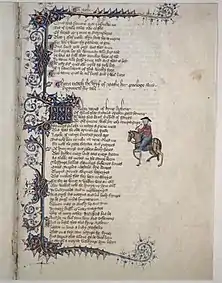

The Wife of Bath's Tale

"The Wife of Bath's Tale" (Middle English: The Tale of the Wyf of Bathe) is among the best-known of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. It provides insight into the role of women in the Late Middle Ages and was probably of interest to Chaucer himself, for the character is one of his most developed ones, with her Prologue twice as long as her Tale. He also goes so far as to describe two sets of clothing for her in his General Prologue. She holds her own among the bickering pilgrims, and evidence in the manuscripts suggests that although she was first assigned a different, plainer tale—perhaps the one told by the Shipman—she received her present tale as her significance increased. She calls herself both Alyson and Alys in the prologue, but to confuse matters these are also the names of her 'gossib' (a close friend or gossip), whom she mentions several times, as well as many female characters throughout The Canterbury Tales.

Geoffrey Chaucer wrote the "Prologue of the Wife of Bath's Tale" during the fourteenth century at a time when the social structure was rapidly evolving[1] during the reign of Richard II; it was not until the late 1380s to mid-1390s when Richard's subjects started to take notice of the way in which he was leaning toward bad counsel, causing criticism throughout his court.[2] It was evident that changes needed to be made within the traditional hierarchy at the court of Richard II; feminist reading of the tale argues that Chaucer chose to address through "The Prologue of the Wife of Bath's Tale" the change in mores that he had noticed, in order to highlight the imbalance of power within a male-dominated society.[3] Women were identified not by their social status and occupations, but solely by their relations with men: a woman was defined as either a maiden, a spouse or a widow – capable only of child-bearing, cooking and other "women's work".[4]

The tale is often regarded as the first of the so-called "marriage group" of tales, which includes the Clerk's, the Merchant's and the Franklin's tales. But some scholars contest this grouping, first proposed by Chaucer scholar Eleanor Prescott Hammond and subsequently elaborated by George Lyman Kittredge, not least because the later tales of Melibee and the Nun's Priest also discuss this theme.[5] A separation between tales that deal with moral issues and ones that deal with magical issues, as the Wife of Bath's does, is favoured by some scholars.

The tale is an example of the "loathly lady" motif, the oldest examples of which are the medieval Irish sovereignty myths such as that of Niall of the Nine Hostages. In the medieval poem The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle, Arthur's nephew Gawain goes on a nearly identical quest to discover what women truly want after he errs in a land dispute, although, in contrast, he never stooped to despoliation or plunder, unlike the unnamed knight who raped the woman. By tradition, any knight or noble found guilty of such a transgression (abuse of power) might be stripped of his name, heraldic title and rights, and possibly even executed.

Jodi-Anne George suggests that the Wife's tale may have been written to ease Chaucer's guilty conscience. It is recorded that in 1380 associates of Chaucer stood surety for an amount equal to half his yearly salary for a charge brought by Cecily Champaign for "de rapto", rape or abduction; the same view has been taken of his Legend of Good Women, which Chaucer himself describes as a penance.[6]

Scholarly work reported in October 2022 refutes this, stating that the court documents from 1380 have been misinterpreted and that mention of "raptus" were related to a labor dispute in which Chaucer hired a Cecily Chaumpaigne before she was released from her previous employer.[7][8]

Synopsis

Prologue

The Wife of Bath's Prologue is by far the longest in The Canterbury Tales and is twice as long as the actual story, showing the importance of the prologue to the significance of the overall tale. In the beginning the wife expresses her views in which she believes the morals of women are not merely that they all solely desire "sovereignty", but that each individual woman should have the opportunity to make the decision. The Wife of Bath speaks against many of the typical customs of the time, and provides her assessment of the roles of women in society.[1]

The Wife of Bath particularly speaks out in defence of those who, like her, have married multiple times. As a counterargument, she mentions many holy men who have had multiple wives:

| I woot wel Abraham was an holy man, And Iacob eek, as ferforth as I can; And ech of hem hadde wyves mo than two; And many another holy man also. Whan saugh ye ever, in any maner age, That hye God defended mariage By expres word? I pray you, telleth me; Or wher comanded he virginitee? |

I know well that Abraham was a holy man, and Jacob as well, as far as I know, and each of them had more than two wives, and many other holy men did as well. When have you seen that in any time great God forbade marriage explicitly? Tell me, I pray you, Or where did He order people to remain virgins?[9] |

Through this quote, she addresses why society should not look down on her or any other woman who has wed to multiple men throughout their life. The tale confronts the double standard and the social belief in the inherent inferiority of women, and tries to establish a defence of secular women's sovereignty that opposes the conventions available to her.[10]

Tale

The Wife of Bath's tale, spoken by one who had been married five times, argues that women are morally identical to men who have also had more than one spouse.[1] Double standards for men and women were common and deeply rooted in culture.

A knight in King Arthur's time raped a fair young maiden. King Arthur issues a decree that the knight must be brought to justice. When the knight is captured, he is condemned to death, but Queen Guinevere intercedes on his behalf and asks the King to allow her to pass judgment upon him. The Queen tells the knight that he will be spared his life if he can discover for her what it is that women most desire, and allots him a year and a day in which to roam wherever he pleases and return with an answer.

Everywhere the knight goes he explains his predicament to the women he meets and asks their opinion, but "No two of those he questioned answered the same." The answers range from fame and riches to play, or clothes, or sexual pleasure, or flattery, or freedom. When at last the time comes for him to return to the Court, he still lacks the answer he so desperately needs.

Outside a castle in the woods, he sees twenty-four maidens dancing and singing, but when he approaches they disappear as if by magic, and all that is left is an old woman. The Knight explains the problem to the old woman, who is wise and may know the answer, and she forces him to promise to grant any favour she might ask of him in return. With no other options left, the Knight agrees. Arriving at the court, he gives the answer that women most desire sovereignty over their husbands, which is unanimously agreed to be true by the women of the court who, accordingly, free the Knight.

The old woman then explains to the court the deal she has struck with the Knight, and publicly requests his hand in marriage. Although aghast, he realizes he has no other choice and eventually agrees. On their wedding night the old woman is upset that he is repulsed by her in bed. She reminds him that her looks can be an asset—she will be a virtuous wife to him because no other men would desire her. She asks him which one he would prefer—an old and ugly wife who is true and loyal, or a beautiful and young woman, who may not be faithful. The Knight responds by saying that the choice is hers. Happy that she now has the ultimate power, he having taken to heart the lesson of sovereignty and relinquished control, rather than choosing for her, she promises him both beauty and fidelity. The Knight turns to look at the old woman again, but now finds a young and lovely woman. The old woman makes "what women want most" and the answer that she gave true to him, sovereignty.[5]

The Wife of Bath ends her tale by praying that Jesus Christ bless women with meek, young, and submissive husbands and the grace to break them.

Themes

Feminist critique

The Wife of Bath's Prologue simultaneously enumerates and critiques the long tradition of misogyny in ancient and medieval literature. As Cooper notes, the Wife of Bath's "materials are part of the vast medieval stock of antifeminism",[11] giving St. Jerome's Adversus Jovinianum, which was "written to refute the proposition put forward by one Jovinianus that virginity and marriage were of equal worth", as one of many examples.[11]

As author Ruth Evans notes in her book, "Feminist Readings in Middle English Literature: the Wife of Bath and All her Sect",[12] the Wife of Bath embodies the ideology of "sexual economics," wherein described as the "psychological effects of economic necessity, specifically on sexual mores."[12] The wife is described as a woman in the trade of textiles, she is neither upper-class or lower, strictly a middle-class woman living independently off her own profit. The Wife of Bath sees the economics of marriage as a profitable business endeavor, based solely on supply and demand: she sells her body in marriage and in return is given money in the form of titles and inheritance.[12] She is both the broker and commodity in this arrangement.

The Wife of Bath's first marriage occurred at the age of twelve which highlights the lack of control that women and girls had over their own bodies in medieval Europe as children were often bartered in marriage to increase family status. By choosing her next husbands and subsequently "selling herself," she regains some semblance of control and ownership over her body, and the profit is solely hers to keep.[12]

The simple fact that she is a widow who has remarried more than once radically defies medieval conventions. Further evidence of this can be found through her observation: "For hadde God commanded maydenhede, / Thanne hadde he dampned weddyng with the dede."[13] She refutes Jerome's proposition concerning virginity and marriage by noting that God would have condemned marriage and procreation if He had commanded virginity. Her decision to include God as a defence for her lustful appetites is significant, as it shows how well-read she is. By the same token, her interpretations of Scripture, such as Paul on marriage,[14] are tailored to suit her own purposes.[15]

While Chaucer's Wife of Bath is clearly familiar with the many ancient and medieval views on proper female behavior, she also boldly questions their validity. Her repeated acts of remarriage, for instance, are an example of how she mocks "clerical teaching concerning the remarriage of widows".[16] Furthermore, she adds, "a rich widow was considered to be a match equal to, or more desirable than, a match with a virgin of property",[16] illustrating this point by elaborating at length concerning her ability to remarry four times, and attract a much younger man.

While she gleefully confesses to the many ways in which she falls short of conventional ideals for women, she also points out that it is men who constructed those ideals in the first place.

Who painted the lion, tell me who?

By God, if women had written stories,

As clerks have within their studies,

They would have written of men more wickedness

Than all the male sex could set right.[17]

That does not, however, mean they are not correct, and after her critique she accepts their validity.[6]

Behaviour in marriage

Both Carruthers and Cooper reflect on the way that Chaucer's Wife of Bath does not behave as society dictates in any of her marriages. Through her nonconformity to the expectations of her role as a wife, the audience is shown what proper behaviour in marriage should be like. Carruthers' essay outlines the existence of deportment books, the purpose of which was to teach women how to be model wives. Carruthers notes how the Wife's behaviour in the first of her marriages "is almost everything the deportment-book writers say it should not be."[16] For example, she lies to her old husbands about them getting drunk and saying some regrettable things.[18] Yet, Carruthers does note that the Wife does do a decent job of upholding her husbands' public honour. Moreover, deportment books taught women that "the husband deserves control of the wife because he controls the estate";[19] it is clear that the Wife is the one who controls certain aspects of her husband's behaviour in her various marriages.

Cooper also notes that behaviour in marriage is a theme that emerges in the Wife of Bath's Prologue; neither the Wife nor her husbands conform to any conventional ideals of marriage. Cooper observes that the Wife's fifth husband, in particular, "cannot be taken as any principle of correct Christian marriage".[20] He, too, fails to exhibit behaviour conventionally expected within a marriage. This can perhaps be attributed to his young age and lack of experience in relationships, as he does change at the end, as does the Wife of Bath. Thus, through both the Wife's and her fifth and favorite husband's failure to conform to expected behaviour in marriage, the poem exposes the complexity of the institution of marriage and of relationships more broadly.

Female sovereignty

As Cooper argues, the tension between experience and textual authority is central to the Prologue. The Wife argues for the relevance of her own marital experience. For instance, she notes that:

Unnethe myghte they the statut holde "unnethe" = not easily

In which that they were bounden unto me. "woot" = know

Ye woot wel what I meene of this, pardee! "pardee" = "by God", cf. French "par dieu"

As help me God, I laughe whan I thynke

How pitously a-nyght I made hem swynke! (III.204–08) "hem" = them; "swynke" = work

The Wife of Bath's first three husbands are depicted as subservient men who cater to her sexual appetites. Her characterisation as domineering is particularly evident in the following passage:

Of tribulacion in mariage,

Of which I am expert in al myn age

This is to seyn, myself have been the whippe. (III.179–81)

The image of the whip underlines her dominant role as the partnership; she tells everyone that she is the one in charge in her household, especially in the bedroom, where she appears to have an insatiable thirst for sex; the result is a satirical, lascivious depiction of a woman, but also of feudal power arrangements.

However, the end of both the Prologue and the Tale make evident that it is not dominance that she wishes to gain, in her relation with her husband, but a kind of equality.

In the Prologue she says: "God help me so, I was to him as kinde/ As any wyf from Denmark unto Inde,/ And also trewe, and so was he to me." In her Tale, the old woman tells her husband: "I prey to God that I mot sterven wood,/ But I to yow be also good and trewe/ As evere was wyf, sin that the world was newe."

In both cases, the Wife says so to the husband after she has been given "sovereyntee". She is handed over the control of all the property along with the control of her husband's tongue. The old woman in the Wife of Bath's Tale is also given the freedom to choose which role he wishes her to play in the marriage.

Economics of love

In her essay "The Wife of Bath and the Painting of Lions," Carruthers describes the relationship that existed between love and economics for both medieval men and women. Carruthers notes that it is the independence that the Wife's wealth provides for her that allows her to love freely.[21] This implies that autonomy is an important component in genuine love, and since autonomy can only be achieved through wealth, wealth then becomes the greatest component for true love. Love can, in essence, be bought: Chaucer makes reference to this notion when he has the Wife tell one of her husbands:

Is it for ye wolde have my queynte allone? "queynte" = a nice thing, cf. Latin quoniam, with obvious connotation of "cunt"

Wy, taak it al! Lo, have it every deel! "deel" = "part"; plus, the implication of transaction

Peter! I shrewe yow, but ye love it weel; "Peter" = St. Peter; "shrewe" = curse; hence: "I curse you if you don't love it well."

For if I wolde selle my bele chose, "belle chose": another suggestion of female genitalia (her "lovely thing")

I koude walke as fressh as is a rose;

But I wol kepe it for youre owene tooth. (III.444–49) "tooth" = taste, pleasure

The Wife appears to make reference to prostitution, whereby "love" in the form of sex is a "deal" bought and sold. The character's use of words such as "dette (debt)"[22] and "paiement (payment)"[23] also portray love in economic terms, as did the medieval Church: sex was the debt women owed to the men that they married. Hence, while the point that Carruthers makes is that money is necessary for women to achieve sovereignty in marriage, a look at the text reveals that love is, among other things, an economic concept. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact that her fifth husband gives up wealth in return for love, honour, and respect.

The Wife of Bath does take men seriously and wants them for more than just sexual pleasure and money.[24] When the Wife of Bath states, "but well I know, surely, God expressly instructed us to increase and multiply. I can well understand that noble text"[9] to bear fruit, not in children, but financially through marriage, land, and from inheritance when her husbands die;[25] Chaucer's Wife chose to interpret the meaning of the statement by clarifying that she has no interest in childbearing as a means of showing fruitfulness, but the progression of her financial stability is her ideal way of proving success.

Sex and Lollardy

While sexuality is a dominant theme in The Wife of Bath's Prologue, it is less obvious that her sexual behaviour can be associated with Lollardy. Critics such as Helen Cooper and Carolyn Dinshaw point to the link between sex and Lollardy. Both describe the Wife's knowledge and use of Scripture in her justification of her sexual behaviour. When she states that "God bad us for to wexe and multiplye",[26] she appears to suggest that there is nothing wrong with sexual lust, because God wants humans to procreate. The Wife's "emphatic determination to recuperate sexual activity within a Christian context and on the authority of the Bible [on a number of occasions throughout the text] echoes one of the points made in the Lollard Twelve Conclusions of 1395".[27] The very fact that she remarries after the death of her first husband could be viewed as Chaucer's characterisation of the Wife as a supporter of Lollardy, if not necessarily a Lollard herself, since Lollards advocated the remarriage of widows.[28]

Author Alistair Minnis makes the assertion that the Wife of Bath is not a Lollard at all but was educated by her late husband Jankyn, an Oxford-educated clerk, who translated and read aloud anti-feminist texts.[29] Jankyn gave her knowledge far beyond what was available to women of her status which explains how she can hold her own when justifying her sexual behavior to the Canterbury group. Further, Minnis explains that "being caught in possession of a woman's body, so to speak, was an offense in itself, carrying the penalty of a life-sentence",[29] showing a perception that in medieval Europe, women could not hold priestly duties on the basis of their sex and no matter how flawless her moral status was, her body would always bar her from the ability to preach the word of God. Minnis goes on to say that "it might well be concluded that it was better to be a secret sinner than a woman"[29] as a sinful man could always change his behavior and repent, but a woman could not change her sex.

Femininity

In an effort to assert women's equality with men, the Wife of Bath states that an equal balance of power is needed in a functional society.[1] Wilks proposes that through the sovereignty theme, a reflection of women's integral role in governance compelled Chaucer's audience to associate the Wife's tale with the reign of Anne of Bohemia.[30] By questioning universal assumptions of male dominance, making demands in her own right, conducting negotiations within her marriages and disregarding conventional feminine ideals, Chaucer's Wife of Bath was ahead of her time.

The Queen's Law

The Wife of Bath's Tale reverses the medieval roles of men and women (especially regarding legal power), and it also suggests a theme of feminist coalition-building. Appointed as sovereign and judge over the convicted knight, the Queen holds a type of power given to men in the world outside the tale. She has power as judge over the knight's life.[31] Author Emma Lipton writes that the Queen uses this power to move from a liberal court to an educational court.[32] In this sense the court is moving beyond punishment for the offense, and it now puts a meaning behind the offense, tying it to consequences. In the tale, the Queen is a figurehead for a feminist movement within a society that looks much like the misogynistic world in which the Canterbury Tales are told.[32] From this tale's feminist notion that the Queen leads, women are empowered rather than objectified. The effect of feminist coalition-building can be seen through the knight. As a consequence for the knight's sexual assault against the maiden, when the old woman asks the Queen to allow the knight to marry her, the Queen grants it. This shows support for the broader female community's commitment to education in female values. In response to this fate, the knight begs the court and the Queen to undo his sentence, offering all his wealth and power: "Take all my goods and let my body go,"[33] which the Queen does not allow. The knight's lack of agency in this scene demonstrates a role reversal, according to Carissa Harris, in juxtaposition to women's lack of agency in situations of rape.[34]

Adaptations

Pasolini adapted the prologue of this tale in his film The Canterbury Tales.[35] Laura Betti plays the wife of Bath and Tom Baker plays her fifth husband.

Zadie Smith adapted and updated the prologue and story for the Kiln Theatre in Kilburn in 2019 as The Wife of Willesden, with a running from November 2021 to January 2022.[35]

Karen Brookes has written a book based on the tale: The Good Wife of Bath, as has Chaucer scholar Marion Turner: The Wife of Bath: A Biography.[35]

See also

- Blaesilla, on whom the tale is partly based.

- Bacon in the fabliaux — a figurative use of bacon echoed by Chaucer

References

- "Jonathan Blake. Struggle For Female Equality in 'The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale'". www.luminarium.org.

- The English 'Loathly Lady' Tales: Boundaries, Traditions, Motifs. p. 13.

- Feminist Readings in Middle English Literature: the Wife of Bath and All Her Sect. p. 75.

- Crane, Susan (1 January 1987). "Alison's Incapacity and Poetic Instability in the Wife of Bath's Tale". PMLA. 102 (1): 22. doi:10.2307/462489. JSTOR 462489. S2CID 164134612.

- On Hammond's coining of this term, see Scala, Elizabeth (2009). "The Women in Chaucer's 'Marriage Group'". Medieval Feminist Forum. 45 (1): 50–56. doi:10.17077/1536-8742.1766. Scala cites Hammond, p. 256, in support, and points out that Kittredge himself, in his essay's first footnote, confesses that "The Marriage Group of the 'Canterbury Tales' has been much studied, and with good results" (Scala, p. 54).

- George, Jodi-Anne, Columbia Critical Guides: Geoffrey Chaucer, the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), p. 149.

- Roger, Euan; Sobecki, Sebastian (2022). "Geoffrey Chaucer, Cecily Chaumpaigne, and the Statute of Laborers: New Records and Old Evidence Reconsidered". Chaucer Review. 57 (4): 407–437. doi:10.5325/chaucerrev.57.4.0407. S2CID 252866367.

- "Chaucer the Rapist? Newly Discovered Documents Suggest Not". New York Times. 13 October 2022.

- The Wife of Bath's Tale. p. 28.

- Crane, Susan (1 January 1987). "Alison's Incapacity and Poetic Instability in the Wife of Bath's Tale". PMLA. 102 (1): 20–28. doi:10.2307/462489. JSTOR 462489. S2CID 164134612.

- Cooper 1996: 141.

- Feminist readings in Middle English literature : the Wife of Bath and all her sect. Ruth Evans, Lesley Johnson. London: Routledge. 1994. ISBN 0-203-97679-7. OCLC 61284156.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - III 69–70.

- III. 158–61.

- Cooper 1996: 144.

- Carruthers 1979: 213.

- Benson, Larry D. The Riverside Chaucer. Houghton Mifflin Company. 1987. 692-96.

- III.380–82.

- Carruthers 1979:214)

- Cooper 1996:149.

- Carruthers 1979:216

- III.130.

- III.131.

- The English "Loathly Lady" Tales: Boundaries, Traditions, Motifs. p. 92.

- Feminist Readings in Middle English Literature: the Wife of Bath and All Her Sect. p. 71.

- III.28.

- Cooper 1996:150.

- Cooper 1996:150; Dinshaw 1999:129.

- Minnis, Alistair (2008). Fallible Authors: Chaucer's Pardoner and Wife of Bath. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 246–248. ISBN 978-0-8122-4030-6.

- The English "Loathly Lady" Tales: Boundaries, Traditions, Motifs. p. 73.

- "3.1 The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale". Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer Website. lines 895-898. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Lipton, Emma (2019). "Contracts, Activist Feminism, and the Wife of Bath's Tale". The Chaucer Review. 54 (3): 335–351. doi:10.5325/chaucerrev.54.3.0335. ISSN 0009-2002. S2CID 191742392.

- "3.1 The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale". Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer Website. line 1061.

- Harris, Carissa (2017). "Rape and Justice in the Wife of Bath's Tale". The Open Access Companion to the Canterbury Tales.

- A Wife of Bath 'biography' brings a modern woman out of the Middle Ages (NPR interview with Chaucer scholar Marion Turner, 2023)

Sources

- Blake, Jonathan. "Struggle For Female Equality in 'The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale.'" Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature, 25 September 1994, www.luminarium.org/medlit/jblake.htm. Accessed 23 February 2017.

- Brother Anthony. "Chaucer and Religion." Chaucer and Religion, Sogang University, Seoul, hompi.sogang.ac.kr/anthony/Religion.htm. Accessed 22 February 2017.

- Carruthers, Mary (March 1979). "The Wife of Bath and the Painting of Lions". PMLA. 94 (2): 209–22. doi:10.2307/461886. JSTOR 461886. S2CID 163168704.

- Carter, Susan (2003). "Coupling the Beastly Bride and the Hunter Hunted: What Lies Behind Chaucer's Wife of Bath's Tale". The Chaucer Review. 37 (4): 329–45. doi:10.1353/cr.2003.0010. JSTOR 25096219. S2CID 161200977.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (1987). "The Wife of Bath's Prologue". The Riverside Chaucer (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 105–16. ISBN 978-0395290316.

- Cooper, Helen (1996). "The Wife of Bath's Prologue". Oxford Guides to Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198711551.

- Crane, Susan. "Alyson's Incapacity and Poetic Instability in the Wife of Bath's Tale." PMLA, vol. 102, no. 1, 1987, pp. 20–28., www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/462489.pdf. Accessed 22 February 2017.

- Dinshaw, Carolyn (1999). "Good Vibrations: John/Eleanor, Dame Alys, the Pardoner, and Foucault". Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822323655.

- Evans, Ruth. "Sexual Economics, Chaucer's Wife of Bath." Feminist Readings in Middle English Literature: the Wife of Bath and All Her Sect. Ed. Lesley Johnson and Sheila Delany. Routledge, 2004. 71–85.

- Getty, et al. "The Wife of Bath's Tale." World Literature I: Beginnings to 1650, vol. 2, University of North Georgia Press, Dahlonega, GA, pp. 28–37.

- Green, Richard Firth (2007). ""Allas, Allas! That Evere Love Was Synne!": John Bromyard v. Alice of Bath". The Chaucer Review. 42 (3): 298–311. doi:10.1353/cr.2008.0005. JSTOR 25094403. S2CID 161919144.

- Hammond, Eleanor Prescott (1908). Chaucer: A Bibliographic Manual. New York: Macmillan.

- Kittredge, George Lyman (April 1912). "Chaucer's Discussion of Marriage". Modern Philology. 9 (4): 435–67. doi:10.1086/386872. JSTOR 432643.

- Passmore, Elizabeth S., and Susan Carter. The English "Loathly Lady" Tales: Boundaries, Traditions, Motifs. Medieval Institute Publications, 2007.

- Rigby, S. H. (Stephen Henry) (2000). "The Wife of Bath, Christine de Pizan, and the Medieval Case for Women". The Chaucer Review. 35 (2): 133–65. doi:10.1353/cr.2000.0024. JSTOR 25096124. S2CID 162359113.

External links

- "The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale", middle-english hypertext with glossary and side-by-side middle english and modern english

- Read "The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale" with interlinear translation

- Modern Translation of the Wife of Bath's Tale and Other Resources at eChaucer

- "The Wife of Bath's Tale" – a plain-English retelling for laypeople.

.jpg.webp)