] According to Orderic Vitalis, Berold (Beroldus or Berout), a butcher from Rouen, was the sole survivor of the shipwreck by clinging to the rock. The chronicler further wrote that when Thomas FitzStephen came to the surface after the sinking and learned that William Adelin had not survived, he let himself drown rather than face the king.[6]

One legend holds that the ship was doomed because priests were not allowed to board it and bless it with holy water in the customary manner.[7][lower-alpha 1] For a complete list of those who did or did not travel on the White Ship, see Victims of the White Ship disaster.

Repercussions

A direct result of William Adelin's death was the period known as the Anarchy. The White Ship disaster had left Henry I with only one legitimate child, a second daughter named Matilda. Although Henry I had forced his barons to swear an oath to support Matilda as his heir on several occasions, a woman had never ruled in England in her own right. Matilda was also unpopular because she was married to Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, a traditional enemy of England's Norman nobles. Upon Henry's death in 1135, the English barons were reluctant to accept Matilda as queen regnant.

One of Henry I's male relatives, Stephen of Blois, the king's nephew by his sister Adela, usurped Matilda as well as his older brothers William and Theobald to become king. Stephen had allegedly planned to travel on the White Ship but had disembarked just before it sailed;[4] Orderic Vitalis attributes this to a sudden bout of diarrhea.

After Henry I's death, Matilda and her husband Geoffrey of Anjou, the founder of the Plantagenet dynasty, launched a long and devastating war against Stephen and his allies for control of the English throne. The Anarchy lasted from 1138 to 1153 with devastating effect, especially in southern England.

Contemporary historian William of Malmesbury wrote:

No ship that ever sailed brought England such disaster, none was so well known the wide world over. There perished then with William the king's other son Richard, born to him before his accession by a woman of the country, a high-spirited youth, whose devotion had earned his father's love; Richard earl of Chester and his brother Othuel, the guardian and tutor of the king's son; the king's daughter the countess of Perche, and his niece, Theobald's sister, the countess of Chester; besides all the choicest knights and chaplains of the court, and the nobles' sons who were candidates for knighthood, for they had hastened from all sides to join him, as I have said, expecting no small gain in reputation if they could show the king's son some sport or do him some service.[8]

Historical fiction

- Reference to the sinking of the White Ship is made in Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth (1989) and its later game adaptation. The ship's sinking sets the stage for the entire background of the story, which is based on the subsequent civil war between Matilda (referred to as Maud in the novel) and Stephen. In Follett's novel, it is implied that the ship may have been sabotaged; this implication is seen in the TV adaptation – even going so far as to show William Adelin assassinated whilst on a lifeboat – and the video game adaptation.

- Ellen Jones, The Fatal Crown (1991)

- Sharon Kay Penman describes the sinking in detail in her historical novel When Christ and His Saints Slept (1994).

- The sinking of the White Ship is briefly referenced in Glenn Cooper's novel The Tenth Chamber (2010).

- The White Ship sets the stage for the 2009 novel Hiobs Brüder (The Brothers of Job) by the German author Rebecca Gablé, which details the rise of Henry II of England, son of Empress Matilda.

- The long conflict between Stephen and Matilda is important in the Brother Cadfael series. This 20-book set of mysteries, by Ellis Peters, has a 12th-century Benedictine monk as its protagonist. Depending on the book, the conflict is either very important or serves as a backdrop to the plots. The sinking directly affects the outcome of the short story "A Light on the Road to Woodstock".

Poetry

- Felicia Hemans, "He Never Smiled Again", c. 1830[9]

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "The White Ship: a ballad"; first published 1881 in his collected Ballads and Sonnets.[10]

- Edwin Arlington Robinson, "Ballad of a Ship", 1891[11]

- Geoffrey Hill, "The White Ship". In his first book, For the Unfallen, 1959.

- Franck K. Lehodey, "White Ship". A graphic novel, 2011.

Notes

- Guillaume de Nangis wrote that the White Ship sank because all the men aboard were sodomites. See: ’’Chron.’’ in Rolls series, ed. W. Stubbs (London, 1879), vol. 2, under A.D. 1120. This reflects the medieval belief that sin caused pestilence and disaster. See also: Codex Justinian, nov. 141. Another theory is expounded by Victoria Chandler, "The Wreck of the White Ship", in The final argument: the imprint of violence on society in medieval and early modern Europe, edited by Donald J. Kagay and L.J. Andrew Villalon (1998). Her theory discusses the possibility of it being a mass murder.

References

- Spencer, Charles Spencer, Earl (2020). The White Ship: conquest, anarchy and the wrecking of Henry I's dream. London. ISBN 9780008296827.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - There are seven accounts of the disaster: Orderic Vitalis, Historia ecclesiastica 12.26 (ed. and trans. Chibnall, 1978, pp. 294–307); William of Malmesbury, Gesta regum Anglorum 5.419 (ed. and trans. Mynors, Thomson, and Winterbottom, 1998, pp. 758–763); Simeon of Durham, Historia regum 100.199 (ed. T. Arnold, 1885, vol. 2, pp. 258–259); Eadmer, Historia nouorum in Anglia (ed. M. Rule, 1884, pp. 288–289), Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum 7.32 (ed. and trans. Greenway, 1996, pp. 466–467), Hugh the Chanter, History of the Church at York (ed. and trans. Johnson, 1990, pp. 164–165), Robert of Torigni, Gesta Normannorum ducum (ed. and trans. E. van Houts, 1995, vol. 2, pp. 216–219, 246–251, 274–277), and Wace, Roman de Rou, pt. iii, lines 10173–10262 (ed. A. Holden, 1973, vol. 2, pp. 262–266).

- Elisabeth M.C, van Houts, 'The Ship List of William the Conqueror', Anglo-Norman Studies X: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1987, ed. R. Allen Brown (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1988), pp. 172–173

- Judith A. Green, Henry I: King of England and Duke of Normandy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 165

- William M. Aird, Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy c. 1050–1134 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2008), p. 269

- The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis. Vol. 6. Marjorie Chibnall (ed. and trans.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1978. pp. 298–299. ISBN 978-0-19-822243-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Jones, Dan (2014). The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England. Penguin Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0143124924.

- Gesta regum Anglorum/The history of the English kings. R.A.B. Mynors, Rodney M. Thomson, Michael Winterbottom (eds. and trans.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1998. pp. 761–763. ISBN 0-19-820678-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "The Poetical Works of Mrs. Hemans : electronic version". University of California, British Women Romantic Poets Project. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- "Dante Gabriel Rossetti: "The White Ship: a ballad"". Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- "Edwin Arlington Robinson – Ballad of a Ship". Americanpoems.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.