The Dark Knight

The Dark Knight is a 2008 superhero film directed by Christopher Nolan from a screenplay co-written with his brother Jonathan. Based on the DC Comics superhero Batman, it is the sequel to Batman Begins (2005) and the second installment in The Dark Knight Trilogy. The plot follows the vigilante Batman, police lieutenant James Gordon, and district attorney Harvey Dent, who form an alliance to dismantle organized crime in Gotham City. Their efforts are derailed by the Joker, an anarchistic mastermind who seeks to test how far the Batman will go to save the city from chaos. The ensemble cast includes Christian Bale, Michael Caine, Heath Ledger, Gary Oldman, Aaron Eckhart, Maggie Gyllenhaal, and Morgan Freeman.

| The Dark Knight | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Christopher Nolan |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | Characters appearing in comic books published by DC Comics |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Wally Pfister |

| Edited by | Lee Smith |

| Music by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 152 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $185 million |

| Box office | $1.006 billion[lower-alpha 3] |

Warner Bros. Pictures prioritized a sequel following the successful reinvention of the Batman film series with Batman Begins. Christopher and Batman Begins co-writer David S. Goyer developed the story elements, making Dent the central protagonist caught up in the battle between the Batman and the Joker. In writing the screenplay, the Nolans were influenced by 1980s Batman comics and crime drama films, and sought to continue Batman Begins' heightened sense of realism. From April to November 2007, filming took place with a $185 million budget in Chicago and Hong Kong, and on sets in England. The Dark Knight was the first major motion picture to be filmed with high-resolution IMAX cameras. Christopher avoided using computer-generated imagery unless necessary, insisting on practical stunts such as flipping an 18-wheel truck and blowing up a factory.

The Dark Knight was marketed with an innovative interactive viral campaign that initially focused on countering criticism of Ledger's casting by those who believed he was a poor choice to portray the Joker. Ledger died from an accidental prescription drug overdose in January 2008, leading to widespread interest from the press and public regarding his performance. When it was released in July, The Dark Knight received acclaim for its mature tone and themes, visual style, and performances—particularly that of Ledger, who received many posthumous awards including Academy, BAFTA, and Golden Globe awards for Best Supporting Actor, making The Dark Knight the first comic-book film to receive major industry awards. It broke several box-office records and became the highest-grossing 2008 film, the fourth-highest-grossing film of its time, and the highest-grossing superhero film.

Since its release, The Dark Knight has been assessed as one of the greatest superhero films ever made, one of the best movies of the 2000s, and one of the best films ever made. It is considered the "blueprint" for many modern superhero films, particularly for its rejection of a typical comic-book movie style in favor of a crime film that features comic-book characters. Many filmmakers sought to repeat its success by emulating its gritty, realistic tone to varying degrees of success. The Dark Knight has been analyzed for its themes of terrorism and the limitations of morality and ethics. The United States Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2020. A sequel, The Dark Knight Rises, concluded The Dark Knight trilogy in 2012.

Plot

A gang of clown-themed masked criminals robs a mafia-owned bank in Gotham City, betraying and killing each other until the sole survivor, the Joker, reveals himself as the mastermind and escapes with the money. The vigilante Batman, district attorney Harvey Dent, and police lieutenant Jim Gordon ally to eliminate Gotham's organized crime. The Batman's true identity, the billionaire Bruce Wayne, publicly supports Dent as Gotham's legitimate protector, as Wayne believes Dent's success will allow the Batman to retire, allowing him to romantically pursue his childhood friend Rachel Dawes, despite her relationship with Dent.

Gotham's mafia bosses gather to discuss protecting their organizations from the Joker, the police, and the Batman. The Joker interrupts the meeting and offers to kill the Batman for half of the fortune their accountant, Lau, concealed before fleeing to Hong Kong to avoid extradition. With the help of Wayne Enterprises CEO Lucius Fox, the Batman finds Lau in Hong Kong and returns him to the custody of Gotham police. His testimony enables Dent to apprehend the crime families. The bosses accept the Joker's offer, and he kills high-profile targets involved in the trial, including the judge and police commissioner. Although Gordon saves the mayor, the Joker threatens that his attacks will continue until the Batman reveals his identity. He targets Dent at a fundraising dinner and throws Rachel out of a window, but Batman rescues her.

Wayne struggles to understand the Joker's motives, but his butler Alfred Pennyworth says "some men just want to watch the world burn." Dent claims he is the Batman to lure out the Joker, who attacks the police convoy transporting him. The Batman and Gordon apprehend the Joker, and Gordon is promoted to commissioner. At the police station, the Batman interrogates the Joker, who says he finds the Batman entertaining and has no intention of killing him. Having deduced the Batman's feelings for Rachel, the Joker reveals she and Dent are being held separately in buildings rigged to explode. The Batman races to save Rachel while Gordon and the other officers go after Dent, but they discover the Joker gave their positions in reverse. Rachel is killed in the explosion, while Dent's face is severely burned on one side. The Joker escapes custody, extracts the fortune's location from Lau, and burns all of it, killing Lau in the process.

Wayne Enterprises accountant Coleman Reese deduces the Batman's identity and attempts to expose it, but the Joker threatens to blow up a hospital unless Reese is killed. While the police evacuate hospitals and Gordon struggles to keep Reese alive, the Joker meets with a disillusioned Dent, persuading him to take the law into his own hands and avenge Rachel. Dent defers his decision-making to his half-scarred, two-headed coin, killing the corrupt officers and the mafia involved in Rachel's death. As panic grips the city, the Joker reveals two evacuation ferries, one carrying civilians and the other prisoners, are rigged to explode at midnight unless one group sacrifices the other. To the Joker's disbelief, the passengers refuse to kill one another. The Batman subdues the Joker but refuses to kill him. Before the police arrest the Joker, he says although the Batman proved incorruptible, his plan to corrupt Dent has succeeded.

Dent takes Gordon's family hostage, blaming his negligence for Rachel's death. He flips his coin to decide their fates, but the Batman tackles him to save Gordon's son, and Dent falls to his death. Believing Dent is the hero the city needs and the truth of his corruption will harm Gotham, the Batman takes the blame for his death and actions and persuades Gordon to conceal the truth. Pennyworth burns an undelivered message to Wayne from Rachel, who said she chose Dent, and Fox destroys the invasive surveillance network that helped the Batman find the Joker. The city mourns Dent as a hero, and the police launch a manhunt for the Batman.

Cast

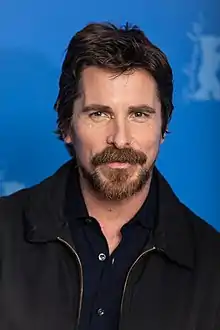

- Christian Bale as Bruce Wayne / Batman: A wealthy socialite who as a child was traumatized by his parents' murder. Wayne secretly operates as the heroic vigilante Batman.[4]

- Michael Caine as Alfred Pennyworth: Wayne's father-figure, trusted butler, and confidant[5][6]

- Heath Ledger as the Joker: A criminal mastermind and anarchist who is determined to sow chaos and corruption throughout Gotham[4][7][8]

- Gary Oldman as James Gordon: One of the few honest officers in the Gotham City Police Department (GCPD) who assists the Batman's war on crime[7][9]

- Aaron Eckhart as Harvey Dent / Two-Face: Gotham's noble district attorney-turned-violent vigilante[7][10][11]

- Maggie Gyllenhaal as Rachel Dawes: Gotham's assistant district attorney and Wayne's childhood friend, who is divided between her feelings for him and for Dent.[12]

- Morgan Freeman as Lucius Fox: Wayne Enterprises' CEO who supplies technology and equipment for the Batman's campaign[13][14][15]

Additionally, Eric Roberts, Michael Jai White, and Ritchie Coster appear as crime bosses Sal Maroni, Gambol, and the Chechen, respectively; while Chin Han portrays Lau, a Chinese criminal banker.[lower-alpha 4] The GCPD cast includes Colin McFarlane as commissioner Gillian B. Loeb, Keith Szarabajka and Ron Dean as detectives Stephens and Wuertz, Monique Gabriela Curnen as rookie detective Anna Ramirez[2][21][22] and Philip Bulcock as Murphy.[2]

The cast also features Joshua Harto as Wayne Enterprises employee Coleman Reese,[23] Anthony Michael Hall as news reporter Mike Engel,[24][25] Néstor Carbonell as mayor Anthony Garcia, William Fichtner as a bank manager, Nydia Rodriguez Terracina as Judge Surrillo,[2] Tom "Tiny" Lister Jr. as a prisoner, Beatrice Rosen as Wayne's Russian ballerina date, and David Dastmalchian as the Joker's paranoid schizophrenic henchman Thomas Schiff.[2][25][26] Melinda McGraw, Nathan Gamble, and Hannah Gunn portray Gordon's wife Barbara, his son James Jr., and his daughter, respectively.[2][27] The Dark Knight features several cameo appearances from Cillian Murphy, who reprises his role as Jonathan Crane / Scarecrow from Batman Begins;[28][29] musical performer Matt Skiba;[30] as well as United States Senator and life-long Batman fan Patrick Leahy, who has appeared in or voiced characters in other Batman media.[31]

Production

Development

Following the critical and financial success of Batman Begins (2005), the film studio Warner Bros. Pictures prioritized a sequel.[32] Although Batman Begins ends with a scene in which Batman is presented with a joker playing card, teasing the introduction of his archenemy, the Joker, Christopher Nolan did not intend to make a sequel and was unsure Batman Begins would be successful enough to warrant one.[33][34] Christopher, alongside his wife and longtime producer Emma Thomas, had never worked on a sequel film[35] but he and co-writer David Goyer discussed ideas for a sequel during filming. Goyer developed an outline for two sequels, but Christopher remained unsure how to continue the Batman Begins narrative while keeping it consistent and relevant, though he was interested in utilizing the Joker in Begins's grounded, realistic style.[32][34][35] Discussions between Warner Bros. Pictures and Christopher began shortly after Batman Begins's theatrical release, and development began following the production of Christopher's The Prestige (2006).[32]

Writing

Goyer and Christopher collaborated for three months to develop The Dark Knight's core plot points.[35] They wanted to explore the theme of escalation and the idea that the Batman's extraordinary efforts to combat common crimes would lead to an opposing escalation by criminals, attracting the Joker, who uses terrorism as a weapon. The joker playing card scene in Batman Begins was intended to convey the fallacy of the Batman's belief his war on crime would be temporary.[34][36] Goyer and Christopher did not intentionally include real-world parallels to terrorism, the war on terror, and laws enacted to combat terrorists by the United States government because they believed making overtly political statements would detract from the story. They wanted it to resonate with and reflect contemporary audiences.[35] Christopher described The Dark Knight as representative of his own "fear of anarchy" and Joker represents "somebody who wants to just tear down the world around him."[37]

Although he was a fan of Batman (1989), starring Jack Nicholson as the Joker, Goyer did not consider Nicholson's portrayal scary and wanted The Dark Knight's Joker to be an unknowable, already-formed character, similar to the shark in Jaws (1975), without a "cliché" origin story.[lower-alpha 5] Christopher and Goyer did not give their Joker an origin story or a narrative arc, believing it made the character scarier; Christopher described their film as the "rise of the Joker". They felt the threat of cinematic villains such as Hannibal Lecter and Darth Vader had been undermined by subsequent films depicting their origins.[lower-alpha 6]

With Christopher's help, his brother Jonathan spent six months developing the story into a draft screenplay. After submitting the draft to Warner Bros., Jonathan spent a further two months refining it until Christopher had finished directing The Prestige. The pair collaborated on the final script over the next six months during pre-production for The Dark Knight.[35][41] Jonathan found the "poignant" ending the script's most interesting aspect; it had always depicted the Batman fleeing from police but was changed from him leaping across rooftops to escaping on the Batpod, his motorcycle-like vehicle. The dialogue Jonathan considered most important, "you either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain", came late in development.[41] Influenced by films such as The Godfather (1972) and Heat (1995), and maintaining Batman Begins's tone, their finished script bore more resemblance to a crime drama than a traditional superhero film.[lower-alpha 7]

Comic-book influences included writer Frank Miller's 1980s works, which portray characters in a serious tone, and the limited series Batman: The Long Halloween (1996–1997), which explores the relationship between the Batman, Dent, and Gordon.[38][43] Dent was written as The Dark Knight's central character, serving as the center of the battle between the Batman, who believes Dent is the hero the city needs, and the Joker, who wants to prove even the most righteous people can be corrupted. Christopher said the title refers to Dent as much as the Batman.[lower-alpha 8] He considered Dent as having a duality similar to the Batman's, providing interesting dramatic potential.[10]

Focusing on Dent meant Bruce Wayne / Batman was written as a generally static character who did not undergo drastic character development.[35][44][45] Christopher found writing the Joker the easiest aspect of the script. The Nolans identified the traits common to his media incarnations and were influenced by the character's comic-book appearances as well as the villain Dr. Mabuse from the films of Fritz Lang.[34][39] Writer Alan Moore's graphic novel, Batman: The Killing Joke (1988), did not influence the main narrative but Christopher believed his interpretation of the Joker as someone partially driven to prove anyone can become like him when pushed far enough helped the Nolans give purpose to an "inherently purposeless" character.[34][35][39] The Joker was written as a purely evil psychopath and anarchist who lacks reason, logic, and fear, and could test the moral and ethical limits of the Batman, Dent, and Gordon.[lower-alpha 9] Christopher and Jonathan later realized they had inadvertently written their version similarly to Joker's first appearance in Batman #1 (1940).[lower-alpha 10] The final scene, in which the Joker states he and the Batman are destined to battle forever, was not intended to tease a sequel but to convey the diametrically opposed pair were in an endless conflict because they will not kill each other.[47]

Casting

.jpg.webp)

Describing how his character had evolved from Batman Begins, Christian Bale said Wayne had changed from a young, naive, and angry man seeking purpose to a hero who is burdened by the realization his war against crime is seemingly endless.[48][49][50] Because the new Batsuit allowed him to be more agile, Bale did not increase his muscle mass as much as he had for Batman Begins. Christopher had deliberately obscured combat in the previous film because it was intended to portray the Batman from the criminals' point of view. The improved Batsuit design let him show more of Bale's Keysi-fighting method training.[51]

Christopher was aware Nicholson's popular portrayal of the Joker would invite comparisons to his version, and wanted an actor who could cope with the associated scrutiny.[lower-alpha 11] Ledger's casting in August 2006 was criticized by some industry professionals and members of the public who considered him inappropriate for the role; executive producer Charles Roven said Ledger was the only person seriously considered, and that Batman Begins's positive reception would help alleviate any concerns.[lower-alpha 12] Christopher was confident in the casting because discussions between himself and Ledger had demonstrated they shared similar ideas regarding the Joker's portrayal.[34][52] Ledger said he had some trepidation in succeeding Nicholson in the role but that the challenge excited him.[34][55] He described his interpretation as a "psychopathic, mass-murdering, schizophrenic clown with zero empathy", and avoided humanizing him. He was influenced by Alex from the crime film A Clockwork Orange (1971), and British musicians Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious.[lower-alpha 13]

Ledger spent about a month secluding himself in a hotel room while reading relevant comic books. He developed the character's voice by mixing a high-pitch and low-pitch, which was inspired by ventriloquist performances. His fighting style was designed to appear improvised and erratic.[lower-alpha 14] Ledger spent a further four months creating a "Joker diary" containing images and elements he believed would resonate with his character, such as finding the disease AIDS humorous.[59] Describing his performance, Ledger said: "It's the most fun I've had with a character and probably will ever have ... It was an exhausting process. At the end of the day, I couldn't move. I couldn't talk. I was absolutely wrecked."[57] In a November 2007 interview, Ledger said when committing himself to any role, he had difficulty sleeping because he could not relax his mind, and often slept only two hours a night during filming.[59]

Christopher wanted to cast an actor with an all-American "heroic presence" for Harvey Dent, something he likened to Robert Redford but with an undercurrent of anger or darkness.[52] Josh Lucas, Ryan Phillippe, and Mark Ruffalo were considered, as well as Matt Damon, who could not commit due to scheduling conflicts.[lower-alpha 15] According to Christopher, Eckhart had the all-American charm and "aura ... of a good man pushed too far".[10][52] Eckhart found portraying conflicted characters to be interesting; he said the difference between Dent and the Batman is the distance they are willing to go for their causes, and that after Dent's corruption he remains a crime fighter but he takes this to an extreme because he dislikes the restrictions of the law.[10][66] Eckhart's performance was influenced by the Kennedy family, particularly Robert F. Kennedy, who fought organized crime with a similarly idealistic view of the law.[67] During discussions on the portrayal of Dent's transformation into Two-Face, Eckhart and Christopher agreed to ignore Tommy Lee Jones's "colorful" portrayal in Batman Forever (1995), in which the character has pink hair and wears a split designer suit, in favor of a more realistic, slightly burnt, neutral-toned suit.[67]

Describing his role as GCPD sergeant James Gordon, Oldman said Gordon is the "moral center" of The Dark Knight, an honest and incorruptible character struggling with the limits of his morality.[68][69] Maggie Gyllenhaal replaced Katie Holmes as Rachel Dawes, as Holmes chose to star in the crime comedy Mad Money (2008) instead.[70][71] Gyllenhaal approached Rachel as a new character and did not reference Holmes's previous performance. Christopher described Rachel as the emotional connection between Wayne and Dent, ultimately serving as a further personal loss to fuel Wayne's character. Gyllenhaal collaborated with Christopher on the character's depiction because she wanted Rachel to be important and meaningful in her relatively minor role.[lower-alpha 16] Musician Dwight Yoakam turned down a role as the bank manager or a corrupt police officer because he was recording his album Dwight Sings Buck (2007).[74]

Pre-production

In October 2006, location scouting for Gotham City took place in the UK in Liverpool, Glasgow, London, and parts of Yorkshire, and in several cities in the U.S.[75][76] Christopher chose Chicago because he liked the area and believed it offered interesting architectural features without being as recognizable as locations in better-known cities such as New York City.[35][77] Chicagoan authorities had been supportive during filming of Batman Begins, allowing the production to shut stretches of roads, freeways, and bridges.[78] Christopher wanted to exchange the more natural, scenic settings of Batman Begins such as the Himalayas and caverns for a modern, structured environment the Joker could disassemble. Production designer Nathan Crowley said the clean, neat lines of Chicagoan architecture enhanced the urban-crime drama they wanted to make, and that the Batman had helped improve the city. The destruction of Wayne Manor in Batman Begins provided an opportunity to move Wayne to a modern, sparse penthouse, reflecting his loneliness.[79] Sets were still used for some interiors such as the Bat Bunker, the replacement for the Batcave, on the outskirts of the city. The production team considered placing it in the penthouse basement but believed it was too unrealistic a solution.[80]

Much of The Dark Knight was filmed using Panavision's Panaflex Millennium XL and Platinum cameras but Christopher wanted to film about 40 minutes with IMAX cameras, a high-resolution technology using 70 mm film rather than the more-commonly used format 35 mm; the finished film includes 15–20% IMAX footage, running for about 28 minutes.[lower-alpha 17] This made it the first major motion picture to use IMAX technology, which was generally employed for documentaries.[lower-alpha 18] Warner Bros. was reluctant to endorse the use of the technology because the cameras were large and unwieldy, and purchasing and processing the film stock cost up to four times as much as typical 35 mm film. Christopher said cameras that could be used on Mount Everest could be used for The Dark Knight, and had cinematographer Wally Pfister and his crew begin training to use the equipment in January 2007 to test its feasibility.[86][87][88] Christopher particularly wanted to film the bank heist prologue in IMAX to immediately convey the difference in scope between The Dark Knight and Batman Begins.[89]

Filming in Chicago

Principal photography began on April 18, 2007, in Chicago on a $185 million budget.[lower-alpha 19][lower-alpha 20] For The Dark Knight, Pfister chose to combine the "rust-style" visuals of Batman Begins with the "dusk"-like color scheme of The Prestige (cobalt blues, greens, blacks, and whites), in part to address over-dark scenes in Batman Begins.[81][94] To avoid attention, filming in Chicago took place under the working title Rory's First Kiss but the production's true nature was quickly uncovered by media publications.[95] The Joker's homemade videos were filmed and mainly directed by Ledger. Caine said he forgot his lines during a scene involving one video because of Ledger's "stunning" performance.[34]

The first scene filmed was the bank heist, which was shot in the Old Chicago Main Post Office over five days.[81][96] It was scheduled early to test the IMAX procedure, allowing it to be refilmed with traditional cameras if needed, and it was intended to be publicly released as part of the marketing campaign.[97] Pfister described it as a week of patience and learning because of the four-day wait for the IMAX footage to be processed.[89] Filming moved to England throughout May, returning to Chicago in June.[81][98]

Filming took place in the lobby of One Illinois Center, which served as Wayne's penthouse apartment; bookcases were built to hide the elevators. A floor of Two Illinois Center was decorated for Wayne's fundraiser. The crew was described as excited as this scene depicted the first meeting between the Batman and the Joker. The windows in both settings were covered in green screen material, allowing Gotham City visuals to be added later.[81][99] In July, three weeks were spent filming the truck chase scene, mainly on Wacker Drive, a multi-level street that had to be closed overnight.[100][101] During filming, Christopher added a set-piece of a SWAT van crashing through a concrete barricade.[102] The sequence continued on LaSalle Street, which was also used for the GCPD funeral procession, for a practical truck-flip stunt and helicopter sequence.[103] Additional segments were filmed on Monroe Street and Randolph Street, and at Randolph Street Station.[101][104][105]

Navy Pier, along the shore of Lake Michigan, served as Gotham Harbor in a climactic ferry scene. Scouts spent over a month searching for suitable vessels but were unsuccessful, so construction coordinator Joe Ondrejko and his team built ferry facades atop barges.[101][106] The entire sequence was filmed in one day and involved 800 extras, who were moved through makeup and clothing departments in shifts.[107] Exterior footage of the Gotham Prewitt Building, the site of the Batman's and the Joker's final confrontation, was filmed at the in-construction Trump International Hotel and Tower. The owners refused permission to film a stunt in which the Batman suspends a SWAT team from the building, so this was filmed from the fortieth floor of a separate building site.[108] A former Brach's candy factory on Cicero Avenue scheduled for demolition was used to film the Gotham General Hospital explosion in August 2007.[101][109] Filming in Chicago concluded on September 1, ending with scenes of Wayne driving and crashing his car, before the production returned to England.[101][110]

The Dark Knight includes Chicago locations such as Lake Michigan, which doubled as the Caribbean Sea where Wayne boards a seaplane;[107] Richard J. Daley Center (Wayne Enterprises exteriors and a courtroom);[101][111] The Berghoff restaurant (GCPD arresting mobsters);[101] Twin Anchors restaurant; the Sound Bar; McCormick Place (Wayne Enterprises interiors); and Chicago Theatre.[101] 330 North Wabash served as offices used by Dent, mayor Garcia, and commissioner Loeb; and its thirteenth floor appears as Wayne Enterprises' boardroom; Pfister enhanced its large, panoramic windows and natural light with an 80-foot (24 m) glass table and reflective bulbs.[99] A Randolph Street parking garage is where the Batman captures Scarecrow and Batman impersonators. Christopher wanted several Rottweiler dogs in the scene but locating a dog-handler willing to simultaneously manage several dogs was difficult.[101][112] A scene of the Batman surveying the city from a rooftop edge was filmed atop Willis Tower, Chicago's tallest building. Stuntman Buster Reeves was due to double as the Batman, but Bale persuaded the filmmakers to let him perform the scene himself.[101][113][114] The thirteen weeks of filming in Chicago was estimated to have generated $45 million for the city's economy and thousands of local jobs.[115][116]

Filming in England and Hong Kong

Many interior locations for The Dark Knight were filmed on sets at Pinewood Studios, Buckinghamshire, and Cardington Airfield, Bedfordshire; these locations include the Bat Bunker, which took six weeks to build in a Cardington hangar. The Bat Bunker was based on 1960s Chicago building designs, and was integrated into existing concrete floor, and used the 200-foot (61 m) long, 8 ft (2.4 m) tall ceiling to create a broad perspective. The 160-foot (49 m) tall hangar was unsuitable for suspending the bunker roof, and an encompassing gantry was built to hold it and the lighting.[81][117] After moving from Chicago in May, scenes filmed in the UK also include Criterion Restaurant, where Rachel, Dent, and Wayne share dinner, and a Gotham News scene that was filmed at the University of Westminster. The GCPD headquarters was rebuilt in the Farmiloe Building. During the interrogation scene, Ledger asked Bale to actually hit him, and although he declined, Ledger cracked and dented the walls by throwing himself around.[117][118]

After returning to England in the middle of September, scenes were filmed for the ferry, hospital, and Gotham Prewitt building interiors.[119] By mid-October, interior and exterior scenes of Rachel being held hostage surrounded by barrels of gasoline were filmed at Battersea Power Station. To avoid damaging the power station, a listed building, a false wall was built in front of it and lined with explosives.[120] Nearby residents contacted emergency services believing the explosion was a terrorist attack.[121] Filming in England concluded at the end of October with a variety of green-screen shots for the truck-chase sequence, and shots of Rachel being thrown from a window were filmed on a set at Cardington.[122]

The final nine days of production took place in Hong Kong and included aerial footage from atop the International Finance Centre, as well as filming at Central to Mid-Levels escalator, The Center, Central, The Peninsula Hong Kong, and Queen's Road; and a stunt involving the Batman catching an in-flight C-130 aircraft.[lower-alpha 21] Despite extensive rehearsals of Reeves jumping from the McClurg Building in Chicago, a planned stunt to depict the Batman leaping from one Hong Kong skyscraper to another was canceled because local authorities refused permission for helicopter use; Pfister described the officials as a "nightmare".[61][127] Christopher disputed a report that said a scene of the Batman leaping into Victoria Harbour was canceled because of pollution concerns, saying it was a script decision.[123][124] The 127-day shoot concluded on November 15, on time and under budget.[128]

Post-production

Editing was underway in January 2008 when Ledger, aged 28, died from an accidental overdose of a prescription drug. A rumor his commitment to his performance as the Joker had affected his mental state circulated, but this was later refuted.[lower-alpha 22] Christopher said editing the film became "tremendously emotional, right when he passed, having to go back in and look at him every day [during editing] ... but the truth is, I feel very lucky to have something productive to do, to have a performance that he was very, very proud of, and that he had entrusted to me to finish".[58] Because Christopher preferred to capture sound while filming rather than re-recording dialogue in post-production, Ledger's work had been completed before his death, and Christopher did not modify the Joker's narrative in response.[61][131] Christopher added a dedication to Ledger and stuntman Conway Wickliffe, who died during rehearsals for a Tumbler (Batmobile) stunt.[132][133][134]

Alongside lead editor Lee Smith, Christopher took an "aggressive editorial approach" to editing The Dark Knight to achieve its 152-minute running time.[lower-alpha 23] Christopher said no scenes were deleted because he believed every scene was essential, and that unnecessary material had been cut before filming. The Nolans had difficulties refining the script to reduce the running time but after removing so much material they believed it had become incomprehensible, they had added more scenes.[135][35]

Special effects and design

Unlike the design process of Batman Begins, which was restrained by a need to represent Batman iconography, audience acceptance of its realistic setting gave The Dark Knight more design freedom.[138] Chris Corbould, the film's special effects supervisor,[139] oversaw the 700 effect shots Double Negative and Framestore produced; there were relatively few effects compared to equivalent films because Christopher only used computer-generated imaging where practical effects would not suffice.[140] Production designer Nathan Crowley designed the Batpod (Batcycle) because Christopher did not want to extensively re-use the Tumbler. Corbould's team built the Batpod, which is based on a prototype Crowley and Christopher built by combining different commercial model components.[141][142] The unwieldy, wide-tired vehicle could only be ridden by stuntman Jean Pierre Goy after months of training.[114][142][143] The Gotham General Hospital explosion was not in the script but added during filming because Corbould believed it could be done.[144]

Hemming, Crowley, Christopher, and Jamie Rama re-designed the Batsuit to make it more comfortable and flexible, developing a costume made from a stretchy material covered in over 100 urethane armor pieces.[145][146] Sculptor Julian Murray developed Dent's burnt-facial design, which is based on Christopher's request for a skeletal appearance. Murray went through designs that were "too real and more horrifying" before settling on a more "fanciful" and detailed but less-repulsive version.[66][147] Hemming designed Joker's overall appearance, which he based on fashion-and-music celebrities to create a modern and trendy look. Influence also came from the 1953 painting Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X by Francis Bacon—suggested by Christopher—and the character's comic-book appearances.[34][148][149] The outfit consists of a purple coat, a green vest, an antique shirt, and a thin, 1960s-style tie that Ledger suggested.[150] Prosthetics supervisor Conor O'Sullivan created Joker's scars, which he partly based on a scarred delivery man he met, and used his own technique to create and apply the supple, skin-like prosthesis.[34][151] John Caglione Jr designed Joker's "organic" makeup to look as though it had been worn for days; this idea was partly based on more of Bacon's works. Caglione Jr used a theatrical makeup technique for the application; he instructed Ledger to scrunch up his face so different cracks and textures were created once the makeup was applied and Ledger relaxed. Ledger always applied the lipstick himself, believing it was essential to his characterization.[34][152][153]

Music

Composers James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer, who had also worked on Batman Begins, scored The Dark Knight because Christopher believed it was important to bridge the musical-narrative gap between the films. The score was recorded at Air Studios, London. Howard and Zimmer composed the score without seeing the film because Christopher wanted them to be influenced by the characters and story rather than fitting specific on-screen elements.[154][155] Howard and Zimmer separated their duties by character; Howard focused on Dent and Zimmer focused on the Batman and the Joker. Zimmer did not consider the Batman to be strictly noble and wrote the theme to not seem "super".[156][157] Howard wrote about ten minutes of music for Dent, wanting to portray him as an American who represents hope, but undergoes an emotional extreme and moral corruption. He used brass instruments for both moral ends but warped the sound as Dent is corrupted.[154][156]

Zimmer wanted to use a single note for the Joker's theme; he said, "imagine one note that starts off slightly agitated and then goes to serious aggravation and finally rips your head off at the end". He could not make it work, however, and used two notes with alternating tempos and a "punk" influence.[154][156][157] The theme was influenced by electronic music innovators Kraftwerk and Zimmer's work with rock band The Damned. He wanted to convey elements of the Joker's corrosion, recklessness, and "otherworldliness" by combining electronic and orchestral music, and modifying almost every note after recording to emulate sounds including thunder and razors.[154][157][158] He attempted to develop original sounds with synthesizers, trying to create an "offputting" result by instructing musicians to start with a single note and gradually shift to the second over a three-minute period; the musicians found this difficult because it was the opposite of their training.[156] It took several months to achieve Zimmer's desired result.[157] Following Ledger's death, Zimmer considered discarding the theme for a more traditional one but he and Howard believed they should honor Ledger's performance.[lower-alpha 24]

Release

Marketing and anti-piracy

_ARG_Example.jpeg.webp)

The Dark Knight's marketing campaign was developed by alternate reality game (ARG) development company 42 Entertainment. Christopher wanted the team to focus on countering the negative reaction to Ledger's casting and controlling the revelation of the Joker's appearance.[160] Influenced by the script and the comic books The Killing Joke, The Long Halloween, and Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989), 42 Entertainment paced the ARG over annual events, although Warner Bros. rejected their ideas to use Jokerized Santas at Christmas, coffins filled with chattering teeth on Mother's Day (mocking Wayne's late mother), and Batman actors on rooftops due to safety concerns.[160][161]

The ARG began in May 2007 with campaign posters for Dent and Joker playing cards bearing the phrase "I believe in Harvey Dent" were hidden inside comic books at stores around the U.S. This led people to a website where they could submit their e-mail addresses to reveal a pixel of a concealed Joker image; about 97,000 e-mail addresses and 20 hours were required to reveal the image in full, which was well received. At the San Diego Comic-Con, 42 Entertainment modified 11,000 one-dollar bills with the Joker's image and the phrase "Why So Serious?" that led finders to a location. 42 Entertainment's initial plan to throw the bills from a balcony was canceled due to safety concerns, so the bills were covertly distributed to attendees. Although the event was expected to attract a few thousand people, 650,000 arrived and participated in activities that included calling a number taken from a plane flying overhead and wearing Joker makeup to commit disruptive acts with actors.[160][161][162] Globally, fans photographed letters on signs to form a ransom note. A U.S.-centric effort involved people recovering cellphones made by Nokia—a brand partner to the film—from a cake, which led to an early screening of the film's bank-heist prologue before its public release in December. Ledger's appearance in the prologue was well-received and positively changed the discourse around his casting.[lower-alpha 25]

Following Ledger's death, the campaign continued unchanged with a focus on Dent's election, which was influenced by the ongoing 2008 United States presidential election. Warner Bros. was concerned public knowledge of Dent's character was poor; the campaign included signs, stickers, and "Dentmobiles" visiting U.S. cities to raise his profile. The campaign concluded in July with displays of the Bat-Signal in Chicago and New York City that were eventually defaced by the Joker. Industry professionals considered the campaign innovative and successful.[lower-alpha 26]

Warner Bros. dedicated six months to anti-piracy methods; the film industry lost an estimated $6.1 billion to piracy in 2005. Delivery methods of film reels were randomized and copies had a chain of custody to track who had access. Some theater staff were given night-vision goggles to identify people recording The Dark Knight, and one person was caught in Kansas City. Warner Bros. considered its strategy a success, delaying the appearance of the first "poorly-lit" camcorder version until 38–48 hours after its earliest global release in Australia.[172][173]

Context

Compared to 2007's $9.7 billion box-office take, in 2008, lower revenues were expected due to the large number of comedies competing against each other and the release of films with dark tones, such as The Dark Knight, during a period of rising living costs and election fatigue in the U.S. Fewer sequels, which generally performed well, were scheduled and only four—The Dark Knight, The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian, The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor, and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull—were predicted to be blockbusters. Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was the only film expected to easily earn over $300 million.[174]

The Dark Knight was expected to sell well based on high audience anticipation, positive pre-release reviews, and a record $3.5 million in IMAX pre-sales. Predictions placed its opening-weekend take above that of Iron Man's $102.1 million but below that of Spider-Man 3's (2007) record $151.1 million. Analysts said its success would be influenced by the lengthy running time that limited the number of screenings per day, and counter-programming from the romantic comedy Mamma Mia!—which surveyed well with women—and the family comedy Space Chimps. There was also a perceived limit on financial success for Batman films; the 1989 installment remained the franchise's highest-grossing release.[175][176] The Dark Knight's premiere took place on July 14, in IMAX in New York City. A block in Broadway was closed for the event, which included a live performance of the film score by Howard and Zimmer. The Hollywood Reporter said Ledger received several ovations, and that during the after-party, Warner Bros. executives struggled to maintain a balance between celebrating the successful response and commemorating Ledger.[177]

Box office

.jpg.webp)

On July 18, 2008, The Dark Knight was widely released in the U.S. and Canada in a record 4,366 theaters on an estimated 9,200 screens. It earned $158.4 million during the weekend, a per-theater average of $36,282, breaking Spider-Man 3's record and making it the number-one film ahead of Mamma Mia! ($27.8 million) and Hancock ($14 million) in its third weekend.[lower-alpha 27] It set further records for the highest-grossing single-day ($67.2 million on the Friday), Sunday ($43.6 million), midnight opening ($18.5 million, from 3,000 midnight screenings), and IMAX opening ($6.3 million from about 94 locations), as well as the second-highest-grossing Saturday ($47.7 million) behind Spider-Man 3, and contributed to the highest-grossing weekend on record ($253.6 million).[lower-alpha 28] The film benefited from repeat viewings by younger audiences and had broad appeal, with 52% of the audience being male and an equal number of those under 25 years old, and those of 25 or older.[175][176][184]

The Dark Knight broke more records, including for the highest-grossing opening week ($238.6 million), and for three-, four-, five-, six-, seven-, eight-, nine-, and ten-day cumulative grosses, including the highest-grossing non-holiday Monday ($24.5 million) and non-opening Tuesday ($20.9 million, as well as the second-highest-grossing non-opening Wednesday ($18.4 million), behind Transformers ($29.1 million).[lower-alpha 29] It retained the number-one position in its second weekend with a total gross of $75.2 million, ahead of the debuting Step Brothers ($31 million), giving it the highest-grossing second weekend.[189][190] It retained the number-one position in its third ($42.7 million) and fourth ($26.1 million) weekends, before falling to second place in its fifth, with a gross of $16.4 million, behind the debuting Tropic Thunder ($25.8 million).[191][192][193] The Dark Knight remained in the top-ten highest-grossing films for ten weeks, and became the film to surpass $400 million soonest (18 days) and $500 million (45 days).[179][194][195] The film was playing in fewer than 100 theaters when it received a 300-theater relaunch in late January 2009 to raise its profile during nominations for the 81st Academy Awards. This raised its total box office to $533.3 million before it left theaters on March 5 after 33 weeks, making it the highest-grossing comic-book, superhero, and Batman film; the highest-grossing film of 2008; and the second-highest-grossing film ever (unadjusted for inflation), behind the 1997 romantic drama Titanic ($600.8 million).[lower-alpha 30]

The Dark Knight was released in Australia and Taiwan on Wednesday, July 16, 2008, and opened in twenty markets by the weekend. It earned about $40 million combined, making it second to Hancock ($44.8 million), which was playing in nearly four times as many countries.[lower-alpha 31] The Dark Knight was available in sixty-two countries by the end of August, although Warner Bros. decided not to release it in China, blaming "a number of pre-release conditions ... as well as cultural sensitivities to some elements of the film".[206] The Dark Knight earned about $469.7 million outside the U.S. and Canada, its highest grosses coming from the United Kingdom ($89.1 million), Australia ($39.9 million), Germany ($29.7 million), France ($27.5 million), Mexico ($25 million), South Korea ($24.7 million), and Brazil ($20.2 million). This made it the second-highest-grossing film of the year behind Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.[202][207]

The film had grossed $997 million worldwide by January 2009.[201][208] Its reissue in the run-up to the Oscars enabled the film to exceed $1 billion in February,[209] and it ultimately earned $1.003 billion. It was the first superhero film to gross over $1 billion, the highest-grossing film of 2008 worldwide, the fourth film to earn more than $1 billion, and the fourth-highest-grossing film of its time behind Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest ($1.066 billion), The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King ($1.119 billion), and Titanic ($1.842 billion).[lower-alpha 32][lower-alpha 33] As of September 2022, rereleases have further raised its box-office take to $1.006 billion.[91]

Reception

Critical response

_revised.jpg.webp)

The Dark Knight received critical acclaim.[lower-alpha 34] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 94% approval rating from the aggregated reviews of 345 critics, with an average score of 8.6/10. The consensus reads; "Dark, complex and unforgettable, The Dark Knight succeeds not just as an entertaining comic book film, but as a richly thrilling crime saga."[218] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 84 out of 100 based on 39 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[217] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[219]

Several publications called The Dark Knight the best comic-book hero adaptation ever made. Roger Ebert said it, alongside Iron Man, had redefined the potential of superhero films by combining comic-book tropes with real world events.[lower-alpha 35] Some appreciated its complex moral tale about the effects of vigilantism and terrorism on contemporary society. Emanuel Levy and Manohla Dargis praised the depiction of the characters as possessing both positive and negative aspects, such as the Batman's efforts to end crime provoking unintended consequences and a greater response from criminals; Dargis believed The Dark Knight's exploration of chaos, fear, and death, following the September 11 attacks in 2001, represented "that American movies have entered a new era of ambivalence when it comes to their heroes or maybe just superness."[lower-alpha 36] Others criticized the dark, grim, intense, and self-serious tone as lacking any elements of fun or fantasy.[lower-alpha 37] David Denby said The Dark Knight was a product of a "time of terror", but focused on embracing and unleashing it while cynically setting up a sequel.[210] Stephanie Zacharek and David Edelstein criticized a perceived lack of visual storytelling in favor of exposition, and aspects of the plot being difficult to follow amid the fast pace and loud score.[232][233] Christopher's action direction was criticized, especially during fight scenes where it could be difficult to see things clearly,[227][228] although the prologue bank heist was praised as among the film's best.[lower-alpha 38]

Ledger's performance received near-unanimous praise with the caveat that his death made the role both highly anticipated and difficult to watch.[lower-alpha 39] Dargis, among others, described Ledger as realizing the Joker so convincingly, intensely, and viscerally it made the audience forget about the actor behind the makeup. The Village Voice wrote the performance would have made Ledger a legend even if he had lived.[lower-alpha 40] Other reviews said Ledger outshone Nicholson's "magnificent" performance with macabre humor and malevolence.[222][235][239] Reviews generally agreed the Joker was the best-written character, and that Ledger commanded scenes from the entire cast to create one of the most mesmerizing cinematic villains.[lower-alpha 41] Zacharek, however, lamented that the performance was not in service of a better film.[233]

Bale's reception was mixed; his performance was considered to be alternately "captivating" or serviceable, but ultimately uninteresting and undermined by portraying an immovable and generally unchanged character who delivers the Batman's dialogue in a hoarse, unvarying tone.[lower-alpha 42] Eckhart's performance was generally well received; reviewers praised his portrayal of Dent as charismatic, and the character's subsequent transformation into a sad, bitter "monster", although Variety considered his subplot the film's weakest.[lower-alpha 43] Stephen Hunter said the Dent character was underwritten and that Eckhart was incapable of portraying the role as intended.[234] Several reviewers regarded Gyllenhaal as an improvement over Holmes, although others said they found difficulty caring about the character and that Gyllenhaal, while more talented than her predecessor, was miscast.[lower-alpha 44] Peter Travers praised Oldman's skill in making a virtuous character interesting and he, among others, described Caine's and Freeman's performances as "effortless".[220][223][233] Ebert surmised the entire cast provided "powerful" performances that engage the audience, such that "we're surprised how deeply the drama affects us".[210]

Accolades

The Dark Knight appeared on several lists recognizing the best films of 2008, including those compiled by Ebert, The Hollywood Reporter, and the American Film Institute.[lower-alpha 45] At the 13th Satellite Awards, The Dark Knight received one award for Sound Editing or Mixing (Richard King, Lora Hirschberg, Gary Rizzo).[249] A further four wins came at the 35th People's Choice Awards: Favorite Movie, Favorite Cast, Favorite Action Movie, and Favorite On-Screen Match-Up (Bale and Ledger),[250] as well as Best Action Movie and Best Supporting Actor (Ledger) at the 14th Critics' Choice Awards.[251] Howard and Zimmer were recognized for Best Motion Picture Score at the 51st Annual Grammy Awards.[252] Ledger won the film's only awards at the 15th Screen Actors Guild Awards, 62nd British Academy Film Awards, and 66th Golden Globe Awards, for Best Supporting Actor.[253][254][255] At the 14th Empire Awards, The Dark Knight received awards for Best Film, Best Director (Christopher Nolan), and Best Actor (Bale).[256] Ledger received the award for Best Villain at the 2009 MTV Movie Awards,[257] and at the 35th Saturn Awards, The Dark Knight won awards for Best Action or Adventure Film, Best Supporting Actor (Ledger), Best Writing (Christopher and Jonathan Nolan), Best Music (Howard and Zimmer), and Best Special Effects (Corbould, Nick Davis, Paul J. Franklin, Timothy Webber).[258]

Before The Dark Knight's release, film industry discourse focused on Ledger potentially earning an Academy Award nomination at the 81st Academy Awards in 2009, making him only the seventh person to be nominated posthumously, and if the decision would be influenced by his passing or performance.[lower-alpha 46] Genre films such as those based on comic books were also generally ignored by Academy voters.[267][268][269] Even so, Ledger was considered a favorite to earn the award based on praise from critic groups and his posthumous Golden Globe award.[261][262][263] Ledger won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, making him only the second performer to win an award posthumously (after Peter Finch in 1977), and The Dark Knight the first comic book adaptation to win an academy acting award.[261][270][271] The Dark Knight also won an award for Best Sound Editing (King), and received six nominations for Best Art Direction (Crowley and Peter Lando), Best Cinematography (Pfister), Best Film Editing (Smith), Best Makeup (Caglione Jr. and O'Sullivan), Best Sound Mixing (Hirschberg, Rizzo, and Ed Novick), and Best Visual Effects (Davis, Corbould, Webber, and Franklin).[272]

Despite the success of The Dark Knight, the lack of a Best Picture nomination was criticized and described as a "snub" by some publications. The response was seen as the culmination of several years of criticism toward the academy ignoring high-performing, broadly popular films.[273][274][275] The backlash was such that, for the 82nd Academy Awards awards in 2010, the academy increased the limit for Best Picture nominees from five to ten, a change known as "The Dark Knight Rule". It allowed for more broadly popular but "respected" films to be nominated, including District 9, The Blind Side, Avatar, and Up, the first animated film to be nominated in two decades.[lower-alpha 47] This change is seen as responsible for the first Best Picture nomination of a comic book adaptation, Black Panther (2018).[276][284] Even so, The Hollywood Reporter argued the academy mistook the appeals to recognize important, "generation-defining" genre films with just nominating more films.[285]

Other releases

Home media

The Dark Knight was released on DVD and Blu-ray in December 2008. The release has a slipcover box-art that revealed a "Jokerized" version underneath, and contains featurettes on the Batman's equipment, the psychology used in the film, six episodes of the fictional news program Gotham Tonight, and a gallery of concept art, posters, and Joker cards. The Blu-ray disc version additionally offers interactive elements describing the production of some scenes.[lower-alpha 48] A separate, limited-edition Blu-ray disc set came with a Batpod figurine.[289] The Dark Knight sold 3 million copies across both formats on its launch day in the U.S., Canada, and the UK; Blu-ray discs comprised about 25–30% of the sales—around 600,000 units. The film was released at the beginning of the Blu-ray disc format; it was considered a success, breaking Iron Man's record of 250,000 units sold and indicating the format was growing in popularity.[lower-alpha 49] In 2011, it also became the first major-studio film to be released for rent via digital distribution on Facebook.[294] A 4K resolution remaster, which was overseen by Christopher, was released in December 2017 as a set containing a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray, Blu-ray disc, and digital download, as well as special features from earlier releases.[295][296][297]

Merchandise and spin-offs

Merchandise for The Dark Knight includes statuettes, action figures, radio-controlled Tumbler and Batpod models, costumes, sets of Batarangs, a limited-edition Grappling Launcher replica, board games, puzzles, clothing, and a special-edition UNO card game.[lower-alpha 50] A novelization written by Dennis O'Neil was released in 2008.[302]

A direct-to-DVD animated film, Batman: Gotham Knight, was released in July 2008. Executive produced by Bruce Timm and Nolan's wife Emma Thomas, with Goyer as one of the writers, it includes veteran Batman voice actor Kevin Conroy reprising his role. Originally there was interest in bringing Bale and other actors from the live-action films to voice their respective characters, but it was not possible due to scheduling conflicts. Gotham Knight presents six vignettes, each of which are animated in a different artistic style, set between the events of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.[303][304]

A video game adaptation, Batman: The Dark Knight, was canceled due to development problems.[305][306] The Dark Knight Coaster, an indoor roller coaster, opened in May 2008 at Six Flags Great Adventure in Jackson Township, New Jersey. Costing $7.5 million, the 1,213-foot (370 m) long attraction places riders in an imitation of Wayne Central Station in Gotham City as they move through areas that are vandalized or controlled by the Joker.[307][308]

Themes and analysis

Terrorism and escalation

A central theme of The Dark Knight is escalation, particularly the rise of the Joker in response to the Batman's vigilantism.[309][310] The Batman's vigilante operation arms him with high-tech military equipment against common criminals, and the Joker is the inevitable response and escalation of lawlessness to counter the Batman. Critic Siddhant Adlakha considered the Joker an analog for countries such as Iraq, Somalia, and Lebanon, which were targeted by U.S. military campaigns and responded with escalation using terrorism.[310] The Batman also inspires copycat vigilantes, further escalating lawlessness. Film studies professor Todd McGowan said the Batman asserts authority over these copycats, telling them to stop because they do not have the same defensive equipment as himself, reaffirming his self-given authority to act as a vigilante.[311]

The film has been analyzed as an analog for the war on terror, the militaristic campaign the U.S. launched following the September 11 attacks.[310] The scene in which the Batman stands in the ruins of a destroyed building, having failed to prevent the Joker's plot, is reminiscent of the World Trade Center site after September 11.[310] According to historian Stephen Prince, The Dark Knight is about the consequences of civil and government authorities abandoning rules in the fight against terrorism.[312] Several publications criticized The Dark Knight for a perceived endorsement of "necessary evils" such as torture and rendition.[313] Author Andrew Klavan said the Batman is a stand-in for then-U.S. president George W. Bush and justified the breaching of "boundaries of civil rights to deal with an emergency, certain that [the Batman] will re-establish those boundaries when the emergency is past".[311][314] Klavan's interpretation was criticized by some publications that considered The Dark Knight anti-war, proposing society must not abandon the rule of law to combat lawlessness or risk creating the conditions for escalation.[315][316] This is exemplified in the covert alliance formed between the Batman, Dent, and Gordon, leading to Rachel's death and Dent's corruption.[313] Writer Benjamin Kerstein said both viewpoints are valid, and that "The Dark Knight is a perfect mirror of the society which is watching it: a society so divided on the issues of terror and how to fight it that, for the first time in decades, an American mainstream no longer exists".[317]

The Batman and Dent resort to torture or enhanced interrogation to stop the Joker but he remains immune to their efforts because he has a strong belief in his goals. When Dent ineffectually attempts to torture Joker's henchman, the Batman does not condemn the act, only being concerned about public perception if people discover the truth. This conveys the protagonists' gradual abandonment of their principles when faced with an extreme foe.[310] The Joker meets Dent in a hospital to explain how expected atrocities, such as the deaths of several soldiers, and societal failings are tolerated but when norms are unexpectedly disrupted, people panic and descend into chaos.[310][318] Although the Joker wears disguising makeup, he is not hiding behind a mask and is the same person with or without makeup. He lacks any identity or origin, representing the uncertainty, unknowability, and fear of terrorism, although he does not follow any political ideology.[310][319] Dent represents the fulfillment of American idealism, a noble person who can work within the confines of the law and allow the Batman to retire, but the fear and chaos embodied by the Joker taints that idealism and corrupts Dent absolutely.[310]

In The Dark Knight's final act, the Batman employs an invasive surveillance network by co-opting the phones of Gotham's citizens to locate the Joker, violating their privacy. Adlakha described this act as a "militaristic fantasy", in which a significant violation of civil liberties is required through the means of advanced technology to capture a dangerous terrorist, reminiscent of the 2001 Patriot Act. Lucius Fox threatens to stop helping the Batman in response, believing he has crossed an ethical boundary, and although the Batman agrees these violations are unacceptable and destroys the technology, the film demonstrates he could not have stopped the Joker in time without it.[310][311]

Morality and ethics

The Dark Knight focuses on the moral and ethical battles faced by the central characters, and the compromises they make to defeat the Joker under extraordinary circumstances.[lower-alpha 51] Roger Ebert said the Joker forces impossible ethical decisions on each character to test the limits of their morality.[220][310] The Batman represents order to the Joker's chaos and is brought to his own limit but avoids completely compromising himself. Dent represents goodness and hope; he is the city's "white knight" who is "pure" of intent and can operate within the law.[310][311][318] Dent is motivated to do good because he identifies himself as good, not through trauma like the Batman, and has faith in the legal system.[311] Adlakha wrote Dent is framed as a religious icon, his campaign slogan being "I believe in Harvey Dent", and his eventual death leaves his arms spread wide like Jesus on the Cross.[310][318] Eckhart described Dent as someone who loves the law but feels constrained by it and his inability to do what he believes is right because the rules he must follow do not allow it.[66] Dent's desire to work outside the law is seen in his support of the Batman's vigilantism to accomplish what he cannot.[42]

Dent's corruption suggests he is a proxy for those looking for hope because he is as fallible and susceptible to darkness as anyone else.[318] This can be seen in his use of a two-headed coin to make decisions involving others, eliminating the risk of chance by controlling the outcome in his favor, indicating losing is not an acceptable outcome for him. Once Dent experiences a significant traumatic event in the loss of Rachel and his own disfigurement, he quickly abandons his noble former self to seek his own form of justice. His coin is scarred on one side, introducing the risk of chance, and he submits himself to it completely. According to English professor Daniel Boscaljon, Dent is not broken; he believes in a different form of justice in a seemingly unjust world, flipping a coin because it is "Unbiased. Unprejudiced. Fair."[321]

The Joker represents an ideological deviancy; he does not seek personal gain and causes chaos for its own sake, setting a towering pile of cash ablaze to prove "everything burns". Unlike the Batman, the Joker is the same with or without makeup, having no identity to conceal and nothing to lose.[lower-alpha 52] Boscaljon wrote the residents and criminals believe in a form of order and rules that must be obeyed; the Joker deliberately upends this belief because he has no rules or limitations.[323] The character can be considered an example of Friedrich Nietzsche's "Superman", who exists outside definitions such as good and evil, and follows his own indomitable will. The film, however, leaves open the option to dismiss his insights because his chaos ultimately leads to death and injustice.[324] Christopher described the Joker as an unadulterated evil, and professor Charles Bellinger considered him a satanic figure who repels people from goodness and tempts them with things they supposedly lack, such as forcing the Batman to choose between saving Dent—who is best for the city—and Rachel, who is best for Wayne.[325] The Joker aims to corrupt Dent to prove anyone, even symbols, can be broken. In their desperation, Dent and the Batman are forced to question their own limitations. As the Joker states to the Batman:

Their morals, their code ... it's a bad joke. Dropped at the first sign of trouble. They're only as good as the world allows them to be. You'll see—I'll show you ... when the chips are down, these civilized people ... they'll eat each other. See, I'm not a monster ... I'm just ahead of the curve.

The ferry scene can be seen as the Joker's true defeat, demonstrating he is wrong about the residents turning on each other in an extreme scenario.[310][318] According to writer David Chen, this demonstrates, individually, people cannot responsibly handle power but by sharing the responsibility, there is hope for a compassionate outcome.[318] Although the Batman holds to his morals and does not kill the Joker, he is forced to break his code by pushing Dent to his death to save an innocent person. The Batman chooses to become a symbol of criminality by taking the blame for Dent's crimes and preserving him as a symbol of good, maintaining the hope of Gotham's residents.[310][311][318] Critic David Crow wrote the Batman's true test is not defeating the Joker but saving Dent, a task at which he fails.[327] The Batman makes his own Christ-like sacrifice, taking on Dent's sins to preserve the city.[324]

Although The Dark Knight presents this as a heroic act, this "noble lie" is used to conceal and manipulate the truth for what a minority determines is the greater good.[311][328] McGowan considered the act heroic because the Batman's sacrifice will leave him hunted and despised without recognition, indicating he has learned from the Joker the established norms must sometimes be broken.[311] According to professor Martin Fradley, among others, the Batman's "noble lie" and Gordon's support of it is a cynical endorsement of deception and totalitarianism.[311][328] Wayne's butler Alfred also commits a noble lie, concealing Rachel's choice of Dent over Wayne to spare him the pain of her rejection.[310]

Legacy

Cultural influence

The Dark Knight is considered an influential and often-imitated work that redefined the superhero/comic-book film genre, and filmmaking in general.[lower-alpha 53] In 2020, the United States Library of Congress selected The Dark Knight to be preserved in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[331]

Before The Dark Knight, superhero films closely emulated their comic-book source material, and though the genre had seen significant successes such as Superman (1978), Batman (1989), X-Men (2000), and Spider-Man (2002), they were often considered disposable entertainment that did not garner much industry respect.[lower-alpha 54] A 2018 retrospective by The Hollywood Reporter said The Dark Knight taught filmmakers "comic book characters are malleable. They are able to be grounded or fantastic, able to be prestigious or pure blockbuster entertainment, to be dark and gritty or light, to be character-driven or action-packed, or any variation in-between."[285]

The Dark Knight is considered a blueprint for the modern superhero film that productions either attempt to closely emulate or deliberately counter.[lower-alpha 55] Its financial, critical, and cultural successes legitimized the genre with film studios at a time when recent films, such as Daredevil, Hulk (both 2003), Fantastic Four (2005), and Superman Returns (2006) had failed to meet expectations.[275][333] The genre became a focus of annual studio strategies rather than a relatively niche project, and a surge of comic-book adaptations followed, in part because of their broad franchising potential. In 2008, Ebert wrote; "[The Dark Knight], and to a lesser degree Iron Man, redefine the possibilities of the 'comic-book movie'".[210] The Atlantic wrote Iron Man's legacy in launching the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) could not have happened without the financial and critical success of The Dark Knight, which made comic book adaptations a central focus of film studios.[184][275][285]

Retrospective analysis has focused on the way studios, eager to replicate its performance, released tonally dark, gritty, and realistic films, or reboots of existing franchises, many of which failed critically or commercially.[277][285][329] Some publications said studios took the wrong lessons from The Dark Knight, treating source material too seriously and mistaking a dark, gritty tone for narrative depth and intelligent writing.[lower-alpha 56] The MCU is seen as a successful continuation of what made The Dark Knight a success, combining genres and tones relevant to each respective film while treating the source material seriously, unlike the DC Extended Universe, which more closely emulated the tone of The Dark Knight but failed to replicate its success.[329][335]

Directors including Sam Mendes (Skyfall, 2012), Ryan Coogler (Black Panther), and David Ayer (Suicide Squad, 2016), have cited it as an influence on their work, and Steven Spielberg listed it among his favorite films.[lower-alpha 57] The film has been referenced in a variety of media including television shows such as Robot Chicken, South Park, and The Simpsons.[339][340][341] U.S. President Barack Obama used Joker to explain the growth of Islamic State (IS) military group, saying " ... the gang leaders of Gotham are meeting ... they were thugs, but there was a kind of order ... the Joker comes in and lights the whole city on fire. [IS] is the Joker."[342] Joker's appearance became a popular Halloween costume and also influenced the 2009 Barack Obama "Joker" poster.[lower-alpha 58]

Retrospective assessments

Since its release, The Dark Knight has been assessed as one of the greatest superhero films ever made,[lower-alpha 59] among the greatest films ever made,[lower-alpha 60] and one of the best sequel films.[lower-alpha 61] It is also considered among the best films of the 2000s,[lower-alpha 62] and in a 2010 poll of thirty-seven critics by Metacritic regarding the decade's top films, The Dark Knight received the eighth most mentions, appearing on 7 lists.[373] In the 2010s, a poll of 177 film critics by the BBC in 2016 listed it as the 33rd-best film of the 21st century,[374] and The Guardian placed it 98th on its own list.[375] In 2020, Empire magazine named it third-best, behind The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015).[376] As of 2022, it remains the highest critically rated Batman film according to Rotten Tomatoes, and is often ranked as the best film featuring the character.[lower-alpha 63]

The Dark Knight remains popular with entertainment industry professionals, including directors, actors, critics, and stunt actors, being ranked 57th on The Hollywood Reporter's poll of the best films ever made,[357] 18th on Time Out's list of the best action films,[388] and 96th on the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest American Films.[358] The Dark Knight is included in the film-reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die,[389] and film critics James Berardinelli and Barry Norman included it in their individual listings of the 100 greatest films of all time.[359][360] In 2012, Total Film named it the sixth-most-accomplished film of the preceding fifteen years, and a 2020 article by Empire named The Dark Knight as one of the films that defined the previous three decades.[390][391] In 2020, Time Out named it the seventy-second-best action movie ever made.[392]

Ledger's Joker is considered one of the greatest cinematic villains; several publications placed his portrayal second only to Darth Vader.[lower-alpha 64] In 2017, The Hollywood Reporter named Ledger's Joker the second-best cinematic superhero performance ever, behind Hugh Jackman as Wolverine,[398] and Collider listed him as the greatest villain of the 21st century.[399] In 2022, Variety listed him as the best superhero film performance of the preceding 50 years (Eckhart appears at number 22).[400] Entertainment Weekly wrote there had not been another villain as interesting or "perversely entertaining" as Joker, and Ledger's performance was considered so defining that future interpretations would be compared against it. Michael B. Jordan cited the character as an inspiration for his character Erik Killmonger in Black Panther.[lower-alpha 65] The "pencil trick" scene, in which Joker makes a pencil disappear by slamming a mobster's head on it, is considered an iconic scene and among the film's most famous.[lower-alpha 66] Similarly, the character's line "why so serious?" is among the film's most famous and oft-quoted pieces of dialog,[lower-alpha 67] alongside "everyone loses their minds," and Dent's line "you either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain", as well as Pennyworth's line "some men just want to watch the world burn"; the lines also became popular internet memes.[lower-alpha 68]

The Dark Knight remains popular with audiences in publicly voted rankings. Over 17,000 people voted the film into the top ten of American Cinematographer's "Best-Shot Film of 1998–2008" list,[411] and listeners of BBC Radio 1 and BBC Radio 1Xtra named it their eighth-favorite film.[412] Readers of Empire have alternatively voted it the fifteenth (2008),[413] third (2014),[414] and the fourth-greatest film ever made (2020).[415] The Dark Knight was also voted the greatest superhero movie by readers of Rolling Stone (2014),[416] and as one of New Zealand's favorite films (2015).[417]

Sequel

The Dark Knight was followed by The Dark Knight Rises (2012), the conclusion of The Dark Knight Trilogy. In the film, the Batman is forced out of his self-imposed retirement following the events of The Dark Knight; he allies with Selina Kyle / Catwoman to take on Bane, a physically imposing revolutionary allied with the League of Shadows that is featured in Batman Begins.[418][419][420] The Dark Knight Rises was a financial success, surpassing the box-office take of The Dark Knight,[421] and was generally well received by critics but proved more divisive with audiences.[lower-alpha 69]

Notes

- Warner Bros. Pictures and Legendary Pictures serve as co-financiers and co-production companies for The Dark Knight, while Syncopy is credited as the production company.[1][2]

- The Dark Knight is considered a co-production of the United States and United Kingdom.[2][3]

- This figure represents the cumulative total accounting for the initial worldwide 2008 gross of $997 million and subsequent releases thereafter.

- Attributed to multiple references:[2][16][17][18][19][20]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][35][38][39][40]

- Attributed to multiple references:[35][38][39][40]

- Attributed to multiple references:[35][38][42][43]

- Attributed to multiple references:[10][35][44][45]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][35][38][39][46]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][35][38][39]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][38][52][53]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][38][53][54]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][56][57][58][59]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][55][60][61]

- Attributed to multiple references:[62][63][64][65]

- Attributed to multiple references:[35][70][71][72][73]

- Attributed to multiple references:[81][82][83][84]

- Attributed to multiple references:[81][84][85][86][87]

- Attributed to multiple references: [90][91][92][93]

- The 2008 budget of $185 million is equivalent to $251 million in 2022.

- Attributed to multiple references:[123][124][125][126]

- Attributed to multiple references:[49][61][129][130]

- Attributed to multiple references:[131][135][136][137]

- Attributed to multiple references:[154][156][157][159]

- Attributed to multiple references:[34][160][163][164][165][166]

- Attributed to multiple references:[160][161][167][168][169][170][171]

- Attributed to multiple references:[175][176][178][179][180]

- Attributed to multiple references:[175][181][182][183]

- Attributed to multiple references:[175][185][186][187][188]

- Attributed to multiple references:[179][196][197][198][199][200][201]

- Attributed to multiple references:[176][202][203][204][205]

- Attributed to multiple references:[201][207][210][211][212]

- The 2008 box office gross of $1.003 billion is equivalent to $1.36 billion in 2022.

- Attributed to multiple references:[213][214][215][216][217]

- Attributed to multiple references:[220][221][222][223][224][225][226]

- Attributed to multiple references:[220][222][227][228][229][230][231]

- Attributed to multiple references:[221][227][228][229][231]

- Attributed to multiple references:[221][223][234][235]

- Attributed to multiple references:[220][221][222][223][225][228][231][233][235][236][237][238][239][227]

- Attributed to multiple references:[229][234][235][238]

- Attributed to multiple references:[220][224][230][234][236][239][240]

- Attributed to multiple references:[228][233][234][241]

- Attributed to multiple references:[220][223][229][235]

- Attributed to multiple references:[229][233][234][235][236]

- Attributed to multiple references:[242][243][244][245][246][247][248]

- Attributed to multiple references:[259][260][261][262][263][264][265][266]

- Attributed to multiple references:[276][277][278][279][280][281][275][282][283]

- Attributed to multiple references:[226][286][287][288]

- Attributed to multiple references:[290][291][292][293]

- Attributed to multiple references:[298][299][300][301]

- Attributed to multiple references:[220][310][318][320]

- Attributed to multiple references:[311][318][320][322]

- Attributed to multiple references:[275][277][320][329][330]

- Attributed to multiple references:[210][276][285][332]

- Attributed to multiple references:[276][277][320][330]

- Attributed to multiple references:[320][329][330][334]

- Attributed to multiple references:[330][336][337][338]

- Attributed to multiple references:[278][285][280][330][332][343]

- Attributed to multiple references:[344][345][346][347][348][349][350][351][352][353][354][355]

- Attributed to multiple references:[356][357][358][359][360][361]

- Attributed to multiple references:[362][363][364][365][366][367]

- Attributed to multiple references:[368][369][370][371][372]

- Attributed to multiple references:[377][378][379][380][381][382][383][384][385][386][387]