Whitechapel Mount

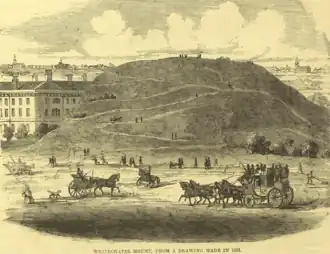

Whitechapel Mount was a large artificial mound of disputed origin. A prominent landmark in 18th century London, it stood in the Whitechapel Road beside the newly constructed London Hospital, being not only older, but significantly taller. It was crossed by tracks, served as a scenic viewing-point (and a hiding place for stolen goods), could be ascended by horses and carts, and supported some trees and formal dwelling-houses. It has been interpreted as: a defensive fortification in the English Civil War; a burial place for victims of the Great Plague; rubble from the Great Fire of London; and as a laystall (hence it was sometimes called Whitechapel Dunghill). Possibly all of these theories are true to some extent.

Whitechapel Mount was physically removed around 1807. Because Londoners widely believed in the "Great Fire rubble" theory, the remains were sifted by antique hunters, and some sensational finds were claimed. It survives in its present-day placename Mount Terrace, E1.

Location

Neighbourhood

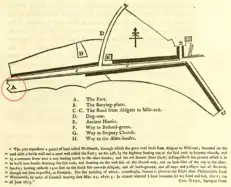

Whitechapel Mount was on the south side of the Whitechapel Road, on the ancient route from the City of London to Mile End, Stratford, Colchester and Harwich. In the 18th century and later the surroundings were mostly fields: grazing for cows or market gardens.[2]

Leaving London, a traveller would pass the church of St Mary Matfelon (origin of the name "white chapel") on the right, then a windmill, before arriving at the Mount. Across the Whitechapel Road was a burying ground and the Ducking Pond. Further east, at the turnpike, the name changed to Mile End Road, with Dog Row (today Cambridge Heath Road) branching off to Bethnal Green.

According to John Strype (1720) the neighbourhood was a busy one, with good inns for travellers in Whitechapel[3] and good houses for sea captains in Mile End.[4] Even so, said Strype, the Whitechapel Road was "pestered" by illegally built, poor quality dwellings.[5]

Another source said it was infested by highwaymen, footpads and riff-raff of all kinds who preyed on travellers to and from London.[6] News and court reports speak of murders and robberies. In two Old Bailey cases stolen property was buried in, and recovered from, Whitechapel Mount.[7][8] It was a place of resort for pugilists and dog-fighters.[9]

From the summit of Whitechapel Mount an extensive view of the hamlets of Limehouse, Shadwell, and Ratcliff could be obtained.[10]

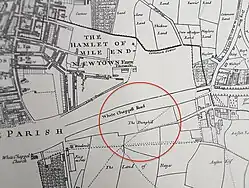

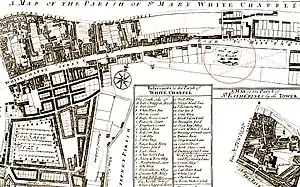

On maps

Whitechapel Mount's position is first depicted in a 1673 building plan by Sir Christopher Wren, where he refers to it as "the mud wall called the Fort".[11] In Joel Gascoyne's survey of the parish of Stepney (1703) it is called The Dunghill: it is at least 400 yards long, and is crossed not only by a path, but a road.

In John Rocque's map of London (1746) it has been horizontally truncated, but is shown with substantial elevation, with at least one dwelling-house – if not a terrace of houses – on its western end. In Richard Blome's map of 1755 it has a large dwelling-house with front drive and appears alongside the newly built London Hospital. In John Cary's 1795 map its western portion has been truncated by the newly built New Road, but appears to have a substantial building in its northwest corner.

Possible origins

Civil War fortification

.png.webp)

In 1643 London was hastily fortified against the Royalist armies, for "there is terrible news that [Prince] Rupert will sack it and so a complete and sufficient dike and earthern wall and bulwarks must be made".[12]

Twenty-three or 24 earthen forts were built at intervals around the city and its main suburbs; neighbouring forts were in sight of one another. These forts were manned by volunteers e.g. men too old to be in the regular militia; local innkeepers were ordered to provide them with food.[13]

The forts were interconnected by an earth bank and trench, dug by "great numbers of men, women and young children".[14] All social classes[15] joined in the labour:

From ladies down to oyster-wenches

Labour'd like pioneers in trenches,

Fell to their pick-axes and tools,

And help'd the men to dig like moles.[16]

The completed ring was 18 miles in circumference. A visiting Scotsman walked it; it took him 12 hours.[17]

Fort No.2, officially a hornwork with two flanks, commanded the Whitechapel Road.[18] The Scottish traveller, who inspected it, said it was a "nine angled fort only pallosaded and single ditched and planted with seven pieces of brazen ordnance [brass cannon], and a court du guard [guardhouse] composed of timber and thatched with tyle stone as all the rest are".[19] There was a trench around its base.[20]

Daniel Lysons said the earthwork at Whitechapel was[21] 329 foot long, 182 foot broad and more than 25 foot above ground level.[22]

After the civil war these fortifications were swiftly removed because they spoiled productive agricultural land. However traces remained and one of these was Whitechapel Mount.[23] Wrote Lysons (1811): "The east end was till of late years very perfect; on the west side some houses had been built. The surface on the top, except where it had been dug away, was perfectly level.[22] Mount Street, Mayfair, is another relict name of one of these civil war forts.[24]

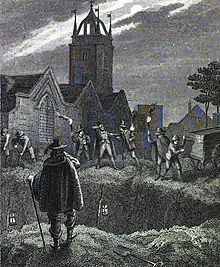

Great Plague burial ground

In the bubonic epidemic of 1665 an estimated 70,000-100,000 Londoners died of the plague. Aldgate, Whitechapel and Stepney were badly affected. This placed a strain on the burial facilities and some were buried in mass graves.[25]

Official mass graves were made by opening a deep pit and leaving it open for as long as it took to fill with cadavers, which was done downwind. The number of lost plague pits in London is commonly exaggerated — most mass graves were actually in pre-existing churchyards . However there were some gaps in the records and "undoubtedly some temporary and irregular plague burial sites".[26] Those willing to man the dead carts (and dispose of the corpses) were not fastidious; a contemporary said they were ‘very idle base liveing men and very rude", drawing attention to their task by swearing and cursing.[27]

No contemporaneous record confirms corpses were officially buried in Whitechapel Mount. It is known that there were several burial grounds or plague pits in the vicinity[28] e.g. across the road.[29][30] Whether the mound was used as a burial ground has been disputed.[10] According to popular tradition, it was. In one version, Whitechapel Mount's origin was that rubble from the Fire of London was thrown over a plague pit to cover it up.[31][10] These rumours were denied by the authorities when they proposed to remove Whitechapel Mount; they had it "pierced" in an effort to refute them. [32][33]

The clearest reputable source is the author Joseph Moser, who wrote

In the course of last summer [1802], when part of the rubbish of [Whitechapel Mount] had just been removed, I had the curiosity to inspect the place, and observed in the different strata a great number of human bones, together with those, apparently, of different animals, oxen, or cows, and sheep’s horns, bricks, tiles, &c. The bones and other exuvia of animals were in many places, especially towards the bottom, bedded in a stiff, viscid earth, of the blueish colour and consistence of potter's clay, which was unquestionably the original ground, thrown into different directions, as different interments operated upon its surface.[31]

A complication is that the London Hospital itself may have used the Mount for burials: a hospital history says that by 1764 "The Mount Burying Ground was full".[34]

Great Fire detritus

The Great Fire of London occurred the year after the plague. The nearest burnt environment was a mile away. Even so, respectable sources asserted that Whitechapel Mount was formed or augmented from rubble from the Fire of London,[35] including Dr Markham the rector of Whitechapel Church, who took pains to investigate the subject.[36] This origin theory was widely believed,[20][10][37][38] though some denied it.[39][20] When the Mount was dismantled in the 19th century the belief attracted flocks of antique hunters; see below.

Laystall

The above theories about the origin of Whitechapel Mount, by themselves, may not account for its sheer size as shown in the maps and illustrations cited.

A laystall was an open rubbish tip; towns relied on them for disposing of garbage, and did so until the sanitary landfills of the 20th century. By legislation of October 1671 seven laystalls were appointed for the City of London. All street sweepings and household rubbish was to be collected in carts and had to be tipped in one of these, and nowhere else. One of them was Whitechapel Mount: it was to receive the rubbish from the wards of Portsoken, Tower, Duke's Place and Lime Street.[40]

However, a laystall was more than a passive tip: it was a business. Its proprietor employed gangs of men, women and boys to sort the rubbish and recycle it.[41][42] Without him, nothing prevented indiscriminate fly-tipping and random lateral spread onto adjoining properties. William Guy who investigated the laystalls of mid-19th century London reported

In most of the laystalls or dustmen's yards, every species of refuse matter is collected and deposited:– nightsoil, the decomposing refuse of markets, the sweepings of narrow streets and courts, the sour-smelling grains from breweries, the surface soil of the leading thoroughfares, and the ashes from the houses. The proportion in which these several matters are collected, vary... In all these establishments the bulk of the deposits consists of dust from the houses, which is sifted on the spot by women and boys seated on the dust-heaps, assisted by men who are engaged in filling the sieves, sorting the heterogeneous materials, or removing and carting them away.[43]

While the legislation speaks of "dung, soil, filth and dirt", most domestic refuse (by volume) comprised household dust[44] typically coal ash – hence the expression "dustman" – and this could be used for making bricks.[45] At the close of the 18th century there was a tremendous demand for bricks to build the rapidly expanding London; "At night, a 'ring of fire' and pungent smoke encircled the City"; there were numerous local brickfields e.g. at Mile End.[46] An Old Bailey case of 1809 records that bricks were being delivered from the diminishing Whitechapel Mount.[47]

Removal

The construction of the East and West India Docks early in the nineteenth century caused roads to be made through the low marshy fields extending from Shadwell and Ratcliff to Whitechapel. New Street/Cannon Street Road, leading from Whitechapel Mount to St George in the East so increased the value of the land on each side of it, that the Corporation of London decided to take down the Mount. This occurred in 1807–8, and Mount Place, Mount Terrace, and Mount Street were then built on that site, thus marking the spot where the Mount stood.[10]

The process took several years, efforts at first being desultory.[48] There was even a proposal – a prefiguring of the Regent's Canal – to bring a canal from Paddington to the docks at Wapping by passing through Whitechapel Mount.[49]

The soil of the Mount was used to make bricks, see above, and these were delivered to e.g. Wentworth Street, Bethnal Green and "Hanbury's Brewhouse"[47] (the Black Eagle Brewery), buildings that stand today.

Antique hunters

Believing it to contain detritus from the Fire of London, flocks of cockney enthusiasts examined the Mount's soil.[50] Various antiques were found in it – or alleged to be found in it, since it gave them provenance[38] – including a silver tankard[37] and a Roman coin.[51]

The most spectacular find was a carved boar's head with silver tusks; it was, said reputable antiquarians, an authentic memento of the Boar's Head Inn, Eastcheap: a setting for Shakespeare plays, Falstaff, Mistress Quickly and so forth, and genuinely burnt down in the Fire of London.[52][9]

Archaeology

For lack of access, there has been no systematic archaeological investigation of the site. However, redevelopment of the Royal London Hospital has allowed occasional glimpses.

Mackinder (1994), London Hospital Medical College, Newark Building, Grid Reference TQ3456815:

Evaluation produced evidence of a deep cut feature on the alignment of the English Civil War defences. A subsequent excavation found the feature to be a ditch, 5.5m wide and 1.4m deep, filled with waterlain silts (the earliest dating to the 17th century), which was backfilled in the late 18th century. Other activity consisted of an undated drainage channel. Later, there were two post holes possibly forming a fence-line and possibly associated with a rutted gravel surface that post-dated the infilling of the ditch. A large quantity of post-medieval red ware sugar cone moulds and collecting jars were recovered from the infilling of the ditch and later levelling of the site.[53]

Aitken (2005), The Front Green, Royal London Hospital, Grid Reference TQ347816:

Post-medieval deposits, ashy fill deposits were recorded below the cellars of former terrace houses facing Whitechapel Road. Extensive fill deposits may indicate quarrying, which took place after a successful petition to flatten the Mount fort by the hospital authorities at the end of the 18th century. There is no trace of a former burial ground on the site prior to that date and no disturbed graves or disarticulated human bone was recovered. A rise in the ground level to a metre above that of the surrounding Whitechapel and New Roads indicates a topographic replacement of the Mount as an elevated feature and the same rise is reflected along the 19th century Mount Terrace. No significant archaeological deposits were observed.[54][55]

In theatre, literature and popular song

The Skeleton Witness: or, The Murder at the Mound by William Leman Rede was a play performed on the English and American stage. The villain does a murder and conceals the body in Whitechapel Mount. The crime is done in such a way that, should the remains be discovered, the impoverished hero will get the blame, though innocent. The hero goes abroad for seven years and makes his fortune. On his return to London, about to marry the heroine, he learns, to his horror, that the Mount is to be cleared away, digging to start on the morrow. To stop this, he hurries off to the Mount's owner and buys it at an extravagant price. The vendor, suspicious, wonders if the Mount contains a buried treasure and sends some men to poke around. They discover the skeleton. By a complicated plot twist the hero proves his innocence and gets the girl, both living happily ever after.[56]

The Mount was used as a metonymy to denote the east end or extremity of London town, as in "from the farthest extent of Whitechapel mount to the utmost limits of St Giles",[57] or "[the news] was all over town, from Hyde Park Corner to Whitechapel dunghill".[58] The Coachman, a popular 18th century song,[59] began

I'm a boy full spunk, and my name's little Joe,

It's I that can tip the long trot;

From Whitechapel-mount up to fam'd Rotten-row,

With the ladies sometimes is my lot.

References and notes

- So claimed in the Illustrated London News, 26 April 1860. However the drawing seems to have been made from memory: St Anne's Limehouse (top left) is back to front.

- Bull 1956, pp. 25, 28–9: and see Milne's map itself.

- Strype 1720, II.2.27: "Whitechapel is a spacious fair Street for Entrance into the City Eastward, and somewhat long, reckoning from the Laystall [N.B.] East unto the Bars West, where the Ward [of Portsoken] ends. It is a great Thorough fair, being the Essex Road, and well resorted unto, which occasions it to be the better inhabited, and accommodated with good Inns for the Reception of Travellers, and for Horses, Coaches, Carts and Waggons".

- Watson 1995, p. 245: "Mile-end Town stands here; built with many good Houses, inhabited with divers Sea Captains and Commanders of Ships: Two East India Captains ... and other Persons of good Quality."

- Strype 1720, IV.2.44: "[B]oth the sides of the Street be pestered with Cottages and Allies, even up to Whitechapel Church; and almost half a Mile beyond it, into the Common Field; all which ought to lie open and free for all Men. But this common Field (I say) being sometime the Beauty of this City on that Part, is so incroached upon, by building of filthy Cottages, and with other purpresters, Inclosures, and Lay Stalls, that (notwithstanding all Proclamations and Acts of Parliament made to the contrary) in some Places it scarce remaineth a sufficient Highway for the meeting of Carriages and Droves of Cattel: much less is there any fair, pleasant, or wholesome Way, for People to walk on Foot: which is no small Blemish to so famous a City, to have so unsavory and unseemly an Entry or Passage thereunto."

- Morris 1910, p. 77.

- R v. Travis 1734.

- R v. Patrick 1747.

- Norman 1897, p. 54.

- Clunn 1937, p. 255.

- Lysons 1811, p. 694.

- Brett-James 1928, p. 9.

- Brett-James 1928, p. 30.

- Brett-James 1928, pp. 5–13.

- Brett-James 1928, pp. 4, 10, 12, 16.

- Samuel Butler, Hudibras, cited Brett-James, op. cit,, 4.

- Brett-James 1928, p. 14.

- Brett-James 1928, p. 6: "A hornworke with two flankers be placed at Whitechappell windmills." (Resolution of the Common Council of February 1643.)

- Brett-James 1928, p. 17.

- Emerson 1862, p. 183.

- Presumably, when built. Lysons uses the past tense to refer to the fortification itself, not its later accretions; later maps and images show the remains (with accretions) were much larger.

- Lysons 1811, p. 714.

- Brett-James 1928, pp. 23, 25, 28–32.

- Brett-James 1928, p. 35.

- Porter 2012, 1134, 1143.

- Harding 1993, pp. 55, 59, 64.

- Porter 2012, 968.

- Holmes 1896, p. 127.

- Birch 1881, pp. 515–8.

- Maps of Wren (1673), Rocque (1746) and Blome (1774).

- Moser 1803, p. 415.

- Malcolm 1807, p. 353.

- Wallis 1810, p. 356.

- Morris 1910, p. 292.

- Lambert 1806, p. 86.

- Moser 1803, p. 414.

- Domestic Events 1805, p. 65.

- Juninus 1813, p. 127.

- Lysons 1811, p. 714n.

- Entick 1766, pp. 287–297.

- Guy 1848, pp. 73–4.

- Mayhew 1861, p. 172.

- Guy 1848, pp. 723–4: Dr Guy reported that the laystall workers were significantly more healthy than his control group.

- Guy 1848, p. 72.

- Mayhew 1861, p. 170.

- Bull 1956, p. 28.

- R v. Hall 1809.

- Proposals for purchasing and carying away the soil were invited in 1801: Morning Chronicle, 23 March 1801, p.1. Joseph Moser examined the strata in 1802:Moser 1803, p. 415 Work must have ceased, for The Monthly Mirror of July 1806 reported "The removal of Whitechapel Mount has commenced":Domestic Events 1805, p. 65 Bricks were still being delivered from Whitechapel Mount in 1809: R v. Hall 1809

- Morning Post, 21 January 1803, p.3.

- The Times, 30 July 1805, p.2.

- Hobler 1860, p. 327.

- Timbs 1855, p. 265.

- Mackinder 1994.

- MOLAS 2004.

- Aitken 2005, p. 17.

- Rede 1868.

- The Scots Magazine 1739, p. 611.

- Roberts 1836, p. 96.

- Crosby 1799, p. 68.

Sources

- Aitken, R. (2005). "The Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Road, London, E1: An Archaeological Evaluation Report" (PDF). MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology). doi:10.5284/1026414. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Birch, George H. (1881). "Stray Notes on the Church and Parish of S. Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel". Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. J. H. & J. Parker. 5: 516–519. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Brett-James, Norman G. (1928). "The Fortification of London in 1642/3". London Topographical Record. London Topographical Society. 14: 1–35. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Bull, G. B. G. (1956). "Thomas Milne's Land Utilization Map of the London Area in 1800". The Geographical Journal. The Royal Geographical Society. 122 (1): 25–30. JSTOR 1791472.

- Clunn, Harold P. (1937). The Face of London: The Record of a Century's Changes and Development. New York; London: E.P. Dutton; Simpkin Marshall. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Cooke, G. A. (1832). Walks Through London; or, a Picture of the British Metropolis. London: Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Crosby, B. (1799). Modern Songster. London: Crosby. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Domestic Events". The Monthly Mirror: Reflecting Men and Manners. Vol. 20. London: Vernon and Hood. July 1805. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- Emerson, George Rose (1862). London: How the Great City Grew. London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Entick, John (1766). A New and Accurate Survey of London, Westminster, Southwark and Places Adjacent. Vol. 2. Edward and Charles Dilly. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Flintham, David (1999). "Whitechapel Mount and the London Hospital". THHOL. Mernick. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Guy, William Augustus (1848). "On the Health of Nightmen, Scavengers, and Dustmen". Journal of the Statistical Society of London. Wiley. 11 (1): 72–81. JSTOR 2337767.

- Harding, Vanessa (1993). "Burial of the plague dead in early modern London" (PDF). In Champion, J. A. I. (ed.). Epidemic Disease in London. Centre for Metropolitan History. pp. 53–64. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Hobler, Francis (1860). Roman History from Cnæus Pompeius to Tiberius Constantinus as Exhibited on the Roman Coins Collected by Francis Hobler. Vol. 1. Westminster: John Bowyer Nichols and Sons. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Holmes, Mrs Basil (Isabella M.) (1896). The London Burial Grounds. Notes on their History from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. New York: Macmillan. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Juninus (1813). "Conversations on the Arts". Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashion and Politics. Vol. 9, no. 51. R. Ackermann. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Lambert, R. (1806). The History and Survey of London and its Environs from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Vol. 4. London: T. Hughes, M. Jones. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Lysons, Daniel (1811). The Environs of London: Being An Historical Account of the Towns, Villages and Hamlets Within Twelve Miles of the Capital. Vol. 2(2) (2nd ed.). London: Cadell and Davies. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Mackinder, A. (1994). "London Hospital Medical College, Newark Building, New Road, London E1, London Borough of Tower Hamlets". MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Malcolm, James Pelham (1807). Londinium Redivivum, or an Ancient History and Modern Description of London. Vol. 4. London: Longman Rees Hurst & Orme. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Mayhew, Henry (1861). London Labour and the London Poor: Cyclopædia of the Conditions and Earnings of Those that Will Work, Those that Cannot Work, and Those that Will Not Work. Vol. 2. London: Griffin, Bohn. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- MOLAS (2004). "The Front Garden, Royal London Hospital, Whitechape Road, E1: an archaeological watching brief report". Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Morris, E. W. (1910). A History of the London Hospital. London: Edward Arnold. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Moser, Joseph (1803). "Vestiges, Collected and Recollected". The European Magazine and Monthly Review. Vol. 43. Philological Society of London. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Norman, Philip (1897). London Signs and Inscriptions. Elliot Stock. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Porter, Stephen (2012). The Great Plague (Kindle ed.). Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-1219-5.

- R v. Hall (1809). The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- R v. Patrick (1747). The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- R v. Travis (1734). The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Rede, William Leman (1868). The Skeleton Witness: or, The Murder at the Mound. A Domestic Drama in Three Act, as Performed at the Principal English and American Theatres. New York: Samuel French. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Roberts, William (1836). Memories of the Life of Mrs Hannah More. Vol. 1. London: Senley and Burnside. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Strype (1720). A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (online ed.). ISBN 0-9542608-9-9. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London. London: David Bogue. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "To my Esteem'd Fellow-labourers". The Scots Magazine. 22 December 1739.

- Wallis, John (1810). London: being a Complete Guide to the British Capital (3rd ed.). Sherwood, Neeley and Jones. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Watson, Isobel (1995). "From West Heath to Stepney Green: building development in Mile End Old Town, 1660–1820". London Topographical Record. London Topographical Society. 27: 231–256. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Whitechapel Mount". The Times. London. 30 July 1805.

External links

- Mount Terrace in the Survey of London

_showing_the_location_of_Whitechapel_Mount.png.webp)